Henrietta Lacks

Henrietta Lacks (born August 1, 1920 in Roanoke, Virginia ; † October 4, 1951 in Baltimore , Maryland), also incorrectly named Henrietta Lakes , Helen Lane or Helen Larson , was an American woman who took a tissue sample from a Cervical carcinoma from which the first immortal human cell line was cultured without her knowledge. The cells, which were named HeLa cells after Henrietta Lack's initials , are still used in medical research today.

Life

Childhood and family

Henrietta Lacks was born on August 1, 1920 as the ninth child of Eliza (née Lacks) (July 12, 1888 - October 28, 1924) and John Randall Pleasant (1881–1969) as Loretta Pleasant in Roanoke (Virginia). It is uncertain when and why her first name was changed from Loretta to Henrietta. The father was a train brake , the family lived in poor conditions. Her mother died giving birth to her tenth child in October 1924 when Henrietta was four years old. Henrietta's father, unable to cope with caring for the children, moved with them to Clover, Virginia , where his family ran a tobacco plantation, and placed the children with various relatives. Henrietta was given to her grandparents Chloe and Tommy Lacks, who lived in a simple wooden hut that had previously served as slave accommodation.

The ancestors of Henrietta's father's family had worked as slaves on the tobacco plantation of the white Lacks family. Henrietta's white great-grandfather, Albert Lacks, had several children with one of his female slaves. By the time Albert Lacks died in 1889, slavery had already been abolished and he bequeathed five black heirs, including Henrietta's grandfather Tommy Lacks, a piece of land each. Although Albert Lacks had not officially recognized the heirs as his children, it was common knowledge in the village that these were his descendants, which is why the heirs also took the surname Lacks. The lands of the black Lacks family were called Lackstown in the area .

When Henrietta came to her grandparents, they were already looking after Henrietta's cousin David "Day" Lacks (* 1915; † 2002), the illegitimate son of one of her daughters, who was five years her senior. Henrietta and David, who shared a room, had to work hard on the farm and around the house. Since he had to help the family with the field work, David left school after the fourth grade; Henrietta attended school for six years.

In 1935, 14-year-old Henrietta Pleasant gave birth to their first son, Lawrence, whose father was her cousin David. In 1939, their second child, Lucille Elsie († 1955), was born. David Lacks and Henrietta Pleasant married two years later on April 10, 1941 in Halifax County, Virginia. Shortly after the marriage, David Lacks first moved to Maryland alone to work at the Sparrow Point shipyard. His cousin Fred Garrett, who had left the plantation a year earlier, had persuaded him to do so because he believed that the city had better living conditions and income opportunities.

After David Lacks had earned enough money, he bought a house in Turner Station , a settlement that was almost exclusively black workers and which is now part of Dundalk, Maryland . Henrietta then also left the tobacco plantation and moved with the children to her husband. In the following years the couple had three more children: David Jr. (* 1947), Deborah (* 1949; † 2009) and Joseph (* 1950), who later changed his name to Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman.

In 1951, daughter Elsie was taken to the Hospital for the Negro Insane of Maryland , a mental health clinic, because her parents noticed she was mentally retarded. She was later diagnosed with epilepsy. Elsie died there in 1955 at the age of 15.

Cancer and death

Henrietta Lacks was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital on January 29, 1951 because she suffered from profuse irregular abdominal bleeding in November 1950 after giving birth to her fifth child, Joseph. Her family doctor initially suspected a syphilis infection . The diagnostic test he initiated turned out negative, which is why he referred her to the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for further examination. Johns Hopkins Hospital was the only hospital in the wider area that treated African Americans in the 1950s.

At Johns Hopkins Hospital, she was examined by gynecologist Howard W. Jones , who found a 2 to 3 cm lump on her cervix . This was unusual in that Henrietta Lacks had given birth to her youngest son only 4½ months earlier and no changes to the cervix were noticed either during the gynecological examinations during the birth or during the examination 6 weeks after the birth.

Jones took tissue samples from the tumor, which he had pathohistologically examined. Here one was squamous cervical diagnosed, where the tumor was later subsequently identified as an adenocarcinoma.

