Japanese aesthetic

Japanese aesthetics refers to the principles and aesthetic theories that underlie Japanese art .

General

Two characteristics characterize the aesthetic tradition of Japan. On the one hand, this is the Buddhist belief in the impermanence of being ( 無常 , Mujō ), and on the other hand, Japanese aesthetics is determined by Confucianist self-cultivation, as practiced in the so-called path arts ( 茶道 Chadō , 書 道 Shodō , 弓 道 Kyūdō and others).

An aesthetic theory ( 美学 Bigaku ) in the sense of a philosophical tradition can only be spoken of since the Meiji Restoration , since the theoretical tools for reflexive self-understanding about one's own tradition were only available with the introduction of the Western humanities . Like modern Japanese philosophy, Japanese aesthetic theory is also characterized by a “double difference”: on the one hand, there is a difference compared to western concepts and theories that have been accepted, on the other hand, there is a difference between tradition and modernity in Japan itself.

Terms

Classic ideals

Mono no aware and Okashi

“The pathos of things” or “the heartbreaking of things” ( 物 の 哀 れ , mono no aware ) describes that feeling of sadness that lingers on the transience of things and yet comes to terms with it. As compassion for all things and their inevitable end, mono no aware is an aesthetic principle that primarily describes a feeling, a mood. This attitude is hinted at in one of the earliest literary works, in the collection of ten thousand sheets ( 万 葉 集 , Man'yōshū ). The scholar Motoori Norinaga sees it as exemplified in the literary classic of the story of Prince Genji (approx. 978 – approx. 1014). According to Norinaga, the mono no aware is also a movement of poetry: man begins to write poetry when he “can no longer endure the mono no aware”.

The Okashi ( を か し ) principle, which is also decisive for the Heian period, stands in contrast to the feeling of sadness . As an aesthetic principle, it speaks more to the intellect and describes "cheerfulness", "everything that makes the face smile or laugh." Both principles are above all in court literature ( 王朝 文学 , Ochō Bungaku ). Linhart sees the pillow book by Sei Shōnagon as an exemplary counterpart to the “Story of Prince Genji” and as an example of the inherent principle of Okashi . In the Muromachi period , the quality of cheerfulness to "funny-funny" intensified. Zeami Motokiyo therefore assigned the principle of Okashi to the Kyōgen , the joking interlude, in the otherwise serious Nōgaku theater . The principle can be found again in the "joke books" ( Kokkeibon ) of the Edo period.

In the 20th century, Ozu Yasujirō in particular tried to capture this feeling of mono no aware in his films. The cherry blossom festival ( 花 見 , hanami ), which celebrates the fast-perishing but graceful blossoming of the Japanese cherry trees ( 桜 , sakura ), can still be found in folk culture today .

Wabi-sabi

The difficult to translate Wabi-Sabi ( 侘 寂 ) describes an aesthetic of the imperfect, which is characterized by asymmetry, roughness, irregularity, simplicity and thriftiness. Unpretentiousness and modesty show respect for the uniqueness of things. In comparison with the occidental tradition, it is as important as the western concept of the beautiful .

Wabi can be translated as “tasteful simplicity” or as “modesty bordering on poverty”. Originally it referred to a lonely and secluded life in nature. Sabi originally meant cool, emaciated, withered. Since the 14th century, both terms had increasingly positive connotations and came into use as aesthetic judgments. The hermit's social isolation stood for spiritual wealth and a life that kept an eye out for the beauty of simple things and nature. In terms of content, both terms have converged so closely over the course of time that nowadays it is hardly possible to make a meaningful distinction: Whoever says Wabi also means Sabi and vice versa.

At most, heuristically , a distinction could be made between Wabi as the imperfect, as is involved in the production of an object, and Sabi as those traces of age that shape the object over time. Examples of the latter are patina , worn or uncovered repairs. Etymologically, an attempt was made to trace Sabi back to the Japanese word for rust , even if the Chinese characters differ, or to understand it as the “flower of time”. Such aging processes can be seen very clearly in Hagi ceramics ( 萩 焼 Hagi-yaki ).

