Manifesto of the Sixteen

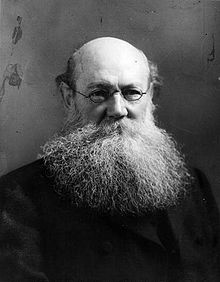

The Manifesto of the Sixteen ( French : Manifeste des seize ) was a document written in 1916 by the well-known anarchists Peter Kropotkin and Jean Grave , which advocated an Allied victory over Germany and the Central Powers in World War I. After the outbreak of the war, Kropotkin and other colleagues campaigned for their point of view in the London magazine Freedom , which in turn led other anarchists to sharply critical replies. In the further course of the war, anarchists participated in anti-war movements across Europe and denounced the war in pamphlets and declarations, as in a declaration in February 1916, which was signed by well-known anarchists such as Emma Goldman and Rudolf Rocker .

The manifesto was drafted by Peter Kropotkin and Jean Grave and signed by 13 other anarchists. Kropotkin and the undersigned saw the armed forces of German imperialism as a threat to the world's workers and decided that they must be defeated. This broke with the anarchist tradition of anti-militarism and the general opposition in the anarchist movement to every party in international military conflicts, which is expressed , for example, in desertion . The positioning of the manifesto brought strong criticism from the signatories, including an allegation of betrayal of anarchist principles.

The document is named after the original number of signatures. The place where one of the signatories stated "Hussein Dey" was wrongly interpreted as a signature, so that instead of the 15 signatories, 16 were counted. The manifesto was first published in La Bataille magazine.

background

Kropotkin's anti-German attitude

Anti-German sentiments were widespread in the anarchist movement in Russia from the very beginning because of German influence over the Russian aristocracy and especially the ruling Romanov dynasty . The historian George Woodcock argued that as a Russian, Kropotkin had been influenced all his life by this mood, which resulted in staunch anti-German prejudice during the First World War. Kropotkin was also influenced by his fellow Russian anarchist Michael Bakunin , who in turn had found such attitudes through his rivalry with Karl Marx . The successes of the Social Democrats , which undermined the revolutionary movements in Germany and the emergence of Wilhelmine imperialism under Otto von Bismarck , further contributed to the hostile attitude towards the German Empire. Woodcook mentioned that Kropotkin denounced the growth of the Marxist movement as a "German idea" and instead exaggerated the French Revolution , what Woodcock called "a kind of adoptive patriotism" .

After the attack in Sarajevo , Kropotkin was suspected of instigating the murderers and was arrested. While in prison, he was interviewed for an article that was due to appear in The New York Times on August 27th . The article, in which he was described as a "veteran Russian agitator and democrat," quoted Kropotkin as being optimistic about the new outbreak of war and convinced that he would ultimately have a liberating influence on Russian society. In a letter that Kropotkin sent to Jean Grave in September of the same year , he scolded him for his desire for a peaceful solution to the conflict and insisted that the war must be fought to the end “ so that the victor can determine the terms of peace . "

Months later, Kropotkin allowed a letter he had written to appear in Freedom magazine , which appeared in the October 1914 issue. Under the heading “A letter for Stefan” he explained his arguments for participating in the war and emphasized that the presence of the German Empire had hindered the development of the anarchist movement throughout Europe and that the German population was just as responsible for the outbreak of war the German state. Kropotkin went on to say that after the victory he expected a radicalization and unification of the Russian people, which would prevent the Russian aristocracy from benefiting from it. So are general strike and pacifism is not necessary and should be pursued the war until the German defeat. The Bolsheviks quickly made political capital out of it. In 1915 Lenin published the article On the National Pride of the Great Russians , in which he attacked Kropotkin and the Russian anarchists in their entirety for the early pro-war attitudes and described Kropotkin and another political opponent, Georgi Plekhanov , as " opportunist or spineless chauvinists ". In other speeches and essays from the early war years, Lenin referred to Kropotkin as a “ bourgeois ” in order to later downgrade him to a petty bourgeois .

