Pest management

As Plagge fertilization (also Plagge economy or Esch culture ) refers to a no longer employed form of management of underperforming soils, especially in Northern Germany and adjacent areas since at least the Iron Age to the Industrial Revolution was widespread. In the process, heather and forest soils were removed ( plagues ) and used as litter in the stables. The litter, enriched with animal excrement, was spread out again and used as fertilizer on the fields.

Reasons for pest fertilization

Before the introduction of mineral trade fertilizer suffered farming on the sandy soils of the North German Geest and related fields from a lack of fertilizer materials. They managed by applying heather or forest soil that had been removed elsewhere onto the arable land, the so-called Eschfeldern ( Plaggenesch ).

Plague fertilization in the narrower sense began very suddenly in most areas in the middle of the 10th century , probably under pressure from strong landlords . Before the 10th century, a rotation economy with spring barley , legumes and flax was probably grown, which, in contrast to the "eternal rye cultivation" ( single field farming ), had enabled better regeneration of the fields and thus made (pest) fertilization unnecessary.

distribution

The main distribution area of the pest management was in Oldenburg , Osnabrücker Land , East Friesland and the Emsland as well as the neighboring Dutch provinces, i.e. areas of sandy, sterile old moraine soils . Here the ash floors reach their greatest thickness, sometimes over 1 m. In a lower density and with less thickness of the ash, pest fertilization was carried out in a much larger area. Plaggen soils occur in the south as far as the Belgian region , the Ruhr area , Braunschweig and the Altmark , and in the north as far as Jutland .

Plague extraction

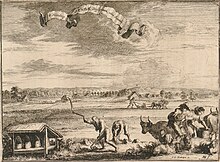

The first step in pest fertilization was pest extraction. For this, the uppermost humus-rich area of a soil had to be removed manually together with parts of the vegetation on it ( plagging , plagging ). The plagues were taken from the surrounding, often common property ( common land , common land ). These were mostly pagans (Heideplaggen). Some of them also came from forests (forest plagues); less often from meadows (lawn plagues).

The plague stabbing was a time consuming and difficult job.

Fertilizing the ash

The pests were used as litter, instead of or in combination with straw, in the barn, composted and finally spread on the fields. Together with the manure and kitchen waste, the material formed an organic fertilizer. More rarely, plagues were applied directly to the fields without using them as litter.

Usually the same areas were always plagued. Since pests consist mainly of soil, they had a high mineral content. Thus, the plagued fields ( Plaggenesche ) grew at a rate of about one millimeter per year and are in some cases characterized by a soil level that is sometimes over 1 m higher with abrupt changes in height at the edges, the ash edges .

Areas that have been plagued for a long time also have greatly increased humus contents of up to 7 % by weight and very high phosphorus contents . Today, plagued soils achieve soil values of 30 to 40, which are twice as high as the original soil. The high ground level also facilitated drainage .

On the Eschfeld fields mostly permanent cultivation with winter rye was carried out. This type of farming is also known as “eternal rye cultivation”, as rye has been grown in a field for 20 years in some cases, and in exceptional cases for 40 years, without interruption due to fallow land or crop rotation .

Land degradation and heather economy

The pest management brought about a significant improvement in the soil properties on the fertilized areas. However, it had devastating effects on the plague extraction areas, which were often used for decades or centuries. The soils, which were regularly “de-plagued”, were seriously affected by soil degradation . Shortly after they were plucked, they were exposed to wind erosion without a protective cover of plants . Drifts with drifting sands and even dune formation were the result. The regeneration of plundered areas took 20 to 40 years. As a rule, however, this period was not observed, as a result of which erosion damage and impoverishment progressed rapidly.

As a result of the misuse and overuse , large areas of completely impoverished heathland were created which could only be used extensively and are still unsuitable for agriculture . The sterile final stage of soil development , the Podzol , formed in the heather . In the late period of the heather farming economy , probably only about a third of the heather areas were suitable for sheep pastures, the rest was more or less devastated by the extraction of pests and consisted of partly open sands.

The end of pest management

Plague extraction was carried out in north-west Germany, Jutland and in the eastern Netherlands until the middle of the 19th century, and in some cases until the 1930s, on areas not used for arable farming. With the advent of mineral fertilizers , this labor-intensive method became obsolete and quickly abandoned.

Similar shapes

“Concentration economy”, in which plant nutrients were deliberately removed from areas remote from settlement and applied to arable land, was already practiced on nutrient-poor soils in the Neolithic Age . In the Iron Age on the Eiderstedt peninsula, for example, silt from the nearby mudflats was applied to the fields. Large amounts of soil were also applied to the so-called Celtic Fields . In the Middle Ages, a modified form of pest fertilization was known in the Eifel , the Sauerland and the Rhenish Slate Mountains : on the green areas used as common land, the soil was plowed at longer intervals and burned together with also removed shrubs. The ashes were then applied to the fields to be used for arable farming for a period of two to three years. This field-heather alternation gave rise to a form of heather known as broom heather .

literature

- Karl-Ernst Behre : On the medieval plague economy in northwest Germany and adjacent areas after botanical studies . In: Heinrich Beck , Dietrich Denecke , Herbert Jankuhn (Hrsg.): Investigations into the Iron Age and early medieval corridors in Central Europe and their use (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, No. 116). Part 2. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1980, ISBN 3-525-82396-7 , pp. 30-44.

- Helmut Jäger : Land use systems (field systems) of the early days . In: Heinrich Beck, Dietrich Denecke, Herbert Jankuhn (Hrsg.): Investigations into the Iron Age and early medieval corridors in Central Europe and their use (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, No. 116). Part 2. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1980, ISBN 3-525-82396-7 , pp. 197-28.

- Helmut Kroll: Prehistoric Plaggen Soils on the North Frisian Islands. In: Heinrich Beck, Dietrich Denecke, Herbert Jankuhn (Hrsg.): Investigations into the Iron Age and early medieval corridors in Central Europe and their use (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, No. 116). Part 2. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1980, ISBN 3-525-82396-7 , pp. 22-29.

- Wilhelm von Laer: Plague fertilization or marl? Münster 1865 ( ULB Münster ).

- Fritz Scheffer : The floor - a dynamic system. In: Heinrich Beck, Dietrich Denecke, Herbert Jankuhn (Hrsg.): Investigations into the Iron Age and early medieval corridors in Central Europe and their use (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, No. 116). Part 2. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1980, ISBN 3-525-82396-7 , pp. 7-21.

Web links

- Plague management in the juniper heaths of the Eastern Eifel

- Pest management and pest floors in Westphalia

Individual evidence

- ↑ Till Kasielke: Late Quaternary Landscape Development in the Upper Emscherland , dissertation, presented at the Geographical Institute (Faculty of Geosciences) of the Ruhr University Bochum 2014, p. 166, available online , (PDF)