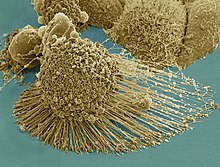

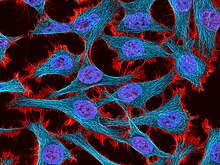

HeLa cells

HeLa cells (HeLa line; HeLa cell strain) are human epithelial cells of a cervical carcinoma (cervical cancer) and the first human cells from which a permanent cell line was established. The cells were infected with human papillomavirus 18 (HPV18). The genetic defect has now been clarified: the cells had degenerated into tumor cells due to a viral protein (oncogene E6 or E7), which inactivates the p53 tumor suppressor, and a mutation in the human leukocyte antigen ( HLA ) of the supergene family on chromosome 6 .

Origin of cells

The HeLa cells were obtained from a tissue sample from a cervical tumor of the Afro-American patient Henrietta Lacks (born August 1, 1920 in Roanoke (Virginia), † October 4, 1951 in Baltimore (Maryland)) (incorrectly also called Henrietta Lakes, Helen Lane or Helen Larson named) established.

After the birth of her fifth child, Henrietta Lacks suffered from profuse irregular abdominal bleeding. Her family doctor referred her to the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for an examination , the only hospital in the wider area in the 1950s that treated black people free of charge. There, the gynecologist Howard W. Jones found a 2-3 cm large lump on her cervix (cervix). Jones removed a tissue sample from the tumor, which microscopic examination diagnosed squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, which tumor was later identified histopathologically as an adenocarcinoma .

Lacks was treated with internal and external radiation. On February 9, 1951, Jones obtained additional tissue samples from the cervix during one of these radiation sessions. He passed these samples on to George Otto Gey, who was working at the Johns Hopkins Hospital to create a potentially immortal cell line. From these cells the actually potentially immortal HeLa cell line emerged.

On August 8, 1951, Lacks presented again at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Her health had deteriorated significantly and she was in severe pain, so the doctors decided to treat her as an inpatient. She died on October 4, 1951 at the age of 31 of acute kidney failure with uremia . Lack's body was autopsied after her death, and doctors found that the cancer had already metastasized throughout the body .

Establishment of HeLa cells

A tissue sample taken from Henrietta Lacks tumor was given to the scientist George Otto Gey. The cancer researcher Gey worked together with his wife Margaret at the Johns Hopkins Hospital for almost 30 years on establishing a potentially immortal human cell line in order to be able to study findings on the growth behavior of degenerate cells. Up to this point in time, scientists had succeeded in generating permanent cell lines from animal cells, but all human cells cultivated up to that point in time stopped growing after a maximum of 30 to 50 divisions and died.

Gey isolated individual cells from the tumor tissue and brought them into culture. Among them was a cell whose growth and division behavior was different from that of the other cells. It divided at a particularly high rate and did not die even after a large number of cell divisions. Gey recognized that this cell line was potentially immortal, multiplied it and established a human cell line, which he named after the initials of the donor Henrietta Lacks HeLa for anonymization . The cell line name was later erroneously traced back to the names Henrietta Lakes , Helen Lane and Helen Larson .

The immunologist Jonas Salk had 1952 the first vaccine against the beginning of polio developed (poliomyelitis). Gey and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins Hospital found that the HeLa cells could be infected with the poliovirus and were much more sensitive to infection with the poliovirus than the primate cells previously used for vaccine testing. Since HeLa cells were needed on a large scale for testing polio vaccines from this discovery on, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis established a department for the mass production of HeLa cells at the Tuskegee Institute in 1952 . The institute did not have any commercial interests and made the cells available to laboratories and scientists. George Otto Gey also spread the cells through generous distribution among scientists.

Microbiological Associates later became the first company to produce and market HeLa cells commercially.

Research with HeLa cells

Approx. 11,000 registered patents worldwide are based on scientific findings from experiments with HeLa cells. More than 75,000 scientific articles based on experiments with HeLa cells are registered in the PubMed medical and scientific database . It is estimated that scientists have so far grown around 50 tons of HeLa cells. (Status: 2010)

In addition to testing the polio vaccine, HeLa cells were soon used for numerous different cell culture experiments in scientific research. The need for HeLa cells increased rapidly. After being mass-produced, they were shipped all over the world. In 1955, HeLa cells were the first human cells to be successfully cloned. They have been used for research into cancer, AIDS, the effects of radioactive radiation and toxic substances, for gene mapping and other scientific research purposes. HeLa cells are used to test human sensitivity to patches, glue, cosmetics, and many other products. The function of the polymerase enzymes was also determined using HeLa cells.

