Japanese temple architecture

Japanese temple architecture describes a form of Japanese architecture for Buddhist temples . In Japan, Buddhist sacred buildings are called temples ( jiin ) and those of Shinto are called shrines ( jinja ). Today there is temple architecture made of concrete, but the premodern temples were all built in wood. As a result of sponge formation, insect damage, rotting, lightning strikes, destruction by typhoons, the effects of war, etc., they had to be relentlessly restored and, if completely destroyed, also rebuilt. Here one often integrated contemporary style elements.

Three main styles and one eclectic style

While the architectural styles of sacred buildings in Europe can usually be easily identified, the differences in Japan are less noticeable. A few details help classify the temples in terms of style and time. Two styles are most commonly observed: the “Japanese style” ( 和 様 Wayō ) and the “Zen style” ( 禅宗 様 Zenshūyō ). There are only a few examples of the third style, the “Daibutsu style” ( 大 仏 様 Daibutsuyō ). Another group of temples shows an "eclectic style" ( 折衷 様 setchū-yō ).

Japanese style

With Buddhism, a highly developed Chinese temple architecture came to Japan from the 6th century, which was adapted to local tastes. The buildings appear lighter, especially the wooden pagodas show their own Japanese characteristics.

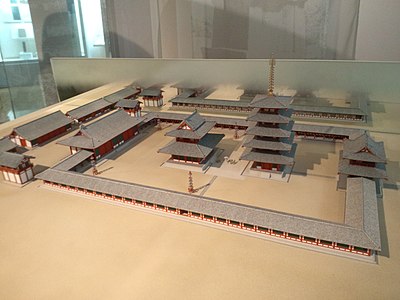

The buildings of this "Japanese style" were erected as part of a temple complex called garan ( 伽藍 ). The name derives from the Sanskrit saṃghārāma , the resting and meditation place of the monks, which was written in Japanese as sōgya ranma ( 僧伽 欄 摩 ). . The early form, now known as the “seven-hall system of the southern capital” ( Nanto-shichidō-garan , 南 都 七 堂 伽藍 ), consisted of seven buildings arranged in a right-angled floor plan:

Famous examples of this are the Shitennō Temple ( Shitennō-ji ) in Osaka , built by the Crown Prince Shōtoku around 623 , which was rebuilt according to old plans after its destruction in the Second World War, and the Hōryū Temple ( Hōryū-ji ), which also goes back to Shōtoku. With the construction of the imperial city Heijō-kyō (today Nara ) from 710 a number of temples were built. Some remained more or less completely preserved even after the Tennō moved to Heian-kyō ( Kyōto ). The name "Japanese style" ( wayō ) only came up in the Kamakura period when new Chinese styles came into the country and the differences became aware.

Daibutsu style

After the Tōdai Temple ( Tōdai-ji ), which dates from the 8th century, was destroyed in armed conflicts at the end of the Heian period , it was rebuilt in the "Daibutsu style" that was taken over from China, literally the Grand Buddha style . At the end of the 16th century the complex was destroyed again. During the reconstruction in 1705, the size was reduced and contemporary elements were added. Therefore, the “Daibutsu style” is only preserved in its pure form in Nara at the “Great South Gate” ( 南 大門 Nandaimon ). Another example is the Jōdō Temple ( Jōdō-ji ) in Hyōgo Prefecture .

Zen style

In the Kamakura period , Zen Buddhism brought the architecture of the Chinese Song Dynasty to the country. The structures are smaller with a noticeably high roof. With larger Zen temples, however, the difference to the “Japanese style” is less clear.

With Zen there was also a change in the design of the building arrangement. There are no pagodas in the zen temple complexes ( Zenshū garan 禅宗 伽藍 ). If possible, the buildings are oriented along a longitudinal axis:

Above all in Kamakura, however, where the temples were built in mountain niches, the strictly desired arrangement of the buildings was dispensed with.

Comparison of styles

The three styles differ in more or less noticeable details.

- "Japanese style" temples have roofs with eaves beams that are slightly raised at the corners ( noki kaeri 軒 返 り ). They have a raised wooden floor, the columns stand on a vaulted foundation ( rengeza 蓮華 座 , literally lotus seat ), and there are only bolted or laid cross beams between the columns. Spacers ( kaerumata 蛙 股 ・ 蟇 股 , lit. frog legs) can be found between the crossbars . The windows are rectangular in shape and have wooden grilles.

- Temples and other structures in the "Daibutsu style" are rare. Their most striking feature are the protruding cross-wood brackets ( 肘 木 hijiki ) above the pillars .

- "Zen-style" temples also have roofs with raised eaves ( noki kaeri ) at the corners. The floor is not raised, covered with stone slabs or just tamped clay. The pillars rest on round stone slabs ( garan-ishi or garan-seki 伽藍 石 ). There are inserted crossbeams that give greater stability. The spacers between the crossbars have a geometric shape. The windows often have a bell shape and are then called kato-mado ( 火 灯 窓 ・ 花 頭 窓 , roughly equivalent to fire lamp windows or flower head windows).

