Maulid an-Nabī

Maulid an-Nabī ( Arabic مولد النبي 'Prophet's Birthday') is an Islamic festival in honor of the Prophet Mohammed . It is celebrated on the 12th day of the month of Rabīʿ al-auwal on the Islamic calendar . The day is a national holiday in several Islamic countries, including Indonesia and Malaysia . In Turkey the day is called Mevlid or Mevlüt , in Indonesia this festival day is also called maulud or mulud (from Arabic maulūd ). Due to the fact that the 12th Rabīʿ al-auwal as the birthday of the Prophet is not certain and that the first generations of Muslims did not celebrate this day with a ceremony, there is also criticism of the Maulid celebrations from various Sunni currents.

Origin and spread of the festival

In contrast to the festival of the sacrifice and the festival of the breaking of the fast , the birth festival of the prophet came into being in post-prophetic times. Greater interest in the birth and childhood of Muhammad first arose in the early Abbasid period . It was Chaizurān, the mother of Hārūn ar-Raschīd (d. 789), who turned the house in which Mohammed was born into a place of prayer. Celebrations of the prophet's birthday were first introduced in the 11th century at the court of the Shiite Fatimids and were a means of emphasizing the dynasty's descent from the prophet. The caliph played a central role in the celebrations; public sermons and readings of the Koran took place. According to a report by the historian Ibn Tuwair, a preacher delivered a sermon at the end of which he stated: “And this is the day he was born to fulfill his mission, with which God established the fellowship of Islam ( millat al-Islām ) has blessed. "

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the custom was adopted by various Sunni rulers. The first Sunni ruler to officially celebrate the festival was the Zengide Nūr ad-Dīn (ruled 1146–1176). In the 1170s, ʿUmar al-Mallāʾ, a private citizen in Mosul , who was acquainted with Nūr ad-Dīn, began to organize Maulid celebrations. About twenty years later the festival was also celebrated in Mecca , as can be seen in Ibn Jubair's travelogue . The splendid Maulid celebrations, which the Begteginid ruler Muzaffar ad-Dīn Gökböri had held in his residence in Erbil at the beginning of the 13th century, caused a particular sensation . They were accompanied by Sufi samāʿ concerts and banquets.

A Maghrebian scholar, Abū l-ʿAbbās al-ʿAzafī, wrote a pamphlet during this time in which he praised the maulid festival as a means of ideologically defending Christianity and strengthening the unity of Muslims. Celebrated for the first time in Ceuta in 1236 , this festival subsequently spread across the entire Maghreb. The maulid festival was particularly popular among the Merinids . The Merinid ruler Abū Inān Fāris regularly organized large banquets throughout the country on the night of the Prophet's birthday .

In Java , the Prophet's birth festival has been documented since the 16th century. The Javanese royal courts celebrated it with great pomp, even at a time when Islam was only establishing itself there.

procedure

Feast

Maulid celebrations almost always include lavish dining, to which the poor are usually invited. According to a contemporary witness, quoted by the Syrian scholar Sibt ibn al-Jschauzī (st. 1257), 5,000 roasted sheep, 10,000 chickens, 100,000 bowls of zabdīya and 30,000 platters were brought along at a maulid banquet organized by Muzaffar ad-Dīn Gökböri Sweets handed. A banquet that the Mamluken Sultan az-Zahir Barquq gave in Cairo in 1383 was similarly lavish . The expenses for food, drinks, incense, robes of honor and reciteers of the Koran amounted to 10,000 gold mithqāl. One of the basic ideas behind these banquets was that they wanted to thank God in this way for creating the prophet Mohammed and sending him to the people. Scholars like ʿAlī al-Qārī (d. 1606), who themselves did not have sufficient financial means to host a maulid banquet, wrote Maulid writings in order to thank God for the favor they had received. In Java, the feasts on the occasion of the prophet's birthday are called muludan .

