Radbruch's formula

The Radbruch formula is a thesis first formulated in 1946 by the German legal philosopher Gustav Radbruch (1878–1949). According to this theory has become a judge in a conflict between the positive (set) Law and justice always - and only then - against the law and instead of the material justice to decide if the law in question

- is to be regarded as “unbearably unfair” or

- the equality of all people, which is fundamentally laid out in the concept of law, is "consciously denied" from the point of view of the interpreter.

Since the Radbruch formula was used several times by the federal German supreme court jurisprudence , Radbruch's essay Legal injustice and supra-legal law , which contained this thesis for the first time, is considered by some authors to be the most influential legal philosophical text of the 20th century. The question of whether the right positivist legal term, which focuses solely on the proper setting and social effectiveness of a norm , should be modified in the sense of Radbruch's formula, is a fundamental controversy of the current legal philosophical discussion in Germany.

Content and structure

Content and different versions

Radbruch published the text passage, which has entered the history of legal philosophical ideas as the “Radbruch Formula”, for the first time in 1946 in the essay Legal Injustice and Supra-Legal Law in the Süddeutsche Juristerneitung. The name "Radbruchsche Formula", which is in use today, was first used in 1948 by Richard Lange .

If a judge finds himself in a conflict situation in which he vacillates between the possibilities of either applying a norm of positive law that appears unjust to him or rejecting it in favor of material justice (exceptional situation), then Radbruch suggests resolving the conflict as follows:

“The conflict between justice and legal certainty should be resolved in such a way that positive law, secured by statutes and power, takes precedence even if its content is unfair and inexpedient, unless the contradiction of the positive law to Justice has reached such an unbearable level that the law as “wrong right” has to give way to justice. It is impossible to draw a clearer line between the cases of legal injustice and the laws still valid despite their incorrect content; Another demarcation, however, can be made with all sharpness: where justice is not even striven for, where the equality, which constitutes the core of justice, was deliberately denied in the establishment of positive law, then the law is not just 'incorrect' law, rather, it lacks any legal nature at all. Because one cannot define law, including positive law, in any other way than an order and statute which, according to their meaning, is intended to serve justice. "

Radbruch presented this position in a very similar way in the posthumously published lecture notes on the Pre-School of Legal Philosophy :

Where the injustice of positive law reaches such a level that the legal certainty guaranteed by this law no longer weighs heavily against its injustice, this “incorrect” law takes precedence over justice.

Elsewhere in the same source it says:

“So where [...] justice is not even striven for, the orders thus created can only be judgments of power , never legal propositions [...]; so the law that denies certain people human rights is not a legal proposition. So here there is a sharp boundary between right and non-right, while as shown above, the boundary between legal injustice and applicable law is only a dimensional limit [...]. "

structure

Radbruch's formula distinguishes three types of unjust laws. The three types of law are contrasted with three statements about the legal validity of these laws:

- Positive laws need to be applied even when they are unfair and inexpedient.

- “Unbearable” unjust laws must give way to justice.

- If laws don't even aim to be fair, they are not a law.

The addressee of the Radbruch formula is jurisprudence. The formula initially postulates the following basic rule: For reasons of legal certainty, in principle , positive law also deserves preference over non-positive principles of justice if it turns out to be unjust. In this respect, Radbruch's position agrees with that of right-wing positivism . At the same time, Radbruch emphasizes that justice and legal security as demands arising from the “idea of law” are in principle equally important. Neither of these two sides of the legal idea deserves priority over the other. These are equal but potentially contradicting demands. These two premises - the principle of equality and the burden of conflict - lead Radbruch to a conclusion that deviates from legal positivism: the principle of legal certainty must at least take a back seat to the principle of justice if the injustice of the law in question exceeds a certain level, in Radbruch's words: " unbearable ”. Formulated in accordance with today's legal usage, positive law therefore only enjoys prima facie priority over deviating principles of justice , but not absolute priority.

