Continental barrier

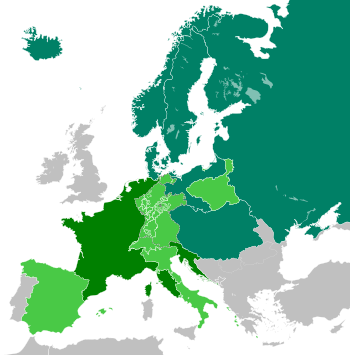

The Continental System ( French blocus continental , English continental system ) was one of Napoleon in the November 21, 1806 Berlin decreed economic blockade on the United Kingdom and its colonies. The import ban on British goods that existed in France as early as 1796 was extended to the continental European states as a result of Napoleon's military victories. Great Britain was to be forced into negotiations with France by means of the economic war and the French economy was to be protected against European and transatlantic competition. The continental barrier existed from 1806 to 1813.

Prehistory (1796–1806)

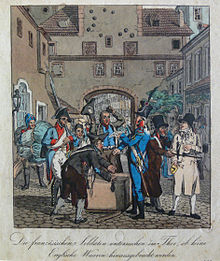

The foundation for Napoleon's economic policy towards England had already been laid by the Directory : A law of October 31, 1796 declared that “goods imported from abroad, wherever they come from” are automatically considered English and may not be imported into France. However, the Directory did not interpret the law as strictly as Napoleon, who did not want to allow any more imports into France. Because of his military conquests, Napoleon was able to enforce the import ban and the confiscation of English goods in occupied territories and states allied with France. In 1803 he let a corresponding embargo come into force in the Italian Republic . Between April 1803 and June 1806 treaties followed with Portugal, Holland, Spain, Naples and Prussia. Since the states did not voluntarily support his trade blockade, Napoleon used the military to control it. On several occasions there were even violent confrontations between French troops and the local population. The Neuchâtel affair , which affects trade with Switzerland, also fell at this time .

Great Britain had already imposed a sea blockade on French port cities in 1793 . In this way France should be cut off from its overseas trade. In the Berlin and Milan decrees, Napoleon justified his continental blockade by stating that Great Britain, in violation of international law, was endangering international merchant shipping and had confiscated private property. However, the naval battle of Trafalgar on October 21, 1805, as a result of which Napoleon dropped his plans to invade Great Britain, became the specific reason for the continental blockade . The only option left to the French emperor was to conquer Great Britain economically. After all, almost a third of British exports and 15% of British industrial production were traded to continental Europe. The British Isles were dependent on grain imports from the Baltic States. Napoleon also hoped to be able to cut the British Navy from its main building material, wood. In fact, Great Britain had so far been able to meet its wood needs with supplies from Russia and the Baltic Sea region. Since the continental barrier, it has mainly sourced wood from Canada.

decisions

Berlin decree of November 21, 1806

The military successes of France in 1806 favored the establishment of a continental barrier: By occupying neutral Hanseatic cities, Napoleon brought the north German coast under his control - the region through which Great Britain conducted most of its European trade. Napoleon had also defeated Prussia in the battle of Jena and Auerstedt . In the Prussian capital Berlin, which was occupied by French troops, Napoleon ordered his continental blockade. The so-called Berlin decree of November 21, 1806 was to be implemented immediately in Spain, the Kingdom of Italy , Holland and the Hanseatic cities.

It consists of two parts: The first part is a “list” of complaints that are intended to justify the 11 articles or the provisions of the continental ban in the second part. In the first part of the Berlin decree, Napoleon claims that the British naval blockade does not differentiate between civilian merchant and military warships. With reference to the right of conquest, the British were only allowed to confiscate state property de jure . Instead, they would not have stopped even at private property. In addition, a naval blockade should be limited to militarily "fortified port cities". Great Britain had taken out the right to block even ports in which no warships were anchored. Even estuaries and long stretches of the French coast are not excluded from the British ram. At the same time, the first part emphasizes that it is in vain to want to encircle France, since Great Britain's forces are not sufficient for this. Of the eleven articles in the second part, Diedrich Saalfeld considers the following to be particularly meaningful:

- The British Isles are in a state of lockdown.

- All trade and correspondence to the British Isles is prohibited.

