Priap worms

| Priap worms | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Priapulida | ||||||||||||

| Théel , 1906 | ||||||||||||

| Orders | ||||||||||||

|

As priapulida (Priapulida) is called a root worm-shaped molting animals (ecdysozoan) with thickened trunk-like head who live all in or on the seabed. Their closest relatives are probably the hookweed (Kinorhyncha) and corset animals (Loricifera), with which they are grouped together in a taxon Scalidophora . Because of their appearance reminiscent of the male sexual organ, they are named after the Greek god of manhood, Priapus , who is usually represented with an enormous penis . They were first mentioned by Carl von Linné in his work Systema Naturae as Priapus humanus , translated "human penis".

The priap worms are a species-poor strain with 19 known species.

construction

Priapsworms usually have a plump, cylindrically shaped body, the length of which is between 0.05 centimeters for Tubiluchus corallicola and 39 centimeters for Halicryptus higginsi . Although of circular cross-section, the internal organs are arranged symmetrically on both sides.

Outer shape

At the front end the animals have a short, trunk-shaped "head", which is also known as a proboscis or introvert . Behind this is the trunk, which is superficially divided into 30 to 100 rings, but which is not internally segmented. It is covered by thorns containing chitin, the scalids , as well as numerous dimples and papillae, all of which probably serve as sensory receptors. The thorns are also used for locomotion. They occur particularly frequently, usually in the form of thorny hooks, in the pharynx region on the introvert, where they are arranged in several longitudinal rows and are probably also used to catch prey.

There may also be hooks at the rear end; they probably serve for locomotion. Some species also have either a long, retractable tail, which is presumably used for anchoring in the sediment, or one or two tufted tail appendages. The latter occur particularly in animals that live in low-oxygen sediments; they are therefore more likely to be used for gas exchange, perhaps also to regulate the salt balance or to perceive chemical substances.

Skin, muscles and pseudocoeloma

The body wall is a skin muscle tube, which consists of a chitin-containing non-cellular outer skin, the cuticle , an inner skin known as the epidermis and two layers of striated muscles . The cuticle is composed of an external, collagen- containing epicuticle , an exocuticle made up of proteins , and a chitin-containing endocuticle and is skinned regularly. The epidermis consists of a single layer of cells; Below it is a layer of circular muscles, which is followed by another layer of longitudinal muscles. At the front end there are also two groups of specialized longitudinal muscles, the introvert retractor muscles , which enable the worm to pull the introvert into the trunk and thus protect it.

The body cavity is located between the innermost muscle layer and the digestive tract and associated muscles. For a long time it was considered a true coelom , i.e. a fluid-filled cavity bounded by epithelial tissue that emerges from cells of the mesoderm during embryonic development . However, according to more recent findings, it is probably not covered by its own cell layer and thus represents a so-called pseudocoeloma ; the only exceptions are the gonads and perhaps also the throat, which are apparently surrounded by a real coelom. The pseudocoeloma is filled with a liquid in which, in addition to amoeboid phagocytes, also circulate pink blood cells that contain the oxygen-binding blood pigment hemerythrin and are therefore called heme erythrocytes . They presumably allow the worms to stay in their partially oxygen-free ( anoxic ) habitat. In addition to its function in the transmission of nutrients and gases through the body, the pseudocoeloma also serves as a hydrostatic supporting skeleton.

Digestive and excretory organs

The digestive tract begins with the mouth, which is followed by a muscular throat with numerous "teeth" on the inside. It can be turned inside and out and in the latter state is also known as the mouth cone - the teeth then come to lie on the outside. Behind the throat there is sometimes a further cavity, the polythyridium , which probably serves as a gizzard to further crush the food, which is then taken up in the midgut , which is filled with numerous invaginations, the microvilli . Unusable residues get into a short rectum that ends in the terminal anus. The entire digestive tract is surrounded by two muscle layers, the internal circular muscles and the external longitudinal muscles.

