Koira Tagui (Niamey)

|

Neighborhood Koira Tagui |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 13 ° 35 ' N , 2 ° 7' E |

| Basic data | |

| Country | Niger |

| Niamey | |

| Arrondissement | Niamey II |

| ISO 3166-2 | NE-8 |

| Residents | 35,784 (2012) |

Koira Tagui (also: Foulan Koira ) is a district ( French : quartier ) in the Arrondissement Niamey II of the city of Niamey in Niger .

geography

Koira Tagui is located on the northern edge of the urban area of Niamey, east of National Road 24 leading to Ouallam . The surrounding neighborhoods are Dan Zama Koira in the east, North Faisceau in the south, Francophonie in the southwest and Tchangarey II in the northwest. The closest village in the rural parish is Bossey Bongou Château in the northeast. Like all of the north of the city, Koira Tagui is located in a plateau with a layer of sand less than 2.5 meters deep, which means that only limited infiltration is possible.

Alternative spellings of the name are Koiratagui , Koira Tédji , Koira Tegui , Koiratégui , Kouara Tagui , Kouaratagui , Kouara Tegui , Kouaratégui and Kwaratégui or Foulani Kouara , Foulan-Koira , Foulankoira , Foulankouara , Foulan Kouara , Foulankwara , Foulan-Kwara and Foulan Kwara .

history

The place name comes from the Songhai-Zarma language : Koira Tagui means "new village" and Foulan Koira means "village of the Fulbe ".

As a result of the famine in Niger in 1931, an estimated 22,000 to 23,000 people moved to Niamey, where the French colonial administration distributed food free of charge. This migration formed the basis of the new settlements Koira Tagui and Deyzeibon . Koira Tagui had several different locations in the 20th century. The changes were relatively easy because the settlement consisted of straw huts. In the 1930s the settlement was in the city center and, along with Gawèye , Kalley , Maourey and Zongo, was one of the five districts that made up Niamey, which was founded in the early 20th century. Fulbe blacksmiths and Hausa cattle breeders lived in what was then Koira Tagui. The district was moved for the first time in 1931 to make way for the Palace of Justice. There it was replaced by the Lyceum in 1933, then by the radio station in 1936. From 1938 Koira Tagui was on the northern outskirts behind the dry valley Gounti Yéna , where it remained for a long time. The drought years of 1984 and 1985 saw strong population growth when Fulani refugees, who had initially settled in the city center, were driven here to reduce the risk of fire in the city center. In Koira Tagui they found pastures and were able to raise cattle and farm crops.

At the end of the 1980s, Koira Tagui reached its current location in the north after the population had been evicted from the previous to make way for the General Seyni Kountché Stadium, which was completed in 1989 . This time the land was parceled out and sold by the state to the residents. In addition, special zones for the blind and lepers have been created here. These gained the attention of international aid organizations that had a strong presence in Koira Tagui. This, in turn, led to the district's reputation for hosting a particularly large number of beggars. At the beginning of the 21st century, Koira Tagui had on the one hand developed the character of a dormitory city, as living in the city center had become too expensive, on the other hand it became a transit station for migrants from the Ouallam department who wanted to settle in the capital. Koira Tagui is one of the most dangerous areas of Niamey in terms of robbery and theft. In 2007, the district was one of the venues for the first edition of the Pripalo open-air cultural festival under the direction of Achirou Wagé .

population

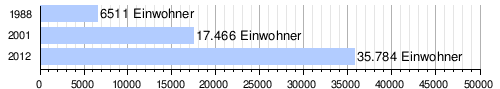

At the 2012 census, Koira Tagui had 35,784 residents who lived in 5,563 households. At the 2001 census, the population was 17,466 in 2,804 households, and at the 1988 census, the population was 6,511 in 1,106 households.

Infrastructure

In Koira Tagui there is a state health center (Center de Santé Intégré) , which was established in 1986. The public primary school Ecole primaire de Koira Tagui was founded in 1992. The secondary school Collège d'enseignement général de Koira Tagui (CEG Koira Tagui) has existed since 2004.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b National Repertoire des Localités (ReNaLoc). (RAR) Institut National de la Statistique de la République du Niger, July 2014, p. 716 , accessed on 7 August 2015 (French).