Kropotkin suffered from poor health from 1915 to 1916, which he spent in Brighton , England . He was unable to travel during the wintertime and had two chest operations in March. This had the effect that he had to spend most of his time in bed in 1915 and in some kind of wheelchair in 1916. During this time, Kropotkin continued to correspond with other anarchists such as Marie Goldsmith . Other Russian anarchists, Goldsmith and Kropotkin, argued frequently in the spring of 1916 over their views on World War I , the role of internationalism during the conflict, and the possibilities of anti-militarism during this period. Kropotkin took a pro-war position in his correspondence and was receptive to the frequent criticism of the German Reich.

Anarchist Response to World War I and Kropotkin

“It is very painful for me to contradict an old and beloved friend like Kropotkin, who has done so much for anarchism. But precisely for the reason that Kropotkin is so loved and respected by all of us, it is necessary to let him know that we do not follow his remarks about the war. "

At the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, anarchist activity in Europe was limited by external circumstances and the internal division over the war question. The November 1914 edition of Freedom published articles in support of the Allies, including articles by Kropotkin, Jean Grave, and Warlaam Cherkesoff, and Errico Malatesta's “Anarchists Forgot Their Principles,” a refutation of Kropotkin's letter to Stefan .

In the weeks that followed, Freedom received numerous letters which criticized Kropotkin and which, because of the impartiality of the editor Thomas Keell , were published in sequence. Kropotkin responded to this criticism by getting angry with Keell and accusing him of cowardice and declaring that he was not worthy of the role of editor. A meeting was called by members of Freedom , who supported Kropotkin's position and called for the magazine not to appear. Keell was the only invited opponent of the war and rejected the request. The meeting ended in hostile disagreement. As a result, Kropotkin's ties to Freedom ended and the magazine was published as an organ of the anti-war majority of Freedom members.

In 1916 the First World War lasted for over two years, the anarchists were part of the peace movements across Europe and published countless anti-war declarations in left and anarchist publications. In February 1916, a statement was issued by an anarchist congregation that had participants from various regions including England, Switzerland, Italy, the United States, Russia, France and the Netherlands. The document was signed by figures such as Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis , Emma Goldman , Alexander Berkman , Luigi Bertoni , Saul Janowsky , Harry Kelly , Thomas Keell, Lilian Wolfe , Rudolf Rocker and George Barrett and supported by Errico Malatesta and Alexander Schapiro , two of the three secretaries the Anarchist International of 1907. In this paper, the perspective was elaborated that all wars are the result of the prevailing social order and that no individual governments are to blame, and that wars of aggression and wars of defense do not in principle represent different situations. All anarchists were urged to support only class struggle and the liberation of the population from oppression as a means of ending interstate wars.

As a result of their increasing isolation from the majority of antiwar anarchists, Kropotkin and his supporters drew closer together in the months leading up to the manifesto. Some of these supporters later signed the manifesto, including Jean Grave, Charles Malato, Paul Reclus, and Christiaan Cornelissen.

The manifest

Concept and authors

Since Kropotkin could not travel in 1916, he corresponded a lot, including with Jean Grave, who visited him from France with his wife. They discussed the war and Kropotkin's strong support for it. On Kropotkin's suggestion that as a younger man he would have liked to have been a fighter, Grave suggested that a document be published encouraging the anarchists to support the Allied efforts in the war. Kropotkin hesitated due to his own physical unfit for active military service, but was persuaded by Grave.

Exactly what role the two played as authors is not known. At the time, Grave said he wrote the manifesto, which Kropotkin edited. Grigory Maximov reported that Kropotkin wrote the script and Grave made minor changes. George Woodcock pointed out that the work was shaped by Kropotkin's known concerns and his arguments against the German Reich and so the exact authorship did not matter.

Release history

The manifesto , which was later so named, dated February 28, 1916 and was first published on March 14 in La Bataille magazine. La Bataille was a controversial socialist magazine known for its support for the war and therefore accused by Marxist groups of being a front line for government propaganda. The manifesto was later republished on April 14, 1916 in the London magazine Freedom and in the Libre Fédération in May 1916, in Lausanne , Switzerland . The Libre Fédération version had additional signatories who joined the call after it was first published.

content

The original statement was ten sections long and included philosophical and ideological standpoints based on the views of Peter Kropotkin.