The excretion of liquid waste takes place through two tufted organs arranged in pairs, which are called protonephridia and are suspended from special ligaments, the mesenteries , in the rear trunk to the left and right of the intestine . They consist of fine tubes at the end of which are at least two single ciliate cells, the solenocytes . Together with the ovum or spermatic duct emanating from the cylindrical gonad, they flow into a common urogenital tract , which is connected to the outside world through small openings, the nephridiopores , at the end of the trunk.

Nervous system and sensory organs

The nervous system consists of a ring of nerves that runs around the mouth at the front end of the head. A simple, unpaired, ganglion-free nerve cord pulls back from it in the middle of the abdomen, from which ring nerves branch off at regular intervals. It itself ends in a tail ganglion .

The sensory perception is served by the countless dimples ( flosculi ), knobs ( papillae ) and thorns ( scalids ), which are hollow and each house a simply flagellated sensory nerve cell.

distribution and habitat

The larger priapsworm species only live in the cold circumpolar waters of the Arctic and Antarctic , on the coasts of North America east to about the height of the US state of Massachusetts , west to about central California and in the North and Baltic Seas ; from the south also around the Argentine Patagonia . The smaller species, especially from the Tubiluchidae family, are found in marine waters around the world, including the tropics , especially in the Caribbean and off the coasts of Central America .

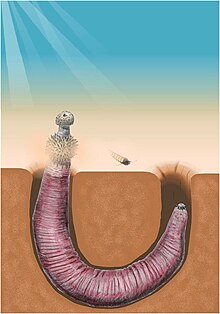

All animals live benthically , i.e. on the sea floor, where they burrow into low-oxygen sediments in such a way that their mouths lie on the surface of the sediment. They occur from the intertidal zone to about 500 meters water depth; some species can be found in the Wadden Sea or in the brackish water off river mouths. The smaller species also live interstitially in the gaps between the fine grains of shell or coral sand.

The species Halicryptus spinulosus has found a special ecological niche , which lives in almost oxygen-free ( anoxic ), sulfide-saturated sediments of the Baltic Sea and is evidently able to tolerate large concentrations of this poison or to degrade it within its own body.

In particular, the larger worm species are now primarily specialized in habitats that are poor in species and therefore less competitive and only play a subordinate role in ecological terms compared to other inhabitants of the seabed.

Diet and locomotion

The larger species are all prey on invertebrates with soft bodies like Vielborstern (Polychaeta), but also other Priapswürmern. They lie in wait for their prey buried in the sediment, grab it with the thorny hooks of their introvert and push it as a whole further and further into the throat by constantly turning the cone of the mouth in and out, where it is chopped into small pieces by the fine teeth. When the cone of the mouth is everted, the teeth come out and thus help to grasp the prey safely.

The smaller species, on the other hand, tend to feed on organic waste and the bacteria it contains. Maccabeus may filter nutrients out of the water, but does not seem to generate a breath water flow like other filter feeders. Lined living tubes like those created by other marine worms are unknown to the Priap worms.

Priapworms move forward with the help of their proboscis introverts and can dig into soft sediments, albeit with difficulty in adult animals, by alternately anchoring their anterior and posterior regions of the body.

At the beginning of a cycle, the body is thickened at the rear end by relaxing the circular muscles there and in this way forms the so-called penetration anchor . The rest of the ring muscle contracts, however, and thus reduces the cross-section of the body. Since the liquid in the pseudocoel is practically always the same volume, the introvert and throat protrude forward when the longitudinal muscles are relaxed. The fact that more and more fluid is now getting from the trunk into the introvert as a result of a wave-like contraction of the circular muscles starting from the rear end, the introvert expands considerably and in turn anchors the body at the front. By contraction of the longitudinal muscles and the introvert retractor muscles, the rest of the body is pulled forward so that after a new penetration anchor has been built up at the rear end, the cycle can start over.

Reproduction and development

Priapworms are separate-sex animals, although males and females can usually not be distinguished. No males are known in the genus Maccabeus , so it is likely to reproduce parthenogenetically , i.e. without a fertilization process.

In the larger species, seeds and small eggs with a relatively high yolk content are usually released in late winter and fertilized externally. Usually the males first release their germ cells into the sea water, then the females. In the smaller species, internal fertilization may also occur in the female's body.

