Matthew Murray (engineer)

Matthew Murray (1765 - February 20, 1826) was an English engineer and manufacturer of steam engines and machine tools . He designed the first commercially available steam locomotive , the Salamanca, in 1812. He also designed textile machines .

Early years

Little is known about Matthew Murray's early years. He was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1765. He left school at the age of fourteen and then trained as a blacksmith or tinsmith . In 1885 he finished his apprenticeship and married Mary Thompson (1764-1836) from Whickham , County Durham . The following year he moved to Stockton-on-Tees (Stockton) and began as a millwright working in the flat mill by John Kendrew , a mill in Darlington , the lines produced. It was there that machine production of linen was invented.

Murray and his wife Murray had three daughters and a son, also named Matthew.

Leeds

In 1789 Murray moved with his family to Leeds because the flax mill in Darlington was in trade deficit. In Leeds, Murray worked for the industrialist John Marshall , who was to become a well-known flax producer. Marschall had rented a small mill from Adel near Leeds to produce flax there, but also to recreate an existing flax spinning machine with the help of Murray. It took Murray several tries to construct a satisfactory machine. In early models, the flax fibers broke during the manufacturing process. The new machine enabled Marshall to build a new mill at Holbeck in 1791, for which Murray was responsible. The entire operation also included some of Murray's flax spinning machines, which he patented in 1790. In 1793 he received a patent for the construction of instruments and machines for spinning fibrous materials. His patent contained a carding machine and a new spinning machine with which flax was spun wet. This new technology revolutionized the flax trade. Murray maintained the machines and made some improvements. Apparently he was earning Marshall's trust, because at the time Murray was likely the mill's technical manager.

Fenton, Murray and Wood

The industry in Greater Leeds was developing rapidly and it soon became apparent that this was an excellent opportunity for engineers and mill builders to start up businesses. In 1795, Murray went into partnership with David Wood (1761-1820) and built a factory in Mill Green, near Holbeck . There were several mills in the surrounding area that were supplied with machines by the new company. The company grew rapidly, so in 1797 she moved to Water Lane, also at Holbeck. Two new partners were accepted there: James Fenton, who was formerly Marshall's partner, and William Lister, a mill builder from Bramley, a town near Leeds. The company became known as Fenton, Murray and Wood . Murray was the inventor and in charge of orders, Wood ran the day-to-day running of the factory, and Fenton was the accountant.

Construction of steam engines

The company continued to supply the textile industry, but Murray began to think about improving steam engines . Above all, he wanted to make them simpler, lighter and smaller. He also wanted the steam engine to be a self-contained unit that could be assembled on site with predictable accuracy. Many of the steam engines that existed at the time suffered from incorrect assembly that was difficult to correct. James Pickard already had a patent for converting the reciprocating cylinder movement into a rotary movement by means of a crank and flywheel , so this was no longer an option for Murray. Murray solved the problem by designing a hypocycloid gearbox . Murray's variant consisted of a large internally toothed gear that was permanently mounted. Inside ran an externally toothed gear with half the diameter of the large wheel. The inner wheel was driven by the piston of the cylinder via a connecting rod. This converted the linear movement of the cylinder into a rotating movement of the small gear. The bearing of the small wheel was connected to a crank that led to the shaft of a flywheel. Murray's construction made it possible to make the steam engines smaller and lighter. However, after Pickard's patent expired, Murray turned to its solution.

In 1799, William Murdock , who worked for Boulton & Watt - James Watt's company - invented a new type of valve for steam engines that allowed steam to first press on the piston from above and then from below. Murray improved this valve by connecting the valves to an eccentric gearbox that was attached to the machine's shaft to open and close it.

Murray also patented an automatic smoke extraction flap for ovens, which regulated the smoke extraction depending on the pressure in the boiler. He also designed a funnel that automatically fed the fuel into the combustion chamber. He was the first to adopt the horizontal alignment of the piston in steam engines. Murray expected his employees to have a high level of craftsmanship and ability, which enabled the company to build very precise machines. He constructed a special planing machine that was used to process valves . Apparently this planer was set up in a separate room that was only accessible to a few employees.

The Murray hypocycloidal steam engine in the Birmingham Museum is the third oldest working steam engine in the world and the oldest with a hypocycloidal gearing.