Radbruch's formula is often summarized using the short form “extreme injustice is no right”. On closer inspection, it contains two separate and mutually independent sub-formulas, commonly referred to in secondary literature as the "unbearable formula" and the "denial formula".

The “unbearable formula” releases the judge from his fundamental commitment to positive law if he considers it to be unbearably unjust. In such cases, the principle primacy of positive law recedes and a written norm must also give way to material justice. Radbruch himself did not consider this variant of Radbruch's formula to be very clear-cut: the boundaries between “right”, “incorrect” and “unbearably incorrect” law are fluid and a question of the right measure that can only be drawn vaguely. With this weak variant of Radbruch's formula, the legal-theoretical status of the so-called “incorrect law” remains unclear: Are extremely unjust laws still to be regarded as “law” in the sense of the legal term? Radbruch himself did not commit to this. Newer interpretations of Radbruch's formula also exclude “unbearably unjust” law from a correspondingly modified legal term.

Radbruch judged more clearly the legal-theoretical status of a law to be rejected on the basis of the "denial formula": A law that does not even strive for justice is therefore not a law in the sense of the legal term. In contrast to the “unbearable formula”, the “denial formula” does not seem to be linked primarily to the properties of the law in question, but to the intentions of the legislature. Stanley Paulson and Ralf Dreier have therefore pointed out that in individual cases it would be difficult, at least, to prove such a deliberate denial of the principles of justice to the legislature. However, the prevailing view is that the denial formula is also amenable to objective interpretation . Recourse to the actual regulatory intentions of the legislature is not necessary. Rather, what is decisive is the “objective will of the legislature” in the wording of the law. In addition, the thesis is advocated that a subjective interpretation of the denial formula is missing from Radbruch's legal philosophy, since he also preferred the objective interpretation of the law (“purpose of the law”) over the subjective (“purposes of the legislature”) within his legal methodology .

According to their current representatives (currently in Germany: Robert Alexy , Ralf Dreier), Radbruch's formula assumes the epistemological possibility of objectively distinguishing between “just” and “unjust” laws. This epistemological possibility was denied by right-wing positivists such as Hans Kelsen or Alf Ross - but before 1945 also by Gustav Radbruch himself. H. L. A. Hart left the answer to this question open. In this regard, Radbruch himself took the view after 1945 that, in view of the centuries-long efforts to establish human rights, at least a core set of rights could be peeled out that only an “intentional skepticism” could really question. Sometimes it is pointed out that the Radbruch formula proceeds epistemologically in the way of falsification : The Radbruch formula does not try to positively determine what is fair ( verification ). It is limited to negatively determining which laws are "extremely unjust" in any case. This epistemologically negative procedure is said to be easier to carry out and subject to fewer objections than the opposite, positive procedure.

Position within the legal philosophy of Radbruch

The question of whether and to what extent Radbruch's formula marks a turning point in the legal philosophical thinking of its author is a lively subject of the current legal philosophical discussion. The formula did not appear in Radbruch's writings before 1945. Rather, he was still of the opinion in 1932 that the judge had to obey positive law without exception. This attitude was an expression of the value relativism advocated by Radbruch . Radbruch's value relativism is based on the strict logical distinction between being and ought :

"Obligatory sentences can only be justified and proven by other ought-sentences. Precisely for this reason the last sentences are unprovable, axiomatic, not capable of knowledge, but only of confession. "

This relativistic basic assumption led Radbruch to formulate the possibilities of the legal philosophy in a correspondingly modest way: The legal philosophy is not able to decide the conflict of different worldviews on the basis of objective arguments. The task of legal philosophy is to analyze and compare the basic values of the different worldviews, but not to establish a hierarchy between them. On the basis of this legal-philosophical relativism, Radbruch distinguished between three “no longer traceable” fundamental legal conceptions: the individualistic, the supra-individualistic and the transpersonal conception. The individualistic view represents the primacy of the individual and his needs over the whole. In the supra-individualistic view, individual needs only serve to create collective values and are inferior to them. According to the transpersonal view, both individual and collective needs are in the service of overarching cultural goals. According to Radbruch, all three legal views stand side by side on an equal footing. An argumentative compelling preference for one over the other is not possible.