- With regard to the future absence of English merchants from the continent, it must be emphasized that British nationals are to be arrested by the military authorities and treated as prisoners of war.

- All supplies, magazines and goods coming from England, its factories and colonies, as well as all property belonging to English subjects, are declared a "good prize".

- Any trade in "English" goods is prohibited.

- Half of the income resulting from the confiscation of the goods is reimbursed to the merchants.

- No ship from England or its colonies is allowed to dock in any port.

With the Berlin decree, Napoleon linked, as he himself put it, the hope of "conquering the sea through the power of the land".

Milan decrees of 1807

The Berlin decree was expanded by the Milan decrees of November 11 and December 17, 1807. These decreed that all ships, regardless of the flag they were flying, which had moored in Great Britain or which had submitted to British controls, should be confiscated immediately, including their cargo. The Berlin decree, however, only referred to ships that had cast off from Great Britain immediately before. Up until the Milan decrees, this enabled the legal trade of British goods via Scandinavian or US ships. The Milan decrees were also a reaction to a British decree of November 11, 1807, which, as a countermeasure to the Berlin decree, was intended to affect maritime trade with France: neutral merchant ships first had to dock in England and pay a tax before they could sail to France. Appropriate customs duties had to be paid before and after the stay in France; 25% each on the value of the freight. The British decree also extended the naval blockade to states that were allied with France during wartime.

Decrees of Saint-Cloud and Trianon

Over time, the continental barrier added to tensions with both the United States and the French population. Napoleon responded to this in 1810 with the decrees of Saint-Cloud and Trianon. Under certain conditions he allowed the import of British colonial goods such as coffee, cotton and sugar to France again. The decree of Saint-Cloud, issued in July 1810, stipulated that shipowners and traders could obtain licenses for a high payment to the French state. Even in areas annexed by France such as the former Kingdom of Holland and the Hanseatic cities, limited trade with Great Britain could be carried out in this way. However, this involved strict controls. If no corresponding licenses were issued, as the decree of Trianon which followed in August 1810 determined, the goods could still be legalized with customs duties. It was also possible to pay this duty in the form of taxes in kind , which were then resold on the markets in France. The duty on colonial goods introduced by the Trianon Decree was 40–50% of the value of the goods, including US products. This also served to equalize prices between France and other European countries, because outside France, colonial goods were usually sold at lower prices. The Trianon decree created a uniform customs regulation for colonial goods and cotton on the continent. One advantage of the special provisions of Saint-Cloud and Trianon from the point of view of European countries was additional income from the customs duties that would otherwise have flowed into smuggling. However, the authorization of French grain exports to Great Britain, which was also laid down in the decrees, undermined the actual function of the continental barrier. In addition, the prices for colonial goods remained too high due to the tariffs imposed, which continued to damage the French economy.

Implementation and effectiveness

To control the continental blockade, Napoleon sent French customs officers to occupied or neutral states. In 1806 a customs line was created from the Rhine in the Kingdom of Holland to the north German coast to Travemünde. In July 1809, a customs line was also set up from Cuxhaven along the Lower Weser to Rees on the Rhine . 40 French customs officers were deployed on this route between Bremen and the mouth of the Weser. A customs officer was responsible for about two kilometers.

French troops marched in for additional security; first in the Duchy of Mecklenburg in November 1806 and then in Swedish Pomerania in July 1807. In 1808, the coastal region near Rome was incorporated into the French state. In some cases, British goods were even burned to the public. The most impressive incident after Roger Dufraisse occurred in Frankfurt am Main in 1810. Frankfurt controlled the smuggling trade in British goods to south-western Europe, which Napoleon did not miss. On November 8, 1810, he ordered the burning of all British manufactured goods there as a deterrent. However, only about 10% of these goods, valued at 800,000 guilders, ended up in the flames, as the French agents proved to be corruptible. A total of four large burnings took place on the Frankfurt Fischerfeld between November 17 and 27, 1810. Implementation at sea proved to be even more difficult than within inland Europe: After the Battle of Trafalgar, Napoleon no longer had a sufficiently large fleet to "cordon off" the continent's extensive coastline. Heligoland in particular benefited from this development . The island was occupied by Great Britain in 1807 and became an important center for smuggling. In 1807, only four traders conducted their business on Heligoland, in 1813 there were more than 140. In 1814 - after the continental blockade ended - their number fell to eight. In addition to the British merchants, the names of Hamburg traders who had warehouses built on Heligoland have also come down to us.

