Kerberos (genus)

| Kerberos | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kerberos skull (holotype) |

||||||||||||

| Temporal occurrence | ||||||||||||

| Middle Eocene ( Bartonian ) | ||||||||||||

| 40.4 to 37.7 million years | ||||||||||||

| Locations | ||||||||||||

|

Europe (France) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Kerberos | ||||||||||||

| Solé , Amson , Borths , Vidalenc , Morlo & Bastl , 2015 | ||||||||||||

Kerberos is a genus in the order Hyaenodonta , extinct carnivorous mammals that may beclose to predators . It lived in the Middle Eocene 40 to 38 million years ago. The only remainsknownso far are from a site in southern France , where the bones were recovered in the early 1980s. They consist of the skull, the lower jaw, and some parts of the hind leg. Due to its size, one of the largest known hyaenodonts of the Eocene can be inferred. The animals had specialized teeth that were well suited for cutting meat-based foods. At that time they may have occupied the ecological niche of today's hyenas . The genus was scientifically introduced in 2015.

description

Kerberos is one of the great representatives of the hyaenodonts. The body weight was estimated to be around 140 kg, but the range is between 49 and 277 kg, depending on the determination method used. The genus has been handed down from a complete skull, a lower jaw and various elements of the hind leg. The skull reached a length of 35 cm, which corresponds in size to that of a female brown bear . Due to the deposition environment, the skull is slightly crushed and splintered into individual bones, making individual features unrecognizable. It was characterized by the short rostrum , which was shorter than that of Hyaenodon , but not as distinct as that of Megistotherium . The lower surface of the interior of the nose was at an angle of 45 ° in side view. It was laterally framed by the median jawbone . This ended just behind the approach of the inside of the nose. The upper jaw increased in height from front to back, making the rear end twice as high as the front. The infraorbital foramen was above the fourth premolar . The nasal bone was narrow and triangular when viewed from above. It reached back beyond the position of the orbit . The large tear bone protruded from the edge of the eye to the front of the face. The zygomatic arch was massive and expansive, and very high when viewed from the side. The front branch approach was almost straight. The frontal bone traversed prominent temporal lines, which united on the parietal bone to form an extremely strong parietal ridge. This had a considerable height, which in the rear section almost corresponded to that of the rest of the skull. The bulge of the occiput arched over the occipital opening and led down on both sides of the skull. It ended typically for the Hyainailouridae above the mastoid process. On the palatine bone , the choans opened at about the end of the row of teeth.

The lower jaw had a noticeably low horizontal bone body in front, which is considered to be relatively original among the Hyainailourids. The symphysis expanded to the third premolar. A mental foramen was located under the first and last premolars . The lower edge of the horizontal bone body ran slightly convex to the angular process, which was short and sharp. The mandibular joint was only slightly above the occlusal plane. It had a cylindrical shape that widened at the side. The front edge of the crown process, which rose at an angle of 45 ° to the rest of the ascending branch, had a deep furrow. This became too prominent, especially towards the lower end, and acted as an anchor point for the lower jaw muscles. A conspicuous masseteric fossa was also formed as a muscle attachment point on the side of the ascending branch.

The upper teeth consisted of three incisors , one canine , four premolars and three molars per half of the dentition, the front teeth of the lower teeth are unknown. The first incisor was the smallest, the third the largest. All had a simple conical shape, the last one resembling a canine tooth. The crowns of the canines have not survived. The premolars appeared triangular in side view, caused by a large main cusp, the paraconus in the upper jaw and the protoconid in the lower jaw. The posterior premolars also had individual secondary humps. In the lower jaw, only a short diastema separated the first two premolars. The molars had a sectorial structure with typically three main cusps (Para-, Proto- and Metaconus in the upper jaw and Para-, Proto- and Metaconid in the lower jaw). On the first two maxillary molars, the para- and metaconus were combined to form the amphiconus, and the paraconus also exceeded the metaconus in height, which is characteristic of the Hyainailourids. In contrast to Akhnatenavus , the two cusps could not be distinguished by a small furrow. The protoconus was very small. The metaconus was missing from the rearmost upper molar, which meant that it was shortened in length. The lower molars had only a short talonid (a deeper area of the chewing surface) that appeared simple due to the lack of additional cusps. The metaconide was reduced. In the upper rear row of teeth, the teeth increased more or less continuously in size from the first premolar to the second molar, the corresponding lengths of the two teeth were 11.4 and 23.5 mm, the last molar only reached a length of 9.2 mm. In the lower jaw, the increase in size continued up to the last molar. Here the first premolar was 16.5 mm and the last molar 25.8 mm. In both the upper and lower halves of the dentition, however, the last premolar was slightly larger than the first molar.

