Levi Coffin

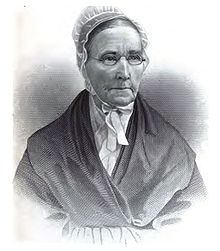

Levi Coffin (born October 28, 1798 near New Garden, Guilford County , North Carolina , † September 16, 1877 in Avondale , now a district of Cincinnati , Ohio ) was an American Quaker , abolitionist and businessman. He was heavily involved in the Underground Railroad in Indiana and Ohio. His house has often been referred to as the "Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad". He was nicknamed "President of the Underground Railroad" because of the escaped slaves, who numbered in the thousands, and because of the care he gave them when they flew from their masters.

Coffin immigrated from North Carolina to Indiana in 1826 after the Quakers were persecuted by slave owners. In Indiana, he ran a local business, was the branch manager of a Bank of Indiana branch in Richmond, and was a trader and farmer. His position in the community allowed him to provide sufficient funds to support the Underground Railroad operations in his area, which included food, clothing and transportation. At the urging of friends in the anti-slavery movement, he moved to Cincinnati in 1847 and ran a warehouse there that only sold goods that were produced by free workers. Despite considerable progress in his business, the company was unprofitable and in 1857 he was forced to sell it. When slavery was abolished after the American Civil War , Coffin traveled across the Midwestern United States and abroad to France and Great Britain , where he was instrumental in the formation of aid organizations that provided free slaves with food, clothing, and money and provided education.

Early years

Family and origin

Levi Coffin, son of Levi Coffin Sr., was born on October 28, 1798 in a factory near New Garden, Guilford County, North Carolina. He was the only son, but had six sisters. Coffin's grandfather immigrated with his parents to New England from Leicestershire , England around 1740 . Coffin's father was born in Massachusetts in the 1760s and immigrated to North Carolina from Nantucket , where he ran a farm in a Quaker community. The family was strongly influenced by the teachings of John Woolman , who believed that slavery was incompatible with the Quaker beliefs and therefore fought for the emancipation of slaves. Coffin's parents likely met with the non-slave Quaker families during one of the religious gatherings near their home in New Garden in 1767. Coffin's cousin, Vestal Coffin, was also likely to attend the meeting. Vestel was one of the early Quakers to help escaped slaves in North Carolina as early as 1819.

Coffin grew up on his father's farm where he received little, if any, formal education. Throughout his childhood he had frequent contact with slaves and therefore sympathized with them. Consistent with his own description, he became an abolitionist at the age of seven after asking a slave chained in a group why he was chained. The man replied that he was prevented from fleeing to return to his wife and children. This event disturbed the boy, who often considered the possibility that his own father might be stolen from him in a similar way. At the age of 15, he helped his family feed escaped slaves who were hidden on his farm. When the repressive Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was enforced more rigorously, the family was forced to conduct their activities regarding the slaves with greater secrecy, so they began performing most of their illegal activities at night. The situation has deteriorated progressively since the enactment of the Black Laws of 1804.

Moved to Indiana

From the early 1820s onwards, Quakers in North Carolina were persecuted for their underwriting of escaped slaves. In 1821, Coffin and his cousin opened a Sunday school teaching slaves to read the Bible. The venture was short-lived as slave owners forced both of them to close the school. Thousands of Quakers began moving to the Northwest Territory , where slavery was illegal and the land was cheap. There was already a large Quaker community there that was influential in enacting constitutional bans on slavery in Ohio and Indiana . In 1822, Coffin accompanied his brother-in-law Benjamin White on his move to Indiana. He stayed in Indiana for over a year with the Whites before returning to North Carolina. Coffin came back with reports on Indiana and its wealth. Convinced that the Quakers and slavery cannot coexist, he decided to move to Indiana himself.

On October 28, 1824, Coffin married his longtime girlfriend Catherine White, his brother-in-law's sister. The ceremony was held at the Hopewell Friends Meetinghouse in North Carolina. Catherine's family believed that she had helped escaped slaves and that was how they met while doing the job. The couple postponed their move to Indiana because Catherine became pregnant with Jesse, the first of six children, who was born in 1825. Coffin's parents moved to Indiana that year. They met in Newport in 1826, later renamed Fountain City , (Indiana).

