Psychedelic

As psychedelics are hallucinogens effective psychotropic substances referred to that higher doses of a psychedelic intoxication : (colloquially "Trip" ) may precipitate. Well-known and widely used psychedelics are LSD , cacti containing mescaline ( peyote , Echinopsis pachanoi etc.), mushrooms containing psilocybin and preparations containing dimethyltryptamine ( ayahuasca , yopo etc.). Ketamine is also sometimes referred to as a psychedelic , although primarily a dissociative with "non-classical" receptor effects, due to the subjective effects with complete dissociation (" K-Hole ").

Receptor action

The effect of psychedelics is primarily achieved by stimulating the 5-HT2A protomer in the 5-HT2A - mGlu2 receptor complex ; the 5HT2C receptor, and for some substances also the σ1 receptor , is stimulated (see also: functional selectivity for receptor Oligomers ).

Peculiarities of psychedelic intoxication

Under the influence of psychedelic substances, perception and conceptual association can change greatly in all aspects, whereby the awareness that one is in a state of intoxication is usually not lost. Currently processed, stored as memories or ideas as well as archetypal consciousness contents can be visually or acoustically manifest. The unreal nature of these illusions and pseudo-hallucinations is always recognized. The changed association can result in surprising twists and turns of the perceived and the intoxication itself and evoke inner experiences perceived as insightful, up to life-changing spiritual experiences. Therefore, psychedelics are usually classified as entheogens .

A phenomenological description of intoxication itself is not possible; Ultimately, a psychedelic high is always a highly subjective experience that can only be conveyed superficially in terms of language, and the neurochemical basics have only been partially researched. A central component is the visionary restructuring, the change in thinking and association towards the pre-verbal, combined with the manifestation of the unconscious in all aspects of perception. The disruption of the normal function of certain control loops controlled by the serotonin system plays an important role here , as a result of which the filter function of the thalamus is omitted and the frontal lobe is also flooded with neuro-excitatory glutamate . Another fundamental aspect of intoxication is the (euphoric or fearful) ego dissolution or oceanic self-delimitation, the abolition of the boundaries between the ego and the outside world. The changed release of neurotransmitters leads to an overactivation of the locus caeruleus in the midbrain. The subsequent release of norepinephrine throughout the brain creates a state of extreme alertness and mental transcendence .

External stimuli (e.g. music), but also internal stimuli, such as one's own thoughts and feelings, can make a wide variety of contents manifest in perception on a psychedelic intoxication or change what is already manifest, whereby the contents become increasingly visual in the case of intense intoxication appear. In principle, this mechanism makes the intoxication controllable over long distances and enables work with the self, provided that attention is focused on it. However, many possible changes in perception are also of a purely neurological nature, such as "morphing" (bending or shaking of objects) due to impaired pattern and edge recognition, abstract geometric effects due to interference in the visual pathway or changes in the pitch of music being heard. Particularly strong noises can also lead to an overinterpretation of the patterns seen, whereby objects that are not actually present are perceived, but recognized as illusions.

In summary it can be said that the psychedelic drug intoxication represents a state of fully preserved wakefulness under the circumstances of a brain-wide reorganized, relaxed cognition . The psychedelic state is also discussed within the Integrated Information Theory .

Psychedelic substances

Psychedelics include:

- hallucinogenic tryptamines : e.g. B. Psilocybin , Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) (present in Ayahuasca ), 5-MeO-DMT , α-MT , 4-HO-DIPT etc.

- hallucinogenic phenylethylamines : e.g. B. Mescaline , 2C-B , 2C-I , 25I-NBOMe , DOB , DOM , TMA , Bromo-DragonFLY etc.

- hallucinogenic ergolines : e.g. B. LSD , ALD-52 , 1P-LSD , 1B-LSD , 1CP-LSD , AL-LAD , ETH-LAD , LSH , Ergin (LSA) etc.

- in high doses, the effects are sometimes different Dissoziativa associated with the psychedelic, although no 5HT2A receptor effect is: ketamine , METHOXETAMINE (MXE), dextromethorphan (DXM) and Salvinorin A .

Mushrooms containing psilocybin contain psilocybin and psilocin

Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a naturally occurring tryptamine - alkaloid

Ayahuasca preparation

DOB - Blotter

Health and psychedelic substances

Statistical research

In a retrospective cross-sectional study (2013) of patient information in questionnaires from 2001 to 2004, a possible statistical connection between medical treatment within the past year for psychological or psychiatric problems and at least one intake of one of the "classic" psychedelic substances ( LSD , psilocybin , Mescaline / peyote ) throughout life. The National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) records, conducted by the U.S. Department of Health, provided data from 130,152 such patients for this period. Of these, 21,967 stated that they had consumed one of the substances mentioned at least once in their life. A statistically significant relationship between the examined variables was not found. The authors concluded that taking a “classic” psychedelic substance at least once throughout life was not an independent risk factor for psychological problems in the past year. However, they pointed out that a study of this type did not give any indications of possible causal relationships.