The effectiveness of the continental barrier varied between northern and southern Europe. The presence of French troops on the North and Baltic Seas enabled smuggling to be prevented more effectively than in the Mediterranean region. There the British had naval bases on Malta and Gibraltar, but also on Sardinia and Sicily, from which the continental barrier could be infiltrated. Before the continental blockade, Great Britain exported roughly twice as many goods to Central and Western Europe as to the Mediterranean region. During the continental blockade, however, the export volume with the Mediterranean countries quadrupled. British exports to northern European countries were only 1: 5 in relation to the Mediterranean area. With the French campaign in Spain from 1808, another hole appeared in the continental barrier.

Consequences for trade

The continental blockade had conflicting consequences for trade. Not all sectors of the economy were either affected or favored equally. In Great Britain imports of goods from the colonies remained unaffected, while there were shortages in the textile and wood supply. France lost economic access to its colonies. As a result, the sugar refineries, for example, died. On the other hand, the elimination of English competition in the French cotton industry led to an upswing. In the short term, France benefited from the continental blockade. The loss of English competition initially actually forced the states in the French sphere of influence to purchase French goods. The Napoleonic wars, however, caused the potential buyers to become indebted and thus a decline in French sales. In addition, the French colonial trade collapsed due to the British naval blockade. In 1810/1811 there was a severe economic crisis, which should contribute to the decline of the French Empire.

The consequences of the continental block differed not only between states, but also between individual economic sectors and regions. While the overseas -oriented businesses suffered, the domestic market benefited. Exports shifted from important port cities like Hamburg to smaller ports, where fewer controls were carried out and thus better conditions for smuggling prevailed. The major trade fairs in Leipzig and Frankfurt am Main also suffered heavy losses. As the contributions raised by the French occupiers reduced the purchasing power of the population, the demand for luxury goods, which were the main attraction of trade fairs, declined.

Great Britain

The claim of Article I of the Berlin Decree, namely the imposition of a state of blockade on the British Isles, could only be implemented rudimentarily. France did not have the naval strength necessary to cut off Britain from its colonies or to deny the country access to the world's oceans. The continental block was de facto limited to parts of Europe. In contrast to France, Great Britain was able to expand its colonial empire as a sea power. It added the Cape Verde Islands , some islands in the Pacific and all of India. Despite its colonial possessions and dominance of the world's oceans, Britain's trade balance was not entirely unaffected by the continental blockade. Between the years 1781 and 1802 the country was able to increase its goods exports by an average of 6.4% per year. Between 1802 and 1814 the export rate only grew by an average of 3.4% per year. This decline was not only due to the continental lock. Participation in the Napoleonic Wars also put the British economy under pressure. Overall, there was a shift in the British export market, with South and Central America growing in importance. Between 1808 and 1814, the British export volume there roughly corresponded to that to the United States of America. But even to continental Europe, trade never completely broke off.

The British Isles' dependence on grain from continental Europe was particularly problematic. The longer transport from Eastern Europe caused wheat prices to triple. Hunger riots were the result. The continental lock also contributed to a devaluation of the pound sterling . Between 1808 and 1810 the British currency lost 15% of its value compared to the French franc and the Hamburg shilling. The resulting inflation mainly hit the economically weaker social classes in Great Britain. Due to the mechanization of weaving mills in particular, they were acutely threatened with unemployment and affected by low wages. This made them vulnerable to strike movements. In the Manchester county, 60,000 cotton workers stopped working in 1808. Burns and factory storms were so frequent that the British Parliament passed a law punishing the destruction of machines with death. Eighteen machine strikers were executed in Yorkshire alone .

