Ostracods

| Mussel crabs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Shellfish ( Ostracoda ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Ostracoda | ||||||||||||

| Latreille , 1802 |

The mussel crabs or ostracods ( Ostracoda ) are small crustaceans , their size varies between 0.2 and 30 mm at most, most are between 0.5 and 2 mm in size. They colonize all aquatic habitats from the sea to the brackish water , the rivers , the lakes , the springs to small puddles in the meadow, also the groundwater and with some species, e.g. B. Microdarwinula zimmeri , even semi-aquatic habitats. Only in the waters of the raised bogs are they completely absent due to the lack of lime and the low pH value . Only a few species are adapted to neutral, but lime-free water, e.g. B. Cryptocandona reducta , after death the shells dissolve very quickly.

The mussel crabs are arthropods (Arthropoda) from the sub-tribe of the crustaceans (Crustacea), class Ostracoda (from ancient Greek ostrakon " pottery shard "). The crabs owe their German name "mussel crabs" to the skin duplicates that are reminiscent of mussel shells and protect the soft body. These are median-symmetrical folds of the head, the outer and (less often) inner chitin lamella of which are mineralized by calcium carbonate and form the carapace from two shell halves, making them look like small shells .

There are currently an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 species of ostracods on earth, most of them marine and only about 2,000 in freshwater and brackish water . They have been known as fossils since the Old Paleozoic . A total of about 65,000 recent and fossil species have been described so far, of which only about 33,000 are valid due to synonymy .

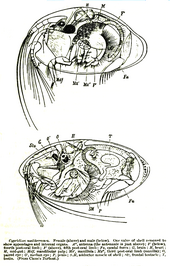

Soft body construction

The complex structure of the soft body is the basis of the taxonomic structure. The laterally flattened soft body is not segmented, a separation is indicated only by a furrow between the head ( cephalon ) and trunk (thorax) from the back and from the sides. In the order Podocopida there are four of the seven pairs of limbs on the head: Antennula (A1) and antenna (A2) in front of the mouth opening and mandible (Md) and maxilla (Mx1) behind the mouth opening. The interaction of A1 and A2 is used to control movement and the presence and formation of so-called swim bristles on the A2 are crucial for swimming ability. The thorax carries at least three pairs of legs, the so-called thoracopods (T1 to T3) with a special functionality. The unpaired so-called furka forms the end of the body. Details on the fine structure of the Podocopida, including the fine structure of the males, which are not found in all species, can be found in W. Klie.

Way of life

Most species of shellfish move crawling or sliding across the bottom of the water. Some of these benthic species can swim short distances. They feed on the sinking dead animal and vegetable remains, rummaging through the mud, they ensure the mineralization of the detritus . As a result, they play an important role in the water ecosystem. Some of the ostracods that live in freshwater have a highly specialized diet, for example Notodromas monacha grazes the skin on the surface of the water. Permanently active swimming, i.e. species belonging to the nekton , z. B. Cypridopsis vidua feed mainly on microalgae. Some are predatory, including the genus Gigantocypris , whose representatives catch very small juvenile fish and arrowworms. With a size of up to 30 millimeters, these deep-sea (bathypelagic) ostracods are the largest mussel crabs. Even cannibalism is obviously widespread, because dead fellows are like eating the carcasses of other animals. It was observed that freshly killed specimens of Cypris pubera immediately attracted large numbers of conspecifics. Ostracodes are said to live as commensals on other crabs. B. Species of the genus Entocythere on the gills and limbs of the genus Cambarus (class of crayfish ) occurring in America . Also on amphipods some species of ostracods can be found.

The lifespan of the shellfish is only a few weeks for some species. One of the species with the longest lifespan is Philomedes globosus , this marine species is only sexually mature from two years and can live up to four years. The mussel crabs that live in the sea are predominantly cosmopolitans and not infrequently also ubiquists . However, many of the ostracodes that live in freshwater are highly specialized in their ecological requirements. In Central Europe, for example, the so-called “spring forms” develop within a few weeks from the eggs to the larval stages up to early summer and die after the eggs have been laid as the waters dry out. Others are adapted to the climatic conditions of the arctic regions, e.g. B. Fabaeformiscandona harmsworthi . Their detection in cold-age sediments in Central Europe is an important indicator for the reconstruction of climatic changes, see below.

Reproduction

The mussel crabs are always separate sexes. The males of many species, especially those living in freshwater, are not known; they reproduce through parthenogenesis . This type of reproduction has the advantage that a single egg, which can be transported over great distances by bird migration, can develop into a new population in a biotope preferred by the species . This is the only way to explain the occurrence of the species Ilyocypris getica in an anthropogenic body of water. The eggs are laid freely in the water individually or in small packages. They are extremely resistant, protected by a double cover, they survive the complete drying out and freezing of the living water in many species. However, some species, for example Darwinula stevensoni , are viviparous, they do not survive freezing through the water. Development begins with a nauplius larva that already has a two-lobed shell . This already has small mandibles . This is followed by stages with a maximum of eight moults . Only in the adult animal that no longer sheds its skin are all the characteristics of the soft body and shells fully developed.

Importance to humans

As already mentioned above, the ostracods have recently played a major role in the destruction of dead organic substances in the waters, e.g. B. the leaves of deciduous trees entered in autumn.

Due to the good preservation of the shells in calcareous sediments, their small size and abundant occurrences, as well as their evolutionary short life, marine ostracode species have long been used as key fossils in the prospecting of petroleum .

