Kulak

The term Kulak ( Russian кулак , "Faust") was a term used in Russian for relatively wealthy farmers since the 19th century . At the latest after the turn of the century, the term acquired a pejorative (pejorative) character. After the October Revolution of 1917 and during the forced collectivization of agriculture from 1928 to 1933 under Josef Stalin , the meaning of "Kulak" in which it was propaganda of the Bolsheviks more and more extended to all self-employed farmers. These people and their relatives were deported to labor camps or shot as class enemies as part of the deculakization between 1929 and 1932 . A few years later, the kulaks were during the Great Terror shot again hundreds of thousands or deported, in particular by means of the NKVD command No. 00,447th - the NKVD -Jargon also Kulakenoperation called.

Categorization of the rural population

A villager in Tsarist Russia or the Soviet Union was able to carry out several activities in the course of the year: a farmer during the growing season, migrant workers or homework in winter , trading or helping a neighbor as a day laborer with the harvest. Despite difficulties in finding any meaningful criteria for a socio-economic classification, Marxist economists and statisticians made a classification within village society. The standardized nomenclature differentiated the batraki (landless workers), the bednjaki (farmers with plots of land that did not produce enough yield) and the serednjaki (middle farmers). The so-called kulaks were at the top of this socio-economic classification .

From the perspective of contemporary Soviet Marxists who dealt with the conditions in the countryside, the kulak was considered to be the holder of the greatest economic power. The term had a derogatory meaning and was intended to mark the " exploiter " in the village. Which criterion made a farmer a kulak , however, was always unclear, the definition of the term kulak was "so vague that it fit almost everyone". For example, it was conceivable that equipment and draft horses could be rented or that day laborers were employed - phenomena that in real village life by no means only applied to the kulaks . Half a million farms at most belonged to this category; this corresponded to a number of about three million people or two percent of all households.

The majority of the farmers were so-called middle farmers (approx. 75%), who were often referred to as kulak servants. They were accused of hoarding or hiding grain - measures to which the high compulsory levies and taxation of individual farmers led. The industrial development of the country was carried out by squeezing almost all farmers as much as possible. Despite the shortage of grain, the Soviet Union exported the grain in order to be able to buy machines and tools (so-called starvation exports). So the peasants had to pay a large part of the social costs of industrializing the Soviet Union . The famine of 1932/33 that was largely triggered by collectivization and deculakization , especially the Holodomor in Ukraine, cost between 5.5 and 6.5 according to historians' estimates (as a result of starvation, the decline in the birth rate, illnesses, etc.) Millions of people's lives.

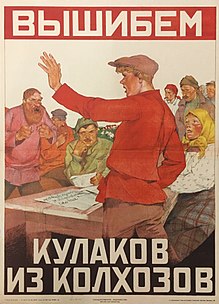

propaganda

During the Russian Civil War , farmers fought against increasing grain requisitions . Lenin interpreted this as "kulak uprisings" and suspected an organizational connection with non-Bolshevik socialist parties and foreign capitalists . In August 1918 he demanded that they be crushed with extreme severity:

“These leeches sucked the blood of the working people and became the richer the more the workers in the cities and factories were starving. These vampires brought and are taking over the land of the landowners , forcing the poor peasants into debt bondage over and over again . Merciless war against these kulaks! Death to them! Hatred and contempt for the defending parties: the right social revolutionaries , the Mensheviks and today's left social revolutionaries ! With an iron fist, the workers have to put down the uprisings of the kulaks who form an alliance with foreign capitalists against the working people of their country. "

As part of the ideological campaign against alleged capitalists, the kulaks were soon assigned to “lower” and “half-kulaks” from the group of middle peasants. The middle peasants made up the bulk of the village population and produced most of the grain. Ultimately, most of the middle peasants were also assigned to the kulaks. In addition, there were no precise criteria for assigning the name Kulak. So was z. B. on the one hand, the rental of work equipment or cattle is seen as crucial. On the other hand, there were studies that saw the employment of wage laborers as a decisive criterion. The difference between the kulaks and the middle peasants was only of degree and was made arbitrarily by the Bolsheviks. "In practice, the state decided who was and who was not the kulak." A local party leader said: "At plenary meetings of the village soviet we create kulaks as we see fit."

When the deculakization, i.e. the state campaign against alleged or real kulaks, became more and more radical, at the height of collectivization in 1932 even minor agricultural property such as a cow or the employment of day laborers or servants was considered kulaks and led to coercive measures: first higher taxes, then expropriation , finally deportation to deserted areas or to the gulag . If there were signs of resistance to the coercive measures of the Bolsheviks, the execution of the victim was scheduled. The family members of those affected and even so-called kulak henchmen, the Podkulachniki , were often persecuted. This meant that every day laborer could also be deported as a "kulak henchman".