- ↑ Hamadou Issaka, Dominique Badariotti: Les inondations à Niamey, enjeux autour d'un phenomène complexe . In: Cahiers d'Outre-Mer . No. 263 , September 2013, p. 383–384 ( journals.openedition.org [accessed April 21, 2019]).

- ↑ Bachirou Ayouba Tinni: Migrant malien blanchisseurs à Niamey: pratiques migratoires et réseaux d'insertion . Mémoire. Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, Niamey 2015, Chapitre 2.2 Les facteurs de la consécration de la ville de Niamey ( memoireonline.com [accessed May 10, 2019]).

- ↑ Hamadou Issaka: L'habitat informel dans les villes d'Afrique subsaharienne francophone à travers l'exemple de Niamey (Niger) . Thesis. Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour, Pau 2007, Chapitre VI Le squattage à Niamey: question urbaine ou question sociale? ( memoireonline.com [accessed April 21, 2019]).

- ^ A b Apollinaire Tini: La gestion des déchets solid ménagers à Niamey au Niger: essai pour une stratégie de gestion durable . Thèse de doctorat. Institut National des Sciences Appliquées de Lyon, Lyon 2003, p. 77–78 ( theses.insa-lyon.fr [PDF; accessed May 1, 2019]).

- ↑ Kokou Henri Motcho: Niamey, Garin captan Salma ou l'histoire du peuplement de la ville de Niamey . In: Jérôme Aloko-N'Guessan, Amadou Diallo, Kokou Henri Motcho (eds.): Villes et organization de l'espace en Afrique . Karthala, Paris 2010, ISBN 978-2-8111-0339-2 , pp. 28 .

- ^ A b Patrick Gilliard: L'extrême pauvreté au Niger. Mendier ou mourir? Karthala, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-84586-629-1 , p. 148-149 .

- ^ Patrick Gilliard: L'extrême pauvreté au Niger. Mendier ou mourir? Karthala, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-84586-629-1 , p. 170 .

- ^ Hilary B. Hungerford: Water, Cities, and Bodies: A Relational Understanding of Niamey, Niger . Dissertation. University of Kansas, Lawrence 2012, pp. 113 ( kuscholarworks.ku.edu [PDF; accessed on May 10, 2019]).

- ↑ Abdouramane Seydou: Délinquance et governance urbaine à Niamey. Institut de Recherche en Sciences Humaines, Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, July 27, 2018, accessed on April 19, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Ibrahim A. Tikiré: Lancement du festival Pripalo. In: Niger Diaspora. July 19, 2007, accessed October 23, 2019 (French).

- ^ Répertoire National des Communes (RENACOM). (RAR) (No longer available online.) Institut National de la Statistique de la République du Niger, archived from the original on January 9, 2017 ; Retrieved November 8, 2010 (French). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Recensement Général de la Population 1988: Répertoire National des Villages du Niger . Bureau Central de Recensement, Ministère du Plan, République du Niger, Niamey March 1991, p. 222 ( web.archive.org [PDF; accessed May 4, 2019]).

- ^ Hassane Daouda: Visite du ministre de la Santé Publique dans des unités de soins de trois arrondissements de la région de Niamey: Recensement desproblemèmes des formations sanitaires au menu de la visite. In: Niger Diaspora. November 1, 2011, accessed May 27, 2019 (French).

- ↑ Daniel Barreteau, Ali Daouda: Systèmes éducatifs et multilinguisme au Niger. Results scolaires, double flux . Orstom / Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, Paris / Niamey 1997, ISBN 2-7099-1365-8 , p. 85 ( horizon.documentation.ird.fr [PDF; accessed May 29, 2019]).

- ↑ Rapport de l'étude preparatoire pour le projet de construction des établissements d'enseignement secondaire au Niger. (PDF) Chapitre 2. Agence japonaise de coopération internationale (JICA), April 2013, p. 15 , accessed on June 6, 2019 (French).