The writer and Zen monk Yoshida Kenkō (1283-1350) underlined the importance of Wabi-Sabi for observing nature. In his “Observations from Silence” ( 徒然 草 ) Yoshida writes “ Do you only admire the cherry blossoms in their full splendor, the moon only in a cloudless sky? Longing for the moon in the rain, sitting behind the bamboo curtain without knowing how much spring has already come - that too is beautiful and touches us deeply. "

The Zen master Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591) taught a special form of the tea path in which he tried to take up the idea of Wabi-Sabi. Rikyu Wabicha ( 侘び茶 ) are preferred those expressly aesthetic of understatement : "In the narrow tea room, it is important that the utensils are all somewhat inadequate. There are people who reject something even at the smallest defect - with such an attitude you only show that you have not understood anything. "

Iki

Iki ( い き also 粋 ) is one of the classic aesthetic ideals of Japan. It developed in the class of the city dwellers ( 町 人 , chōnin ) in particular the Edokko in Edo during the Tokugawa period . Iki can primarily be described as a habit that was exemplified by the entertainers ( 芸 者 , geisha ). To be Iki was to be “demanding but not satiated, innocent but not naive. For a woman it meant having been around a bit, tasting the bitterness of life as well as the sweetness of life ”. Naturally, the ideal of Iki could only be fulfilled by more mature women. It was also the result of personal development, so not a quirk that you could just emulate. These high character requirements for a geisha also apply to their customers: Iki is the customer if he is well versed in the arts of the actress, shows himself to be charming and knows how to entertain her as well as she does him.

All in all, Iki combines characteristics such as sophisticated urbanity, sophistication, striking esprit, urbane wisdom, the flair of a bon vivant and a flirtatious but tasteful aura of sensitivity.

It was noticed above all by Kuki Shūzō's writing "The Structure of Iki" ( 「い き」 の 構造 ) from 1930. To depict Iki, Kuki relied on the forms of description of Western thought traditions. The writing made the term Iki known in the West as well and led to the question, which is still discussed today, of the extent to which Far Eastern culture and aesthetics can be described with terms borrowed from the Western philosophical tradition. In an imaginary “conversation about language. Between a Japanese and a questioner, ” the philosopher Martin Heidegger recorded these concerns. According to Heidegger, even in our descriptions today, the occidental tradition is based on Greek and Latin terms, the original meaning of which has been increasingly obscured by questionable metaphysical concepts. Central theoretical concepts such as aesthetics , subject , object , phenomenon , technology and nature have freed themselves from the concrete life contexts of antiquity over the centuries and have developed a life of their own that has often remained unquestioned. So if these terms are already problematic for the interpretation of Western art, how much more must there be distortions if they are applied to a completely different cultural area such as Japan.

Yabo

Yabo ( 野 暮 ) can be translated as unpolished , primitive , raw . It was first coined as the opposite of Iki. Based on this narrow meaning, it subsequently found widespread use in everyday language. While Iki is sometimes used excessively and imprecisely, the meaning of Yabo remained relatively narrow. At the same time, of course, there is not always agreement about what exactly yabo is, as it also describes the turning from tasteful ornament into kitsch .

In modern Japanese, industrial products are also sometimes referred to as yabo. For example, if a particularly rough design is to suggest good usability (e.g. mobile phones with large buttons for pensioners), or switches and buttons in the car are printed with the rough katakana syllable instead of the Japanese word in difficult Chinese characters .

Yūgen

Perhaps one of the most elusive terms in Japanese aesthetics is Yūgen ( 幽 玄 ). The term, taken from Chinese, originally means dark , deep and mysterious . The external appearance of Yūgen is similar to the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic, but it points to a dimension lying behind it, which values the implied and hidden more than what is openly and clearly exposed. Yūgen is thus primarily a mood that is open to those hints of a transcendent. This transcendence, however, is not that of an invisible world behind the visible, but that inner-worldly depth of the world in which we live.