In a similar analysis (2015) of questionnaires from the normal population from 2008 to 2012 (also by the NSDUH), a possible statistical connection between the occurrence of a mental stress state within the past month and the occurrence of suicidal tendencies within the past year and at least one one-time intake of a “classic” psychedelic substance (LSD, mescaline and psilocybin) throughout life. Of the 191,382 answer sheets, 27,235 stated that one of the substances had been taken at least once within the previous year. This group of people showed a statistically significantly reduced risk of the mentioned psychological stress and suicidal tendency. However, the authors point out that certain personality traits could result in both increased interest in the substances mentioned and a reduced risk of stress. The fact that the consumption of the substances resulted in general health protection cannot be concluded from the data. According to the authors, further investigations, especially with regard to possible medical applications, are desirable, however:

"Growing evidence including the present research suggests that classic psychedelics may have the potential to alleviate human suffering associated with mental illness."

"An increasing body of evidence, including current research, suggests that classic psychedelics may have the potential to alleviate the human suffering associated with mental illness."

Possible medical application

Examples of potential medical applications are the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety disorders in patients with terminal illnesses that are terminally fatal. Furthermore, the effectiveness of psychedelic substances in depression and addiction disorders caused by psychotropic substances ( alcohol , tobacco , cocaine ) are examined in more recent studies .

Possible dangers

Under unfavorable conditions, psychedelic substances can trigger temporary episodes of fear (horror trip ) or psychosis ( substance-induced psychosis ). Further psychological disorders such as the abuse of hallucinogens and persistent perceptual disorder after hallucinogen use (HPPD) are included as a diagnostic category in the DSM-IV .

Microdosing

The low dose of psychedelics in the threshold range below or within the effective dose is called microdosing or mini dosing .

literature

- Adam L. Halberstadt, Franz X. Vollenweider, David E. Nichols: Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs . Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-662-55880-5 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- M. von Heyden, H. Jungaberle: Psychedelics. In: M. von Heyden, H. Jungaberle, T. Majić (eds.): Handbook of Psychoactive Substances . Springer Reference Psychology. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg, 2018, ISBN 978-3-642-55124-6 , pp. 669-682, doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-642-55125-3_43 .

- FX Vollenweider, KH Preller: Neurobiological basics of the effects of psychedelics. In: M. von Heyden, H. Jungaberle, T. Majić (eds.): Manual Psychoactive Substances . Springer Reference Psychology. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg, 2018, ISBN 978-3-642-55124-6 , pp. 423-436, doi: 10.1007 / 978-3-642-55125-3_70 .

- Robin L Carhart-Harris, Guy M Goodwin: The Therapeutic Potential of Psychedelic Drugs: Past, Present and Future. In: Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017, doi: 10.1038 / npp.2017.84 . (Review).

- DE Nichols: Psychedelics. In: Pharmacological reviews. Volume 68, Number 2, April 2016, pp. 264-355, doi: 10.1124 / pr.115.011478 , PMID 26841800 (review).

- RG dos Santos, FL Osorio u. a .: Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. In: Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 2016, doi: 10.1177 / 2045125316638008 .

- KW Tupper, E. Wood, R. Yensen, MW Johnson: Psychedelic medicine: a re-emerging therapeutic paradigm. In: CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. Volume 187, number 14, October 2015, pp. 1054-1059, doi: 10.1503 / cmaj.141124 , PMID 26350908 , PMC 4592297 (free full text) (review)

- A. Szabo: Psychedelics and Immunomodulation: Novel Approaches and Therapeutic Opportunities. In: Frontiers in immunology. Volume 6, 2015, p. 358, doi: 10.3389 / fimmu.2015.00358 , PMID 26236313 , PMC 4500993 (free full text) (review).

- Ben Sessa: Turn on and tune in to evidence-based psychedelic research . (PDF) In: The Lancet Psychiatry. 2, 2015, p. 10, doi: 10.1016 / S2215-0366 (14) 00120-5 .

- T. Majić, TT Schmidt, J. Gallinat: Peak experiences and the afterglow phenomenon: when and how do therapeutic effects of hallucinogens depend on psychedelic experiences? In: Journal of psychopharmacology. Volume 29, Number 3, March 2015, pp. 241-253, doi: 10.1177 / 0269881114568040 , PMID 25670401 (review).