Lecture of stories of the prophets

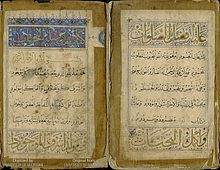

Another element of the Maulid celebrations is the recitation of stories that tell of Muhammad's birth and life. One of the best-known of these stories is the work ʿIqd al-ǧawāhir ("Jewel Collar ") by Jafar al-Barzandschī (1690–1765), which is very popular in Egypt, Nigeria, East Africa and South and Southeast Asia. There are two versions of the text ʿIqd al-ǧawāhir , also known only by the name Maulid al-Barzanjī , one in prose and the other in verse. There are also many comments and interlinear translations . In total, the work is divided into 19 sections. The first ten sections deal with the miraculous apparitions at Muhammad's birth and events from his youth, the 12th section deals with his first revelations, the 13th deals with his first followers, the 14th describes the ascension of Muhammad , and the 17th his Characteristic qualities and his physical beauty are highlighted, the final 19th section contains hymns of praise and formulas. In Indonesia the work was performed choreographically on various stages in the 1970s, and today numerous films of recitations of Maulid al-Barzanji can be found on the Internet.

In the Swahili region, the maulidi text of the hadramitic scholar ʿAlī ibn Muhammad al-Habschī (1843–1915) is also recited. He was introduced into Swahili society by Habīb Sālih from Lamu at the end of the 19th century . In Turkey, the Maulid celebrations are based on the Turkish Masnawī Vesīletü n-neǧāt ("means of salvation") by Süleymān Çelebi (d. 1422).

Overall, the recitation of the maulid texts is said to have a beneficial effect . An integral part of these recitation rituals is the joint uttering of blessings for the prophet at certain points in the text. As soon as the birth of Muhammad was mentioned in the recitation of these texts, it was customary to stand up. This standing up ( qiyām ) at the mention of Muhammad's birth was even made mandatory in the 16th century in the area of the Ottoman Empire . The Ottoman legal scholar Ebussuud Efendi (d. 1574) ruled in a legal opinion that those who did not get up on the occasion were suspected of being unbelievers.

Speeches

On Maulid Day, official speeches are often given in Islamic countries, in which the role of Islam for national and international development is emphasized. For example, on Maulid Day in 1962 (August 11), Habib Bourguiba gave a speech in the main mosque of Qairawān about the fact that Islam is not an obstacle to progress. The Indonesian President Suharto , who gave frequent Maulid speeches in the 1970s, emphasized that the serious adherence to religious beliefs is a prerequisite for the spiritual maturation of a developing country like Indonesia. And in 2006, on Maulid Day , Muammar al-Gaddafi gave a speech in Timbuktu in which he presented himself as “the leader of the Global Islamic People's Command ” ( qāʾid al-Qiyāda aš-Šaʿbīya al-Islāmīya al-ʿĀlamīya ). Speeches are also usually given in schools and universities and at the headquarters of Islamic organizations.

Parades and fairs

As the Hanafi scholar Ibn Diyā 'al-Makkī (d. 1450), who worked in Mecca as Qādī and Muhtasib , reports in a treatise, a festive procession took place in Mecca on the night of the prophet's birthday during his time. For this purpose, the carpet- spreaders ( farrāšūn ) of the Holy Mosque gathered with candles and lanterns in the mosque courtyard and in this way led the Khatīb to the birth house of the Prophet. Men, women and children took part in the parade.

In the city of Yogyakarta on Java, Maulid Day is preceded by a whole week of festivities with parades, music performances and lectures of the stories of the prophets. During this time there is a fair on the northern forecourt of the Kraton called the Sekaten . On the first day of the festival week , two gamelan orchestras, considered sacred, are brought from the Kraton to the outer courtyard of the Great Mosque and play there for the entire week. On the eve of Maulid Day, they are ceremoniously carried back to the Sultan's Palace at 11 p.m. and may then no longer be played until the next week of secaten.

The so-called Garebeg-Maulud rituals take place in Yogyakarta and Surakarta on the prophet's birthday. The so-called "food mountains" ( gunungan ) are solemnly transferred in a procession from the courtyard of the palace to the courtyard of the Great Mosque. Numerous gun salutes are fired during the défilé. As soon as the mountains of food have reached their destination, the crowd tries to get hold of parts of the food, as this, like the gamelan orchestra, is considered to be a bearer of blessing power . The official part of the festival ends with a wayang performance in the evening .

Modern Maulid criticism

Since the 18th century there have been several currents of Sunni Islam that deny the admissibility of the Maulid celebrations and reject them as a violation of the principle that God alone is due. This includes in particular the Wahhabis . When they conquered Mecca in 1803 , they banned the Maulid meetings there.

