History of Suriname

The history of Suriname encompasses developments in the territory of the Republic of Suriname from prehistory to the present. Its beginnings date back to 3000 BC when the first Indians colonized the area. Today's Suriname was home to many different indigenous cultures. The largest tribes were the Arawak , a nomadic coastal people who lived from hunting and fishing, and the Caribs . The Arawak (Kali'na) were the first inhabitants of Suriname, the Caribs later appeared and subjugated the Arawak by taking advantage of their sailing ships. They settled in Galibi (Kupali Yumï, German "tree of ancestors") at the mouth of the Marowijne River . While the larger Arawak and Carib tribes lived on the coast and in the savannas, there were also smaller groups in the dense tropical rainforest of the hinterland, such as the Akurio, Trió, Wayarekule, Warrau and Wayana.

Early European influences

Christopher Columbus was the first European to discover the coast in 1498, and in 1499 an expedition under the command of Amerigo Vespucci and Alonso de Ojeda explored the coast in more detail. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón explored the interior of the country in 1500. Later, Dutch traders who visited the area on a trip along South America's wild coasts came along and tried to set up a branch first. Further attempts to colonize Suriname by Europeans can be found in 1630, when English settlers under Captain Marshall tried to establish a colony . They cultivated tobacco plants, but the project failed.

In 1651, Lord Francis Willoughby , Governor of Barbados , made the second attempt to establish an English settlement. The expedition was led by Anthony Rowse , who founded a colony and named it 'Willoughbyland'. It consisted of about 500 sugar cane plantations and a fort (Fort Willoughby). The colonists ruined the natural environment and had the forests cut down. Most of the work was done by the 2,000 African slaves who also imported new mosquito plagues from Africa. About 1,000 whites lived there, soon to be joined by other Europeans and Brazilian Jews. On February 27, 1667, during the Second Anglo-Dutch Sea War , the settlement was occupied by Dutch people from Zeeland, led by Abraham Crijnssen . After a short bombardment, Fort Willoughby was captured under Governor William Byam and renamed Fort Zeelandia. Crijnssen guaranteed the settlers of the colony the same rights as under English rule, for example the right to freedom of belief for the Jewish settlers. He appointed Maurits de Rama, one of his captains, governor and left 150 soldiers to protect the newly conquered colony. On July 31, 1667, the Peace of Breda was concluded, which, in addition to the terms of peace, awarded Guyana to the Dutch and New Amsterdam (now New York City ) to the English . Willoughbyland was subsequently renamed Dutch Guiana; this arrangement became official with the Treaty of Westminster in 1674, after the British retook and lost Suriname in 1667 and the Dutch occupied New Amsterdam again in 1673. The Dutch multiplied the number of slaves and treated them even worse than the English before them.

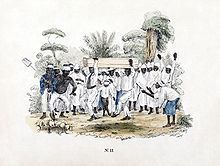

Agriculture flourished in Suriname in the first half of the 18th century, with the main crops being coffee, cocoa, tobacco, sugar and indigo. Most of the work on the plantations was done by around 60,000 African slaves, mainly from the present-day states of Ghana, Benin, Angola and Togo, who were mostly badly treated; many slaves therefore fled into the jungle, where they formed communities that were or are organized like tribes. These Maroons (also known as Bosnegers in Suriname ) often returned to the colonized areas to raid plantations. Famous leaders of the Maroons from Suriname were Alabi, Boni and Broos (Captain Broos). They formed a kind of buffer between the Europeans who settled on the coast and the main rivers, and the indigenous peoples of the hinterland, who were not yet subjugated. A contemporary description of this situation in Suriname can be found in John Gabriel Stedman's story of a five-year punitive expedition against insurgent blacks. On October 10, 1760, the colonial administration signed a first peace treaty with escaped slaves from the Ndyuka tribe . Since 2011, October 10th has been a national holiday as Dag der Marrons (Maroons Day). The Maroons have contributed greatly to the abolition of slavery.

After France annexed the Netherlands in 1799, Guyana was reoccupied by the British. At the Congress of Vienna in 1815 it was decided that the English would keep what is now Guyana and give Suriname back to the Dutch.

abolition of slavery

The Dutch were the last European nation to abolish slavery until 1863. In any case, the slaves were not released until 1873; until then they did paid but compulsory work on the plantations (the period of the so-called ten-year state duty ). Meanwhile, many contract workers had come from Asia, mainly Chinese. After 1873, many Hindus were brought to Suriname from India as workers ; however, this emigration was ended in 1916 by Mohandas Gandhi . From that year many people came from the Dutch East Indies , especially from Java ; Immigrants from China also came to Dutch Guiana more or less regularly. Suriname developed into a multi-ethnic state in which Creoles (37%) and people of Indian (around 35%), Indonesian (14%) and Chinese origin lived together.