So far, four Nobel Prizes have been awarded for research using HeLa cells:

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2004 to Richard Axel and Linda B. Buck "for research into olfactory receptors and the organization of the olfactory system"

- Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine 2008 to Harald zur Hausen "for his discovery of the triggering of cervical cancer by human papilloma viruses"

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2009 to Elizabeth Blackburn , Carol W. Greider and Jack Szostak "for discovering how chromosomes are protected by telomeres and the enzyme telomerase "

- Nobel Prize for Chemistry 2014 to Eric Betzig , Stefan Hell and William Moerner "for the development of super-resolution fluorescence microscopy" ( Photoactivated Localization Microscopy , STED microscope )

Contamination of cell cultures by HeLa cells

In 1966, the scientist Stanley Michael Gartler determined that HeLa cells had apparently contaminated numerous cell culture approaches worldwide. Due to the high rate of division and the resulting high rate of reproduction, a single HeLa cell that is introduced into an existing cell culture as an impurity can overgrow the existing culture. In the 1960s, scientists had only very limited options for detecting the contamination of a cell culture with cells of the same species, as genetic analysis methods were not yet available. Gartler had determined a specific enzyme pattern of the respective cell lines by means of electrophoresis and was able to prove that this was identical in many of the cell lines he was investigating and at the same time could be clearly assigned to that of a black donor, although many of the cell lines investigated supposedly came from white donors.

In retrospect, Gartler's finding was often referred to as the HeLa bomb, as it called into question much of the scientific knowledge acquired on cell culture lines over the course of a decade and a half, because it could no longer be determined afterwards whether experiments were actually carried out on human cells or specific organs but were performed on the cancer cell-derived HeLa cells.

Legal and ethical controversy

Neither Henrietta Lacks nor her family had given her doctor permission to take the cells. At the time of the cell collection, the patient's consent was neither mandatory nor was it customary to obtain it. For several decades, the relatives and descendants of Henrietta Lacks did not know that the HeLa cells had been cultivated from the removed tumor cells and that these were used scientifically and commercially marketed worldwide. Johns Hopkins Hospital was one of the few hospitals in the area to treat African-American patients in the 1950s. Medical care was provided free of charge, but with tacit consent to participate in scientific studies.

After the contamination of numerous cell culture lines by HeLa cells became known, scientists contacted David Lacks, Henrietta's widower, to take blood samples from him and other relatives. They hoped to be able to create a genetic map of the HeLa cells by analyzing the DNA of the relatives in order to find markers with which HeLa cells could be clearly identified. Only then did the relatives find out that Henrietta Lacks cells were alive and used in laboratories around the world for experiments. When asked for an explanation, the family was presented with a textbook on cell biology, stating that the explanation was in this book. Since no family member had any basic medical knowledge, the family could not obtain any information from the book. The family only got more information about the cells from reporter Michael Gold, who contacted the family while researching an article about HeLa cells for Rolling Stone magazine.

During their research, the family learned that the HeLa cells were marketed around the world and had annual sales of several million US dollars, while Henrietta Lacks' descendants continued to live in poverty and in some cases could not even afford health insurance contributions could.

In the 1980s and 1990s, excerpts from the patient files of Henrietta Lacks and members of the family were published without their consent. A similar case was heard before the Supreme Court of California: in the Moore v. University of California case, the court ruled on July 9, 1990 that the tissue or cells removed from a person were not their property and could therefore be used commercially.

In 2013 the genome of a strain of HeLa cells was completely sequenced by scientists from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory . In accordance with the usual procedure, the entire genome sequence was published in the freely accessible databases of the European Bioinformatics Institute and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in order to make it available to other scientists for their research work.

The publication sparked a worldwide debate among scientists and bioethicists, as the published DNA sequence allows conclusions to be drawn about the genetic information of living and publicly known descendants of Henrietta Lacks. Although the scientists had not violated the applicable legislation, this approach was heavily criticized internationally.

Lars Steinmetz, the head of the research group that sequenced the genome, had the DNA sequence published on the Internet deleted and, through Rebecca Skloot, the author of a book about Henrietta Lacks, contacted the Lacks family to apologize. He offered the family a collaboration to find a way to publish the scientifically significant information while respecting the privacy of the Lacks family.

Finally, on August 7, 2013, an agreement was signed between the Lacks family and the National Institutes of Health , which guaranteed the family some control rights over access to the DNA code of the cells and the mention of Henrietta Lacks in scientific publications. In addition, two family members received seats on the six-member committee that decides on scientists' access to the DNA code.

After the identity of the donor of the HeLa cell line became known, Henrietta Lacks received numerous honors decades after her death. The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore has organized the Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture every year since 2010 , with which Henrietta Lacks and the significant contribution of HeLa cells to biomedical research are to be honored. The hospital also annually awards the US $ 40,000 Henrietta Lacks East Baltimore Health Sciences Scholarship to a Paul Laurence Dunbar High School student and the US $ 15,000 Henrietta Lacks Community Academic Partnership Award . In 2014, Henrietta Lacks received a spot in the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame. The tribute emphasized that Henrietta Lacks' story shows the importance of ethical action in modern science.

In 2011 the family of Henrietta Lacks Lacks founded the HeLa Foundation , a foundation to provide financial support to needy patients with cancer.

