Leipzig trade bourgeoisie

The Leipzig trade bourgeoisie describes a historical social sub-grouping of the bourgeoisie , which emerged from the urban patriciate from the Middle Ages and existed as an outstanding social class from around the middle of the 16th century until its dissolution in 1945. The rise owed the commercial bourgeoisie of the location of the city at the intersection of two important trade routes - Via Regia and Via Imperii - for the long-distance trade and the imperial fair privilege of 1497, the City of Empire Fair rose. The dissolution of the urban social class took place through overarching transformation processes with the aim of establishing a socialist society in the GDR .

groups

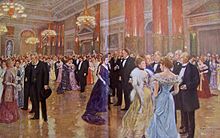

The Leipzig trade bourgeoisie represented the largest group of the entire Leipzig upper class. These were merchants, manufacturers , bankers , publishers , and in a broader sense also large landowners . There was also the elite of academic teaching staff, mainly professors who belonged to the middle class upper class. Both groups were closely related to the city council members and the richest Leipzig families. The civil servants of the sovereign administration, doctors, pastors, officers and schoolmasters also belonged to the educated class of the entire upper class . Mixing of the items took place.

The layer exhibited a high level of cohesion as well as strong family links. As the leading representatives of their social class in the Electorate of Saxony and the subsequent Kingdom of Saxony , they shaped and shaped almost all social and political fields of their time to a large extent . As representatives of commercial capitalism and thus lobbyists of important Leipzig financial institutions such as the Leipziger Bank , commercial institutions such as the Old Stock Exchange and later the New Stock Exchange, as well as industrial companies, they guided social and economic flows in the Saxon state to a large extent, factually and informally. Thanks to her excellent international network, everything she did had an impact abroad. They also used their family networks across industries.

Commerce, culture and art

The exemplary forms of action included investments, speculations, purchases, sales, aid, donations, patronage and other forms of social exchange that were typical for representatives of the upper class of Europe.

Civil institutions also included the press and books. The shaping of public opinion was also part of the sphere of influence of the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie. This also includes the Leipzig Book Fair and the Leipzig Book Trade . The Leipzig trade fair remained the most important platform until the socialist upheaval after 1945 .

The Leipzig trade bourgeoisie was active in promoting art and culture, but above all with an emphasis on music. This led to the establishment of internationally important high culture institutions, which in turn entailed engagements by well-known music stars of their time. This included, for example, Johann Sebastian Bach , Philipp Telemann , Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy , Robert Schumann , Albert Lortzing , Gustav Mahler , who worked at least temporarily in the prosperous trade fair city. The patrons wanted to raise the reputation of their city. This form of financial generosity for the Leipzig community was taken for granted in the upper circles.

history

Far away from the Saxon court and royal tutelage, endowed with trade fair privileges , located at an internationally important intersection of Via Regia and Via Imperii, the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie grew up and benefited from this favorable initial situation.

In the 16th century, Leipzig's trading capital had made a decisive contribution to the development of the productive forces in Saxony, especially in the field of textile production. The Leipzig merchants also made their profit by acquiring Kuxen and shares in Berggeschrey in the Ore Mountains .

The influences and influences on Saxony began in the Middle Ages and continued until the end of Leipzig's social class. Nikolaus Krell , Chancellor at the end of the 16th century, tried to carry out a Calvinist revolution in Saxony but failed. His power base was limited to the trust of the Elector, a small group of Reformed preachers and a minority of intellectuals who - like the Chancellor himself - mostly came from the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie.

Saxony's most important ruler , August the Strong, found an important economic foundation for his ambitious political goals in the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie. This created reliable partnerships through lending in Eastern Europe.

The Leipzig trading exchange was established in 1678 . In 1699, Leipzig and Saxony's first bank, the Banco di Depositi, was founded .

The main lines of political interests were always the same. Trade should not be hindered by customs barriers or monopolies . The wholesale merchants should have a completely free hand in shaping their foreign trade . Trade contracts were supposed to secure the free development of Saxon trade and enable the sale of Saxon products.

The Saxon upper bourgeoisie, which was hampered in its economic development in the second quarter of the 18th century by the financial mismanagement in the Brühl era , was unable to exert any significant political influence at that time. However, the crisis in Saxony after the Seven Years' War meant that bourgeois forces from the circles of the Saxon wholesalers and manufacturing entrepreneurs were also involved in shaping the future politics and economic management of Saxony. The Restoration Commission, headed by the Secret Council Thomas von Fritsch , who emerged from the Leipzig merchant bourgeoisie , was given the task of drawing up reform plans.

The foundation of the Leipziger Ökonomische Sozietät falls in the years of the Electoral Saxon retablissement . The initiator of this society was Peter von Hohenthal , who came from the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie .

The Leipzig trade bourgeoisie, whose trade depended on the favor of the elector, was hostile to the French Revolution .

Among others, Carl Lampe , Gustav Harkort , Gustav Moritz Clauss , Adolf Heinrich Schletter and Heinrich Brockhaus belonged to the Leipzig trading bourgeoisie. Most of them were involved in one way or another in the beginning industrial revolution of the 1830s.

The citizens of Leipzig invested primarily in the infrastructure sector. With the construction of a railway connection to the Elbe, the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie had put their Magdeburg counterparties under pressure, who in turn now developed a vital interest in a train connection to Leipzig. During the preparation and construction of the Leipzig – Hof railway line , there was much closer cooperation between the state and the Leipzig trade bourgeoisie.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Ufer: Leipziger Presse 1789 to 1815: a study on development tendencies and communication conditions in the newspaper and magazine industry between the French Revolution and the Wars of Liberation, LIT Verlag Münster, 2000, pp. 74f

- ↑ Michael Schäfer: Family businesses and entrepreneur families: on the social and economic history of Saxon entrepreneurs, 1850-1940, Volume 18 of series of publications on the journal for corporate history, CH Beck, 2007, p. 68

- ↑ Die Alte Stadt, Volume 26, W. Kohlhammer, 1999, p. 98

- ^ Trade relations between Saxony and Italy 1740–1874: a source publication, H. Böhlaus, 1974, Volume 9 of the series of publications by the Dresden State Archives, Dresden State Archives, p. 18

- ↑ Frank Müller: Kursachsen and the Bohemian Uprising 1618–1622, Volume 23 of the series of publications of the Association for Research in Modern History, Association for Research in Modern History, Aschendorff, 1997, p. 48

- ↑ Wolfgang Stellmacher: Places of German Literature: Studies on literary centers formation 1750-1815, Lang, 1998, p. 76

- ^ Trade relations between Saxony and Italy 1740–1874: a source publication, H. Böhlaus, 1974, Volume 9 of the series of publications of the Dresden State Archives, Dresden State Archives, p. 50

- ↑ Gerd-Helge Vogel, Hermann A. Vogel von Vogelstein, Christian Leberecht Vogel : Christian Leberecht Vogel, Gutenberg, 2006, p. 5

- ↑ Yearbook for the History of Feudalism, Volume 2, Akademie-Verlag, 1978, p. 359

- ^ Yearbook of the Institute for German History, Volume 8, Institute for German History, 1979, p. 48

- ↑ Die Alte Stadt, Volume 26, W. Kohlhammer, 1999, p. 87

- ^ Rainer Karlsch, Michael Schäfer: Economic history of Saxony in the industrial age, Edition Leipzig, 2006, p. 40

- ^ Rolf Bayer, Gerd Sobek: The Bavarian train station in Leipzig: Origin, development and future of the oldest terminal station in the world, Transpress VEB Verlag für Verkehrwesen, 1985, p. 12