Underground Railroad

Indiana

After moving to Indiana, Coffin began farming a strip of land that he bought soon after his arrival. Then, within a year, he also opened a general store. Years later, his experience in the business gave him the ability to do so successfully in the Underground Railroad, which was a costly endeavor financially. Consistent with his own report, he discovered not long after moving that his house was on a line of the Underground Railroad Stops. It stemmed from the fact that there was a large community of free blacks near Newport, where the fugitive slaves hide before heading north. Often they were captured again because their hiding place was well known. Coffin was in contact with the black community and made it clear to them that he was ready to hide the runaway slaves near his home to better protect them. Although the term " Underground Railroad " was not used until the 1830s, the organization had operated in Indiana since the early 1820s. Coffin was commonly referred to in the system as the "mysterious road".

The first time he brought a runaway slave to his new house was in the winter of 1826/1827. The news of his actions quickly spread through the community. Although many had previously been concerned about participating, they joined him after his success. The group formed a more formal route where the escaping slaves could move from one stop to another until they reached Canada . Over time, the number of runaway slaves increased. Coffin estimated that he helped an average of one hundred escaped annually. Coffin's house became the point of convergence of three major escape routes from Madison , New Albany, and Cincinnati. The fugitives gathered at his house and at times two wagons were needed to transport them north. Coffin transported them from one stop to the next during the night. His house saw so many fugitives pass that it became known as the "Grand Central Station of the Underground Railroad."

Coffin's life was often threatened by slavers, and many of his friends feared for his safety. They tried to dissuade him from his activities by warning him of the danger to his family and business. However, Coffin was deeply driven by his religious beliefs and wrote these fears down in his later life:

“After listing these advisors, I calmly told them that I feel no condemnation for anything that I had ever done for the fugitive slaves. If I do my duty and try to meet the Bible's injunctions, I will damage my business and then give it up. For my safety, my life was in the hands of my heavenly Lord and I felt that I had His approval. I was not afraid of the danger that seemed to threaten my life or my business. When I do my job diligently, sincerely and diligently, I feel that I would be protected and that I would have done enough to support my family. "

There was a time when his business made very little money. Neighbors who opposed his activity boycotted his business. However, Indiana’s population grew rapidly and the majority of the new immigrants supported anti-slavery, so Coffin's business began to grow. His prosperity expanded, so he made a sizable investment in the Bank of Indiana when it was built in 1833. He soon became the branch manager of a branch for the bank in Richmond, Indiana. In 1836 he built a mill and started producing linseed oil . Two years later, in 1838, Coffin built a new two story brick house and made some changes to his house to provide better hiding places for the slaves. A secret door was installed in the maids' quarters, where fourteen people could hide in the narrow false ceiling between the walls. The room was often used when slavers came to Coffin's house to look for escapes.

During the 1840s, pressure was put on the Quaker communities to help escaped slaves. In 1842, leaders of the Religious Society of Friends , the Quaker church group that heard from Coffin, advised all of their members to end membership in the abolitionist societies and thus cease activities related to the escaped slaves. They insisted that legal emancipation was the best course of action. In the following year, they denied Coffin and expelled him from their community because of his active role with the free slaves and his negative attitude towards the stop. Coffin and other Quakers who supported his activities separated and formed the Antislavery Friends . The two groups remained separate until reunification in 1851.

Despite the opposition, his activity increased and he wanted to do more to help the free blacks. Catherine organized a sewing club that met at Coffin's house to make clothes to be given to the runaway. Other support was the search for neighbors who were sympathetic but unwilling to take escapes into their homes. Through these activities he was able to guarantee a stable supply of goods for the operations. Over the years he came to realize that much of the goods he sold in his business were produced by slave labor. While traveling, he met organizations in Philadelphia and New York City that only sold goods produced by free workers. He began by buying inventory from the organizations and selling them to his abolitionist companions, making next to no profit from the sale of these products.

The advocates of free labor in the east wanted to create a similar organization in the west. The Salem Free Produce Association members asked Coffin if he would be interested in running the proposed Western Free Produce Association . He initially declined, saying he didn't have the money to fund the project and that he didn't want to move to town. Various groups put pressure on him to accept the position, for there was no one else who was more qualified among the Western abolitionists. He and his wife were happy with their country lives and didn't want to move to town. In the end he reluctantly accepted, but only agreed to oversee the camp for five years until the business went well and he could train some to run it.