Plaques commemorate Henrietta Lacks at her former home in Clover ( Virginia ) and at the former home of the Lacks family in Maryland .

literature

- Rebecca Skloot: The Immortality of Henrietta Lacks. Irisiana-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-424-15075-9

- Friederike Lorenz: A bit of immortality - about the cells of Henrietta Lacks. In: Die Zeit No. 52, 2006, from December 20, 2006

- Katrin Blawat: An Eternal Life. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung from April 19, 2010

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rebecca Skloot: The Immortality of Henrietta Lacks. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 2013, p. 35, ISBN 978-3-442-15750-1

- ↑ Even dead, she still saves lives in 20 minutes from February 8, 2016

- ↑ D. Keiger: Immortal Cells, Enduring Issues. In: Johns Hopkins Magazine, June 2, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014

- ^ BP Lucey: Henrietta Lacks, HeLa Cells, and Cell Culture Contamination. In: Arch Pathol Lab Med. Vol. 133, September 2009, pp. 1463-1467

- ↑ Entry on HeLa cells on the homepage of the DSMZ - German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH

- ↑ D. Keiger: Immortal Cells, Enduring Issues. In: Johns Hopkins Magazine, June 2, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014

- ↑ D. Keiger: Immortal Cells, Enduring Issues. In: Johns Hopkins Magazine, June 2, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014

- ↑ R. Skoolt: An obsession on Culture. ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Pitt magazine. March 2001, accessed December 27, 2014

- ↑ RW Brown, JH Henderson: The mass production and distribution of HeLa cells at Tuskegee Institute, 1953–1955. In: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 38 (4), 1983, pp. 415-431.

- ↑ R. Skoolt: An obsession on Culture. ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Pitt magazine. March 2001, accessed December 27, 2014

- ↑ E. Brown: Monroe M. 'Monty' Vincent, early leader in cell-production industry, dies at 98. In: Washington Post March 7, 2011, accessed December 28, 2014

- ^ E. Callaway: Deal done over HeLa cell line - Family of Henrietta Lacks agrees to release of genomic data . In: Nature, Vol. 500, August 8, 2013, pp. 132-133

- ↑ Lisa Margonelli: Eternal Life. In: The New York Times. February 5, 2010, accessed June 27, 2015

- ↑ SM Gartler: Apparent HeLa cell contamination of human heteroploid cell lines. In: Nature. February 24, 1968 (5130), pp. 750-751. PMID 5641128

- ^ A. del Carpio: The good, the bad, and the HeLa - Perspectives on the world's oldest cell line. In: Berkley Science Review. April 27, 2014, accessed December 28, 2014

- ↑ HT Greely, MK Cho: The Henrietta Lacks legacy grows. In: EMBO reports, No. 10, Volume 14, 2013 p. 849; doi : 10.1038 / embor.2013.148

- ^ JL Stump: Henrietta Lacks and The HeLa Cell: Rights of Patients and Responsibilities of Medical Researchers. In: The History Teacher. Vol. 48 (1) 2014, pp. 127-180

- ^ E. Callaway: Deal done over HeLa cell line - Family of Henrietta Lacks agrees to release of genomic data. In: Nature, Vol. 500, August 8, 2013, pp. 132-133

- ^ S. Zielinski: Henrietta Lacks `` Immortal 'Cells. Smithsonian.com, January 22, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2014

- ^ E. Callaway: Deal done over HeLa cell line - Family of Henrietta Lacks agrees to release of genomic data. In: Nature, Vol. 500, August 8, 2013, pp. 132-133

- ^ RE Kisner, EF Granton: Family Talks About Dead Mother Whose Cells Fight Cancer. In: Jet Magazine, April 1, 1976, pp. 16-18, 53

- ↑ HW Jones: Record of the first physician to see Henrietta Lacks at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: history of the beginning of the HeLa cell line. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. (176) 1997, pp. 227-228.

- ↑ J. Landry et al .: The Genomic and Transcriptomic Landscape of a HeLa Cell Line. In: 3G Genes Genomes Genetics. Volume 3, August 2013, pp. 1213-1224; doi : 10.1534 / g3.113.005777

- ↑ HT Greely, MK Cho: The Henrietta Lacks legacy grows. In: EMBO reports, No. 10, Volume 14, 2013 p. 849; doi : 10.1038 / embor.2013.148

- ↑ R. Skloot: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the Sequel. In: The New York Times, March 23, 2013, accessed December 30, 2014

- ↑ HT Greely, MK Cho: The Henrietta Lacks legacy grows. In: EMBO reports, No. 10, Volume 14, 2013 p. 849; doi : 10.1038 / embor.2013.148

- ^ KL Hudson, FS Collins: Biospecimen policy: Family matters. Nature 500, Aug 8, 2013, pp. 141-142; doi : 10.1038 / 500141a

- ^ M. Adams: First Annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture at Johns Hopkins. published on the Johns Hopkins Hospital homepage on October 3, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014

- ^ M. Adams: First Annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture at Johns Hopkins. published on the Johns Hopkins Hospital homepage on October 3, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014

- ^ Entry by Henrietta Lacks on the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame home page, accessed June 27, 2015

- ^ J. Franzos: An immortal legacy - Hopkins and the community reflect on contributions of Henrietta Lacks at the second annual lecture. In: Inside Hopkins. News bulletin for employees throughout Johns Hopkins Medicine. October 13, 2011

- ^ M. Stefano, N. King: Days of our lives. March 26, 2014, accessed December 27, 2014