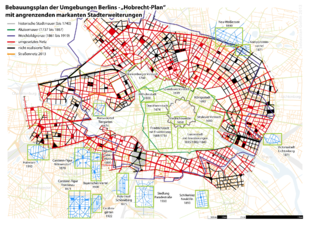

Hobrecht plan

The Hobrecht Plan is the usual name for the development plan for the surroundings of Berlin, named after its main author James Hobrecht and which came into force in 1862 . As an alignment plan, this should regulate the routing of ring roads and arterial roads and the development of the cities of Berlin , Charlottenburg and five surrounding communities for the next 50 years.

initial situation

In the course of industrialization there was also a rural exodus in Germany . Attracted by better earning opportunities and a larger supply of jobs, the population of Berlin rose from 172,122 (1800) to 774,452 (1872) to 1,902,509 in 1919.

As the population increased, so did the hygienic conditions, the supply of the population and, above all, the living conditions. The mostly narrow streets and alleys in the city center were hardly able to cope with the volume of traffic. A rapidly growing industry contributed to air pollution . The population growth led to the move to the suburbs. The infrastructure had to be developed. Railway stations, wider streets, a well-developed transport network and the creation of technical and hygienic requirements were necessary. In addition, the swamping of large areas, for example in Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf, prevented development for residential purposes and the paving of roads. The development of a sewer system to discharge the wastewater and the supply of clean water, while at the same time improving the road system to the surrounding area, had to be undertaken.

Based on the population growth to 1.5 to 2 million inhabitants (1861: 524,900 inhabitants) and the associated traffic and administrative development, uniform urban administration and planning had become necessary.

Planning specifications

The improvement of urban conditions became inevitable as the city grew. Planning for technical and hygienic measures and, above all, an adaptation of the transport infrastructure were necessary.

On behalf of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior, a planning commission of the Royal Police Headquarters was to create plans from 1858 that would do justice to the expected situation. The police were responsible for this, at that time as construction police, also for city and infrastructure planning and important construction tasks. The chairman of the commission was the young government builder James Hobrecht, the younger brother of the Reichstag member and later mayor of the city Arthur Johnson Hobrecht .

The planning was to widen the streets in the city center and connect them to an efficient road network. In accordance with this, the prerequisites for a sewer system and supply lines had to be created. Areas should also be provided for the rapidly growing railway lines and stations. According to the king's wishes, the city area was to be bordered by a boulevard and a number of radial and arterial streets were to be laid out in between. The king had the Paris street plans of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann as a model . In contrast to this plan, in Berlin, as far as possible, no radical breakthroughs in streets should destroy the historically grown city quarters. A ruthless recourse to private land was not legally possible; all land used had to be acquired by the state.

After mapping the current situation, existing plans should be viewed and incorporated into the later planning. These included the proposals for urban planning by Karl Friedrich Schinkel , the development plans by Johann Carl Ludwig Schmid from 1825 and 1830 and, in particular, the urban development plans by Peter Joseph Lenné , who had mainly worked as a garden and landscape architect. In 1840, Lenné was one of the first to draw up an overall plan for Berlin and the surrounding area: Projected decorative and border trains from Berlin to the immediate vicinity . Many of Lenné's ideas and ideas flowed into the Hobrecht Plan. One of the most important elements was the general train planned by Schmid , a sequence of streets and squares that today serve as an east-west connection from Südstern in Kreuzberg to Breitscheidplatz in Charlottenburg . In the area of the later Gleisdreieck area , due to the rapidly increasing expansion of the railway systems, after the original Hobrecht plan had been determined, a plan change with a southward shift was necessary, which formed the basis for the Yorck bridges built here .

The Hobrecht Plan

Due to the growth of the city and the incorporation that took place in 1861, the plans of the Hobrecht Commission extended far beyond the then urban area. The Hobrecht Plan, approved on July 18, 1862 as a development plan for the surroundings of Berlin , comprised the built-up and mapped undeveloped land of the cities of Berlin and Charlottenburg as well as the communities of Reinickendorf , Weißensee , Lichtenberg , Rixdorf and Wilmersdorf in 14 sections .

The plan provided for two ring-shaped belt roads that completely surround the cities of Berlin and Charlottenburg. The still undeveloped areas in between were to be divided into right-angled building blocks by diagonal streets and arterial roads leading in all directions. Bourgeois houses were to be built facing the street; living space for workers and workshops was provided in the inner courtyards. Hobrecht expected that this would allow different strata of the population to live together peacefully.