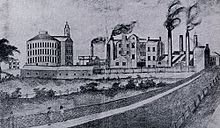

New factory

Because of the high quality steam engines, sales increased very quickly and a new assembly hall was acquired. Murray she designed herself and built a round, three-story building, as Round Foundry ( Round Foundry ) was known. At its center was a steam engine that powered all the machines in the building. Murray also built a house for himself in the area. The construction was groundbreaking, as every single room was heated by pipes through which steam was passed. Therefore, it became known as Steam Hall (in the vicinity steam room ).

Competition with Boulton and Watt

The success that Fenton, Murray & Wood enjoyed because of their high quality craftsmanship drew the attention of competitors Boulton & Watt. This sent the employees William Murdoch and Abraham Storey to Murray, ostensibly because of a courtesy visit, but in truth to spy on Murray's factory and its production methods. Murray foolishly welcomed them and showed them the entire factory. The two visitors informed their employer that Murray's castings and forgings were clearly superior to their own. Boulton & Watt made some effort to adopt Murray's production methods. There was also an attempt by Boulton & Watt to obtain additional information by bribing Murray's employees. Ultimately, James Watt jun. Land near Murray's factory to prevent them from further expanding the factory.

Boulton & Watt successfully took action against two of Murray's patents. The 1801 patent for the improvement of an air pump and other innovations and the 1802 patent for a self-contained, compact machine with a novel valve. In both cases, Murray made the mistake of combining too many innovations in one patent, since the entire patent was invalid if only a part of the innovations represented a patent infringement.

Despite the activities of Boulton & Watt, Fenton, Murray & Wood became a serious competitor and received many orders.

Steam locomotives

In 1812 Murray's company supplied John Blenkinsop , manager of a coal mine in Middleton , near Leeds, with the first two-cylinder steam locomotive to Salamanca . It was also the first commercially successful steam locomotive.

The double cylinder was Murray's invention. He paid royalties to Richard Trevithick to use his patent for a high pressure steam system. Murray was able to further improve the design by using two cylinders, which made the drive run more smoothly.

Only light locomotives could run on the cast iron rails, otherwise the rails would break. The payload was therefore severely limited. John Blenkinsop received a patent for a cogwheel and the construction of a cogwheel train in 1811 . The gear in the locomotive was driven by connecting rods and engaged in racks that were located between the rails. Blenkinsops Bahn was thus the first rack railway and had a track width of 1,245 mm (4 feet 1 inch ).

Around 1819 the system was switched to malleable cast iron rails . The rack and pinion drive has therefore become superfluous, apart from applications in mountain railways. At that time, however, the rack railway made it possible to transport goods whose weight was at least 20 times the weight of the railway. The Salamanca was so successful that Murray built three more models. One of them became known as Lord Wellington , named after the contemporary British politician and general Lord Wellington , another was supposedly called Prince Regent ( Prince Regent ) and Marquis Wellington ( Duke of Wellington ). There are no contemporary sources for the last two names. The third locomotive was originally planned for Middleton, but at Blenkinsop's request it was sent to Kenton to another coal mine near Newcastle upon Tyne . There she was apparently referred to as Willington . It was seen there by George Stephenson , who used it as a model for his own Blücher locomotive . However, he did without the rack and pinion drive, making it less efficient.

Marine propulsion

In 1811 the Murrays company built a Trevithick model of high pressure steam engine for John Wright, a Quaker from Great Yarmouth , Norfolk . The machine was installed in the paddle steamer l'Actif , which left Yarmouth. The ship was acquired by the government and used as a warship. Bucket wheels were attached which were driven by the new machine. The ship was renamed Experiment . The drive was very successful and was eventually transferred to another boat called The Courier .

In 1816, the US consul in Liverpool , Francis B. Ogden, received a two-cylinder ship propulsion system from Murray's company. Ogden had the design patented in America as his own idea. The construction was often copied and was used to power the Mississippi damper.

