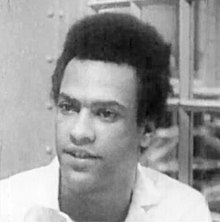

Huey Newton

Huey Percy Newton (born February 17, 1942 in Monroe , Louisiana , † August 22, 1989 in Oakland , California ) was next to Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver one of the three founding members of the Black Panther Party .

Life

Huey Newton was born on February 17, 1942 in Monroe, Louisiana. He was the youngest of seven children. His father, who named his son after the radical politician Huey P. Long , was an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

His family moved to Oakland , California in 1945 because of supposedly better job opportunities . There the family had to move frequently and lived close to the poverty line. Even if Newton sometimes even had to sleep in the kitchen, he never complained about the circumstances and later stated that despite everything he never went hungry.

Huey Newton began studying at Merritt College, but later moved to Oakland City College and San Francisco Law School, where he studied law. During this time, he financed his studies and basic services through burglaries in Oakland and Beverly Hills. For a few more years he acted in an ambivalent relationship between ascribed crime and political activism, since political activism was often equated with delinquent behavior, especially in the mirror of the racist laws of this era.

During his time at Oakland City School, he began to be more interested and involved in politics. He became an active member of the Afro American Association and read the works of Frantz Fanon , Malcolm X , Mao Zedong, and Che Guevara . Here he also met the African American Bobby Seale , who pursued the same political goals as himself. Together with Seale he participated in 1965 in Merritt in the organization of one of the first university seminars on Black Studies , which took place at a non- HBCU .

Seale and Newton became friends and began to coordinate their political work for the civil rights movement. They got involved in the neighborhood, gave speeches on street corners and in cafes, and tried to convince the African American community that it was necessary to take action if they did not want to be further discriminated and disadvantaged. From these beginnings the idea of founding a party soon developed. In 1966 they founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP), with Bobby Seale as party chairman and Huey Newton as defense minister . In terms of content, the BPP was oriented towards socialist social and economic policy ideas.

Newton and Seale decided to put an end to the violence by the Oakland Police against blacks. Through his studies, Newton was very familiar with the gun laws of California and knew that every US citizen was permitted to carry guns in public as long as they were visibly carried. The Black Panthers began to arm themselves and set up patrols to monitor the police and protect their "brothers" from further assault.

In addition to patrols, Seal and Newton wrote the Black Panther Party's 10-point program, which was heavily shaped by Newton's Maoist influence. (see Black Panther Party )

With the rise of the Black Panther Party in the media, both nationally and internationally, the FBI began to see it as a serious threat to the state. The FBI began using four types of intelligence (infiltration, psychological terror, repression and violence) - the name of the program was COINTELPRO - to crack down on the Black Panthers. The Panthers' militant demeanor turned against them. Newton was sentenced to 15 years in prison for the murder of an Oakland police officer in 1968. At the beginning of his detention, he was required to submit a list of ten people or less, and they would be the only ones allowed to visit him. After 22 months of detention ( solitary confinement ) in the Men's Colony in San Luis Obispo , California , the charges were dropped in a retrial.

Newton visited China in 1971, where he met Prime Minister Zhou Enlai and Jiang Qing , Mao Zedong's wife, who offered him political asylum. In 1973, Huey Newton published his autobiography, militantly titled Revolutionary Suicide .

The US police again brought charges against Newton in 1974, including the murder of Kathleen Smith, a 17-year-old prostitute. Newton didn't show up for the trial. His bail was forfeited, a new warrant was issued, and Newton found himself on the FBI's Most Wanted (Criminal) list. He fled to Cuba , where he spent three years in exile. He returned to the United States in 1977 to face the charges. He said the climate in the United States has improved and that he believes that we can get a fair trial. He was acquitted on all charges.

In 1980 he successfully completed a Ph.D. in history from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a dissertation on: War Against the Panthers: A Study of Repression in America .

But Newton began to drink heavily and use drugs. On August 22, 1989, Newton was hit by three bullets from the 9-millimeter pistol of 24-year-old drug dealer Tyrone Robinson, a member of the Black Guerrilla Family , in West Oakland and died the same day.

additional

The memory of Newton was kept alive by numerous black musicians, for example in: Changes by Tupac Shakur , Welcome to the Terrordome by Public Enemy , Queens Get the Money by Nas , Sunny Kim by Andre Nickatina , Just a Celebrity by The Jacka , Same Thing by Flobots , Dreams , Gangbangin '101 , Murder and 911 Is a Joke (Cop Killa) by The Game , You Can't Murder Me by Papoose , Police State , Propaganda , We Want Freedom , Malcolm, Garvey, Huey by Dead Prez . In 1996 the play A Huey P. Newton Story by Roger Guenveur Smith was performed. In 2001 Spike Lee filmed the one-person play.

