Klaus-Andreas Moering

Klaus-Andreas Moering (born December 10, 1915 in Breslau ; † March 17, 1945 in Glatz ) was a German expressionist painter .

Parents and youth

Klaus-Andreas Moering was born as the son of Ernst (1886–1973) and Isa Moering, b. von Koskull (1881–1957), born. He had a younger brother Ivo Moering (1917–1984). The influence of the parental home was enlightened and liberal. The father was initially a preacher at the Queen Luise Memorial Church in Breslau and from 1927 director of the municipal public library in the Silesian capital. The mother came from a noble family in Courland. In 1933 the father, who was a member of the German Democratic Party , had to quit work under pressure from the National Socialists and was locked up in a concentration camp for a few weeks .

Artistic beginnings

From the age of 15 or 16, i.e. from around 1930, Klaus-Andreas Moering received private drawing lessons from the artist Ludwig Peter Kowalski , who at the time was the head of the study department at the Wroclaw School of Applied Arts. In 1935 Moering passed the Abitur at the Humanistic Gymnasium in Breslau. Then he was called up for the mandatory 6 months for the Reich Labor Service . After he had decided to become a painter, he then applied to the Wroclaw School of Applied Arts. But he was rejected, although his father's political stance and the fact that his teacher Kowalski had since been removed from office for political reasons may have played a role. So he initially enrolled in German studies at the University of Wroclaw . At the beginning of 1936, the then 20-year-old moved to Berlin to study art there. At the request of his father, who insisted on a specific vocational training as an art teacher, he enrolled at the State University for Art Education in the summer semester of 1936 . In that year he also met Elisabeth Dorothea "Elle" Nay, a cousin of the painter Ernst Wilhelm Nay , whom he married on May 20, 1938. The children of the marriage were Andrea Müller-Osten b. Moering (* 1938) and Michael Moering (1942–1986).

Study time

At the 1933 already conformist Berlin University studied Moring in the class of Konrad von Kardorff . Moering felt uncomfortable at school because the Expressionist painters he admired were considered ostracized. In 1937 he wrote: “Up until now there were always only those in the classes who considered you crazy to use the name Nolde z. B. only took it in the mouth. In doing so, they cannot understand a line that has so much life and expression, let alone imitate it… ” In the summer of 1937, Moering was enrolled in Alfred Particle's class as part of an“ Eastern semester ”at the State Masters' Ateliers in Königsberg . Here he got to know fellow students from other classes who, like him, used the artists vilified as “degenerate” as models: “Some have originals by Schmidt-Rottluff , Pechstein etc. and good reproductions by Nolde, Mueller , Kokoschka , Kirchner …” Aus The first surviving works by Moering date from the Königsberg period, showing the influence of Schmidt-Rottluff in their formal reduction and emphasis on the contour line. The first landscape watercolors were created during an excursion by the university to Weißenburg (East Prussia) .

Encounters with Ernst Wilhelm Nay and the exhibition “Degenerate Art” in Berlin

Through his wife Elle, Moering came into contact in autumn 1937 with the painter Ernst Wilhelm Nay , who had been banned from exhibiting . This gave him a perspective on how the expressionist painting of the 1910s and 1920s that Moering admired could be further developed: “The man really goes further and creates his own laws. A painter through and through, he uses color and space and light - which all Expressionists do not have - to create light, not impressionistically. And for him the space is a perspective illusion - he doesn't cut a hole in the canvas - but the surface is completely preserved. ” Moering admired Nay's freedom with which he detached himself from the reproduction of representational visual experiences. For the second key event of multiple visiting the abusive exhibition "was for Moring Degenerate Art " at the Berlin station in the House of Art at the Reichstag in spring and summer 1938. Moring conceived the exhibition as a final opportunity to a large number of works of classic modern art in depth to study. There he was particularly enthusiastic about the painters of the bridge, especially Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Otto Mueller, but also Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel and Paul Klee . The self-confident and judgmental Moering was more critical of Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann and above all Karl Hofer , whose works he rejected. He recorded his impressions in letters and diary notes and noted the works he saw. His related notes are an important source for the Berlin station of the exhibition. After he had completed his studies in art education in 1939, his career as a teacher for art education and German at two Berlin schools was very busy until March 1942.