The essay begins by stating that the anarchists would have acted correctly in resisting the war from the start, and that the authors would prefer peace enforced by an international conference of European workers. It is also argued that the German workers would most likely also support an end to the war and give some reasons why a ceasefire would be in the best interests of the German workers. The reasons they gave were that after 20 months of war the citizens would understand, that they were deceived about the nature of the war and that they were not waging a defensive war ; that they would recognize that the German state had been preparing for such a conflict for some time and was therefore inevitably wronging; that the German Reich could not logistically supply the occupied territories; and that people in the occupied territories could choose whether to affiliate.

“We feel deep in our conscience that the German attack is not only a threat to our hopes for emancipation, but also a threat to the whole of human evolution. That is why we, anarchists, we, anti-militarists, we, opponents of war, we, passionate fighters for peace and brotherhood among the people, sided with the resistance and believe that we must not isolate ourselves from the fate of the population. "

In several sections, the authors describe possible conditions for a ceasefire and reject the idea that the German Reich can dictate the conditions of peace. In addition, the authors insist that the German population has to accept some responsibility for not having resisted the German government's entry into the war. However, the authors do not consider an immediate call for peace negotiations to be advantageous because the German state could dictate the conditions through its military and diplomatic strength. Instead, the manifesto proclaims that the war must continue until the German state has lost its military strength and, moreover, its bargaining power.

The authors also proclaim that as a result of their anti-government, anti-militarist and internationalist philosophy, war support means an act of resistance against the German Reich. The manifesto concludes that the victory over Germany and the overthrow of the Social Democratic Party of Germany and other ruling parties in the German Reich would promote the anarchist goals of the emancipation of Europe and the German people, and that the authors are ready to draw closer to the Germans this goal to work together.

Signatories and supporters

The manifesto was signed by some of the most important anarchists in Europe of the time. The signatories were initially fifteen; Hussein Dey was incorrectly counted as sixteenth . However, the city of Hussein Dey , which later became a district of Algiers , was only the then residence of Antoine Orfila and therefore appeared on the manifesto. Jean Grave and Peter Kropotkin were the co-authors of the manifesto , with Grave suggesting the writing. Grave claimed to be the main author of the manifesto , although most of the ideas came from Kropotkin's earlier published articles on war.

In France, the anarcho-syndicalist Christiaan Cornelissen and François Le Levé were among the signatories; Cornelissen was a supporter of the Union sacrée , an agreement to suspend the disputes between the French government and the trade unions, in favor of national defense in World War I, and wrote several anti-German brochures, during the 32-year-old Le Levé later in the Resistance in World War II fought. Another French signatory was Paul Reclus , the son of the well-known anarchist Élisée Reclus , whose support for the war and the manifesto also convinced the Japanese anarchist Sanshirō Ishikawa to sign (who was living with Reclus at the time). Ishikawa signed the document as "Tchikawa".

Varlam Cherkezishvili (in the Russian form as "Varlaam Tcherkesoff" signed), a Georgian anarchist, critic of Marxism and journalist was another important signatories. The other signatories of the Manifesto of the Sixteen were Henri Fuss , Jacques Guérin , Charles-Ange Laisant , Charles Malato , Jules Moineau , Antoine Orfila , Marc Pierrot and Ph. Richard. James Guillaume was a supporter of the war but, for reasons unknown, was not a signatory to the original manifesto . The manifesto was ratified and supported by about a hundred anarchists, of which Italian anarchists made up about half.

effect

“The anarchists themselves owe it to themselves to protest against this attempt to associate anarchism with the continuation of a cruel slaughter that never promised to be of any benefit to the cause of justice and freedom and which is now also from the standpoint of the leaders shows both sides as absolutely useless. "

The international anarchist movement met the publication of the manifesto with great rejection, and in assessing its impact George Woodcock wrote that it "merely confirmed the already existing split in the anarchist movement." Where the signatories of the manifesto the First World War as a struggle between Germans Imperialism and the international working class, most contemporary anarchists, including Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman , saw the First World War as a war between different capitalist-imperialist states at the expense of the working class. While Kropotkin and his like-minded people reached a hundred people at most, the overwhelming majority of anarchists spoke out against the war.

