Carthusian monastery Mainz

|

|

|

|---|---|

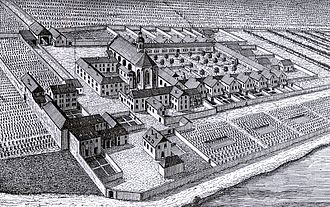

| The location of the Charterhouse on a map of the city of Mainz around 1689. |

The Carthusian Monastery of Mainz is a lost Carthusian monastery in the Rhineland-Palatinate state capital Mainz , of which the street "Kartaus" still reminds us.

history

The Carthusian Monastery of St. Michael was on the Michelsberg in what is now the Upper Town of Mainz . Archbishop Peter von Aspelt had given this place to the Carthusians in 1320 for the desired construction of a monastery. The convent was ready for occupancy as early as 1324 and was settled by monks from the St. Peterstal Charterhouse near Kiedrich in the Rheingau. The construction of the church began in 1330, it was consecrated in 1350 by Auxiliary Bishop Albert von Beichlingen . The Mainz Charterhouse was the first on German soil. On the occasion of the 700th anniversary of the settlement, the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum (Mainz) will show a cross-institutional exhibition with a catalog and an accompanying scientific program under the title "The incomparable precious Carthaus" in 2021 . Emperor Karl IV took the Charterhouse under protection in 1361, granted it privileges and assigned it to the care of the Reichsschultheissen von Oppenheim . In 1434/35 Dominic of Prussia , the creator of today's rosary , worked here as novice master . On August 22, 1552, during the Second Margrave War , the monastery fell victim to the destruction of Margrave Albrecht II Alcibiades of Brandenburg-Kulmbach . Rebuilt in 1613, the buildings survived the Thirty Years' War and the siege in the Palatinate War of Succession largely unscathed. In the latter , the commander-in-chief, Duke Karl of Lorraine , as well as Elector Max Emanuel of Bavaria and Elector Johann Georg III. of Saxony set up their headquarters in the monastery buildings.

In 1712 Michael Welcken took up his post as prior and led the Charterhouse to a new bloom. He renovated all the buildings, had the church beautifully painted in 1715 and equipped its choir with valuable high altars and, from 1723 to 1726, with artistic stalls, under the direction of the Hamburg art carpenter Johann Justus Schacht . On the southern side of the cloister stood the church, opposite a chapel, on the other sides there were 22 cell tracts for the monks, each of which consisted of a vestibule, room, kitchen, attic, workhouse, cellar and garden.

Elector Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal had the Charterhouse on August 24, 1781 by Pope Pius VI. cancel. The monastery assets were transferred to the newly established university fund . The assembled monks were informed of this decision on November 15 of that year and they could either move to the Erfurt Charterhouse or from now on live as secular priests . In 1788 the elector bought the entire complex for 83,000 guilders and had the church including the cloister, chapel and residential buildings demolished between 1790 and 1792. He connected the site with the neighboring garden of his Favorite Palace , which was completely destroyed in 1793.

At the former location of the Carthusian monastery is now the street Kartaus , where there is also a "Kartaus fountain" with the figure of the founder of the order St. Bruno of Cologne in memory of the convent since 1912 .

Library

The existence of a library for the early days of the Carthusian monastery cannot be proven by sources , but based on knowledge of the order's affinity for books , its unconditional reference to writing and the distinctive book culture, it can be assumed that no later than the second half of the 14th century its own library room existed within the Mainz Charterhouse. The original holdings of liturgical manuscripts, Bibles and Bible commentaries increased during this time through gifts from benefactors and through books brought with them by the brothers when they entered the order. Through their writing activity, the monks themselves significantly increased the inventory.

With 624 codices from the Mainz Carthusian provenance , the Scientific City Library Mainz has a remarkably high number of traditional manuscripts from a medieval library . The outstanding ensemble value and the importance of the testimonies of order-specific piety contained here have been known in international research for many decades. A special feature within the fund is the Carthusian lay library with around 100 German-language manuscripts, primarily ascetic content for lay brothers.

The high status that the book enjoyed in the Reformed Order of the Carthusian monks is reflected in the care taken in copying texts and in their own regulations for the emendation activity for text corrections. The fact that this resulted in an important function for Carthusian manuscripts as reliable templates for book printing was also manifested in the collaboration with the early local printing works in the Gutenberg city of Mainz . The surviving manuscript catalog from 1466/70, which is supplemented by a further catalog from the early 16th century, has a unique source value for the late medieval library administration in general and for the arrangement system of the Mainz Kartausebibliothek. Catalog I, with the registers of the Basel and Erfurt Charterhouse, is one of the most extensive medieval library catalogs .

A large proportion of the manuscripts of the Mainz Charterhouse are already cataloged; their development is ongoing. The manuscripts Hs I 1 - Hs I 350 have been published in printed catalogs by the Harrassowitz publishing house . Volume IV with the shelfmarks Hs I 351–490 should be ready for printing in the medium term. The current cataloging takes place in Manuscripta Mediaevalia. The largest scattered holdings from the provenance of the Mainz Charterhouse are today in Oxford (Laud) and in London (Arundel). During the Thirty Years' War they came to the Bodleian Library through Archbishop William Laud and to the British Library through Thomas Howard , Earl of Arundel . The University Library of Basel also has a number of Mainz Carthusian monuments. The holdings that were dislocated after the Carthusian monastery was dissolved in 1781 will be virtually merged again in a DFG project at Heidelberg University Library : Bibliotheca Cartusiana Moguntina - digital. Virtual map library Mainz . The focus is on the codices preserved in the city library.