Suriname's natural resources such as rubber , gold and bauxite were discovered even before the First World War . In 1916, the US company Alcoa acquired the rights to a large area south of the capital where bauxite was found. During the Second World War , the Dutch colony was occupied by the United States on November 25, 1941, in agreement with the Dutch government-in-exile . a. to protect the bauxite mines.

On December 9, 1948, universal suffrage was introduced; women were also eligible to vote. The number of MPs increased to 21.

Independence

In 1954, Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles gained limited self-government through the Kingdom Statute; the Dutch, however, carried on defense and foreign affairs themselves.

In 1973 the local administration, led by the great Creole-Javanese coalition (between NPS and KTPI), started negotiations on full independence, which came into force on November 25, 1975. With independence in 1975 the active and passive right to vote was confirmed.

The Dutch set up a $ 1.5 billion aid program that would run through 1985. The first president of the young state was Johan Ferrier , the previous governor, and Henck AE Arron , the leader of the NPS (National Party of Suriname), became prime minister. About a third of the population emigrated to the Netherlands, fearing that the small state would not be able to survive. Many of the emigrants were wealthy Indians who feared that if the Creoles came to power, an economic decline would set in, which actually did later.

The military coup

On February 25, 1980, the Creole-dominated government of Henck Arron was overthrown on suspicion of corruption in a military coup led by Sergeant Desi Bouterse , also known as the Sergeant Coup . President Ferrier refused to recognize the new rulers, namely the National Military Council (NMR) led by Sergeant Badrissein Sital. Other members of the NMR were Bouterse (on the way to the commander), Oberfeldwebel Roy Horb , Feldwebel Laurens Neede, Lieutenant Michel van Rey (the only one with officer training) and three other NCOs. The elections, which were scheduled for March 27, 1980, were canceled and, surprisingly, the politically largely inactive doctor Hendrick Chin A Sen was appointed Prime Minister. After three council members, namely Chairman Badrissein Sital, Chas Mijnals and Stanley Joeman, were disarmed and arrested on Bouterses initiative on charges of planning a counter-coup, a state of emergency was declared on August 13, 1980, and the constitution was suspended the parliament dissolved. President Ferrier, who had been in power since 1975, was ousted by the military , which then fell to Chin A Sen. Another coup later followed in which the army replaced Ferrier with Chin A Sen. The Militair-Gezag (military command), consisting of Bouterse and Horb, officially entered the innermost circle of power. On February 4, 1982 Chin A Sen resigned because of differences with the NMR about the economic and political course, he was replaced by the lawyer and politician Ramdat Misier . These developments were largely welcomed by the population, who expected the new army-backed government to put an end to corruption and raise living standards - even though the government outlawed opposition parties and became increasingly dictatorial over time. The Dutch accepted the new government at the beginning, but relations between Suriname and the Netherlands collapsed when the army shot and killed 15 opposition members on December 8, 1982 in Fort Zeelandia without any form of trial. These events are also known as the " December murders " ( Decembermoorden in Dutch). The Dutch and Americans interrupted their aid deliveries in protest, which resulted in Bouterse looking for help from countries such as Grenada , Nicaragua , Cuba and Libya .

On November 25, 1985, the tenth anniversary of independence, the ban on opposition parties was lifted and a new constitution began. However, this process was severely hampered the following year when a kind of guerrilla war between the Maroons and the government began. The guerrillas from the interior called themselves Jungle Commando and were led by Ronnie Brunswijk , a former bodyguard of Bouterses. The government troops under Bouterse tried to suppress the riot by force by setting fire to villages, as happened on November 29, 1986 in Moiwana , when the Brunswijks house was burned down and at least 35 people were killed, mostly women and children. Many Maroons fled to French Guiana . The war was generally very brutal, for example the city of Albina was almost completely destroyed; a total of almost 1,000 people died.

According to Ronald Reagan's diaries ( The Reagan Diaries ) published in May 2007 , the Dutch government investigated a military intervention in Suriname in 1986 after the Moiwana massacre . The Hague wanted to overthrow Desi Bouterse's military regime. To this end, The Hague sent a request for help to the United States for the transport of 700 Dutch soldiers from Corps Mariniers . The US considered the request for assistance, but before a decision was made, the Dutch government withdrew its request.