Artistic development in the years 1938–1944

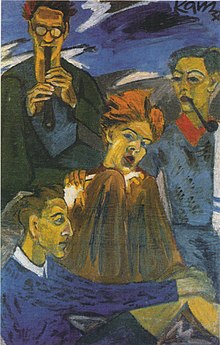

Summer stays in his in-laws' holiday homes in Poberow on the Baltic Sea were of great importance for Moering's artistic development . Together with his artist friends Joachim Albrecht and Hans Hermann Steffens and his wife Elle, he stayed there for the first time in 1938. Looking back in 1986, Steffens reported on an atmosphere of joint work that was reminiscent of the stays of the “ Brücke ” painters at the Moritzburg ponds : “The days are full for us. I don't think we've ever been as exuberant as this summer. Full of life, overflowing with everything we do. The work is discussed and criticized. We try to assert ourselves against anything that could destroy the values we believe in. ” In that summer of 1938 he created the large-format oil painting“ Steffens, Albrecht, Elle and I on the beach ”, which Moering wrote as his“ doctoral thesis ”. should have designated. Increasingly he broke away from the natural model and worked more abstractly and geometrically. The choice of colors also increasingly followed immanent criteria and not the portrayal of reality, as the motif of the blue-spotted “Cows I” from 1938 shows. While the landscapes of that time were still characterized by strong contours and angular shapes, his style became more and more free and lighter from around 1941. The landscapes now showed - often based on a calm central motif such as the holiday cabin or a single tree - a world diverging in swirling, quick brushstrokes. In addition to landscape watercolors, portraits were his second focus, with his wife Elle and himself being the most common motifs. While his first self-portrait from 1937 had shown him self-confidently in a style reminiscent of the New Objectivity, the motif subsequently became an expression of his painterly development, but also of his increasing doubts as to whether he would succeed under the given circumstances as desired to be able to develop. A final self-confident manifesto is the watercolor “Self-Portrait I” from 1942, in which he demonstrated his continued loyalty to Expressionist painting with strong color contrasts. The other self-portraits bear witness to the increasing tension and gloom that gripped the artist after he was called up. On his last home leave in December 1944, he painted himself in uniform, hugged by his wife, in a painting with the ominous title Farewell .

Military service and death

In April 1942 Moering was drafted into the Wehrmacht. After basic training as an artillery soldier in Lissa , he was sent to the Eastern Front. In June 1942 the company commander suggested to him that he should become an officer candidate: “Of course I refused [...] the same thing everywhere: outward appearances, tinsel, material advantages. [...] You can't serve two gentlemen and for me it's painting. " Since July at the front, he wrote in August 1942: " I'm not a soldier, I will never become one - all this dead time and senseless activity. “ Only interrupted by short vacations from the front in spring 1943, in summer and in December 1944, Moering served on the eastern front in the area of Army Group Center . He participated in the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht from Russia to his Silesian homeland. He fell here shortly before the end of the war - not far from Glatz on March 17, 1945. From the war years 1942 to 1945, 470 letters from Klaus-Andreas Moering have survived, showing him as an attentive observer. The main addressees were his wife Elle, cousin Ruth Moering (letters not received) and his artistic mentor and friend Ernst-Wilhelm Nay.

Fate of the work

At the end of the war, almost all of Moering's works were in the rectory in Bad Muskau , where his wife lived with their two children. Only through the courageous intervention of a neighbor could they be saved from being burned by Soviet soldiers after they had fled, and so came back into the possession of their descendants. As a result, individual works have become public property. A total of around 80 works by Klaus-Andreas Moering have survived. Some of them are in public ownership: 26 watercolors and drawings as well as 2 oil paintings are in the Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg as a foundation of the daughter Andrea Müller-Osten. 5 watercolors and 1 drawing are in the collection of the Berlinische Galerie, 2 watercolors and 2 drawings are in the graphic collection of the Hessen Kassel Museum Landscape. Further works by the artist can be found in private ownership. Around 700 letters (originals and copies) as well as other documents, the diary and photographs of Klaus-Andreas Moering can be found in the German Art Archive in Nuremberg.