Doctors treated Henrietta Lacks with internal radiation therapy by applying a sheathed radium implant to her that remained in her body for a few days. After the implant was removed, Henrietta Lacks was initially discharged from the hospital with instructions to undergo supplementary external radiation therapy with X-rays after a few days, which would be carried out on an outpatient basis at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. During one of these radiation sessions, two more tissue samples were taken from her cervix: one from the healthy cervical tissue and one from the tumorous area. These samples were given to George Otto Gey , who at the time was working at Johns Hopkins Hospital to create a potentially immortal cell line. From these cells the potentially immortal HeLa cell line emerged.

On August 8, 1951, Henrietta Lacks presented for another radiation session at Johns Hopkins Hospital. She was in severe pain and her health deteriorated, so the doctors decided to treat her as an inpatient. She developed acute kidney failure with uremia , from which, despite treatment and a blood transfusion, she died on October 4, 1951, at the age of 31, just eight months after the cancer was diagnosed.

Henrietta Lacks' body was autopsied, and the doctors found that the cancer had already metastasized throughout the body.

Henrietta Lacks was buried in a family funeral on her family's plantation in Clover. The exact location of the grave is unknown today as no tombstone was erected.

Establishment of HeLa cells

Howard W. Jones gave a tissue sample taken from Henrietta Lacks' tumor to his colleague, cancer researcher George Otto Gey, who had been working with his wife Margaret at Johns Hopkins Hospital for almost 30 years to establish a potentially immortal human cell line. Up to this point in time, natural scientists had established permanent cell lines from animal tissue, but all human cell lines cultivated to date stopped dividing after a maximum of 30 to 50 divisions and died.

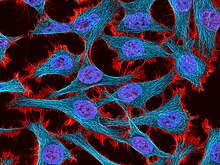

Gey succeeded in isolating a cell line from Henrietta Lacks' tumor tissue that divided at a particularly high rate and did not die even after a large number of divisions. He realized that this cell line was potentially immortal and propagated it. To make it anonymous, he named the new cell line after the initials of the donor Henrietta Lacks HeLa .

Gey and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins Hospital recognized that the HeLa cells very well for testing 1952 after immunologists Jonas Salk developed vaccine against polio suitable (poliomyelitis). From then on, HeLa cells were required on a large scale for vaccine production, which is why the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis established a department for the mass production of HeLa cells at the Tuskegee Institute in 1952 . This institute made the HeLa cells available to laboratories and scientists, but did not pursue any commercial interests. George Otto Gey also generously passed the cells on to other scientists.

Microbiological Associates later became the first company to produce and market HeLa cells commercially.

The HeLa cells are relatively easy to cultivate under laboratory conditions and were soon used for researching a wide range of scientific issues. With their help, important contributions have been made to research into cancer, AIDS, the effects of radiation and toxic substances, and gene mapping. HeLa cells have been used to test human sensitivity to patches, adhesives, cosmetics, and many other products. It is estimated that around 50 tons of HeLa cells have been grown so far. Almost 11,000 patents covering HeLa cells are registered worldwide.

Appreciation

- On June 4, 1997, Congressman Robert L. Ehrlich paid tribute to Henrietta Lacks in a speech to the United States House of Representatives for the great contribution that HeLa cells have made to modern medicine, while they themselves had been almost forgotten.

- The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore has hosted the Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture annually since 2010 . This lecture event is intended to honor Henrietta Lacks and the globally significant contribution of HeLa cells to biomedical research. The hospital also sponsors the $ 40,000 annual Henrietta Lacks East Baltimore Health Sciences Scholarship for a Paul Laurence Dunbar High School student and the $ 15,000 Henrietta Lacks Community Academic Partnership Award.

- In 2011, the family of Henrietta Lacks set up the Lacks Family HeLa Foundation , a foundation that provides financial support to needy patients suffering from cancer.

- In Clover, Virginia, the place where Henrietta Lacks grew up after her mother died, a plaque commemorates Henrietta Lacks.

- In 1996 the Atlanta Morehouse School of Medicine, the State of Georgia and the Atlanta Mayor recognized descendants of Henrietta Lacks' family for their posthumous contributions to medical research.