From 1810 to 1814 Napoleon loosened his continental barrier. He saw controlled smuggling as an opportunity to ruin Britain's economy. As a supporter of the theory of bullionism , Napoleon assumed that Britain would get into a severe economic crisis if only enough gold reserves were to leave the island. In order to achieve this goal, the French state opened the ports of Dunkirk and Gravelines to English smugglers, who acquired the relevant licenses. The English smugglers brought gold to France with their payment, which was primarily intended to finance Napoleon's costly campaign on the Iberian Peninsula. Up to 300 smugglers bought French textiles, brandy and gin in Gravelines. In addition, as early as 1809, both the French and British governments were ready to allow legal trade between the two countries in exceptional cases. After the bad harvest of 1809, Great Britain was urgently dependent on French grain imports. Conversely, during the severe economic crisis of 1810, the French government must have had an interest in alleviating the shortage of colonial goods and raw materials. This was also expressed in the decrees of Saint-Cloud and Trianon, already mentioned .

Significance for German industrialization

The continental barrier is seen by many historians as one of the prerequisites for early industrialization in the German states. Above all, the mechanized cotton industry in Saxony and the Rhineland benefited from the elimination of British competition. Between 1806 and 1813 the number of cotton processing companies in Saxony increased twenty-fold. The cloth industry around Liège, Aachen and Leiden also received new impulses. The demand for wool, which was previously mainly imported from Great Britain, was covered by breeding merino sheep in Saxony and Silesia. In addition, the numerous soldiers called up had to be provided with clothing. In addition to the textile industry, the armaments and iron industries also benefited.

The decline in British manufactured goods on the continent also favored innovations in mechanical engineering. Above all, the newly created mechanized weaving mills needed spindles and machines to drive them. This led to the establishment of several factories, including by Johann Georg Bodmer in the former St. Blasien monastery . Outside the textile sector, Georg Christian Carl Henschel in Kassel and Friedrich Krupp in Essen founded factories during the continental blockade. Although the demand for cast steel was still low at that time, the absence of British competition offered Friedrich Krupp enough incentives to imitate it experimentally. On November 20, 1811, he founded a cast steel factory.

To compensate for the decline and high prices of British colonial goods and raw materials, chemists, technicians and pharmacists on the continent worked on plant substitutes. Coffee beans should be replaced with chicory powder , cane sugar with sugar beets and the blue dye indigo with woad . In France and Germany in particular, this created the basis for a later chemical industry. Although it was known as early as the middle of the 18th century that sugar could be obtained from beetroot , there was no significant need to cultivate the native crop before the continental barrier. In particular, the French colony of Saint-Domingue supplied the continent with cane sugar. However, during a slave revolt , the colony managed to shake off French rule and declare itself independent. As a result, the sugar trade on the continent collapsed. A number of scientists tried to respond to the shortage of sugar. This also included Franz Carl Achard , who was able to increase the sugar content of beet considerably through breeding. Napoleon also heard of such successes. In a decree of March 25, 1811, he ordered the cultivation of sugar beet in France on an area totaling 32,000 hectares. Six experimental schools were supposed to supervise and improve the processing. In 1812 there were 150 sugar beet factories in France. While sugar beet production in the German states became unprofitable after the end of the continental blockade, they were able to hold their own in France thanks to a new protective tariff.

One of the negative effects of the continental blockade, however, is the fact that the German states lost contact with the industrially most advanced state in Europe. In terms of the level of technical development, Great Britain increased its lead.

The continental barrier was not the only requirement that favored industrialization in Germany. Above all, the territorial reorganization of Germany and state reforms played a role here. In the Napoleonic era, for example, numerous internal customs borders ceased to exist and larger economic units emerged. Other reasons are the standardization of dimensions and weights and the introduction of the freedom of trade .

The cause of Napoleon's Russian campaign

The continental blockade was one of the causes that led to the Russian campaign of 1812 . The tsarist empire was economically dependent not only on the export of wood, grain and hemp, but also on the import of British colonial and industrial goods. The Russian currency lost 25% of its value as a result of the continental blockade. Above all, the Russian aristocracy, which could barely afford luxury products like coffee and export very few goods from their country estates, put the tsar under pressure to change its foreign trade policy towards France.