The ostracodes bound to the fresh water are well suited for the investigation of questions in the Quaternary geology , both for the reconstruction of the environment during archaeological excavations, as well as for the investigation of climate changes ( palaeoclimatology ), e.g. B. in the Holocene Recent studies in central Germany have shown that the freshwater ostracodes are also suitable for the stratigraphic classification of the Quaternary , both to differentiate between the interglacials and the cold ages .

literature

- GW Müller: The ostracodes of the Gulf of Naples and the adjacent sea sections. (= Fauna and flora of the Gulf of Naples. Volume 21). Berlin 1894. (PDF)

- GW Müller: Germany's freshwater ostracods. In: Zoologica . Issue 30, Stuttgart 1900, pp. 1–112, 21 plates.

- GW Müller: Ostracoda. In: FE Schulze: The animal kingdom. 31. Delivery, Berlin 1912. (PDF)

- W. Klie: Ostracoda, mussel crabs. - In: F. DAHL (ed.): The animal world of Germany and the adjacent parts of the sea according to their characteristics and their way of life. Volume 34 (3), Jena 1938, pp. 1-320.

- G. Hartmann: Ostracoda. In: H.-E. Gruner (Ed.): Dr. HG Bronn's Classes and Orders of the Animal Kingdom. Volume 5: Arthropoda. Dept. 1: Crustacea. Book 2, part 4, volume 1, Geest & Portig, Leipzig 1966, pp. 1–216, fig. 1–121.

- KJ Müller: Hesslandona unisulcata. sp. nov. with phosphatised appendages from Upper Cambrian 'Orsten' of Sweden. In: RHE Robinson, LM Sheppard (eds.): Fossil and Recent Ostracods. Ellis Horwood, Chichester 1982, pp. 276-304.

- On the Upper Bathonium (Middle Jura) in the Hildesheim area, northwest Germany - mega- and micropalaeontology, biostratigraphy. In: Geological Yearbook. Series A, issue 121. Hannover 1990, pp. 73-118.

- HI Griffiths: European Quaternary Freshwater Ostracoda: a Biostratigraphic and Palaeobiogeographic Primer. In: Scopolia. Volume 34, Ljubljana 1995, pp. 1–168.

- C. Meisch : Freshwater Ostracoda of Western and Central Europe. In: Freshwater fauna of Central Europe. 8/3. Spectrum Academic Publishing House, 2000, ISBN 3-8274-1001-0 . (In English. The following countries are taken into account: Ireland, Great Britain, northern half of France, Benelux countries, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia)

- LE Park, RD Ricketts: Evolutionary history of the Ostracoda and the origin of nonmarine faunas. In: LE Park, AJ Smith (Ed.): Bridging the Gap. Trends in the Ostracode Biological and Geological Sciences. In: The Paleontological Society Papers. Volume 9, Tulsa / Okla 2003. ISSN 1089-3326

- R. Fuhrmann: Atlas of Quaternary and recent ostracodes of Central Germany. In: Altenburger scientific research. Issue 15, Altenburg 2012, pp. 1–320, 142 plates. [12] .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Microdarwinula zimmeri [1]

- ↑ Cryptocandona reducta [2]

- ^ The class of the Ostracoda. In: Fauna Europeae Database. European Commission, accessed on February 24, 2010 .

- ↑ DJ Horne, A. Cohen, K. Martens: Taxonomy, Morphology and Biology of Quaternary and Living Ostracoda. In: JA Holmes, AR Chivas (Ed.): The Ostracoda: Applications in Quaternary Research. (= Geophysical Monograph Series. 131). American Geophysical Union, Washington / DC 2002, ISBN 0-87590-990-6 , pp. 5-36.

- ^ Walter Klie [3]

- ^ W. Klie: Ostracoda, mussel crabs. - In: F. DAHL (ed.): The animal world of Germany and the adjacent parts of the sea according to their characteristics and their way of life. Volume 34 (3), Jena 1938, pp. 1-320

- ↑ Notodromas monacha [4]

- ↑ Cypridopsis vidua [5]

- ↑ Cypris pubera [6]

- ↑ Fabaeformiscandona harmsworthi [7]

- ^ JW Neale: The freshwater Ostracod 'Candona harmsworthi' Scott, from Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya. In: JW Neale (Ed.): The taxonomy, morphology and ecology of Recent Ostracoda. Edinburgh 1969, pp. 222-246

- ↑ Ilyocypris getica [8]

- ^ C. Meisch, R. Fuhrmann, K. Wouters: Ilyocypris getica Masi, 1906 (Crustacea, Ostracoda): Taxonomy, Ecology, Life History, Distribution, Fossil Occurence and First Record for Germany. In: Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle de Luxembourg. Volume 23, Luxembourg 1996, pp. 3–28 [9]

- ↑ Darwinula stevensoni [10]

- ↑ P. Frenzel, R. Matzke-Karasz, FA Viehberg: Shell crabs as witnesses of the past. In: Biology in Our Time. 36 (2), 2006, pp. 102-108, ISSN 0045-205X

- ↑ R. Fuhrmann: The ostracod and mollusc fauna of the alluvial clay profile Zeitz (Burgenland district) and their statement on the climate and land use in the younger Holocene of Central Germany. In: Mauritiana. Altenburg 2008, Volume 20 (2), pp. 253-281. (PDF)

- ↑ R. Fuhrmann: The ostracod fauna of the interglacial basins of Neumark-Nord (Geiseltal, Saxony-Anhalt) and their statement on the stratigraphic position. In: Mauritiana. Altenburg 2017, Volume 32, pp. 40-105 (PDF)

- ↑ R. Fuhrmann: The ostracod fauna of the Vistula Cold Age layer sequence of the Schadeleben open-cast lignite mine (outskirts of the Nachterstedt open-cast mine) in the former Lake Aschersleben (Saxony-Anhalt). In: Mauritiana. Altenburg 2012, Volume 24, pp. 29–50 (PDF)

- ^ R. Fuhrmann: The ostracod fauna of the Weichselpleniglacial loess in western and central Saxony . [11]