The Zen monk Kamo no Chōmei (1153 / 55–1216) gave a classic description of the mood of Yūgen:

“If you look through the fog at the autumn mountains, the view is blurred and yet of great depth. Even if you only see a few autumn leaves, the view is delightful. The unrestricted view that the imagination creates exceeds anything that can be clearly seen. "

Zeami Motokiyo (1363–1443) raised Yūgen to the main artistic principle of No-Theater ( 能 Nō ) . Zeami described it as "the art of ornament in incomparable grace"

Kire

The cutting ( 切 れ Kire ), or abstractly the discontinuous continuity ( 切 れ 続 き Kire-Tsuzuki ) also has its origin in the Zen Buddhist tradition. In the Rinzai school ( 臨 済 宗Rinzai-shū ), the cut as “cutting off the root of life” marks the defeat of all dependencies, a “death” that only liberates to life. This is particularly evident in the Japanese art of arranging flowers ( 生 け 花 , also い け ば な , Ikebana ), in which plants and flowers are artistically designed. Ikebana literally means “living flower”, which apparently stands in contrast to the fact that the flowers have been deprived of their source of life by removing the roots. However, this is precisely what is experienced as “the revival of the flower”. The philosopher Nishitani Keiji (1900–1990) writes :

“However, what appears in Ikebana is a mode of being in which the so-called 'life' of nature is cut off. (...) Because contrary to the fact that the life of nature, although its essence is temporality, turns away from this its essence and thus hides its essence and thus wants to catch up with time in its present existence, the flower turns that of hers Root was cut off, back in one fell swoop to the fate of 'time', which is its original essence. "

Ryōsuke Ōhashi sees in his extensive treatise “Kire. The 'beautiful' in Japan ” which Kire also realizes in other arts. In the no-theater, for example, the movements of the dancers and performers are realized according to the discontinuous continuity. When walking on the stage, the actor lifts his toes slightly and the foot slowly slides across the stage. The movement is abruptly “cut off” by the actor lowering his toes again. This extreme stylization of human walking also reflects the rhythm of life as a connection between life and death ( 生死Shōji ).

Moments of kire can also be found in the poem form of haiku ( 俳 句 ). Here it appears as a cut syllable, such as in the famous haiku by the poet Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694):

「古 池 や

蛙 飛 び 込 む

水 の 音」

"Furuike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto"

"Old pond

A frog splashes into it,

with the sound of the water"

The sudden “ya” at the end of the first line acts as a cut syllable here. By abruptly breaking off the line, all the emphasis is on the pond that comes into view. At the same time, it indicates something that follows it, thus creating continuity with the second and third lines of the poem. For Bashō, however, poetry was also part of the lifestyle. For him, the poet's wanderings meant a farewell to everyday life, a break with one's roots, a cutting off of one's own past self.

The removal and exposure of a natural structure also determines the design of the famous dry garden ( 枯 山水 Kare-san-sui ) in the Ryōan temple. The stone islands are particularly exposed due to the even level of light-colored stones and the rectangular inclusion through the temple wall. As the moss-covered stones resemble the shape of wooded mountains, they refer to the nature surrounding the temple and thus create a discontinuous continuity from the inside to the outside. However, the Kire is not just a moment in room design: thanks to its dry garden layout - 枯 , kare , means “withered, dried up” - the garden depicts a different time than the surrounding nature. While this is subject to the change of the seasons, the stones change and deform infinitely more slowly. Therefore, on the one hand, they are part of the all-encompassing change in nature, on the other hand, they are temporally separated from it, so that a kire-tsuzuki also occurs temporally.

Shibusa

Shibui ( 渋 い ) means simple, discreet, economical and, like Wabi-Sabi, can be used on a wide range of objects - even beyond art. Originally used in the Muromachi period (1336–1392) to denote a bitter taste, it found its way into aesthetics during the Edo period (1615–1868). While “shibui” is the adjective, the associated noun is “Shibusa”.