The pretext for such a change of course finally provided the decree of Fontainebleau, enacted in 1810, in which Napoleon prescribed the practice of destroying illegal goods from Great Britain. Only a few weeks later, the tsar responded with a decree. He was able to do this because Napoleon recognized Russia as an equal ally in the Peace of Tilsit . On this basis, the Tsar agreed to join the continental blockade. However, the tsar was no longer bound by this promise. In the decree of December 31, 1810, the tsar legalized ship trading under a neutral flag in British goods in Russia. At the same time, French luxury goods were subject to high customs duties. The British cargo reached the German states from Russia, which finally led to the continental blockade being reduced to absurdity . Napoleon then incorporated the Hanseatic cities and the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg into the French state in order to maintain the continental barrier with direct control over the north German coast. Since the Grand Duke of Oldenburg, who was dethroned, was a relative of the Tsar, relations between Paris and Saint Petersburg deteriorated further.

Research subject

Conceptual debate

In 1965, the French historian Marcel Dunan founded the research debate in a paper to the Académie des sciences morales et politiques as to whether a distinction had to be made between the concepts of the continental blockade and the continental system in Napoleonic economic policy . According to Dunan, the concept of the continental blockade could only mean the closure of the continental European market for British goods, while the continental system was intended to give France a monopoly in European trade and industry. The American historian Katherine Aaslestad also supports the distinction between the two terms. She emphasizes that the continental system refers to the political organization of the continental blockade. This would include measures such as the drawing of borders in northern Germany or the reinforcement of the French customs authorities in Hamburg. She understands the continental blockade as the economic war against Great Britain itself. The historian Elisabeth Fehrenbach supplements this definition of the continental system: The term continental system should not only mean implementing measures for the continental barrier, but also the opening of the European market for French goods. For this purpose, Napoleon used trade agreements with other European states. For example, in early 1808 the Kingdom of Naples had to agree to only import French cotton.

According to Roger Dufraisse, the continental barrier and the continental system are supplementary to one another. Both concepts can be traced back to ideas of the French Revolution , which Napoleon took up again. Both the continental blockade and the continental system should, according to Dufraisse, give France's economy priority over all other European countries. The continental system should remove barriers to trade in French goods in continental Europe and facilitate French access to the continent's mineral resources and food reserves. Above all, the English products, which dominated the continental European trade, had to be replaced by French goods. The continental barrier supplemented the continental system here, as Napoleon did not succeed in defeating England militarily. The continental European countries should therefore join the French import ban on English goods. Napoleon hoped to be able to damage English trade and industry to such an extent that the English government would have to start negotiations with France. Eberhard Weis does not consider the distinction between the terms continental barrier and continental system to be sensible. According to him, the "système continental" or the continental system is also used in contemporary sources for the continental barrier.

literature

- Katherine B. Aaslestad, Johann Joor (eds.): Revisiting Napoleon's Continental System. Local, Regional and European Experiences (War, Culture and Society, 1750-1850). Basingstoke 2015.

- Roger Dufraisse : The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35-44.

- Diedrich Saalfeld: The continental barrier. In: Hans Pohl (ed.): The effects of tariffs and other trade barriers on the economy and society from the Middle Ages to the present. Stuttgart 1987, pp. 121-139.

- Helmut Stubbe da Luz : Occupants and Occupied. Napoleon's governor regime in the Hanseatic cities. Volume 2: Continental barrier - Occupatio pacifica - Assimilation policy. Munich 2005.

- Elisabeth Vaupel : Napoleon's continental blockade and its consequences. The boom in substitutes. In: Chemistry in our time 40, Weinheim an der Bergstrasse 2006, pp. 306-315.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35–44, here SS 36–38.

- ^ Brandt: The Wars of Liberation from 1813 to 1815 in German History . In the S. (Ed.): On the threshold of modernity. Germany around 1800 . 1999, pp. 83–115, here p. 87.

- ^ Diedrich Saalfeld: The continental barrier . In: Hans Pohl (ed.): The effects of tariffs and other trade barriers on the economy and society from the Middle Ages to the present . Stuttgart 1987, pp. 121-139, p. 121.

- ^ Brandt: The Wars of Liberation from 1813 to 1815 in German History . In the S. (Ed.): On the threshold of modernity. Germany around 1800 . 1999, pp. 83–115, here p. 117.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: Napoleon. Revolutionary and monarch. A biography . Munich 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Elisabeth Vaupel: Napoleon's continental barrier and its consequences. The boom in substitutes . In: Chemistry in our time , 40. Weinheim an der Bergstrasse 2006, pp. 306–315, here: p. 307

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel : The transformation of the world: a story of the 19th century . Munich 2009. p. 549.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: Napoleon. Revolutionary and monarch. A biography . Munich 1994, p. 107.