To accompany the reprint of the manifesto in Freedom magazine in April 1916, a reply from Errico Malatesta was printed. (Dt about.: Malatesta response entitled "Governmental Anarchists" government anarchists ) recognized the "good faith and good intentions" of the signatories but accused them of betraying the anarchist principles. Malatesta was joined by the charges of others such as Luigi Fabbri , Sébastien Faure , and Emma Goldman:

“We decided to reject Peter [Kropotkin] 's stance, and luckily we were not alone. Many others thought, as we did, unfortunate as it was to turn against a man who had been an inspiration to us for so long. Errico Malatesta showed far greater understanding and coherence, and with him were Rudolf Rocker , Alexander Schapiro, Thomas H. Keell, and many other local and Yiddish-speaking anarchists in Britain.

In France, Sébastien Faure, A. Armand (E. Armand? - ed.) And members of the anarchist and syndicalist movement, in the Netherlands Domela Nieuwenhuis and his comrades took a stand against this murder on a large scale.

In Germany Gustav Landauer , Erich Mühsam , Fritz Oerter, Fritz Kater , and many other comrades remained sane.

Of course we were only a handful compared to the war-intoxicated millions, but we managed to spread a manifesto from our International Bureau around the world and we now revealed the true nature of militarism with increased energy at home. "

Because of his staunch support for the war, Kropotkin's popularity dwindled and many former friends broke up with him. Two exceptions were Rudolf Rocker and Alexander Schapiro, but both were serving prison terms at the time. As a result, Kropotkin was increasingly isolated during his final years in London before returning to Russia. In Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas of 1922, an overview of the Kroptkin works of Camillo Berneri , the author threw in criticism of Kropotkin's militarism. Berneri wrote, “Kropotkin separated from anarchism in his stance as a war advocate” and stated that the Manifesto of the Sixteen “marks the height of the incoherence of war-advocate anarchists; [Kropotkin] also supported Kerensky and the continuation of the war in Russia . ”The anarchist academic Vernon Richards speculates that, without the wish of Freedom editor Thomas Keell (who himself was a decided opponent of the war), to give the war advocates a fair chance from the start, they would have been politically isolated much earlier.

Russia

The historian Paul Avrich describes the effects of the dispute over support for the war as a division with “devastating” effects on the anarchist movement in Russia. The Moscow anarchists split into two groups, with the greater part supporting Kropotkin. The smaller part responded by giving up Kropotkin's anarcho-communism and turning to anarcho-syndicalism . Even so, the anarchist movement in Russia continued to gain strength. In an article in the December 1916 issue of State and Revolution , Bolshevik leader Lenin accused Russian anarchists of following Kropotkin and Grave, calling them "anarcho-chauvinists". Other Bolsheviks made similar remarks, such as Joseph Stalin , who wrote in a letter to a communist leader, “I read Kropotkin's article recently - the old fool must have completely lost his mind.” Lenin's protégé Leon Trotsky led Kropotkin's support for the war and the manifesto as further evidence to expose anarchism:

“Kropotkin, the retired anarchist who had a soft spot for the Narodniki since his youth , used the war to deny everything he taught for nearly half a century. This opponent of the state supported the Entente , and when he denounced the dual power in Russia it was not in the name of anarchy, but in the name of the sole power of the bourgeoisie. "

Historian George Woodcock called these criticisms acceptable insofar as they aimed at Kropotkin's militarism. On the other hand, he found the criticism of the Russian anarchists unjustified and, in relation to the accusation that the Russian anarchists supported the view of Kropotkin and Grave, wrote Woodcock, “nothing like this happened; only about a hundred anarchists signed the various declarations in favor of war; the majority of anarchists in all countries held on to the anti-militarist position just as consistently as the Bolsheviks. "

Switzerland

An angry group of “internationalists” in Geneva , including Grossman-Roschtschin, Alexander Ge and Kropotkin's former follower K. Orgeiani, called the anarchist defenders of the war “anarcho-patriots”. They wrote that the only form of war acceptable to true anarchists would be social revolution, which overthrows the bourgeoisie and its repressive institutions. Jean Wintsch , the founder of the Ferrer School in Lausanne and editor of La libre fédération , stood in isolation in the anarchist movement in Switzerland after announcing his support for the manifesto.