In one species ( Meiopriapulus fijiensis ), the animals develop directly, but mostly via a larval stage that is also living on the ground . The trunk of the larvae is covered by a corset, the lorica , made of ten cuticle plates, one on the belly and one on the back, three on each side and two smaller ones at the front end (hence the name "loricate" larva). As with the adult animals, the front end of the larvae is designed as an introvert and can be pulled into the trunk. At the rear end there are special "toes" that are provided with glue glands and probably serve to attach to the sediment. Before the metamorphosis , i.e. the transformation into an adult animal, the larva passes through numerous moults, during which the lorica is also renewed. During the complex development phase, which can possibly last up to two years, it probably feeds on detrivores , i.e. on organic waste. At the end of this time there is the metamorphosis itself, in which the Lorica is lost; However, molting continues to take place in the adult animals.

Tribal history

Comparisons with modern taxa see the closest relatives of the priap worms quite clearly in the hookweed (Kinorhyncha) and corset animals (Loricifera) with which they form the taxon Scalidophora. The three groups share numerous features, such as the outer skin reinforced with chitin , the chitin-containing bristles or spikes on it, dimples (flosculi) serving for sensory perception and two groups of introvert-retractor muscles that attach to the front of the brain.

Which of the two animal phyla represents the evolutionary sister group is, however, much more controversial; all three possible combinations have been proposed and justified by zoologists. The presence of a corset formed by the cuticle, which is present in the former in the larval stage, suggests a closer relationship between priap worms and corset animals, while the fact that the pharyngeal tissue does not consist of epithelial muscle cells, but of itself, suggests a close relationship between priapses and hookweed embryonic mesoderm . The third alternative, a sister taxon relationship between hookweed and corset animals with the priap worms as the outer group, is justified by the protruding, but not everting, cone of the mouth of the first two taxa.

Embryo fossils of the species Markuelia hunanensis have been known from Hunan in southern China since 2004 . They come from the geological epoch of the middle to late Cambrian about 500 million years ago and are regarded by a cladistic analysis as representatives of the lineage of the Scalidophora, so they cannot be assigned to any of the three modern groups that make up this taxon. Markuelia hunanensis was possibly segmented - if this finding and at the same time the cladistic analysis were to be confirmed, the loss of segmentation would be a common derived characteristic ( synapomorphism ) of both the priapic worms and the corset animals and would thus underline their sister-group relationship.

The further relationship of the priap worms includes round worms (Nematoda) and string worms (Nematomorpha), with which the Scalidophora form the taxon Cycloneuralia. All of them are classified in the molting animals (Ecdysozoa), to which the Panarthropoda with the arthropods (Arthropoda) are counted as the most important group.

Fossil lore

Unlike most soft-bodied animals, the priapworms are also known to be fossilized; so far, at least eleven species have been described, which are formally divided into seven genera . They can already be found in the Canadian Burgess schist , which was formed 530 million years ago in the geological epoch of the middle Cambrian , so they have been preserved from the beginning of the modern aeon, the Phanerozoic .

Along with the arthropods, priapworms were the most important group of invertebrates in the Cambrian and were the dominant predatory worms of the seabed until the Ordovician . In the early Cambrian Maotianshan fauna from China, they make up the most common group with over 40% of the individuals and are more common here than the (albeit more species-rich) arthropods. The most common genus in the entire coenosis lived as a largely immobile predator / scavenger, partially buried in the substrate. Eight other genera shared this lifestyle. The second most common genus lived as a small burrowing sediment eater. The early Cambrian priapulids show some similarities in the way of life and nutrition with the recent forms, from which they differ mainly in the frequent occurrence on the "normal" seabed, while the modern forms are more limited to extreme habitats. Only with the appearance of pine- reinforced polychaeta from the ranks of the annelid worms did the priapulids lose their ecological importance and largely disappeared from the fossil record by the Silurian , which is why priapulids are already considered to be "basic failure", i.e. an (evolutionary) failure were seen. Only one other fossil genus, Priapulites , could be described from the later geological epoch of Carboniferous ; it can already be classified in the modern family Priapulidae.