- After reading the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks , Dr. Roland Pattillo of the Morehouse School of Medicine placed a tombstone for Henrietta Lacks grave in 2010. The inscription on the tombstone, which is designed in the shape of a bush, reads:

"Henrietta Lacks, August 01, 1920-October 04, 1951. In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many. Here read Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever. Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family "

“Henrietta Lacks, August 1, 1920 - October 4, 1951. In fond memories of an outstanding woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many. Henrietta Lacks (HeLa) rests here. Your immortal cells will serve humanity forever. Eternal love and admiration, from your family "

- In the Turner district, a plaque commemorates Henrietta Lacks on the former home of the Lacks family. This was attached by the Henrietta Lacks Legacy Group, which wants to preserve their memory. A few years later her life was commemorated annually in a ceremony by the residents of Turner's station. Robert Ehrlich passed a resolution in her honor. Memorial services were also held in the Turner Station's community to honor other people involved in the discovery and establishment of HeLa cells, including Mary Kubicek, the laboratory assistant who discovered that HeLa cells were viable outside the body, and George Otto Gey and his wife Margaret Gey, who after more than twenty years of collaborative research finally succeeded in cultivating human cells outside the body.

- In 2011, Morgan State University awarded Henrietta Lacks a posthumous honorary degree.

- On September 14, 2011, the board of directors of the Washington ESD 114 Evergreen School District in Vancouver, Washington, decided to name a new high school for medicine and life sciences after Henrietta Lacks. The school opened in autumn 2013 is called Henrietta Lacks Health and Bioscience High School .

- Henrietta Lacks received a spot in the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame in 2014. The award highlighted the fact that the story of Henrietta Lacks made scientists aware of the importance of ethical behavior in modern science.

reception

In the media

In response to HeLa cell contamination of cell cultures, Michael Gold published the book A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy and the Medical Scandal It Caused in 1986 . He only goes into the margins of Henrietta Lacks and mainly deals with the scientific work of Walter Nelson-Rees on the elucidation of the contamination of cell cultures by HeLa cells.

In 1997 Adam Curtis directed the one-hour documentary The Way of all Flesh about Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa cell for the BBC . The following year the film won the award for best science documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival .

Immediately after the film aired in 1997, journalist Jacques Kelly published an article about the HeLa cells, Henrietta Lacks and her family in the Baltimore Sun. In the 1990s, the Dundalk Eagle published the first article about her in a Baltimore City and Baltimore County newspaper and continues to report on local memorial events. In 2001 the National Foundation for Cancer Research announced that it would honor the late Henrietta Lacks on September 14, 2001 for her contribution to cancer research and modern medicine. However, the event was canceled due to the events on September 11, 2001 .

In articles in 2000 and 2001 and in her book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks , published in 2010, author and journalist Rebecca Skloot documented both the history of the Lacks family and HeLa cells. In May 2010, HBO announced that Oprah Winfrey and Alan Ball were planning a film project based on Rebecca Skloot's book. In 2017 the film The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks with Renée Elise Goldsberry in the title role, Oprah Winfrey as Deborah Lacks, Rocky Carroll as Sonny Lacks and Rose Byrne as Rebecca Skloot was released.

In June 2013, Henrietta Lacks eldest son Lawrence Lacks and his wife Bobbette posted a short digital reminder entitled Hela Family Stories: Lawrence and Bobbette on the Lacks family homepage. Lawrence Lacks describes his memories of his mother and his wife Bobbette reports on the struggle to protect Henrietta Lacks' orphaned children from an abusive situation.

In art

In 2010, NBC aired an episode called Immortal in its 20th season of the series Law & Order , in which a tissue sample is taken from a patient and a company makes a big profit with its cells. The fictional story is heavily based on the story of Henrietta Lacks. In the action film Project Power , which was released on Netflix in 2020 , Lacks is also mentioned when a former soldier is looking for his daughter who was kidnapped because of her special body cells.

Various bands were inspired to create songs by the story of Henrietta Lacks. The band Mal Webb released the song Helen Lane on their album Mal Webb 1, which was released in 2000 . The lyrics go into the great contribution of HeLa cells to medical research, but also to the ethical question of the use of the cells without the knowledge and consent of the patient.

The 2011 album Enhanced Methods of Questioning by the American band Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine contains the song The Cells That Will Not Die about Henrietta Lacks and the immortal HeLa cells. In 2012 the band Yeasayer also released the single Henrietta , the first release from their third album Fragrant World , a song inspired by Henrietta Lacks' story.

Adura Onashile wrote the one-person play HeLa , based on the story of Henrietta Lacks , which was performed at the Edinburgh Festival 2013 and the National Arts Festival 2014, among others .