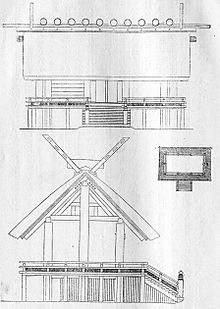

The Japanese Empire played a special role in shaping the Shibusa style . While about military ruler of the shogunate placed their power by the splendor on display, the imperial family demonstrated their claim with elegant restraint. The Ise shrine is an example of this . Its special construction, Shinmei-zukuri ( 神明 造 ), uses planed, but untreated wood, from which simple walls, a straight gable with a straight roof ridge are built. The eaves are supported by some external pillars. Overall, the linear design makes a simple impression and is in sharp contrast to the curved Chinese shapes imported later. Since the rule of the imperial family was legitimized in their relationship with the Japanese gods , it was important to them to keep sanctuaries such as the Ise Shrine free from Chinese influence. In addition, the throne did not always have enough financial means to adapt the latest extravagant styles; in this way one made a virtue out of necessity and stuck to the simple traditional.

Yohaku-no-bi

余 白 の 美 : “The beauty of the leftover white” describes an aesthetic principle in which there is always a free (white) spot in the work of art. Namely, in such a way that not everything is represented, not everything is painted, not everything is said, but a moment of suggestion always remains that points beyond the work itself. In this way there always remains something mysterious, hidden, which can evoke the mood of the Yūgen.

For the critic Morimoto Tetsurō, the emptiness and the inaccessible exposure of the beautiful is an important part of the Japanese aesthetic feeling. Citing the poet Matsuo Bashō , he points out that in poetry, for example, it is important to always leave a remainder unsaid and not to express everything openly.

Contemporary development

Gutai

The Gutai Art Association ( 具体 美術 協会 , Gutai bijutsu kyōkai ) was founded in 1954 by Yoshihara Jirō and Shimamoto Shōzō. Gutai ( 具体 ) means concrete , objective and can be understood as an antonym to abstract , theoretical .

In the Gutai Manifesto from 1956, Yoshihara laments the falseness of all previous art. Instead of revealing their materiality and representativeness, all the materials used only served to represent something other than what they really are. In this way, the materials used are silenced and displaced into insignificance. Gutai art opposes this with a conception of art in which spirit and material have equal rights - the material should no longer be subordinated to the ideas of the spirit. Although the technique of Impressionism gave the first indications, it lacked radicalism. Their material also reappears in old, destroyed and worn works, as the “beauty of decay.” Yoshihara also refers to Jackson Pollock and Georges Mathieu . Ultimately, Gutaiism should go beyond abstract art .

Gutai exhibition at the Biennale di Venezia 2009

Kawaii

A particularly excessive cuteness aesthetic has developed in Japan since around 1970. A characteristic feature is the strong emphasis on the child schema in humans and animals, especially in modern pop culture . This can be done in the style of the Super Deformed up to the point of glaring overemphasis . The characters perceived as "cute" ( 可愛 い or particularly prominent か わ い い ) are often the subject of excessive fan culture , which is discussed in Japan under the heading otaku .

Super flat

Superflat (Japanese transcription of the mostly English word: ス ー パ ー フ ラ ッ ト ) can be seen as a form of critical self-observation or a counter-movement to pop and otaku culture . The superflat art movement tries to unite traditional Japanese culture with the garish pop culture imported from America, to condense it, to compress it superflatly . At the same time, the name alludes to the superficiality of the supposedly "flat" Japanese pop culture.

The market saturation that consumer culture reached in the 1980s initially pushed many existential questions into the background. With the bursting of the Japanese economic bubble ( バ ブ ル 景 気 , Baburu Keiki ) at the beginning of the 90s, an insecure generation arose and a new openness to post-materialist questions. Superflat aims to question the role that modern consumer culture plays in people's lifestyles. At the same time, however, the Superflat artists move in a border region between art and consumption. Takashi Murakami , for example, also mass- produces design objects and the term “superflat” is cleverly used for marketing purposes. As his objects trace the shapes of the otaku in an exaggerated way, they oscillate between criticism and celebration of this culture and, like all Pop Art , do not take a clear position.