The temples often have a mirror ceiling that is occasionally painted with a dragon. If you are in the center below and clap your hands, you hear an echo, the "dragon laughter". Examples are the dragons painted by Kanō Tan'yū in the teaching hall of the Myōshin Temple ( Myōshin-ji ) or the teaching hall of the Shōkoku Temple ( Shōkoku-ji ).

wavy verge ( karahafu ) over the central part of the Tōdai temple (Todai-ji)

Edo period

At the beginning of the Edo period , the Ōbaku school ( Ōbaku-shū 黄 檗 宗 ) came to Japan, another Zen Buddhist denomination that brought its own style. Its center is in the south of Kyoto Prefecture, and beyond that it is hardly widespread architecturally.

Many of today's “old temples” are rebuilds from the Edo period. This can often be recognized by the curved Chinese verge and ornamental gable ( 唐 破 風 karahafū ).

20th century

After the Great Kantō earthquake in 1923, the destroyed Hongan Temple in the Tokyo district of Tsukiji ( Tsukiji Hongan-ji ) was rebuilt by Itō Chūta in the "Indian style" in the years 1931 to 1934 . Large numbers of temples went up in flames during World War II. During the reconstruction, the former form of the wooden structure was often imitated in concrete.

There are also experiments with old and new building materials and shapes. One of the remarkable examples of modern temple architecture is the Buddha Hall ( Shakaden ) of the new religious "Society of Friends of Spirits" ( Reiyūkai ) in Tokyo , which is also worth seeing inside . The award-winning worship hall of the Ekō Temple (Ekō-in Nenbutsudō 回 向 院 念 仏 堂 ) by Kawahara Yutaka in Tokyo (Sumida-ku, Ryōgoku) as well as that of Andō Tadao 2001 Kōmyō- is even more radical in its form while preserving the spiritual atmosphere . Temple (Kōmyō-ji) in Saijō ( Ehime Prefecture ) 2001.

- Examples

Tsukiji Hongan Temple ( Tsukiji Hongan-ji ) in Tokyo

Details and technical terms

Arrangement of the temple complexes

The term Shichidō garan ( 七 堂 伽藍 ), usually shortened to garan , only appears in texts from the Edo period . It has since been understood as the name of a temple complex with seven halls ( shichidō ). But the descriptions of temples in ancient scripts as well as the systems that have survived to this day show great differences in terms of the number of buildings and their arrangement. Originally the pagoda, in which relics were deposited, played the most important role. Over time, the gold hall ( kondō ) with its statues and pictures gained in importance and moved into the center of the complex. In the end, Zen temples dispensed with pagodas entirely.

Model of the Shitennō Temple ( Shitennō-ji ) in Osaka

Layout of the Hōryū temple ( Hōryū-ji ), Nara prefecture: A central gate, B tour, C gold hall, D pagoda, E teaching hall, F sutrenspeicher, G bell tower

Yakushi temple ( Yakushi-ji ) in Nara: A central gate, B tour, C gold hall, D pagoda, E teaching hall, F bell tower, G sutrenspeicher

Zuiryū Temple ( Zuiryū-ji ), a temple of the Sōtō Zen School in Takaoka ( Toyama Prefecture ): A front main portal, B Gate of the Three Liberations, C Tour, D Buddha Hall, E Teaching Hall, F Zen Hall (meditation hall) , G bell tower, H residential and farm buildings

roofs

The large roofs are an essential element of the temple. They usually run out in curves with an elaborately designed substructure. There are the following types:

- Gable roof ( 切 妻 kirizuma )

- Hipped roof ( 寄 棟 yosemune )

- Hipped foot roof ( 入 母 屋 irimoya )

- Cripple hipped roof ( 半 切 妻 han-kirizuma )

- Pyramid roof ( 方形 ・ 宝 形 hōgyō )

Roofs are occasionally extended by covering the entrance ( 向 拝 kōhai ) or by canopies ( 廂 ・ 庇 hisashi ). Edge roofs ( 裳 階mokoshi ), which optically increase the number of floors, are particularly found on pagodas .

- Examples

Roof shape yosemune in the Tōshōdai temple ( Tōshōdai-ji ), Nara

Roof shape irimoya of the Daigo Temple ( Daigo-ji ), Kyoto

Roof shape hōgyō of the Ukimi Hall ( Ukimidō ), Katata

Roof shape hōgyō at the Kōfuku Temple ( Kōfuku-ji ), Nara

Columns and capitals

When looking at the entrance, the side arrangement of the columns is called keta-yuki ( 桁 行 ). This corresponds to the direction the ridge is pointing. The arrangement in the deep is called hari-yuki ( 梁 行 ) or harima ( 梁 間 ). The front view of the building always shows an odd number of gaps, whereby the keta-yuki grows larger from the edge to the center in order to emphasize them. The columns of the early Nara period sometimes have a slightly bulbous shape ( entasis ).