The question of whether Gustav Radbruch essentially retained, modified or abandoned his system of legal philosophy based on value relativism with the introduction of Radbruch's formula after 1945 is answered differently. In the preschool of legal philosophy , first published in 1948, Radbruch made a distinction, as in 1932, between the individualistic, the supra-individualistic and the transpersonal legal conception. In addition, he did not consider the idea of ranking the three “value classes” to be feasible. Nevertheless, in contrast to 1932, he now recognized a relative priority of the individualistic legal conception: Both the transpersonal and the supra-individualistic legal conception would have to accept the validity of individual human rights. Collective and cultural values would have to recede if elementary human rights are violated. In every legal system there is therefore a certain amount of liberalism as a necessary element.

Nevertheless, Stanley Paulson, Ralf Dreier and Hidehiko Adachi advocate the so-called unity thesis: Radbruch's formula does not mean any significant change in the basic legal philosophical assumptions made by Radbruch before 1945. This thesis is based on various passages from Radbruch's work at the time of the Weimar Republic , in particular the second edition of the Philosophy of Law from 1932, which seem at least to prepare Radbruch's formula. As early as 1932, Radbruch suggested the existence of so-called "Shame Laws", which conscience refuses to obey. He cited the socialist laws as an example . According to the wording, Radbruch also anticipated the basic ideas of the "denial formula" in 1932. This results from his legal concept, according to which law is "that reality which has the purpose of serving justice".

On the other hand, it must be emphasized that before 1945 Radbruch adhered strictly to the principle that at least one judge had to apply every law regardless of whether he considered it unjust. In relation to the judiciary , he originally represented a definitive priority of positive law, which he only converted into a mere prima facie priority after 1945. For these reasons, the majority of the secondary literature is of the opinion that Radbruch modified his system of legal philosophy, which was developed before 1945, by means of Radbruch's formula, in any case not insignificantly. HLA Hart even spoke in this context of a "conversion" of Radbruch to the doctrine of natural law , while Lon Fuller identified a radical change ("a profound modification") within his system.

The Radbruch formula is often understood as Radbruch's reaction to the National Socialist system of injustice. Radbruch himself explicitly advocated the thesis that the positivism prevailing among the German judges at the time had made them defenseless against laws, no matter how unjust. This so-called “wheel break thesis” is now considered to be refuted. Neither at the time of the Weimar Republic nor later at the time of National Socialism , German jurisprudence and jurisprudence were predominantly oriented towards legal positivism. The viability of Radbruch's formula and its basic legal philosophical assumptions can therefore only be discussed independently of this premise.

Classification of the history of ideas

At first glance, the basic statement of the "formula" mentioned above seems to be traceable back a long way. Even in antiquity and in the Middle Ages, there were arguments that the state or its law should not be obeyed under all circumstances. For example, Augustine argued in terms of natural law: "An unjust law is (at all) no law." Similar statements can be found among the Stoics , especially Seneca , and Thomas Aquinas .

It would be a misunderstanding to interpret Radbruch's reference to “unbearably” unjust laws as an unqualified return to ideas about natural law. According to Radbruch's formula, only “unbearable” - today's supporters of Radbruch's formula use the term “extreme” - exclude unjust laws from the norms of applicable law. In all other cases, for reasons of legal certainty, the priority of application of positive law remains. It is precisely this reference to legal certainty that distinguishes Radbruch's formula from the natural law statements cited above. These do not take into account the principle of legal certainty, which the legal positivists consider important, but regard every unjust law as a non-law regardless of other principles. So Radbruch's formula is based on a compromise. Because of this compromise, the priority of application of positive law in principle, including against unjust and inexpedient laws, led Radbruch's pupil Arthur Kaufmann to classify his legal philosophy as “beyond natural law and positivism ”.