The fossil-preserved species, like their modern relatives, lived predatory as part of benthos , i.e. the soft, muddy seabed. The eight-centimeter-long species Ottoia prolifica , the frequency of which is already expressed in the scientific name, lay in wait for hyolithids (Hyolitha), strange, worm-like, now extinct animals of the Paleozoic Era , which are relatives of the arm pods (Brachiopoda). Remnants of conspecifics in the intestines of Ottoia prolifica also indicate cannibalism . In addition to Ottoia , species of the genera Corynetis and Anningvermis from the Maotianshan slate of China already had gullet teeth and they also had tail appendages.

In tribal history, the fossil species (with the exception of Priapulites ) probably form the sister group of the modern species, as a systematic analysis showed. The species Corynetis brevis , Anningvermis multispinosus , Acosmia matiania , Paraselkirkia sinica and Xiaoheiquingella peculiaris have not yet been included in this:

| Priapulida (Priapulida) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The genera designated as Paleoscolidea were not counted among the priap worms for a long time and were allied with various other animal groups; but according to the modern view there is no reason to systematically differentiate them from the other fossil forms. In contrast to the other forms, the body of the sexually mature animal was covered with platelets (scalids) of different shapes and sizes. On the other hand , two genera traditionally counted among the Priap worms, Ancalagon and Fieldia , probably do not belong to this group, but are possibly representatives of the stem line of all Scalidophora.

Priap worms as paleontological model organisms

Due to the comparatively frequent occurrence of fossil priap worms in Cambrian sediments, they are well suited for investigating macroevolutionary questions. An important problem with regard to the evolutionary history of multicellular animals (Metazoa) concerns, for example, the nature of the so-called Cambrian radiation . This is a period of only a few million years in the Cambrian, during which numerous modern taxa appeared for the first time, with their basic plans, some of which differed significantly in morphology . In addition to the question of the cause of this sudden "explosion", one is now interested in whether the morphological diversity within a given taxon was greater than it is today. The background to this question is the assumption expressed by some paleontologists that the Cambrian in the animal world was a time of "experimentation" with various body construction plans, of which only a few were subsequently able to establish themselves. Investigations on fossil arthropods support this thesis to a limited extent, but alone do not necessarily provide a representative picture.

For this purpose, the preserved priapworm fossils were analyzed phenetically : In contrast to the cladistic analysis, which serves to reveal the phylogenetic relationships and may only use common derived features in the formation of higher taxa, the "primitive" ones, i.e. those from a common ancestor, are also included Characteristics included in the investigation; it is therefore particularly suitable for quantitative comparisons of the morphological types of two groups. The result of a phenetic investigation is the positioning of all species in a multi-dimensional space, which is technically referred to as "morphospace". Each type corresponds exactly to one point in this space; the distance between two points reflects the degree of morphological differences between the two associated species. By connecting each point with its closest neighbor, a network is finally created that shows the extent of structural similarity (but not necessarily ancestral relationship).

The investigations showed that all Cambrian forms in the "morphospace" form a close group, a so-called "cluster". The only line running out of the cluster connects it with the genus Priapulites , which comes from the carbon , to which the modern forms are connected. However, these do not form a cluster, but two very far apart groups, which are formed by the species of the family Tubiluchidae on the one hand and all other modern forms on the other. The latter themselves occupy a relatively diffuse area, so they are not concentrated in the "morphospace" either.

This result is interpreted today as follows:

- The morphological diversity of Cambrian forms is significantly smaller than it is today. At least in the case of the Priap worms, there can be no question of a post-Cambrian collapse of the wealth of forms.

- Contrary to popular belief, modern priap worms have clearly set themselves apart from their extinct ancestors in their structure. This is in contrast to results in the arthropods, in which the "morphospace" areas occupied by extinct and modern forms largely overlap. Priap worms therefore brought about essential morphological innovations after the Cambrian - which at least for this taxon refutes the thesis that the Cambrian was a special time of evolutionary "experiments", after which essential further developments of the "construction plan" through a tightly integrated genetic control of the embryological Development were severely restricted.

- The morphological changes may be related to the displacement of the priap worms from their original habitat into today's ecologically marginal areas. This thesis is supported by the fact that the species of the family Tubiluchidae, which are clearly separated from the other modern forms in morphological terms, also colonize another, much more life-friendly habitat.