The Hobrecht plan itself only laid down the course of the streets and their boundaries, it is a pure alignment plan . It did not contain any further regulations on the development of the blocks (for example on the use of the land and the type of use). According to the legal situation at the time, that was not possible either. Only in connection with the building police regulations issued in 1853 did he favor the creation of the Wilhelmine tenement belt . The building police regulations only stipulated within the rather large blocks that the development could have a maximum of six full floors with an eaves height of 20 meters. Courtyards had to have a minimum area of 5.34 meters square for the fire engine to turn.

consequences

Since the building was not regulated by any further regulations, a very dense development emerged in the following years. The lack of further regulations led to real estate speculation and the growth of the notorious tenements of the 'Steinerne Berlin', in which people lived in extremely cramped conditions. Back and side houses were built in the inner area of the blocks , leaving only the required minimum courtyard areas undeveloped. The apartments, which were only sparsely lit by the narrow courtyards, and the hygienic conditions, which were drastically tightened due to the narrow space and the high number of residents, repeatedly led to illnesses. Only with the introduction of the Berlin sewer system with the 12 radial systems and the Berlin sewage fields by 1893 did the situation improve.

Hobrecht, as the author of the plan, is often seen as the main culprit for the development of the tenements and the poor housing conditions there. Only now is the importance of the Hobrecht Plan for urban development recognized. The real responsibility for the emergence of the dense block development was borne by the speculation with real estate and the legislature, which at that time hardly performed its control function for the development. The cause of the tenement problem is not the planning, but the striving to achieve a high profit with as little financial investment as possible. Despite the negative effects, the Hobrecht Plan was a prerequisite for solving the housing problem that arose at the turn of the century and made it possible to introduce urban drainage, which was essential for urban hygiene . His planning is still decisive today for large parts of the Berlin cityscape.

Social intentions, critical evaluation

James Hobrecht spoke of conscious social mix of residents in front and rear buildings, basement, roof and main floor -Apartments a social action to:

“In the tenement , the children go from the basement apartments to the free school via the same hallway as those of the councilor or the merchant, on the way to the grammar school . Shoemaker Wilhelm from the attic and the old, bedridden Frau Schulz in the rear building, whose daughter makes a meager living by sewing or cleaning work, become well-known personalities on the first floor. Here is a bowl of soup to strengthen yourself in the event of illness, there is an item of clothing, there is an effective aid to obtain free instruction or the like and everything that turns out to be the result of the cozy relationships between the similar and even if very differently situated residents Help which exerts its ennobling influence on the giver. And between these extreme social classes move the poor from the 2nd or 4th floor, social classes of the highest importance for our cultural life, civil servants, artists, scholars, teachers etc., and have a supportive, stimulating and thus for society useful. And would it be almost only through their existence and mute example to those who live next to them and mixed with them. "

The left-liberal urban planner, architecture critic and publicist Werner Hegemann , in retrospect, condemned the Hobrecht Plan in 1930 as a project that ...

"[...] officially furnished unpredictable green areas around Berlin for the construction of large, densely packed tenements, each with two to six poorly lit backyards, and condemned four million future Berliners to live in dwellings that neither the dumbest devil nor the most industrious Berlin privy councilor would or do Soil speculator could think of worse. "

literature

- Johann Friedrich Geist , Klaus Kürvers : The Berlin apartment building. Three volumes. Prestel, Munich 1980–1989.

- Klaus Strohmeyer: James Hobrecht. (1825–1902) and the modernization of the city. Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg 2000, ISBN 3-9329-8167-7 .

- Claus Bernet : The Hobrecht Plan (1862). In: Urban History 31, 2004, pp. 400-419.

- Werner Hegemann : The stone Berlin. History of the largest tenement city in the world. Bauwelt Fundamente, Berlin 1930. New edition, abridged, 4th edition, 1988, ISBN 978-3-7643-6355-0 .

- Gabi Dolff-Bonekämper et al. (Ed.): The Hobrechtsche Berlin. Growth, change and value of the Berlin urban expansion , Berlin: DOM publishers 2018 ISBN 978-3-86922-529-6 .

Web links

- Scheme of the Hobrecht plan, overlaid by a map from around 1980 Historical maps → Hobrecht plan 1862 (State Archives and Senate Department for Urban Development)

- That was the plan . In: the daily newspaper , July 31, 2012

Individual evidence

- ^ Werner Hegemann: The stone Berlin , Ullstein Berlin Frankfurt / M Vienna, 1930.