In addition, from the late 19th century onwards, the custom of standing up at the Maulid met with criticism from an increasing number of scholars, and separate texts were written on this question. In Southeast Asia, the rejection of the Maulid rising ( berdiri mawlid ) was a hallmark of the reform-oriented Kaum Muda , who were based on the Salafi ideas of Muhammad Abduh and Raschīd Ridā .

In Saudi Arabia, where the Wahhabi doctrine is supported by the state, the Maulid celebrations were declared inadmissible several times in legal opinions in the 20th century. In particular, the Saudi Grand Mufti ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn Bāz (d. 1910–1999) spoke out in favor of a complete ban on Maulid celebrations. Under the impression of a text by him, which was translated into Swahili , debates arose in Kenya at the beginning of the 21st century about the permissibility of this festival. Abdilahi Nassir, a popular Swahili scholar who converted to the Twelve Shia during the 1980s , defended the Maulid celebrations against its critics in a series of lectures in 2002.

Also in the Ahl-i Hadīth and Deobandi , the Maulid celebrations are regarded as an inadmissible innovation ( Bidʿa ). The opponents of Maulid an-Nabi argue, among other things, that it is an imitation of the Christian Christmas festival. Other Muslims say that Mohammed himself and his companions had already celebrated his birthday in a special way, but with fasting , not with celebration.

Other Maulid festivals

In Egypt, in addition to the birthday of the prophet, the birthdays of various Islamic saints are also celebrated, for example al-Husain ibn ʿAlī and Ahmad al-Badawi . These festivals are also known as Maulid (or in the Egyptian colloquial language Mulid ).

literature

Arabic Maulid texts

- ʿAlī Ibn-Sulṭān Muḥammad al-Qārī al-Harawī: Al-Maurid ar-rawī fī maulid an-nabī . Ed. Mabrūk Ismāʿīl Mabrūk. Cairo: Maktabat al-Qurʾān 1992.

- Maulid al-Barzanǧī . Ed. Bassām Muḥammad Bārūd. Abu Dhabi 2008. Text edition with instructions for the recitation, digitized

Secondary literature

- Abdallah Chanfi Ahmed: La passion pour le Prophète aux Comores et en Afrique de l'Est ou l'épopée du maulid al-Barzandji . In: Islam et sociétés au sud du Sahara 13 (1999) 65–89.

- Herman Beck: Islamic purity at odds with Javanese identity: the Muhammadiyah and the celebration of the Garebeg Maulud ritual in Yogyakarta . In: Jan Platvoet, Karel van der Toorn (eds.): Pluralism and Identity: Studies in Ritual Behavior . Leiden: Brill 1995. pp. 261-284.

- Irmgard Engelke: Sülejmān Tschelebi's praise poem on the birth of the Prophet (Mewlid-I-Šerīf) . Halle (Saale): Karras, Kröber & Nietschmann 1926.

- H. Fuchs, F. de Jong: Art. "Mawlid or Mawlūd. 1. Typology of the mawlid and its diffusion through the Islamic world" in The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition Vol. VI, pp. 895a-897b.

- Denis Gril: La commémoration de la naissance du Prophète (mawlid al ‑ nabî) in G. Dorival and J.-P. Boyer (eds.): Nativité et le temps de Noël. Aix ‑ en-Provence: Publications de l'Université de Provence , 2003, pp. 189--202.

- Norbert Hofmann: The Islamic festival calendar in Java and Sumatra with special consideration of the fasting month and fasting break festival in Jakarta and Medan . Bad Honnef: Bock + Herchen 1978. pp. 67-89. Available online here .

- Nico Kaptein: Materials for the History of the Prophet Muhammad's Birthday Celebration in Mecca . In: Der Islam 69 (1992) 193-246

- NJG Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. Early History in the Central Muslim Lands and Development in the Muslim West until the 10th / 16th Century. Suffering u. a .: Brill 1993.

- Nico Kaptein: The Berdiri Mawlid issue among Indonesian muslims in the period from circa 1875 to 1930 . In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 149 (1993) 124–153. Available online here .

- Marion Holmes Katz: The birth of the prophet Muhammad: devotional piety in Sunni Islam. London 2009.

- Kai Kresse: “Debating maulidi : Ambiguities and Transformations of Muslim Identity along the Kenyan Swahili Coast” in Roman Loimeier, Rüdiger Sesemann (eds.): The Global Worlds of the Swahili. Interfaces of Islam, Identity and Space in 19th and 20th-Century East Africa. Lit, Münster, 2006. pp. 209-228.