Innovations in textile machines

Murray made important improvements to machines for panting and spinning flax. Panting is the preparation of the flax for spinning. The flax fibers are split and straightened. For his hackle machine he received the gold medal of the Royal Society of Arts in 1809. At the time of the inventions, the trade in flax was just about to come to a standstill, as the spinners were no longer able to profitably produce yarn. Murray's machines resulted in cost reductions in the production process and improved product quality, so that the British linen trade had a solid foundation. The manufacture of textile machines became an important branch of the manufacturing industry in Leeds. They were produced in large quantities, both for domestic use and for export, which created numerous jobs for highly skilled craftsmen.

Hydraulic presses

In 1814, Murray received a patent for a hydraulic press for bracing cloth. In this press, the two halves of the tool moved towards each other at the same time, which was an improvement over Joseph Bramah's press . In 1825 Murray constructed a chain testing press for a Navy Board. She was 34 feet long and could muster a force of 1,000 tons. It was completed shortly before Murray's death.

death

Murray died on February 20, 1826 at the age of sixty. He was buried in the cemetery of St Matthew's Church in Holbeck. On his grave is a cast iron obelisk made by the Round Foundry. His company existed until 1843. Several well-known engineers were trained there, including Benjamin Hick , Charles Todd , David Joy and Richard Peacock .

Because of his good construction and craftsmanship, several of his mills ran for over 80 years, one of which was used in the repair shop of King's Cross Station for over a century.

Murray's only son Matthew (1793-1835) began an apprenticeship in the Round Foundry and emigrated to Russia. There he started a trade in Moscow , where he died at the age of 42.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alex J. Warden: The Linen Trade: Ancient and Modern. (1864). Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, London 1967, pp. 690-692.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j L. TC Rolt: Great Engineers: G. Bell and Sons, London 1962.

- ^ John Farey: A treatise on the steam engine: historical, practical, and descriptive. Volume I, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, London 1827, p. 693.

- ↑ automuseums.info "Thinktank Birmingham Science Museum." Car museum. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ↑ a b Robert Havall (1814). "'The Collier', 1814". Science & Society Picture Library Prints. Science Museum / Science & Society Picture Library. ( spartacus-educational.com Retrieved July 13, 2016)

- ^ Samuel Smiles , Robert Stephenson : The Life of George Stephenson: Railway Engineer . 5th edition. J. Murray, 1858, p. 75 ( google.co.uk [accessed May 11, 2016]).

- ^ Matthew Murray. In: Grace's Guide. 2016, accessed May 11, 2016 .

- ↑ Mike Chrimes: Matthew Murray. In: AW Skempton et al. (Ed.): A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers. Vol 1, Thomas Telford, London 2002, ISBN 0-7277-2939-X , pp. 461-462.

Bibliography

- Mike Chrimes: Matthew Murray. In: AW Skempton et al. (Ed.): A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers. Vol 1, Thomas Telford, London 2002, ISBN 0-7277-2939-X , pp. 461-462.

- G. Cookson: Early Textile Engineers in Leeds, 1780-1850. In: Publications of Thoresby Society. Volume 4, 1994, pp. 40-61.

- Walter English: The Textile Industry: An Account of the Early Inventions of Spinning, Weaving, and Knitting Machines. (= Industrial Archeology. Volume 4). Longmans, Harlow 1969, OCLC 499966626 , pp. 157-160.

- Ernest Kilburn Scott: Matthew Murray: Pioneer Engineer. Records from 1765 to 1826. E. Jowett, Leeds 1928, OCLC 1686282 .

- Joseph Wickham Roe: English and American Tool Builders. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut 1916, LCCN 16011753. (Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York / London 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and Lindsay Publications, Bradley, Illinois, ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7 .)

- LTC Rolt: Great Engineers. G. Bell and Sons, London 1962, OCLC 460171705 .

- Samuel Smiles: Industrial Biography. (1861). John Murray, London 1901.

- Alex J. Warden: The Linen Trade: Ancient and Modern. (1864). Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, London 1967, OCLC 9078821 , pp. 690-692.

Web links

- Holbeck Urban Village, Leeds Illustrated page on Murray and his work

- The Guardian The Northerner: Article on Murray and Leeds

- Leeds Engine Builders England's Biggest Locomotive Building City

- Spartacus Educational Matthew Murray

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Murray, Matthew |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English engineer and manufacturer of steam engines and machine tools |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1765 |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 20, 1826 |