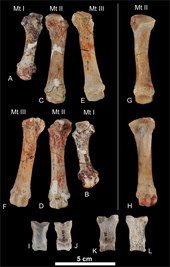

The few postcranial skeletal elements belong to the lower section of the hind leg. The fibula was 19.3 cm long and had a large lower joint end that articulated with the calcaneus . The bone was not attached to the shin . Both the heel and the talus are poorly preserved. The latter had a flat dented talus roll and a wide joint head on a short neck. The metatarsals were short and sturdy with cylindrical shafts, their lengths were 5.8 and 7.8 cm for those of the first and third rays. The limbs of the toes were also short and sturdy.

Fossil finds

The only fossil remains of Kerberos so far were discovered at the site of Montespieu near Lautrec, northwest of Castres in the Tarn department in southern France . They camped there in sandstone layers of the formation of the Molasses de Saix et de Lautrec (the so-called Grès de Puech Auriol et de Venès ). The site has been known since at least 1851, when Jean-Baptiste Noulet mentioned the first fossil bones. Their wealth of fossils prompted Hans Georg Stehlin to submit an extensive description in 1904. In this he presented, among other things, remains of the tapir relative Lophiodon , the horse relative Palaeotherium or the hippo relative Choeropotamus . Significant research took place in the 1970s and 1980s under the direction of Dominique Vidalenc . During this time the skull of a hyaenodont could already be found, which is placed to Cynohyaenodon and thus in the closer relationship of the Hyaenodontidae . The Kerberos finds came to light in 1981. They consist of the skull, the lower jaw and parts of the lower hind leg. Due to the fauna composition, the site dates to the end of the Middle Eocene with absolute age values of 40 to 38 million years. This means that Kerberos is one of the oldest Hyainai tourids in Europe, alongside Paroxyaena .

Paleobiology

With the stated body weight of around 140 kg, Kerberos can be regarded as one of the largest terrestrial predators of its time. At the same time, the genus represents one of the largest known representatives of the Hyainailouridae, but it did not reach the enormous proportions of the genealogically much younger Megistotherium , which weighed around 800 kg. The complete skull enables the chewing apparatus to be reconstructed. The masticatory muscles were strongly developed, the striking masseteric fossa on the lower jaw refers to several massive muscles such as the temporalis muscle , the masseter muscle and the zygomaticomandibularis muscle . As is common in today's predators, the temporalis muscle complex dominated over the masseter muscle complex. The former started at the crest, the latter at the zygomatic arch. The construction of the crown process with the deep anterior furrow served as a further starting point for the muscle fibers of the temporalis or temple muscle and thus led to greater biting force. The medial pterygoid muscle , on the other hand, was less involved in the closure of the lower jaw, as indicated by the forwardly displaced choans and the rather small angular process on the lower jaw; Both of these circumstances left only small areas of attachment for the muscle. This is what distinguishes Kerberos from some of the younger Hyainailouirids with their stronger wing muscles. Due to the very large mastoid process, a massive digastric muscle could be assumed, which also controls the movement of the lower jaw. However, since other muscles for the cervical spine are also anchored here, this is not clear. The entire configuration of the chewing apparatus in Kerberos advocates vigorous upward and downward movements of the lower jaw with great force development in the molar area while at the same time reducing lateral movements. The molars specialize in a cutting function rather than perforating or breaking. This is indicated by the reduced metaconid (perforating) or the shortened talonid and the smaller protoconus (breaking). These characteristics give the dentition of Kerberos hypercarnivore properties (today's hypercarnivores eat at least 70% of carnal food). The premolars show a high degree of use based on the traces of abrasion. Probably Kerberos, like today's hyenas , was able to bite larger bones with the premolar teeth, in contrast to the wolf-like and jackal-like , which do this with the rearmost molars. The somewhat longer snout compared to Megistotherium, in turn, meant that the canines were less effective in Kerberos . The animals therefore probably occupied the niche of the large scavengers. However, it cannot be ruled out that they were also capable of active hunting. Today's predators weighing around 21 kg or more mainly kill prey of their own size or more. For Kerberos with its enormous dimensions, larger ungulates such as Choeropotamus or odd ungulates such as Lophiodon would come into consideration as preferred prey. In general, Kerberos can be regarded as a top predator of the Middle Eocene.

The few long bones in turn give an insight into the movement of Kerberos . The tibia and fibula are not fused together. The large heads for articulation with the shin or heel bone indicate a well-movable lower leg section, such as occurs in bears and cats and is suitable for locomotion in rocky terrain. The short heel bone, the flattened head of the ankle bone as well as its short neck and the short metatarsal bones in turn indicate a plantigrade gait. Furthermore, the downward-facing sustentaculum tali on the heel bone and the only slightly indented joint role of the ankle bone speak for a mainly terrestrial locomotion. Some features, such as shallow dimples on the ankle joint, indicate a possible ability to climb. However, this may be an ancient feature, since original hyaenodonts were adapted to tree climbing. According to this, Kerberos shows itself to be a sole-length terrestrial animal that was probably not capable of running fast. In this aspect, the animals differ from today's hyenas, despite their sometimes scavenging diet, which have adaptations to rapid locomotion.