- D. Baumeister, G. Barnes, G. Giaroli, D. Tracy: Classical hallucinogens as antidepressants? A review of pharmacodynamics and putative clinical roles. In: Therapeutic advances in psychopharmacology. Volume 4, number 4, August 2014, pp. 156-169, doi: 10.1177 / 2045125314527985 , PMID 25083275 , PMC 4104707 (free full text) (review).

- B. Rolland, R. Jardri, A. Amad, P. Thomas, O. Cottencin, R. Bordet: Pharmacology of hallucinations: several mechanisms for one single symptom? In: BioMed research international. Volume 2014, 2014, p. 307106, doi: 10.1155 / 2014/307106 , PMID 24991548 , PMC 4065763 (free full text) (review).

Web links

- Psychedelics: Lifting the veil, Robin Carhart-Harris, TEDxWarwick on YouTube , April 14, 2016

- Media library: "Highlung" through drugs? In: 3sat.de. May 24, 2012, accessed September 9, 2016 . - Research with hallucinogenic drugs has been taboo for decades. There are now a few researchers worldwide who have taken up the trail of hallucinogens again and have gained new knowledge.

- scobel - drugs as medicine. From the illegal drug to the remedy: Will psychedelic substances such as LSD or "magic mushrooms" soon be used as medicines for depression, anxiety disorders and pain? 3sat / ZDF. 2019 (58 min).

- Hallucinogen Research in Humans - Neuro Culture Lab. In: neuroculturelab.com. January 1, 2011, accessed August 27, 2016 .

- The Psychedelic Library - Collection of basic texts on psychedelics and the history of psychedelics research

- PsychonautWiki - Wiki about mind-expanding drugs and their subjective effects

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Richard K. Ries, Shannon C. Miller, David A. Fiellin: Principles of Addiction Medicine In: M - Medicine Series . Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7817-7477-2 . P. 231ff.

- ^ Jan Dirk Blom: A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4419-1223-7 . P. 148f.

- ^ A b D. E. Nichols: Psychedelics. In: Pharmacological reviews. Volume 68, number 2, April 2016, pp. 264–355, doi: 10.1124 / pr.115.011478 , PMID 26841800 , PMC 4813425 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ JL Moreno, C. Muguruza et al. a .: Identification of three residues essential for 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A-metabotropic glutamate 2 (5-HT2A mGlu2) receptor heteromerization and its psychoactive behavioral function. In: The Journal of biological chemistry. Volume 287, number 53, December 2012, pp. 44301-44319, doi: 10.1074 / jbc.M112.413161 , PMID 23129762 , PMC 3531745 (free full text).

- ↑ JL Moreno, T. Holloway, L. Albizu; SC Sealfon, J. González-Maeso: Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptor is necessary for the pharmacological and behavioral effects induced by hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists . In: Neurosci. Lett. tape 493 , no. 3 , 2011, p. 76–79 , doi : 10.1016 / j.neulet.2011.01.046 , PMID 21276828 , PMC 3064746 (free full text).

- ↑ I. Raote, A. Bhattacharya, Panicker MM: serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) Receptor Function: Ligand-Dependent Mechanisms and Pathways. In: A. Chattopadhyay (Ed.): Serotonin Receptors in Neurobiology. CRC Press, 2007, Chapter 6. PMID 21204452

- ↑ J. González-Maeso, RL Ang, T. Yuen and a .: Identification of a serotonin / glutamate receptor complex implicated in psychosis . In: Nature . tape 452 , no. 7183 , 2008, p. 93-97 , doi : 10.1038 / nature06612 , PMID 18297054 , PMC 2743172 (free full text).

- ^ Thomas S. Ray, Olivier Jacques Manzoni: Psychedelics and the Human Receptorome. In: PLoS ONE. 5, 2010, p. E9019, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0009019 .

- ^ RR Griffiths, WA Richards, U. McCann, R. Jesse: Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance . In: Psychopharmacology . tape 187 , no. 3 , August 2006, p. 268 , doi : 10.1007 / s00213-006-0457-5 .

- ↑ Stephan Schleim: Spirituality at the push of a button? Telepolis , July 24, 2006, accessed January 3, 2013 .

- Jump up ↑ Drug Induced and Other Exceptional States of Mind - Eve & Rave

- ↑ Edelrausch in the laboratory ( Memento of the original from January 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. - Neuro Culture Lab

- ↑ Entopic Hallucination - Psychedelic Information Theory

- ^ Andrew R. Gallimore: Restructuring consciousness - the psychedelic state in light of integrated information theory. In: Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 9, 2015, doi: 10.3389 / fnhum.2015.00346 .