Works (selection)

- To Die for the People: The Writings of Huey P. Newton . Random House, New York 1972, ISBN 0-394-48085-6 .

- Revolutionary Suicide . Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York 1973, ISBN 0-15-177092-1 . Reprint: Penguin Classics, 2009. ISBN 978-0-14-310532-9 (print); ISBN 978-1-101-14047-5 (eBook)

- Insights and Poems . City Lights Books, San Francisco 1975, ISBN 0-87286-079-5 .

- War Against the Panthers: A Study of Repression in America . Black Classic Press, 1996, ISBN 0-86316-246-0 (Newton's dissertation).

- Black Panther Party (Ed.): Essays from the Minister of Defense . Oakland 1968 ( online version [PDF; 972 kB ] pamphlet).

- The Genius of Huey P. Newton . Awesome Records, 1993, ISBN 1-56411-067-2 ( online version [PDF; 9.1 MB ] reprint).

- Black Panther Party (Ed.): The original vision of the Black Panther Party . 1973.

- Huey Newton talks to the movement about the Black Panther Party, cultural nationalism, SNCC, liberals and white revolutionaries . Alexander Street Press, San Francisco 1968.

- David Hilliard (Ed.): The Huey P. Newton Reader . Seven Stories Press, New York 2002, ISBN 1-58322-466-1 (collection of various Newtonian writings).

- Self defense . Verl. Roter Stern, Frankfurt / M. 1971 (American English: On Self Defense .).

literature

- Elaine Brown: A Taste of Power: A Black Woman's Story . Anchor Books, 1994, ISBN 0-385-47107-6 .

- Philip S. Foner (Editor): The Black Panthers Speak - The Manifesto of the Party: The First Complete Documentary Record of the Panther's Program . Lippincott, 1970.

- David Hilliard: Huey: Spirit of the Panther . Thunder's Mouth Press, New York 2006.

- Judson L. Jeffries: Huey P. Newton, The Radical Theorist . University of Mississippi Press, Oxford (Mississippi) 2002, ISBN 1-57806-432-5 .

- Hugh Pearson: Shadow of the Panther: Huey P. Newton and the Price of Black Power in America . Addison-Wesley, Boston, Massachusetts 1994, ISBN 0-201-48341-6 .

- Bobby Seale: Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton . Random House, New York 1970.

- Huey Newton Symbolized the Rising Black Anger of a Generation , obituary in the New York Times , Dennis Hevesi, 23 August 1989.

Web links

- Literature by and about Huey Newton in the catalog of the German National Library

- Interview with Newton, 1968

Individual evidence

- ↑ According to his own statement in Revolutionary Suicide , New York, Ballantine Books 1974, p. 11.

- ↑ Suspect Admits Shooting Newton, Police Say , The New York Times (August 27, 1989), accessed October 17, 2011

- ↑ Errol A. Henderson: The Lumpenproletariat as Vanguard ?: The Black Panther Party, Social Transformation, and Pearson's Analysis of Huey Newton, pp. 171–199, in: Journal of Black Studies , Volume 28, No. 2 (November 1997 ), P. 175f

- ↑ Ibram H. Rogers: The Black Campus Movement - and the Institutionalization of Black Studies, 1965-1970, in: Journal of African American Studies March 2011 ( doi: 10.1007 / s12111-011-9173-2 )

- ↑ Jessica C. Harris: Revolutionary Black Nationalism: The Black Panther Party, pp. 409-421, in: The Journal of Negro History , Volume 86, No. 3 (Summer 2001), p. 411

- Jump up ↑ J. Herman Blake: The Caged Panther: the Prison Years of Huey P. Newton, in: Journal of African American Studies August 2011 ( doi: 10.1007 / s12111-011-9190-1 )

- ↑ See Huey P. Newton: War Against The Panthers: A Study Of Repression In America, UC Santa Cruz 1980

- ^ "Finally, there's the third bullet. The coup de grace to the back of the head. A sign of a professional making sure Huey was dead. ” According to David Hillard and Lewis Cole: This Side of Glory

- ^ New York Times : Suspect Admits Shooting Newton, Police Say , August 27, 1989, Retrieved May 8, 2013

- ↑ Jama Lazerow, Yohuru R. Williams: In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement . Duke University Press , Duke University 2006, ISBN 0-8223-3890-4 , p. 9.

- ^ Awards for A Huey P. Newton Story . Internet Movie Database. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Newton, Huey |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Newton, Huey P. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American founder of the Black Panther Party |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 17, 1942 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Monroe (Louisiana) |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 22, 1989 |

| Place of death | Oakland , California |