The play HeLa by American writers Lauren Gunderson and Geetha Reddy premiered on May 22, 2017 at the Live Oak Theater in Berkeley , California.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rebecca Skloot: The Immortality of Henrietta Lacks. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-442-15750-1 , p. 35.

- ^ DM Watson: Cancer cells killed Henrietta Lacks - then made her immortal. In: The Virginian Pilot. May 10, 2010, pp. 1, 12-14, accessed December 26, 2010.

- ↑ Rebecca Skloot: The Immortality of Henrietta Lacks. Goldmann Verlag, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-442-15750-1 , p. 176.

- ↑ J. Kelly: Her cells made her immortal - Research: A Turners Station woman donated cells that revolutionized medical science In: The Baltimore Sun, March 18, 1997, accessed January 1, 2015.

- ↑ a b c D. Keiger: Immortal Cells, Enduring Issues. In: Johns Hopkins Magazine. dated June 2, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014.

- ^ BP Lucey: Henrietta Lacks, HeLa Cells, and Cell Culture Contamination. In: Arch Pathol Lab Med. Vol. 133, September 2009, pp. 1463-1467.

- ↑ Entry on HeLa cells on the homepage of the DSMZ - German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH .

- ↑ R. Skoolt: An obsession on Culture. ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Pitt magazine. March 2001, accessed December 27, 2014.

- ↑ RW Brown, JH Henderson: The mass production and distribution of HeLa cells at Tuskegee Institute, 1953–1955. In: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 38 (4), 1983, pp. 415-431.

- ↑ R. Skoolt: An obsession on Culture. ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Pitt Magazine March 2001, accessed December 27, 2014.

- ^ E. Brown: Monroe M. 'Monty' Vincent, early leader in cell-production industry, dies at 98. In: Washington Post, March 7, 2011, retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ Lisa Margonelli: Eternal Life. In: The New York Times, February 5, 2010, accessed June 27, 2015.

- ↑ RL Ehrlich: In Memory of Henrietta Lacks. June 4, 1997. In: Congressional Record. Volume 143, Number 75, p. E1109.

- ^ A b M. Adams: First Annual Henrietta Lacks Memorial Lecture at Johns Hopkins. published on the Johns Hopkins Hospital homepage on October 3, 2010, accessed December 25, 2014.

- ^ J. Franzos: An immortal legacy - Hopkins and the community reflect on contributions of Henrietta Lacks at the second annual lecture. In: Inside Hopkins. News bulletin for employees throughout Johns Hopkins Medicine. October 13, 2011.

- ^ DM Watson: After 60 years of anonymity, Henrietta Lacks has a headstone. In: The Virginian Pilot. May 30, 2010, accessed December 26.

- ^ M. Stefano, N. King: Days of our lives. Dated March 26, 2014, accessed December 27, 2014.

- ^ Henrietta Lacks. In: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: Paving a Path of Excellence for Maryland's Future. Maryland Women's Hall of Fame - 2014 Induction Ceremony. P. 14.

- ↑ M. Gold: A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy and the Medical Scandal It Caused. State University of New York Press. 1986, ISBN 978-0-88706-099-1 .

- ^ Video of the film The Way of all Flesh on the BBC homepage, accessed on December 26, 2014.

- ^ Private homepage of the Lacks family in memory of Henrietta Lacks, accessed on June 27, 2015.

- ↑ Summary of the episode Immortal on the All Things Law & Order homepage , accessed on January 1, 2014.

- ^ All Things Law And Order: Law & Order “Immortal” Recap & Review. In: allthingslawandorder.blogspot.de. May 18, 2010, accessed July 14, 2015 .

- ^ Text of the song Helen Lane on the homepage of the band Mal Webb. accessed on January 1, 2015.

- ↑ NME News Yeasayer reveal new track 'Henrietta'. In: nme.com. May 16, 2012, accessed July 14, 2015 .

- ^ HeLa - Theater Performance, University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand. (No longer available online.) In: otago.ac.nz. October 16, 2014, archived from the original on July 1, 2015 ; accessed on July 14, 2015 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ http://www.sfgate.com/performance/article/TheatreFirst-s-HeLa-reclaims-cells-as-11167864.php

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lacks, Henrietta |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lane, Hellen; Lakes, Henrietta; Larson, Helen |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American cancer patient and cell donor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 1, 1920 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Roanoke (Virginia) |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th October 1951 |

| Place of death | Baltimore ( Maryland ) |