- ↑ Helmut Stubbe da Luz: Occupants and Occupied. Napoleon's governor regime in the Hanseatic cities . Volume 1: Model Construction - Prehistory - Occupatio bellica . Munich 2005, pp. 585-586.

- ^ Diedrich Saalfeld: The continental barrier . In: Hans Pohl (ed.): The effects of tariffs and other trade barriers on the economy and society from the Middle Ages to the present . Stuttgart 1987, pp. 121-139, p. 122.

- ^ Frank Bauer: Napoleon in Berlin. Prussia's capital under French occupation 1806-1808 . Berlin 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ Rejoinder to His Britannic Majesty's order in council of the 11th of November. 1807

- ^ Diedrich Saalfeld: The continental barrier . In: Hans Pohl (ed.): The effects of tariffs and other trade barriers on the economy and society from the Middle Ages to the present . Stuttgart 1987, pp. 121-139, p. 123.

- ↑ Reinhard Stauber: The year 1809 and its prehistory in Napoleonic Europe . In: Brigitte Mazohl, Bernhard Mertelseder (Ed.): Farewell to the fight for freedom? Tyrol and '1809' between political reality and transfiguration . Innsbruck 2009, pp. 13–26, here; P. 24.

- ^ Helmut Stubbe-da Luz : French Period in Northern Germany (1803-1814): Napoleon's Hanseatic Departments . Bremen 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach : From the Ancien Régime to the Congress of Vienna . Munich 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Helmut Stubbe-da Luz: French Period in Northern Germany (1803-1814): Napoleon's Hanseatic Departments . Bremen 2003, p. 134.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach : From the Ancien Régime to the Congress of Vienna . Munich 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35–44, here SS 39.

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach : From the Ancien Régime to the Congress of Vienna . Munich 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35–44, here SS 40.

- ↑ Helmut Stubbe da Luz : Occupants and Occupied. Napoleon's governor regime in the Hanseatic cities . Volume 2: Continental barrier - Occupatio pacifica - Assimilation policy. Munich 2005, p. 118

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35–44, here SS 40.

- ^ Leoni Krämer: Continental barrier. In: Rainer Koch (Hrsg.): Bridge between the peoples - To the history of the Frankfurt fair . Volume III: Exhibition on the history of the Frankfurt trade fair . 1991, pp. 343-346, here; SS 344.

- ^ Elisabeth Vaupel: Napoleon's continental barrier and its consequences. The boom in substitutes . In: Chemistry in our time , 40. Weinheim an der Bergstrasse 2006, pp. 306–315, here: p. 307

- ↑ Margrit Schulte Beerbühl: German merchants in London, world trade and naturalization 1660-1818 , Oldenbourg, Munich 2007, pp. 216-217.

- ^ Réka Juhász: Protection and Technology Adoption: Evidence from the Napoleonic Blockade In American Economic Review 108 (11): 3339-76, here 3349.

- ↑ Michael North : The effects of the continental barrier on northern Germany and the Baltic Sea region . In: A. Klinger, H.-W. Hahn, G. Schmidt (Ed.): The year 1806 in a European context. Balance, hegemony and political cultures. Köln-Weimar-Wien 2008, pp. 135–148, here p. 135.

- ↑ Winfried Reiss: Microeconomic Theory. Historically sound introduction . Munich 1990. p. 55.

- ↑ Michael P. Zerres, Christopher Zerres: Development of world trade in the 19th century . Volume 56. Munich / Mering 2008, p. 21

- ↑ Kevin H. O'Rourke: The Worldwide Economic Impact of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1793-1815 . In: Journal of Global History , 1, 2006, pp. 123–49, here p. 125 (Cambridge).

- ↑ Winfried Reiss: Microeconomic Theory. Historically sound introduction . Munich 1990, p. 55.

- ^ Lance E. Davis, Stanley L. Engerman: Naval Blockades in Peace and War, An Economic History since 1750 . New York 2006, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Winfried Reiss: Microeconomic Theory. Historically sound introduction . Munich 1990. p. 55.