Spain

The Spanish anarcho-syndicalists rejected the war on the basis of the belief that there was no war party on the side of the workers. They furiously distanced themselves from their previous idols (including Kropotkin, Malato and Grave) after discovering that they had written the manifesto. Some Galician and Asturian anarchists disagreed and were denounced by the majority of Catalan anarchists who ultimately prevailed in the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo .

literature

- Paul Avrich : The Russian Anarchists . AK Press , Stirling 2006, ISBN 1904859488

- Camillo Berneri: Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas . Freedom Press , London 1943.

- John Crump: Hatta Shūzō and Pure Anarchism in Interwar Japan . Macmillan, 1993, ISBN 0312106319

- Emma Goldman : Living Life . Three volumes, Karin Kramer Verlag , Berlin 2002.

- Daniel Guérin : Ni Dieu ni Maître. Anthologie de L'anarchisme . 4 volumes, Maspero, Paris 1976, ISBN 2-7071-0390-X

- Jean Maitron: Le mouvement anarchiste en France . Paris 1975.

- Gerald Meaker: The Revolutionary Left in Spain, 1914-1923 . Stanford University Press, Stanford 1974, ISBN 0804708452

- Vernon Richards: Errico Malatesta: His Life & Ideas . Freedom Press, London 1965.

- Alfred Rosmer : Lenin's Moscow . Bookmarks, London 1987, ISBN 0906224373

- Alexandre Skirda: Facing the enemy. A history of anarchist organization from Proudhon to May 1968 . AK Press / Kate Sharpley Library , Edinburgh / Oakland [Calif.] 2002, ISBN 1902593197

- Alice Wexler: Emma Goldman: An Intimate Life . Pantheon Books, New York 1984, ISBN 0-394-52975-8

- George Woodcock: Peter Kropotkin: From Prince to Rebel . Black Rose Books, 1990, ISBN 0921689608

- George Woodcock, Ivan Avakumovic: The Anarchist Prince. A Biographical Study of Peter Kropotkin . TV Boardman, 1970.

Web links

- The text of the Manifesto of the Sixteen and the replies ( Memento of January 21, 2001 on the Internet Archive ) (fr.)

- Information on the Manifesto of the Sixteen ( Memento of June 4, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) in the Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia (eng.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 374.

- ↑ Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 379.

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin : A Letter to Steffen . In: Freedom . October 1914. Retrieved November 8, 2008.

- ↑ Michaël Confino: Anarchisme et internationalisme. Autour du Manifeste des Seize Correspondance inédite de Pierre Kropotkine et de Marie Goldsmith, janvier-mars 1916 Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétique . 22, No. 2-3, 1981. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ^ Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 382

- ↑ a b c d Richards, Errico Malatesta , pp. 219-222.

- ↑ Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 381.

- ↑ Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 383.

- ↑ a b Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 385.

- ↑ Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 383 f

- ↑ a b c d e f Woodcock, Peter Kropotkin , p. 384.

- ^ Maitron, Jean: Le mouvement anarchiste en France , p. 15.

- ↑ a b c d e f Avrich, Paul: The Russian Anarchists , pp. 116-119.

- ↑ a b Skirda, Alexandre: Facing the Enemy , p. 109.

- ^ Guérin, Daniel: No Gods, No Masters , p. 390.

- ^ Crump, John: Hatta Shūzō , p. 248.

- ^ Maitron, Jean: Le mouvement anarchiste en France. , P. 21.

- ^ Woodcock: Peter Kropotkin , pp. 384, 385.

- ↑ Nettlau, Max : Errico Malatesta. The life of an anarchist . Publishing house Der Syndikalist , Berlin 1922.

- ^ Rosmer, Alfred: Lenin's Moscow , p. 119.

- ^ Woodcock, George: The Anarchist Prince , p. 385.

- ^ Wexler, Alice: Emma Goldman: An Intimate Life , pp. 235-244.

- ^ Goldman, Emma: Living My Life , pp. 654-656.

- ^ Woodcock, George: Peter Kropotkin , p. 387.

- ^ Berneri, Camillo: Peter Kropotkin: His Federalist Ideas , p. 16.

- ↑ a b c Woodcock, George: Peter Kropotkin , p. 380.

- ↑ Ghe, Alexandre: Lettre ouverte à P. Kropotkine . Chadwyck-Healey Inc., Alexandria (Virginia) 1987.

- ^ IISG : Jean Wintsch Papers (last visited on December 6, 2008)

- ^ Meaker, Gerald: The Revolutionary Left in Spain , p. 28.