- Gustav Neuhaus: Kitabu Mauludi, book of the birth of Muhammad’s . In: Communications from the Seminar for Oriental Languages 38 (1935) 145–201.

- Hanni Nuotio: "The Dance that is not Danced, the Song that is not Sung: Zanzibari Women in the maulidi Ritual" in Roman Loimeier, Rüdiger Sesemann (eds.): The Global Worlds of the Swahili. Interfaces of Islam, Identity and Space in 19th and 20th-Century East Africa. Lit, Münster, 2006. pp. 187-208.

- Aviva Schussmann: The legitimacy and nature of mawlid an-nabī (analysis of a fatwā) . In: Islamic Law and Society 5 (1998) 214-233.

- Samuli Schielke: Mawlids & Modernists. Dangers of Fun. ISIM Review 17, Leiden 2006, pp. 6-7 (online) .

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Hofmann: The Islamic festival calendar in Java and Sumatra . 1978, p. 67.

- ↑ See Fuchs, de Jong: "Mawlid or Mawlūd" in EI² Vol. VI, p. 895a.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, pp. 20-28.

- ↑ Quoted from Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, p. 15.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, pp. 31-34.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, pp. 34-38.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, pp. 38-40.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, pp. 40f.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, pp. 77-89.

- ↑ See Kaptein: Muḥammad's Birthday Festival. 1993, p. 107.

- ↑ See Hofmann 31.

- ↑ See Hofmann 70.

- ↑ Cf. Katz: The birth of the prophet Muhammad . 2009, pp. 63-67.

- ↑ Cf. Katz: The birth of the prophet Muhammad . 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ See Hofmann 69.

- ↑ See Ahmed, Neuhaus and Hofmann: The Islamic Festival Calendar in Java and Sumatra . 1978, pp. 80-82.

- ^ See the summaries in Hofmann 82 and Abdallah Chanfi Ahmed: Ngoma et mission islamique ( Daʿwa ) aux Comores et en Afrique orientale. Une approche anthropologique . Paris 2002. pp. 23-33.

- ↑ See Hofmann 83–86.

- ↑ See e.g. B. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ws9Bc2VB8PI

- ↑ See Kresse: "Debating maulidi ". 2006, pp. 210, 217f, 226.

- ↑ See Engelke: Sülejmān Tschelebi's praise poem . 1926.

- ↑ See Katz 86–92.

- ↑ Cf. Katz 128-139.

- ↑ The text of the speech with the title al-Islām laisa bi-ʿarqala fī waǧh ar-ruqīy was published on August 15, 1962 by the Tunisian "State Secretariat for Cultural Affairs and News" ( Kitābat ad-Daula li'š-Šuʾūn at-Taqāfīya wa'l-Aḫbār ) published.

- ↑ See Hofmann 69.

- ↑ See The speech of the leader of World Islamic People's Leadership (WIPL): on the occasion of the prophet's birthday, held in Timbuktu . SL World Islamic Call Center 2006.

- ↑ See Hofmann 70.

- ↑ Abū l-Baqāʾ Ibn Ḍiyāʾ al-Makkī (d. 1450): Muḫtaṣar Tanzīh al-Masǧid al-Ḥarām ʿan bidaʿ al-ǧahala al-ʿawāmm . Ed. Niẓām Muḥammad Ṣāliḥ Yaʿqūbī. Dār al-Bašāʾir al-Islāmīya, Beirut, 1999. pp. 17f. Digitized

- ↑ See Hofmann 72f and Beck.

- ↑ See Hofmann 73 and Beck 266f.

- ↑ Cf. Katz: The birth of the prophet Muhammad . 2009, p. 171.

- ↑ Cf. Katz: The birth of the prophet Muhammad . 2009, pp. 134-139.

- ↑ See Kaptein 1993.

- ↑ Cf. Katz: The birth of the prophet Muhammad . 2009, p. 186.

- ↑ See Kresse: "Debating maulidi ". 2006, p. 220.

- ↑ See Kresse: "Debating maulidi ". 2006, p. 223.

- ↑ See Rudolf Kriss u. Hubert Kriss-Heinrich: Popular belief in the area of Islam , Vol. 1: Pilgrimage and veneration of saints . Wiesbaden 1960. pp. 55-57.