Reception in the west

On his trips to Japan, Walter Gropius was fascinated by the consistency of traditional Japanese architecture. Their simplicity is perfectly compatible with the requirements of the western lifestyle: the modular structure of Japanese houses and the room sizes standardized by tatami mats, together with the removable sliding doors and walls, offer Gropius the simplicity and flexibility that they do modern life requires. Bruno Taut also dedicated several works to Japanese aesthetics.

literature

Orientation knowledge

- Jürgen Berndt (Ed.): Japanese Art I and II . Koehler & Arelang Verlag, Leipzig 1975

- Penelope E. Mason, Donald Dinwiddie: History of Japanese Art , 2005, ISBN 9780131176010

- Peter Pörtner : Japan. From Buddha's smile to design. A journey through 2500 years of Japanese art and culture . DuMont, Cologne 2006, ISBN 9783770140923

- Christine Schimizu: L'art japonais . Éditions Flammarion, Collection Vieux Fonds Art, 1998, ISBN 2-08-012251-7

- Nobuo Tsuji autoportrait de l'art japonais . Fleurs de parole, Strasbourg 2011, ISBN 978-2-95377-930-1

- Renée Violet: A Brief History of Japanese Art . DuMont, Cologne 1984, ISBN 9783770115624

Aesthetic theory

- Robert Carter: Japanese arts and self-cultivation . SUNY Press, New York 2008, ISBN 9780791472545

- Horst Hammitzsch : About the terms wabi and sabi in the context of the Japanese arts . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1960

- Eugen Herrigel : The Zen Way . Otto Wilhelm Barth, Munich 1958

- Eiko Ikegami: Bonds of Civility: Aesthetic Networks and the Political Origins of Japanese Culture . Cambridge University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0-521-60115-0

- Toshihiko Izutsu : Philosophy of Zen Buddhism . rororo, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-4995-5428-3

- Toshihiko Izutsu: Consciousness and Essence . Academium , Munich 2006, ISBN 3-8912-9885-4

- Toshihiko & Toyo Izutsu: The Theory of Beauty in Japan. Contributions to classical Japanese aesthetics . DuMont, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-7701-2065-5

- Yoshida Kenko: Reflections from the Silence . Insel, Frankfurt a. M. 2003

- Leonard Koren, Matthias Dietz: Wabi-sabi for artists, architects and designers. Japan's philosophy of humility . Wasmuth, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-8030-3064-1

- Hugo Münsterberg: Zen Art . DuMont, Cologne 1978

- Hiroshi Nara: The Structure of Detachment: the Aesthetic Vision of Kuki Shūzō with a translation of 'Iki no kōzō' . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2004, ISBN 9780824827359

- Ryōsuke Ōhashi : Kire the 'beautiful' in Japan - philosophical-aesthetic reflections on history and modernity . DuMont, Cologne 1994

- Audrey Yoshiko and Addiss Seo: The Art of Twentieth-Century Zen . Shambhala Publications, Boston 1998, ISBN 978-1570623585

- Akira Tamba: (direction), L'esthétique contemporaine du Japon: Théorie et pratique à partir des années 1930, CNRS Editions, 1997

- Tanizaki Jun'ichirō : In Praise of the Shadow : Design of a Japanese Aesthetic . Manesse, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7175-4082-3

- Tanizaki Jun'ichirō: Praise the mastery . Manesse, Zurich 2010; ISBN 978-3-7175-4079-3

- Bruno Taut: The Japanese House and its Life, ed. by Manfred Speidel, Mann, 1997, ISBN 978-3-7861-1882-4

- Bruno Taut: I love Japanese culture, ed. by Manfred Speidel, Mann, 2003, ISBN 978-3-7861-2460-3