Radbruch was not the first legal theorist to give such considerations. In his book “Law and Judge's Rule” (1915), the legal theorist Hans Reichel dealt with various balancing problems that a judge can face in the process of finding the right law. Like Radbruch, Reichel also assumed a tension between the principles of legal security and material justice. His aim was to resolve this tension without giving up the principle of legal certainty. After he had established that the principle of legal certainty is normally paramount, he restricted this basic rule as follows:

“By virtue of his office, the judge is obliged to deliberately deviate from a statutory provision if that provision is in conflict with the moral feeling of the general public in such a way that compliance with the same would endanger the authority of law and statute considerably more than its disregard . "

In this way, Reichel did not take the key message of Radbruch's formula literally, but anticipated it accordingly. In contrast to Radbruch's formula, which emerged 30 years later, Reichel's statements were not received to any significant extent by either case law or legal theoretical discussions.

Reception through jurisprudence and legal philosophy

In Germany , both the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Court of Justice have applied Radbruch's formula several times. It also plays a major role in the international legal-philosophical discussion of the concept of law, the right to resist and murder of tyrants , although a clear distinction is not always made between the two types of formula, the intolerance formula and the denial formula.

Reception through the jurisprudence

The Radbruch formula has been used several times by the case law of the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Court of Justice . This first happened in the post-war period when dealing with various aspects of Nazi injustice, and more recently when assessing the criminal liability of the so-called wall riflemen after the collapse of the GDR .

post war period

In the first decades after the end of the Second World War , the question of the extent to which certain National Socialist regulations and laws - particularly offensive in the opinion of the German federal courts - were capable of including the jurisprudence of the Federal Republic of Germany as part of the application of Radbruch's formula came up to bind applicable law. The Federal Court of Justice and the Federal Constitutional Court consistently held the view that in any case evidently unjust regulations of the National Socialist legislature were irrelevant for the Federal German jurisprudence. In doing so, you explicitly referred to the principles of Radbruch's formula.

In its judgment of July 12, 1951, the Federal Court of Justice declared the shooting of a deserter on the run by a battalion commander of the Volkssturm to be illegal. The battalion commander cited a so-called disaster order from Heinrich Himmler to justify himself . This disaster order entitles anyone carrying a weapon to shoot people on the run without further ado. After initially criticizing the poor legal quality of the disaster order, the Federal Court of Justice relied explicitly on Radbruch to confirm its judgment:

“Even if this order had been promulgated as statute or ordinance, it would not be legally binding . The law finds its limit where it contradicts the generally recognized rules of international law or natural law (OGHSt 2, 271) or the contradiction of the positive law to justice reaches such an unbearable level that the law is called "incorrect law «To give way to justice. If the principle of equality in the establishment of positive law is denied at all, then the law lacks legal nature and is no law at all (Radbruch, SJZ 1946, 105 [107]). One of the inalienable rights of a person is that he must not be deprived of his life without trial. Even the ordinance on the establishment of court courts of February 15, 1945 (RGBl I, 30) still adhered to this legal principle. According to this, the so-called disaster order has no legal force. It is not a legal norm; its compliance would be objectively illegal "

The question of the liability of a formally correct adopted Nazi legal standard for West German courts and the related significance of Radbruch's formula, the Federal Constitutional Court dealt in his nationality decision of 14 February 1968. Specifically, it was about the 11th amendment to the Reich Citizenship Law November 25, 1941 :

"§ 2. A Jew loses German citizenship a) if he has his habitual residence abroad when this regulation comes into force, with the entry into force of the regulation, b) if he later takes his habitual residence abroad, with the transfer of his habitual residence to Abroad."