Ohio

With the help of other businessmen, a depot was opened in Cincinnati, which served as a warehouse for goods in 1845. The Free Produce Association raised $ 3,000 to open the store. Coffin moved to the city in 1847, where he took over the management of the wholesale warehouse. He rented out his Newport business before leaving as he ultimately intended to return. With the help of the Eastern organizations he was in the warehouse to procure goods for the market. His persistent problem was being able to get goods that were made by free laborers and produced to the same quality as those of slave laborers. The problem plagued the business for years, so the company was constantly struggling to survive.

The problem caused Coffin when he began to travel south to find plantations there that did not use slaves. He had only limited success with it. He found a cotton plantation in Mississippi where the owner had released all of his slaves and paid them as free laborers. The plantation gnawed at starvation and all work was done manually. Coffin helped the owner by purchasing an Egrenier machine which greatly increased its production so that a steady supply of cotton was assured for his company. The cotton was shipped to Cincinnati, where it was spun into cloth and sold. Other trips to Tennessee and Virginia were less successful, although he was more successful in promoting the movement. Despite his constant diligence in business, problems with the availability of cheap and quality products from free workers proved insurmountable, so in 1857 Coffin had to sell the business.

Cincinnati already had a major anti-slavery movement in the city and a violent history of advocates for slavery. He bought a new house on the corner of Elm and Sixth Streets. He was also still active in the Underground Railroad, established a new safe shelter in the city and helped organize a large network in the area. In the beginning he was very careful in helping slaves until he was able to find people in the community whom he could trust and they him. Coffin moved around town a few times and eventually settled on Wehrman Street . It was a big house and the rooms were rented immediately upon entering. With the many guests coming and going, the house was an excellent place for an underground railroad stop without arousing much suspicion. Catherine created costumes for the fugitives who were then dressed up as butlers, cooks and other workers. Some of the mulattos were even able to pass as white guests. The most common disguise used was that of a Quaker woman. The long collar, long sleeves, gloves, veil and a large brimmed hat could completely hide the wearer as soon as he lowered his head slightly.

One of the many slaves Coffin helped escape was Eliza Harris. The girl had escaped from the south and crossed the Ohio River one winter night when it was frozen over. Barefoot and carrying her baby, she was exhausted and near death by the time she reached Coffin's house. He provided her with food, new shoes, and shelter before helping her travel to freedom in Canada. Harriet Beecher Stowe was living in town at the time and was well acquainted with the coffins. She was so moved by the story that it served her for her book Uncle Tom's Cabin . Levi and Catherine Coffin both believed they were the Quaker couple she referred to in her book.

Coffin's role began to change as the American Civil War approached. He made a trip to Canada in 1854 and visited a community of runaway slaves that lived there. Coffin also helped establish a black orphanage in Cincinnati. As soon as the war broke out in 1861, he and his group began to prepare to help the war wounded. Although he was against the war as a Quaker, he supported their cause. He and his wife spent almost every day in Cincinnati's War Hospital helping tend the wounded. They prepared large buckets of coffee, gave it abundantly to the soldiers, and took many of them home.

Coffin helped form the Western Freedman's Aid Society in 1863 , which offered assistance to the many free slaves. As the soldiers moved south , some of the slaveholders shot their slaves while others left them without food or shelter. The group began collecting food and goods and distributing them to former slaves. Coffin asked the government to establish the Freedment's Bureau to offer assistance to free slaves. Coffin also helped the free slaves set up businesses and educate them after the war. As the leader of society, he traveled to Britain in 1864 to seek help for the slaves freed by the Emancipation Proclamation . His advocacy led to the formation of the Englishman's Freedmen's Aid Society .

Death and legacy

After the war, Coffin raised over $ 100,000 for the Western Freedman's Aid Society , which supported free blacks. The Society provided food, clothing, money, and other aid to the new free slave population in the United States. In 1867 he attended the International Anti-Slavery Conference in Paris . Coffin did not enjoy being in the public eye and saw his job begging for money as demeaning. He noted in his book that if a new leader was found for the organization, he would have liked to give up the position. He was concerned about the generously given money to all blacks, believing that some of them would never be able to fend for themselves unless they were properly educated and farmed. He also believed that society should only give its limited resources to those who could best benefit from them. The society continued its work until 1870, the same year when blacks were guaranteed equality through a constitutional amendment.