Received inventory

The three baroque high altars of the Carthusian Church in Mainz are now in the basilica of St. Marcellinus and Petrus zu Seligenstadt . The main altar was designed by Maximilian von Welsch as a ciborie altar in 1715 . It is a canopy resting on pillars, flanked below by the four ancient doctors of the Church, Jerome , Ambrose of Milan , Augustine of Hippo and Pope Gregory the Great . John the Baptist , St. Joseph with baby Jesus , Rabanus Maurus and St. Bonifatius sit on the fighter plates .

Parts of the inlaid choir stalls later ended up in Trier Cathedral .

In the chapel of Burg Bischofstein near Münstermaifeld there is an inlay door from the Mainz Charterhouse.

literature

- Fritz Arens : Construction and equipment of the Mainz Charterhouse. ( Contributions to the history of the city of Mainz ; 17), Mainz 1959.

- Fritz Arens : Two altarpieces from the Mainz Charterhouse. In: Mainzer Zeitschrift 54 (1959), pp. 90–93.

- Mechthild Baumeister / Susan Müller-Arnecke: The changes to a baroque choir stalls dorsal from the former Carthusian monastery in Mainz. In: Journal for Art Technology and Conservation 3 (1989), pp. 378–393.

- Karl Johann Brilmayer : Rheinhessen in the past and present. History of the existing and departed cities, towns, villages, hamlets and farms, monasteries and castles in the province of Rheinhessen. 1905, reprinted Würzburg 1985.

- Uta Goerlitz: Monastic book culture and intellectual life in Mainz at the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern age. The Charterhouse of St. Michael and the Benedictine Monastery of St. Jakob (on the origin of the Mainz Augustine manuscript I 9). In: Geesche Hönscheid / Gerhard May (Hrsg.): The Mainzer Augustinus sermons. Studies on a find of the century. ( Publications of the Institute for European History Mainz. Dept. for Occidental Religious History ; Supplement 49), Mainz 2003, pp. 21–53.

- Wilhelm Jung: A rediscovered marble altar of St. Maria Magdalena from the Mainz Charterhouse . In: Yearbook for the Diocese of Mainz 8 (1958–1960), pp. 333–340.

- Daniela Mairhofer: The medieval manuscripts from the Charterhouse at Mainz in the Bodleian Library. 2 vols., Oxford 2018.

- Michael Oberweis: The beginnings of the Mainz Charterhouse: an old order in a new environment. In: Archive for Middle Rhine Church History 65 (2013), pp. 83-104.

- Oberweis, Michael: Heinrich Egher von Kalkar and his relationship with the Mainz Charterhouse. In: Hermann Josef Roth (Hrsg.): The Carthusians in the focus of science: 35 years of international meetings. 23-25 May 2014 in the former Cologne Charterhouse, Salzburg 2015, pp. 82–90.

- Annelen Ottermann: Dei verbum manibus predicemus. Book culture among the Carthusians. In: Wolfgang Dobras (Red.): Gutenberg - aventur and art, From secret company to the first media revolution. Mainz 2000, p. 276.

- Annelen Ottermann: The history of the Mainz Charterhouse. In: Wolfgang Dobras (Red.): Gutenberg - aventur and art, From secret company to the first media revolution. Mainz 2000, p. 277.

- Annelen Ottermann: This book is the Carthuser by Mentz. The library of the Mainz Charterhouse. In: Wolfgang Dobras (Red.): Gutenberg - aventur and art, From secret company to the first media revolution. Mainz 2000, pp. 277-278.

- Hermann Josef Roth: Mainz , in: Monasticon Cartusiense , ed. by Gerhard Schlegel, James Hogg, Volume 2, Salzburg 2004, 556-562.

- Friedrich Schneider (clergyman) : The treasure registers of the three Mainz monasteries Karthaus, Reichen Klaren and Altenmünster when they were abolished in 1781. Mainz 1902

- Friedrich Schneider (clergyman) : An artist colony of the eighteenth century in the Carthusian monastery at Mainz according to documented sources. , Mainz 1902.

- Heinrich Schreiber: The library of the former Carthusian monastery in Mainz. The manuscripts and their history. ( Supplements to the Zentralblatt für Bibliothekswesen ; 60) Leipzig 1927 ( online ).

- Heinrich Schreiber, Heinrich: The library of the Mainz Charterhouse and the binding research. In: monthly sheets for book covers and handbinding 3 (1927), pp. 3–10.

- Johannes Simmert: The history of the Carthusian monastery at Mainz ( contributions to the history of the city of Mainz ; 16). Mainz 1958.

- Friedrich Stöhlker: Supplements to the history of the Mainz Charterhouse. In: Mainzer Zeitschrift 66, 1971, pp. 45–57.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ "Peterstal (desert), Rheingau-Taunus district". Historical local dictionary for Hessen. In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

- ↑ http://www.dommuseum-mainz.de/die-unvergleichliche-kostbare-carthaus/

- ^ Website of the city of Mainz on the Kartaus fountain ( Memento from May 23, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0128-3-2174

- ↑ http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0128-3-1701

- ↑ Gerhard set / Gerhardt Powitz: The manuscripts of the City Library Mainz . Vol. 1: Hs I 1-150. Wiesbaden 1990. Gerhard List: The manuscripts of the Mainz city library . Vol. 2: Hs I 151-250. Wiesbaden 1998. Gerhard List: The manuscripts of the Mainz city library . Vol. 3: Hs I 251-350. Wiesbaden 2006.

- ↑ http://www.manuscripta-mediaevalia.de/info/projectinfo/mainz.html

- ↑ https://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/wir/projekt_mainzer-kartause.html

- ^ Paul-Georg Custodis: The Mainz Charterhouse and the fate of its choir stalls , Rheinische Heimatpflege NF 44 (2007), pp. 7-20

Coordinates: 49 ° 59 ′ 19.2 " N , 8 ° 17 ′ 11.3" E