The 1990s

In November 1987, following the introduction of the new constitution, elections were held, in which the three-party anti-Bouterse coalition Front for Democracy and Development won 40 out of 51 seats; Dutch aid resumed the following year. Soon, however, tensions developed between Bouterse and President Ramsewak Shankar . As a result, Shankar was ousted on December 24, 1990 in a coup known as the telephone coup led by Bouterse. A military-backed regime was installed; Johan Kraag was installed as president by the NPS.

Elections were held again on May 25, 1991. Ronald Venetiaan's Nieuw Front, a new coalition (the three coalition parties of the old front combined with the Surinamese Labor Party) won 30 seats, Bouterses NDP won 12 and the Democratisch Alternatief '91 (a multi-ethnic party advocating closer ties with the Netherlands ) won their 9. 30 seats were not enough to provide the president; so a parliamentary election was organized, which was won by Venetiaan. In August 1992 a treaty signed with the Jungle Commando brought peace, in the same year the NMR was dissolved.

Meanwhile, the Suriname economy faced serious difficulties, due to a fall in world aluminum prices, acts of sabotage by rebels, the end of development aid and large deficits. A program for adapting the structures (SAP) was started in 1992, followed by the multi-year development program from 1994. Despite import restrictions, the situation did not improve noticeably. This fact and a series of corruption scandals resulted in a marked downturn in the popularity of Venetiaan's New Front.

Nevertheless, the Nieuw Front won the elections held on May 23, 1996, albeit with a small majority. As in 1991, that was not enough to make Venetiaan president. Many members of the Nieuw Front switched to the NDP and other parties. The secret election that followed secured the presidency for Jules Wijdenbosch , a former vice-president in the Bouterse era who set about forging a coalition of the NDP and five other parties. Bouterse was housed in 1997 when the post of State Chancellor was created for him. Nevertheless, Wijdenbosch released him in April 1999. Meanwhile, the Dutch judiciary sentenced Bouterse in absentia to several years in prison for illegal drug trafficking. His son, Dino Bouterse, was convicted in 2005 on a similar charge.

From 2000

Because of the government's failure to improve economic problems, widespread strikes broke out in 1999, during which the strikers demanded early elections. This resulted in the collapse of Wijdenbosch's coalition, and he lost a vote of confidence in June 1999. The elections, scheduled for 2001, were brought forward to May 25, 2000. Support for Wijdenbosch fell to 9% of the vote, Venetiaan won 47%. Relations with the Netherlands improved when Venetiaan took office. Meanwhile, relations between Suriname and Guyana deteriorated over a dispute over the countries' maritime borders. It is believed that the area could be rich in oil.

In August 2001 the Dutch enabled Suriname to take out a ten-year loan of 137.7 million euros from the Dutch Development Bank (NTO). US $ 32 million of the loan was used to pay off foreign loans that were taken out under unfavorable conditions during the Wijdenbosch tenure. The remaining 93 million was used to repay debt to the Central Bank of Suriname. This in turn enabled it to strengthen its international position. To help the economy even further, the guilder was replaced by the Surinamese dollar in 2004.

In the elections in May 2005, Venetiaan won again. However, in the 2010 elections, when Desi Bouterse was elected the new President of Suriname by parliament on July 19, it became clear that some of the old military still have an impact on the country's politics and everyday life. The non-profit, non-governmental organization Center for a Secure Free Society (SFS) called Suriname a “criminal state” in a report published in March 2017.

The main parties of Suriname

| Name (abbreviation) | Political Direction | founding |

|---|---|---|

| National Party of Suriname (NPS) | creole democrats | 1946 |

| Hardly Tani Persatuan Indonesia (KTPI) | Indonesian Democrats | 1947 |

| Verenigde Hervormings Partij (VHP) | left-wing Indians | 1949 |

| Partij Nationalist Republiek (PNR) | nationalist | 1963 |

| National Democratic Party (NDP) | national democratic | 1987 |

| Nieuw Front (NF) | left-wing democratic | 1987 |

| Democratic Alternative '91 (DA '91) | social democratic | 1991 |

| Basispartij Voor Vernieuwing en Democratie (BVD) | grassroots democracy | k. A. |

See also

- List of governors of Suriname

- List of presidents of Suriname

- List of Prime Ministers of Suriname

- Dutch colonies

literature

- About the decline of Suriname and the plan to found a free European colonization there . In: Illustrirte Zeitung . No. 23 . J. J. Weber, Leipzig December 2, 1843, p. 358 ( books.google.de ).