- ^ Gavin Daly: Napoleon and the City of Smugglers, 1810-1814 . In: Historical Journal , L / 2 (2007), pp. 333–352, here p. 338.

- ↑ Adam Zamoyski, Phantoms of Terror. Fear of the Revolution and the Suppression of Freedom, 1789–1848 . Beck, Munich 2016, p. 100.

- ↑ Owen Connelly: The French Revolution and Napoleonic Era (special edition). Harcourt College Publishers, New York 2000, p. 233.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : History of the West . Volume 1: From the beginnings in antiquity to the 20th century . Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2009, pp. 411-412.

- ^ Gavin Daly: Napoleon and the City of Smugglers, 1810-1814 . In: Historical Journal , L / 2, 2007, pp. 333–352, here pp. 332 and 338–339.

- ^ Gavin Daly: Napoleon and the City of Smugglers, 1810-1814 . In: Historical Journal , L / 2, 2007, pp. 333–352, here p. 337.

- ↑ Reinhard Stauber: The year 1809 and its prehistory in Napoleonic Europe . In: Brigitte Mazohl, Bernhard Mertelseder (Ed.): Farewell to the fight for freedom? Tyrol and '1809' between political reality and transfiguration . Innsbruck 2009, pp. 13–26, here; P. 24.

- ↑ Michael P. Zerres, Christopher Zerres: Development of world trade in the 19th century . Volume 56. Munich / Mering 2008, pp. 21-22

- ↑ Hubert Kiesewetter: The industrialization of Saxony. A regional comparative explanatory model . Stuttgart 2007, p. 391

- ^ Lothar Gall : Krupp. The rise of an industrial empire . Berlin 2000, p. 19

- ^ Elisabeth Vaupel: Napoleon's continental barrier and its consequences. The boom in substitutes . In: Chemistry in our time , 40, Weinheim an der Bergstrasse 2006, pp. 306-315

- ^ Elisabeth Vaupel: Napoleon's continental barrier and its consequences. The boom in substitutes . In: Chemistry in our time , 40. Weinheim an der Bergstrasse 2006, pp. 306–315, here: p. 312

- ^ Uwe Wallbaum: The beet sugar industry in Hanover. On the origin and development of an agriculturally bound branch of industry from the beginnings to the beginning of the First World War . Stuttgart 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Elisabeth Vaupel: Napoleon's continental barrier and its consequences. The boom in substitutes . In: Chemistry in our time , 40. Weinheim an der Bergstrasse 2006, pp. 306–315, here: p. 313

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn: Reforms, Restoration and Revolution, 1806–1848 / 9 . In: Gebhardt's Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte , Volume 14. 10. Edition. Stuttgart 2010. p. 188.

- ↑ Reinhard Stauber: The year 1809 and its prehistory in Napoleonic Europe . In: Brigitte Mazohl, Bernhard Mertelseder (Ed.): Farewell to the fight for freedom? Tyrol and '1809' between political reality and transfiguration . Innsbruck 2009, pp. 13–26, here; P. 24.

- ^ Adam Zamoyski : 1812. Napoleon's campaign in Russia , trans. by Ruth Keen and Erhard Stölting. Munich 2012, pp. 87-88.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35-44, here p. 39.

- ^ Adam Zamoyski : 1812. Napoleon's campaign in Russia , trans. by Ruth Keen and Erhard Stölting. Munich 2012. p. 90.

- ↑ Jean Tulard : Napoleon or the Myth of the Savior. A biography . Wunderlich, Tübingen 1978, p. 239.

- ↑ Katherine Aaslestad: Introduction: Revisiting Napoleon's Continental System. Consequences of Economic Warfare . In: dies., Johan Joor (Ed.): Revisiting Napoleon's Continental System. Local, Regional and European Experiences . Basingstoke 2014, p. 4

- ^ Elisabeth Fehrenbach: From the Ancien Régime to the Congress of Vienna . Munich 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse: The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries . Göttingen 1984, pp. 35-44, here p. 41.

- ^ Roger Dufraisse : The hegemonic integration of Europe under Napoleon I. In: Helmut Berding (Hrsg.): Economic and political integration in Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. Göttingen 1984, pp. 35-44, here pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Eberhard Weis: Montgelas Eine Biographie 1759-1838 . Munich 2008, pp. 647-648.