- ^ Psychedelic Effects of Ketamine in Healthy Volunteers. Retrieved October 7, 2016 .

- ^ Ketamine associated psychedelic effects and dependence. Retrieved October 7, 2016 .

- ^ Henry R. Kranzler, Domenic A. Ciraulo, Leah R. Zindel: Clinical Manual of Addiction Psychopharmacology , 2nd Edition, American Psychiatric Pub, 2014. ISBN 978-1-58562-528-4 . P. 268.

- ↑ KA MacLean, MW Johnson, CJ Reissig, TE Prisinzano, RR Griffiths: Dose-related effects of salvinorin A in humans: dissociative, hallucinogenic, and memory effects. In: Psychopharmacology. Volume 226, number 2, March 2013, pp. 381-392, doi: 10.1007 / s00213-012-2912-9 , PMID 23135605 , PMC 3581702 (free full text).

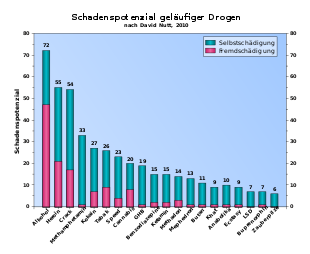

- ↑ David J Nutt, Leslie A King, Lawrence D Phillips: Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. In: The Lancet. 376, 2010, pp. 1558-1565, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61462-6 .

- ↑ Drug Toxicity. Rober Gable, accessed December 14, 2015 .

- ↑ RS Gable: Acute toxicity of drugs versus regulatory status. In: JM Fish (Ed.): Drugs and Society: US Public Policy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD 2006, pp. 149-162.

- ↑ Teri S. Krebs, Pål-Ørjan Johansen, Lin Lu: Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study. In: PLoS ONE. 8, 2013, p. E63972, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0063972 .

- ↑ a b P. S. Hendricks, CB Thorne, CB Clark, DW Coombs, MW Johnson: Classic psychedelic use is associated with reduced psychological distress and suicidality in the United States adult population. In: Journal of Psychopharmacology. 29, 2015, p. 280, doi: 10.1177 / 0269881114565653 .

- ↑ CS Grob, AL Danforth, GS Chopra, M. Hagerty, CR McKay, AL Halberstadt, GR Greer: Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. In: Archives of general psychiatry. Volume 68, number 1, January 2011, pp. 71-78, doi: 10.1001 / archgenpsychiatry.2010.116 , PMID 20819978 .

- ^ A b K. W. Tupper, E. Wood, R. Yensen, MW Johnson: Psychedelic medicine: a re-emerging therapeutic paradigm. In: CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. Volume 187, number 14, October 2015, pp. 1054-1059, doi: 10.1503 / cmaj.141124 , PMID 26350908 , PMC 4592297 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ COMPASS Pathways Receives FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for Psilocybin Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression - COMPASS. Retrieved July 17, 2019 (American English).

- ↑ M. Winkelman: Psychedelics as medicines for substance abuse rehabilitation: evaluating treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine and Ayahuasca. In: Current drug abuse reviews. Volume 7, Number 2, 2014, pp. 101-116, PMID 25563446 (Review).

- ↑ Jan Dirk Blom: A Dictionary of Hallucinations , Springer Science & Business Media 2009, ISBN 1-4419-1223-1 , p. 310.

- ↑ Ralph E. Tarter, Robert Ammerman, Peggy J. Ott: Handbook of Substance Abuse: Neurobehavioral Pharmacology , Springer Science & Business Media 2013, ISBN 1-4757-2913-8 , p. 236.

- ↑ Review in: AL Halberstadt, MA Geyer: Serotonergic hallucinogens as translational models relevant to schizophrenia. In: The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum. Volume 16, number 10, November 2013, pp. 2165-2180, doi: 10.1017 / S1461145713000722 , PMID 23942028 , PMC 3928979 (free full text) (review).

- ^ JH Halpern, HG Pope: Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: what do we know after 50 years? In: Drug and alcohol dependence. Volume 69, Number 2, March 2003, pp. 109-119, PMID 12609692 (review).

- ↑ APA Diagnostic Classification DSM-IV-TR

- ↑ Kim PC Kuypers, Livia Ng, David Erritzoe, Gitte M Knudsen, Charles D Nichols, David E Nichols, Luca Pani, Anaïs Soula, David Nutt: Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. In: Journal of Psychopharmacology. 33, 2019, p. 1039, doi: 10.1177 / 0269881119857204 .