Interestingly, the inclusion of (modern) forms of the hookweed and corset animals in the phenetic analysis resulted in a much closer morphological relationship to the extinct priapus worms - whether this indicates a much more conservative evolutionary development in these two groups of animals is unclear, however.

Systematics

A total of eighteen modern species are distinguished, which are divided into four orders within a class .

- The Priapulomorpha are the only order they have tail appendages and are in turn divided into two families, the large Priapulidae, whose males and females cannot be distinguished from one another, and the medium-sized Tubiluchidae, which show sexual dimorphism, i.e. a different appearance of the sexes. Unlike the other priap worms, the latter live in oxygen-rich, warm shallow waters of temperate and tropical zones with a high level of biodiversity. The Priapulomorpha are probably polyphyletic, i.e. an artificial group, so the two families are probably not sister taxa.

- The Halicryptomorpha are large predatory animals with no tail attachments. There is only one family, Halicryptidae with two species in the genus Halicryptus ; Halicryptus higginsi is the longest priaps worm ever.

- The Meiopriapulomorpha are a monotypical taxon, so they contain only one species, Meiopriapulus fijensis in the family Meiopriapulidae. The animals are smaller than two millimeters and have no teeth in their throats; They presumably feed detrivorically, i.e. on organic residues, and are viviparous with direct development of the larvae. They are the only species of this taxon to have a real histological coelom.

- The Seticoronaria finally, less than three millimeters in size, are believed filter feeders, absorb nutrients from the water. They have a characteristic row of hooks at the end of the trunk and a tentacle crown at the front end, which is probably also used for sensory perception. There is a genus Maccabeus with two species in a family Chaetostephanidae.

A proposed scheme of the phylogenetic relationships between the orders is shown in the following diagram:

| Priap worms |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

literature

- RC Brusca, GJ Brusca: Invertebrates. Second edition. Sinauer Associates, 2003, ISBN 0-87893-097-3 , p. 365.

- EE Ruppert, RS Fox, RD Barnes: Invertebrate Zoology, A Functional Evolutionary Approach. Seventh edition. Brooks / Cole, 2004, ISBN 0-03-025982-7 , p. 772.

Scientific literature

- RD Adrianov, VV Malakhov: Priapilida (Priapulida): Structure, development, phylogeny, and classification. KMR Scientific Press, 1996, p. 266

- X.-P. Dong, PCJ Donoguhe, H. Cheng, JB Liu: Fossil embryos from the Middle and Late Cambrian period of Hunan, south China. In: Nature. 427, 2004, p. 237.

- D.-Y. Huang, J. Vannier, J.-Y. Chen: Anatomy and lifestyles of Early Cambrian priapulid worms exemplified by Corynetis and Anningvermis from the Maotianshan Shale (SW China). In: Lethaia. 37, 2004, p. 21.

- V. Storch: Priapulida . In: FW Harrison, EE Ruppert (Ed.): Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates . Wiley-Liss, 1991, p. 333.

- MA Wills: Cambrian and recent disparity: The picture from priapulids . In: Paleobiology. 24, 1998, p. 177.

Individual evidence

- ^ TC Shirley & V. Storch (1999): Halicryptus higginsi n.sp. (Priapulida), a giant new species from Barrow, Alaska. Invertebrate Biology Vol.118, No.4: 404-413.

- ^ Peter Ax (2001): The system of Metazoa III. Spectrum, Heidelberg, 283 p.

- ↑ Stephen Q. Dornbos & Jun-Yuan Chen: Community palaeoecology of the early Cambrian Maotianshan Shale biota: Ecological dominance of priapulid worms. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 258 (2008): 200-212. doi : 10.1016 / j.palaeo.2007.05.022

- ↑ J. van der Land & A. Nørrevang (1985): Affinities and intraphyletic relationships of the Priapulida. in Conway Morris, S., George, JD, Gibson, R. & Platt, HM (eds.), The origins and relationships of lower invertebrates. The Systematic Association Special Volume 28. Clarendon Press, Oxford. pp. 261-273.