reception

Research into Moering's work was initially pursued by his son Michael. Around 1985 he compiled the sources on family, friends, studies, artistic work and military service and transcribed his father's letters. It was not until 1991 that the first detailed appraisal of the artist by the art historian Reglindis Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn appeared - a result of a master's thesis submitted in 1987 at the TU Berlin and based on the extensive preparatory work by Michael Moering. After the foundation of numerous works Moerings in the Art Forum East German Gallery in Regensburg in November 2011, these were presented in an exhibition, 2014. The accompanying catalog contains an essay by the graphics collection manager, Agnes Matthias, on Moering's work. In 2019, the art historian Hans Georg Hiller von Gaertringen gave a lecture in Berlin for the support group of the Brücke Museum on Moering's visit and notes on the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in 1938. The writer Walter Kempowski took a total of 13 letters from Moering in January and February 1943 and 4 letters from February 1945 in his literary collage " Das Echolot ". In a letter to Moering's daughter Andrea in 1993, Kempowski wrote: “Your father's descriptions are so vivid - how could it be any other way with a painter - and the spirit, if I may put it so, so incredibly sympathetic that one cannot withhold them from readers should. ” Kempowski intended to publish further letters from Moering from 1942 to 1945 in a follow-up to“ Echolot ”with the title“ Ortlinien ”, but he did not complete this project.

rating

Klaus-Andreas Moering's artistic development was impaired by the National Socialist rule in three ways: First, due to the co-ordination of the art colleges and the expulsion of the main protagonists of modernism in the 1920s, it was hardly possible for him to find teachers who corresponded to his modern inclinations. The professors and lecturers with whom he studied instead saw his art as “dangerous” or even “degenerate”. Nobody recognized and appreciated his talent in a way that he would have done before 1933 and after 1945. Second, almost three years of military service prevented him from practicing painting and drawing. After all, his untimely death as a soldier prevented the further development of his talent. Moering thus shares the fate of many painters of the “missing generation” of artists whose careers ended after 1933 or were unable to develop at all.

Posthumous exhibitions

- 1960 Atelier Christa Moering , Wiesbaden

- 1960 Kunstkabinett Hanna Bekker vom Rath , Frankfurt am Main

- 1974 State Art Collections, Kassel

- 1986 Atelier Christa Moering, Wiesbaden

- 1987 Stiftung Kulturwerk Schlesien , Würzburg

- 2014 Art Forum Ostdeutsche Galerie, Regensburg

literature

- Michael Moering: A big, hopeful glow. The painter Klaus-Andreas Moering , in: Schlesischer Kulturspiegel 1 (1986), p. 1

- Reglindis Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn: The painter Klaus-Andreas Moering , in: Hartmut Horn (ed.): Klaus-Andreas Moering 1915–1945. A painter of the lost generation from the time of National Socialism , Essen 1991, pp. 7-63 (revised and abridged version of an art-historical master's thesis, TU Berlin, 1987)

- Rainer Zimmermann: Expressive Realism , Munich 1994, p. 417

- Johanna Brade: Between bohemian artists and the economic crisis. Otto Müller as professor at the Breslau Academy 1919–1930 , Görlitz 2004, p. 19

- Helmut Arntzen: From the German present. German sentences from the 20th century , in: On the State of the Nation 15 (2007)

- Agnes Matthias: "As an artist everything is unknown" - On the work of Klaus-Andreas Moering , in: Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg (ed.): " As an artist everything is unknown" - The Klaus-Andreas Moering Foundation , Regensburg 2014, p. 8-21

Web links

- Literature by and about Klaus-Andreas Moering in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 11

- ^ Letter to Elle Nay, April 25, 1937, quoted in according to Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 16

- ^ Letter to Elle Nay, April 25, 1937, quoted in according to Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 17

- ^ Letter to Hans Hermann Steffens dated March 2, 1938, cited above. according to Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 30f.

- ^ "Rückerinnerung" by Hans-Hermann Steffens, March 1986, cited above. according to Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 39

- ↑ Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 39, there without reference to the source

- ^ Letter of June 5, 1942, quoted in according to Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 52

- ^ Letter of August 18, 1942, quoted in according to Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 52

- ^ Letter from Walter Kempowski to Andrea Müller-Osten dated June 30, 1993, Andrea Müller-Osten private archive

- ^ Letter from Walter Kempowski to Andrea Müller-Osten dated August 10, 1993, Andrea Müller-Osten private archive

- ↑ According to the lecturer for "Applied Work Techniques" at the Berlin University, Charlotte Jäckel, who viewed Moering's thesis on the work teacher examination, a rocking horse, as "degenerate". Schulte-Tigges-Dettbarn 1991, p. 15f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Moering, Klaus-Andreas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 10, 1915 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wroclaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 17, 1945 |

| Place of death | Bald |