- Eveline Bakker et al .: Geschiedenis van Suriname. Van stam dead state . De Walburg Pers, Zutphen 1993. ISBN 90-6011-837-5 .

- Conrad Friederich Albert Bruijning, Jan Voorhoeve (ed.): Encyclopedie van Suriname . Elsevier, Amsterdam and Brussels 1977. ISBN 90-10-01842-3 .

- Hans Buddingh ': Geschiedenis van Suriname. A full overzicht van de oorspronkelijke, Indiaanse bewoners en de ontdekking door Europese colonists, tot de opkomst van de drugbaronnen . Het Spectrum, Utrecht 2000. ISBN 90-274-6762-5 .

- Hans Buddingh ': De Geschiedenis van Suriname . Nieuw Amsterdam / NRC Boeken, Amsterdam 2012. ISBN 978-90-468-1103-0

- Bernhard Conrad (Ed.): Between Ariane, Merian and Papillon: Stories from French Guiana and Suriname . BoD, Norderstedt 2015. ISBN 978-373-4-79814-6 (Part II, Suriname pp. 141–199: on Civil War pp. 143–154; on Maroons pp. 181–190)

- Bernhard Conrad: Suriname. With Paramaribo World Heritage Site . BoD, Norderstedt 2019. ISBN 978-3-749-42881-6 (on history pp. 38–58; on Anna Maria Sibylla Merian pp. 31–37; on Herrnhuter pp. 105-108; on politics pp. 68–78 ; on population and ethnic groups, pp. 79–98)

- Jos Fontaine: Zeelandia. De divorced van een gone . De Walburg Pers, Zutphen 1972. ISBN 90-6011-441-8 .

- Cornelis Christiaan Goslinga: A short history of the Netherlands Antilles and Surinam . Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague 1979. ISBN 90-247-2118-0 .

- Rosemarijn Hoefte, Peter Meel (Ed.): Twentieth Century Suriname. Continuities and Discontinuities in a New World Society . KITLV Press, Leiden 2001. ISBN 90-6718-181-1 .

- Wim Hoogbergen: De oorlog van de sergeanten. Surinaamse militairen in de politiek . Uitg. Bert Bakker, Amsterdam 2005.

- Rudie Kagie: Een gewezen wingewest. Suriname voor en na de stategreep . Het Wereldvenster, Bussum 1980.

- Gerard Willem van der Meiden: Betwist bestuur. Een eeuw strijd om de macht in Suriname 1651-1753 . De Bataafsche Leeuw, Amsterdam 1987. ISBN 90-6707-133-1 .

- Matthew Parker: Willoughbyland - England's Lost Colony . Hutchinson, London 2015.

- Jules Sedney: De toekomst van ons verleden. Democratie, etniciteit en politieke Machtsvorming in Suriname . VACO NV, Paramaribo 1997 [3. Edition 2017, completely revised and supplemented; Uitg. VACO].

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Robin Lane Fox : Vision of hell , Matthew Parker (2015), in: Financial Times , November 28, 2015, p. 18

- ↑ Omhoog (Paramaribo), Vol. 62, No. 39, October 22, 2017.

- ↑ Kerstin Hartmann: Surinam during the Second World War . In: Freddy Dutz, Martin Keiper (Ed.): Surinam. Land of many peoples and religions . Evangelical Mission in Germany (EMW). Hamburg 2017, ISBN 978-3-946352-07-5 , pp. 31–43, here p. 34.

- ^ Felix Gallé: Surinam. In: Dieter Nohlen (Ed.): Handbook of the election data of Latin America and the Caribbean (= political organization and representation in America. Volume 1). Leske + Budrich, Opladen 1993, ISBN 3-8100-1028-6 , pp. 703-717, p. 706.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 362.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. December 9, 1948, accessed October 6, 2018 .

- ↑ / Article in Caribbean News

- ↑ Bouterse spreekt na jaren met Venetiaan ( Memento of the original from July 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , In: NRC Handelsblad , July 29, 2010, (ndl.)

- ↑ Suriname ex-strongman Bouterse back in power , In: BBC News , July 19, 2010, (English)

- ↑ Secure Free Society: Suriname: The New Paradigm of a Criminalized State , March 2017 English, accessed on March 18, 2017