- Bruno Taut: Japan's art seen through European eyes, ed. by Manfred Speidel, Mann, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7861-2647-8

Individual studies

- Helmut Brinker : Zen in the Art of Painting . Ex Libris, Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-5026-4082-3

- Anneliese Crueger, Wulf Crueger, Saeko Itō: Paths to Japanese ceramics . Museum of East Asian Art, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-8030-3308-X

- Franziska Ehmcke: The Japanese Tea Way, awareness training and total work of art . DuMont, Cologne 1991, ISBN 3-7701-2290-9

- Wolfgang Fehrer: The Japanese tea house . Niggli, Sulgen Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-7212-0519-7

- Horst Hammitzsch: Zen in the art of the tea ceremony . Otto Wilhelm Barth, Munich 2000, ISBN 9783502670117

- Teiji Itoh: The Gardens of Japan . DuMont, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3-7701-1659-3

- Kakuzō Okakura : The Book of Tea . Insel, Frankfurt a. M. 2002

- Benito Ortolani: The Japanese Theater . Leiden, Brill 1990, ISBN 0-6910-4333-7

- Jana Roloff, Dietrich Roloff: Zen in a cup of tea . Ullstein Heyne List, Munich 2003

- Ichimatsu Tanaka: Japanese Ink Painting: Shubun to Sesshu . Wetherhill / Heibonsha, New York / Tokyo 1972, ISBN 0-8348-1005-0

- Inahata Teiko: What a silence - The Haiku teaching of Takahama Kyoshi . Hamburger Haiku Verlag, Hamburg 2000

- Masakazu Yamazaki and J. Thomas Rimer: On the Art of the No Drama: The Major Treatises of Zeami. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1984, ISBN 0-691-10154-X .

See also

Web links

- Graham Parkes: Japanese Aesthetics. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Jürgen Gad: Japanese aesthetics

- David and Michiko Young Japanese Aesthetics (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ See on the double difference: Heise, Jens: Nihonron. Materials on cultural hermeneutics. In: Ulrich Menzel (Ed.): In the shadow of the winner: JAPAN. , Vol. 1, Frankfurt am Main 1989, pp. 76-97.

- ↑ See Graham Parkes: Japanese Aesthetics , SEP, Stanford 2005.

- ↑ See Mori Mizue: "Motoori Norinaga" . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , April 13, 2006 (English).

- ↑ Quoted from: Peter Pörtner , Jens Heise : Die Philosophie Japans. From the beginnings to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 431). Kröner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-520-43101-7 , p. 319.

- ↑ a b Otto Ladstädter, Sepp Linhart : China and Japan. The cultures of East Asia . Carl Ueberreuter, Vienna 1983, p. 305 .

- ↑ 高橋 睦 郎 (Takahashi Atsuo?): 狂言 ・ 正言 (1/2) . November 9, 1995; Retrieved June 7, 2012 (Japanese).

- ↑ を か し (お か し) . (No longer available online.) Yahoo, 2012, formerly original ; Retrieved June 7, 2012 (Japanese, It is the Yahoo 百科 事 典 (Yahoo Encyclopedia)). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ See Leonard Koren: Wabi-sabi for artists, designers, poets & philosophers . Imperfect Publishing, 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ See the entry Wabi in Wadoku .

- ↑ See Leonard Koren: Wabi-sabi for artists, designers, poets & philosophers . Imperfect Publishing, 2008, p. 21 f.

- ↑ See Andrew Juniper: Wabi sabi: the Japanese art of impermanence , Tuttle Publishing, 2003, p. 129.

- ↑ Donald Richie: A tractate on Japanese aesthetics . Berkeley 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Yoshida Kenkō: Reflections from the Silence . Frankfurt am Main 1991, p. 85. For this interpretation cf. Graham Parkes: Japanese Aesthetics , SEP, Stanford 2005.

- ↑ Stephen Addiss, Gerald Groemer, J. Thomas Rimer: Traditional Japanese arts and culture: an illustrated sourcebook . Honolulu 2006, p. 132.