With his slogan, formulated publicly at the end of 1929, of the "liquidation of the kulaks as a class", Stalin called for war against the peasants.

reception

A positive evaluation of the measures against the "kulaks" is contained in the early work of Michail Scholochow Neuland unterm Pflug from 1932. In later Soviet novels the fate of the "kulaks" appears again and plays the role of a collective trauma. B. with Tschingis Aitmatow : One day longer than life (1980) and with Yevgeny Yevtushenko : Where the berries ripen (1981).

The boy Pawlik Morosow , who denounced his own father as a kulak and was then allegedly murdered by relatives, was presented as a role model and hero to the socialist youth for a long time. Lenin pioneers were asked to use his example to monitor their parents themselves and to report suspicious facts to the authorities.

literature

- Anne Applebaum : Red Hunger - Stalin's War against Ukraine . Translated by Martin Richter. Siedler, Munich 2019. ISBN 978-3-8275-0052-6 .

- Robert Conquest : The Harvest of Sorrow. Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1986, ISBN 0-19-505180-7 (English, German: Harvest of Death . Stalin's Holocaust in Ukraine 1929–1933, Ullstein TB 33 138, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-548- 33138-6 ).

- Alexander Heinert: The enemy image of the Kulak. The political and social crux of 1925–1930. In: Silke Satjukow , Rainer Gries (ed.): Our enemies. Constructions of the other in socialism. Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 978-3-937209-80-7 , pp. 363-386.

- Dimitri A. Volkogonow : Lenin. Utopia and terror. (Translated from Russian by Markus Schweisthal). Econ, Düsseldorf / Vienna / New York / Moscow 1996, ISBN 3-430-19828-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Translation on dict.cc

- ↑ a b Manfred Hildermeier , History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991 , CH Beck, Munich 1998, p. 1184. ( online )

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier , History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991 , CH Beck, Munich 1998, p. 292. ( online )

- ^ Anne Applebaum : The Gulag . Translated from the English by Frank Wolf. Siedler, Munich 2003, p. 87, ISBN 3-88680-642-1 .

- ↑ Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991 , p. 292; Heinert, enemy, kulak ' , pp 367-371.

- ↑ Hildermeier, History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991 , p. 393.

- ↑ The information given by various historians on the number of victims varies greatly; the number given here appears to be sufficiently objective. For an evaluation see Davies / Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933, p. 401.

- ↑ Vladimir I. Lenin: Comrades, workers! On to the last decisive fight! , quoted by Klaus-Georg Riegel: Marxism-Lenism as a "political religion". In: Gerhard Besier , Hermann Lübbe (Hrsg.): Political religion and religious policy. Between totalitarianism and civil liberty . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, p. 27.

- ↑ Manfred Hildermeier , History of the Soviet Union 1917–1991 , CH Beck, Munich 1998, p. 290 ff. ( Online )

- ↑ Alexander Heinert, Das Feindbild Kulak. The political-social crux 1925–1930 , in: Silke Satjukow and Rainer Gries, (eds.), Our enemies. Constructions of the Other in Socialism , Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2004, p. 373

- ↑ Timothy Snyder : Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin , CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62184-0 , p. 47.

- ↑ Quoted from Timothy Snyder: Bloodlands. Europe between Hitler and Stalin , CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62184-0 , p. 47.

- ↑ Hellmuth Vensky: Stalin's Crimes of the Century , in: Die Zeit online, February 1, 2010.

- ↑ See on the Stalinist call for the “liquidation of the kulaks” and “smashing our class enemies in the countryside” and the like. a. Oxana Stuppo: The enemy image as a central element of communication in late Stalinism. Berlin 2007, p. 33; Ulf Brunnbauer , Michael G. Esch, Holm Sundhaussen: Power of definition, utopia, retaliation: “ethnic cleansing” , 2006, p. 124. For the “war against the kulaks” see below. a. Leonid Luks : History of Russia and the Soviet Union. From Lenin to Jelzin , Pustet, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7917-1687-5 , p. 255; Nicolas Werth : A state against its people. Violence, Oppression and Terror in the Soviet Union. In: Stéphane Courtois , Nicolas Werth, Jean-Louis Panné, Andrzej Paczkowski, Karel Bartosek, Jean-Louis Margolin. Collaboration: Rémi Kauffer, Pierre Rigoulot, Pascal Fontaine, Yves Santamaria, Sylvain Boulouque: The Black Book of Communism . Oppression, crime and terror. With a chapter "The processing of the GDR" by Joachim Gauck and Ehrhard Neubert. Translated from the French by Irmela Arnsperger, Bertold Galli, Enrico Heinemann, Ursel Schäfer, Karin Schulte-Bersch, Thomas Woltermann. Piper. Munich / Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-492-04053-5 , pp. 51–295 and 898–911, here p. 165; Jörg Baberowski : The red terror. The history of Stalinism. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-421-05486-X , p. 122. Robert Gellately writes: "That was a declaration of war on the village society" (Robert Gellately: Lenin, Stalin and Hitler: three dictators, the Europe into the abyss . Bergisch Gladbach 2009, p. 237).