With the end of the war, the 15th Amendment was passed and slavery was banned, so that Coffin went into retirement. He later noted in his book that "... I resigned and declared the Underground Railroad to be closed." He spent his final year writing a book about the activities of the Underground Railroad and his life. The book, Reminiscences of Levi Coffin , was published in 1876 and is considered by historians to be the best firsthand account of the organization's activities. Coffin died on September 16, 1877 at 2:30 pm at his home in Avondale, Ohio. His funeral service was held at the Friends Meeting House in Cincinnati. The Daily Gazette reported that the crowd was too large, in the hundreds, to be accommodated, so they had to stay outside. Four of his eight pallbearers were free blacks who had worked with Coffin on the Underground Railroad. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Spring Grove Cemetery , as Quakers do not believe in marked grave sites. On July 11, 1902, African Americans in Cincinnati erected a 6 foot (1.8 m) monument over Coffin's grave in his honor.

Coffin's home in Fountain City, Indiana was purchased by the State of Indiana in 1967 and has been restored to its original state. It is now a National Historic Landmark and is open to the public.

Coffin was first referred to as "President of the Underground Railroad" by a slave catcher who said, "There is an underground railroad operating here and Levi is its president." The salutation was commonly used among other abolitionists. Modern historians estimate that Coffin helped more than 2,000 escaped slaves, although Coffin himself estimated a number around 3,000. Once asked why he was helping slaves, Coffin said, "The Bible commands us to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, but said nothing about color, and I wanted to try to follow the teachings of the Bible." Another time he would simply say, "I thought I was always sure I was doing the right thing."

Biographies

- Martin A. Klein: Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition . Rowman & Littlefield, 2002, ISBN 0-8108-4102-9 ( online ).

- Elaine Landau: Fleeing to Freedom on the Underground Railroad: The Courageous Slaves, Agents, and Conductors . Twenty-First Century Books, 2006, ISBN 0-8225-3490-8 ( online ).

- Loderhose: Legendary Hoosiers: Famous Folks from the State of Indiana . Emmis Books, 2001, ISBN 1-57860-097-9 ( online ).

- Mary Ann Yannessa: Levi Coffin, Quaker: Breaking the bonds of slavery in Ohio and Indiana . Friends United Press, 2001, ISBN 0-944350-54-2 ( online ).

Other literature

- Claus Bernet : Coffin, Levi. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 31, Bautz, Nordhausen 2010, ISBN 978-3-88309-544-8 , Sp. 271-274.

- Levi Coffin: Reminiscences of Levi Coffin . R. Clarke & Co, 1880 ( online [accessed April 30, 2009]).

- Gwenyth Swain: President of the Underground Railroad: A Story about Levi Coffin . Millbrook Press, 2001, ISBN 1-57505-551-1 ( online ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 1.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 2.

- ↑ a b c d Yannessa, p. 3.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 4.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 7.

- ↑ a b c d Yannessa, p. 10.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 11.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 12.

- ↑ a b c d e Loderhose, p. 21.

- ↑ a b c Yannessa, p. 14.

- ↑ Loderhose, p. 20.

- ↑ a b c Yannessa, p. 23.

- ↑ a b c Yannessa, p. 13.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 24.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 16.

- ↑ Yannessa, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ a b c Yannessa, p. 15.

- ↑ a b Klein, p. 98.

- ↑ a b c Yannessa, p. 18.

- ↑ a b c Yannessa, p. 25.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 26.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 27.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 28.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 29.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 30.

- ↑ Landau, pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 31.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 43.

- ↑ Landau, p. 65.

- ↑ Yannessa, pp. 44-45.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 48.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 47.

- ↑ a b c d e Yannessa, p. 50.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 51.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 52.

- ↑ a b Yannessa, p. 54.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 60.

- ↑ Yannessa, p. 36.

Web links

- Levi Coffin's handwritten wants. University of Cincinnati , accessed April 30, 2009 .

- Levi Coffin. Ohio Historical Society, accessed April 30, 2009 .

- Levi Coffin in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Levi Coffin's Underground Railroad Station. Public Broadcasting Service , accessed April 30, 2009 .

- Levi Coffin House. US Department of the Interior, accessed April 30, 2009 .

- Levi and Catharine Coffin. Indiana Historical Society, accessed March 18, 2014 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Coffin, Levi |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American Quaker, abolitionist, and businessman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 28, 1798 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near New Garden, Guilford County , North Carolina |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 16, 1877 |

| Place of death | Avondale , now the neighborhood of Cincinnati , Ohio |