- ↑ Liza Crihfield Dalby: Geisha . Berkeley 1983, p. 273.

- ↑ See ibid., P. 279.

- ↑ Cf. Taste of Japan, 2003 ( Memento from July 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Full text in the Japanese original , German translation: The structure of "Iki" by Shūzō Kuki: an introduction to Japanese aesthetics and phenomenology , Volume 1163 by Deutsche Hochschulschriften , Fouque Literaturverlag, 1999.

- ↑ See Heidegger Complete Edition , Volume 12, Frankfurt am Main 1985.

- ↑ See Andrew A. Tsubaki: Zeami and the Transition of the Concept of Yugen. A Note on Japanese Aesthetics In: The Journal of Aesthetics and Criticism , Vol. XXX / l, Fall, 1971, pp. 55-67, here p. 56.

- ↑ See Graham Parkes: Japanese Aesthetics , SEP, Stanford 2005.

- ↑ Quoted from: Haga Kōshirō: The Wabi Aesthetic through the ages . In: H. Paul Varley, Isao Kumakura (ed.): Tea in Japan: essays on the history of chanoyu Honolulu 1989, p. 204.

- ↑ Zeami, J. Thomas Rimer, Masakazu Yamazaki: On the art of the nō drama: the major treatises of Zeami . Princeton 1984, p. 120.

- ↑ See Graham Parkes: Japanese Aesthetics , SEP, Stanford 2005.

- ↑ Nishitani Keiji: Ikebana. About pure Japanese art . In: Philosophisches Jahrbuch 98, 2, 1991, pp. 314-320. Quoted from: Ryōsuke Ōhashi: Kire. The 'beautiful' in Japan. Philosophical-aesthetic reflections on history and modernity. Cologne 1994, p. 68.

- ↑ Cf. Ryōsuke Ōhashi: Kire. The 'beautiful' in Japan. Philosophical-aesthetic reflections on history and modernity. Cologne 1994, p. 14.

- ↑ Transcription and translation according to Ryōsuke Ōhashi: 'Iki' and 'Kire' - as a question about art in the age of modernity. In: The Japanese Society for Aesthetics (Ed.): Aesthetics , Tokyo March 1992, No. 5, pp. 105-116.

- ↑ Cf. Ryōsuke Ōhashi: 'Iki' and 'Kire' - as a question of art in the age of modernity. In: The Japanese Society for Aesthetics (ed.): Aesthetics , Tokio March 1992, No. 5, pp. 105-11, here p. 106.

- ↑ Cf. Ryōsuke Ōhashi: Kire. The 'beautiful' in Japan. Philosophical-aesthetic reflections on history and modernity. Cologne 1994, p. 65.

- ↑ a b See David and Michiko Young: Japanese Aesthetics ( Memento of the original from July 13, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Chapter 2, par. Role of the Imperial Family .

- ↑ See Encyclopedia of Shinto: History and Typology of Shrine Architecture . Section Shinmei-zukuri .

- ↑ Cf. Marc Peter Keane, Haruzō Ōhashi: Japanese garden design . Boston / Tokyo, p. 57.

- ↑ See Morimoto Tetsurō: Kotoba e no tabi . Tōkyō 2003, p. 138, online .

- ↑ According to Shimamoto's website, he and Yoshihara founded the group together. See Shimamoto's biography .

- ↑ See the English translation of the Gutai Manifesto ( RTF ; 12 kB). Originally published / published in Geijutsu Shincho .

- ↑ See Hunter Drohojowska-Philp: Superflat on artnet.com 2001.

- ↑ Cf. Kitty Hauser: Superflat: Kitty Hauser on fan fare ( memento of July 8, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ). In: Artforum International Magazine , 2004.

- ↑ See Walter Gropius, Kenzo Tange , Yasuhiro Ishimoto : Katsura. Tradition and Creation in Japanese Architecture . Yale University Press, New Haven 1960.