Systematics

|

Internal systematics of the Hyainailouridae according to Borths and Stevens 2019

|

Kerberos is a genus from the extinct family of the Hyainailouridae , which in turn belong to the also extinct order of the Hyaenodonta . The Hyaenodonta once formed part of the Creodonta , sometimes somewhat misleadingly also referred to as "primitive predators ", which were regarded as the sister group of today's carnivores (Carnivora) within the superordinate group of the Ferae . Since the Creodonta turned out to be a non-self-contained group, they were split up into the Hyaenodonta and the Oxyaenodonta . A characteristic feature of both groups is the crushing shears , which are shifted further back in the teeth compared to the predators . In the hyaenodonts, the second upper and third lower molars are usually involved. The hyaenodonts first appeared in the Middle Paleocene around 60 million years ago and disappeared again in the course of the Middle Miocene around 9-10 million years ago. The Para- and Metaconus, which have grown together to form the amphiconus, are characteristic of the Hyainailouridae. The former dominates the latter, a situation that is exactly the opposite of the related Hyaenodontidae . Within the Hyainailouridae, Kerberos is placed in the subfamily of the Hyainailourinae . In these, the degree of fusion of the para and metaconus is very advanced. Close relatives of the genus are for example Hemipsalodon , Pterodon and Metapterodon . The latter has so far only been proven in Africa, while evidence for the former is only available from North America.

The genus Kerberos was scientifically described for the first time in 2015 by a research team led by Floréal Solé . The finds from Montespieu near Lautrec in southern France served as the basis. The holotype (copy number MNHN .F.EBA 517) represents an almost complete skull with the largely complete rear set of teeth and some front teeth. The genus is named after the hellhound Kerberos , the multi-headed guardian of the underworld in Greek mythology . Together with the genus, the team set up the species K. langebadreae . The specific epithet was chosen in honor of Brigitte Lange-Badré , who dealt intensively with the Eocene predators.

literature

- Floréal Solé, Eli Amson, Matthew Borths, Dominique Vidalenc, Michael Morlo and Katharina Bastl: A New Large Hyainailourine from the Bartonian of Europe and Its Bearings on the Evolution and Ecology of Massive Hyaenodonts (Mammalia). PLoS ONE 10 (9), 2015, p. E0135698, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0135698

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Floréal Solé, Eli Amson, Matthew Borths, Dominique Vidalenc, Michael Morlo and Katharina Bastl: A New Large Hyainailourine from the Bartonian of Europe and Its Bearings on the Evolution and Ecology of Massive Hyaenodonts (Mammalia ). PLoS ONE 10 (9), 2015, p. E0135698, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0135698

- ↑ a b Matthew R. Borths, Patricia A. Holroyd and Erik R. Seiffert: Hyainailourine and teratodontine cranial material from the late Eocene of Egypt and the application of parsimony and Bayesian methods to the phylogeny and biogeography of Hyaenodonta (Placentalia, Mammalia). PeerJ 4, 2016, p. E2639, doi: 10.7717 / peerj.2639

- ^ Hans Georg Stehlin: Sur les mammifères des sables Bartoniens du Castrais. Bulletin de la Société géologique de France 4, 1904, pp. 445–475 ( [1] )

- ^ Brigitte Lange-Badré: Cynohyaenodon lautricensis nov. sp. (Creodonta, Mammalia) et les Cynohyaenodon européens. Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire Naturelle de Toulouse 114, 1978, pp. 472–483 ( [2] )

- ↑ Floréal Solé and Sandrine Ladevèze: Evolution of the hypercarnivorous dentition in mammals (Metatheria, Eutheria) and its bearing on the development of tribosphenic molars. Evolution & Development 19 (2), 2017, pp. 56-68

- ↑ Matthew R. Borths and Nancy J. Stevens . Simbakubwa kutokaafrika, gen et sp. nov. (Hyainailourinae, Hyaenodonta, 'Creodonta,' Mammalia), a gigantic carnivore from the earliest Miocene of Kenya. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 2019, p. E1570222, doi: 10.1080 / 02724634.2019.1570222

- ↑ Kenneth D. Rose: The beginning of the age of mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2006, pp. 1–431 (pp. 122–126)

- ↑ Michael Morlo, Gregg Gunnell, and P. David Polly: What, if not nothing, is a creodont? Phylogeny and classification of Hyaenodontida and other former creodonts. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (3 suppl), 2009, p. 152A

- ↑ Floréal Solé: New proviverrine genus from the Early Eocene of Europe and the first phylogeny of Late Paleocene-Middle Eocene hyaenodontidans (Mammalia). Journal of Systematic Paleontology 11, 2013, pp. 375-398

- ↑ Floréal Solé and Bastien Mennecart: A large hyaenodont from the Lutetian of Switzerland expands the body mass range of the European mammalian predators during the Eocene. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 64, 2019, doi: 10.4202 / app.00581.2018