Mactaris

Coordinates: 35 ° 51 ' N , 9 ° 12' E

Mactaris ( Neupunisch Mktʽrm) was an ancient city in the Roman province of Africa Byzacena , about 150 km southwest of Carthage near today's place Maktar ( Arabic مكتر) in Tunisia .

geography

Mactaris is located a good 70 km southeast of El Kef on the edge of a 900 m high plateau that is drained by the Oued Saboun, a tributary of the Medjerda .

history

In the 3rd century BC BC the Numidians built a fortress in the strategically favorable location , which should control the trade routes between Sbeitla , Kairouan and El Kef. The settlement quickly grew into a larger settlement, which under Massinissa developed into a center of Numidia. After the fall of Carthage , numerous Punic refugees poured into Maktar, bringing their culture and skills with them. Buildings, administrative system and language were strongly influenced by Carthaginians. Many Punic inscriptions and figures, but also the remains of temples, bear witness to this.

In 46 BC Ch. Maktar became Roman , but retained the Punic administration and government with the division into sufetes , while the immigrant Romans united in the Pagus . The city's upswing continued. As a transshipment point for grain, olive oil, cattle and textiles and as a traffic junction between Carthage, Sufetula , Thugga and Tebessa , Mactaris grew into one of the richest cities in the province.

It was not until Trajan (97–117) that the city was Romanized . It was given a uniform Roman constitution and the status of a Colonia , which automatically gave all residents Roman citizenship. The unrest of the third century that ushered in the decline of the Roman Empire also affected Maktar. The decline could be stopped again under Diocletian (284-305). Maktar survived the invasion of the Vandals and became an important Byzantine fortress . In late antiquity Mactaris was a diocese, the titular bishopric of Mactaris goes back to this. The Christianization documented in the construction of numerous churches. The devastating raid of the Beni Hilal (1050) led to the final downfall of the city.

Archaeological excavations began by the French in 1914, including with German prisoners of war, and were continued on a large scale from 1944. Although not everything has been uncovered to this day, the ruins are one of the most interesting ancient sites in Tunisia , especially because of its thermal baths and the Schola of the Juvenes .

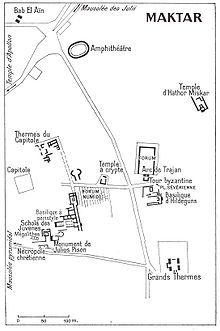

buildings

Forum

The rectangular, paved meeting place was designed for the Roman population in the 2nd century, while the local population had their own forum 50 m to the southwest. The square was surrounded by a portico . The mighty and well-preserved Arch of Trajan stands on its south side.

Arch of Trajan

The Arch of Trajan was built by citizens of the city in AD 116 on the occasion of the granting of Roman citizenship to parts of the local elite of Mactaris under Trajan.

Thermal baths

The great thermal baths are among the best preserved facilities of this type in North Africa. The walls of the frigidarium rise up to 15 m. The building was built around the year 200 AD and is decorated with oriental tendrils on the capitals and with a beautiful floor mosaic .

Schola of the Juvenes

The building complex, begun in 88 AD and completed around the year 200, was the meeting point of the “youth organization”, a kind of militia of young men who performed certain police tasks, especially collecting taxes. In Maktar it consisted of about 70 members. As in other Roman provincial cities, organization played an important role at times. Membership in the strictly managed organization was a prerequisite for entering the high military service. In addition to paramilitary exercises and sport, subjects such as commodity science , finance , political science and culture were on the school curriculum . In the course of time, the brotherhood gained more and more influence, as the wealthy citizens of the provincial cities defended themselves against the power claims of the central government with their help. In 238 she was able to push through the election of Emperor Gordian I against the Emperor Maximinus Thrax elected by the Roman Senate . However, the organization experienced persecution afterwards, and eventually the buildings were demolished and demolished. The Schola was restored under Emperor Diocletian. The original building, known as the basilica , was used as a church in the Christian era, with a Punic sarcophagus from the neighboring necropolis serving as an altar .

literature

-

Research archéologiques Franco-Tunisiennes à Mactar .

- Vol. 1, 1: Gilbert Charles-Picard : La maison de Vénus. 1: Stratigraphies et étude des pavements. 1977.

- Vol. 5: Françoise Prévot: Les inscriptions chrétiennes. 1984.

- Claude Lepelley: Les cités de l'Afrique romaine . 1981, Vol. 2, pp. 289-295.

- Hans-Joachim Aubert: Tunisia . Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-17009231-6 , pp. 239-246.

- Werner Huss : Mactaris. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 7, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01477-0 , column 630 f.

- Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger - Rainer Lukits, Antikes Mactaris and the cutting inscription CIL VIII 11824 (Linzer Archäologische Forschungen, special issue XLII). Linz 2008, ISBN 978-3-85484-590-4