The European capital corresponds to a wooden structure, often staggered several times ( kumimono 組 物 ). To support the weight of the heavy roof, tiered capitals were placed on the pillars. The protruding steps of the crossbar brackets ( hijiki ) are counted in the form futa-tesaki , mi-tesaki , etc.

- Examples

two-stage bracket ( Futa-tesaki ) in the Sanmon gate of the Kenchō Temple ( Kenchō-ji )

three-step bracket ( mi-tesaki ) in the sanmon gate of the daitoku temple ( daitoku-ji )

Pagodas

The pagoda ( 塔 tō ) comes in two basic types. The "Vielschatz-Pagoda" ( tahōtō多 宝塔 ), which can be found mainly in plants of Shingon Buddhism and Tendai Buddhism , has two floors . It got its name in allusion to the Prabhūtaratna -Buddha (Tahō Nyorai 多 宝 如 来 ), which is described in the 11th chapter of the Lotus Sutra sitting in a jewel stupa. Their small shape is called "Treasure Pagoda" ( hōtō 宝塔 ). Today this term is also used to denote pagodas with a round structure in contrast to those with a square floor plan.

The second basic type is called a three-story pagoda ( sanjū-no-tō , 三重 塔 ), five-story pagoda ( gojū-no-tō , 五 重 塔 ), etc. with the respective number of (optical) floors . Because of the fringed roofs ( mokoshi ) attached here and there , this number does not always correspond to the number of actual floors inside the building.

There are also special forms, such as the octagonal pagoda of the Anraku Temple Anraku-ji in Nagano or the thirteen-story pagoda of the Tanzan Shrine (Tanzan-Jinja) near Sakurai (Nara) .

- Examples

"Vielschatz-Pagoda" ( tahōtō ) on the Kōyasan , Wakayama Prefecture

three-story pagoda in Kofuku Temple

( Kōfuku-ji ), Narafive-story pagoda in Daigo Temple ( Daigo-ji ), Kyoto

octagonal pagoda of Anraku Temple (Anraku-ji) in Nagano

Gates

There are hardly any German equivalents here:

- kabuki-mon ( 冠 木門 ), crossbar gate

- agetsuchi-mon ( 上 土 門 )

- muna-mon ( 棟 門 ), gate with a gable roof over the transom

- yakui-mon ( 薬 医 門 )

- shikyaku-mon ( 四脚 門 ), four-legged gate (with four main pillars)

- hira karamon ( 平 唐門 ), broad China gate

- mukai karamon ( 向 か い 唐門 )

- kōrai-mon ( 高麗 門 ), Korea Gate

- hakkyaku-mon ( 八 脚 門 ), eight-footed gate (with eight main pillars)

- rō-mon ( 楼門 ), (two-story) tower gate

- nijū-mon ( 二 重 門 ), double gate

- Examples

four-footed gate ( shikyaku-mon ) of the Hōryū Temple ( Hōryū-ji ), Nara Prefecture

Korea Gate ( kōrai-mon ) of the Yakushi Temple ( Yakushi-ji ), Nara

eight-footed gate ( hakkyaku-mon ) of the Hōryū Temple ( Hōryū-ji ) in Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture

Tower gate ( rō-mon ) of the Hannya Temple ( Hannya-ji ), Nara

yakui-mon of the Kūin Temple ( Kūin-ji ), Obama ( Fukui Prefecture )

See also

Remarks

- ↑ The word garan appears for the first time in the old historical work Nihonshoki (552).

- ↑ Southern capital ( nanto ) was an alternative name for Nara.

- ↑ Possibly there is a misinterpretation of the similar sounding name shitsudō ( 悉 堂 , literally “all halls”, “total temple ”) ( Kōsetsu Bukkyō Daijiten 広 説 仏 教 語 大 辞典 ).

- ↑ This type was often adopted by shrines.

literature

- Nobuo Ito, Masaru Sekino, Hirotarō Ota (eds.): Bunkazai kōza Nihon no kenchiku [Series on Cultural Properties: The Architecture of Japan]. 5 vol., Tōkyō: Daiichi Hōki Shuppan, 1976–1977 ( 伊藤 延 男 [ほ か] 編. 文化 財 講座 日本 の 建築. 第一 法規 出版 )

- Minoru Ōoka: Nara no tera (The temples in Nara). Nihon no bijutsu, Volume 7, Tōkyō: Heibonsha 1965.

- Alexander Soper, Alexander Coburn: The Evolution of Buddhist Architecture in Japan . New York: Hacker 1979, ISBN 0-87817-196-7 .