The legal validity of the regulation was significant in an inheritance case. Its solution depended on whether the expatriation of a Jewish German citizen on the basis of this provision had been legal. The Federal Constitutional Court answered this question in the negative with reference to the ideas of Radbruch's formula as follows:

"1. National Socialist 'legal' regulations can be denied validity as law if they contradict fundamental principles of justice so clearly that the judge who wanted to apply them or recognize their legal consequences would pronounce injustice instead of right. […]

2. In the 11th ordinance on the Reich Citizenship Law of November 25, 1941 ( RGBl. I p. 772) the contradiction to justice has reached such an unbearable level that it must be considered null and void from the start . "

Even a consistent application of Radbruch's formula leads to results that may not be tenable from the point of view of justice. This is also recognized by the Federal Constitutional Court with reference to the Basic Legislature : The complete denial of the validity of a legal norm (such as the “expatriation” laws) - the so-called “sociological validity” (so called by the Federal Constitutional Court) Legal norm completely off. It is about the finding that rules that are not to be observed in the sense of Radbruch's formula, if not acceptable, have "actually" or "sociologically" existing consequences. In the case of “ expatriations ”, this means in concrete terms that those affected by these expatriations have actually been refused recognition of their citizenship, which cannot be undone; and that many of them have come to terms with the “fact” of their “expatriation” in one way or another, for example by taking on another citizenship. This must be taken into account and the “ status quo ante ” cannot simply be restored without further ado, by withdrawing all (legal) consequences of the “expatriation” rules . So there is nothing left but to take into account in a certain sense those rules that are denied legal quality.

Furthermore, the Federal Constitutional Court points out that the injustice of "expatriation", i.e. usually a blatant violation of the will of the fellow citizens concerned, cannot be made good by again disregarding their will by (again) German citizens become (or it is recognized that they continue to be), to a certain extent, the citizenship of a state is forced upon them, which has persecuted them and which they may have turned their backs on for all time. For this reason, too, the consequences of the rule not to be taken into account are to be recognized as "actually" present despite the Radbruch formula.

Wall rifle trials

Radbruch's formula gained renewed relevance after the peaceful revolution in the GDR and the reunification that followed in 1990 as part of the wall rifle trials . This concerned both the criminal liability of former GDR border soldiers who shot GDR citizens fleeing from the GDR to the Federal Republic of Germany while performing their service on the inner-German border , and the criminal liability of their commanders as indirect perpetrators .

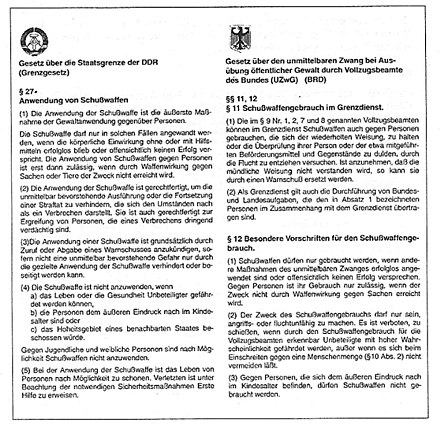

The prevailing view was that the written law of the GDR justified the killing of unarmed refugees in the border area. Both Section 17 (2) (a) of the VoPoG and (since 1982) Section 27 of the GDR Border Act came into question as justification for the border guards. Section 27 (2) sentence 1 of the Border Act had the following wording:

"The use of firearms is justified in order to prevent the imminent execution or continuation of an offense which, under the circumstances, turns out to be a crime."

The Federal Court of Justice assessed the actions of the former border guards and their commanders as unjustified cases of manslaughter according to Section 212 (1) of the Criminal Code . The BGH declared the justification contained in Section 27 (2) sentence 1 of the GDR Border Act to be inapplicable. In addition to aspects of international law, the Federal Court of Justice explicitly invoked the idea of Radbruch's formula in its judgment of March 20, 1995 at the latest: Section 27 (2) of the Border Act violates elementary principles of justice and is therefore irrelevant. In this regard, the Federal Court of Justice pointed out, in its opinion, substantial differences in the content of injustice between the authorization to shoot under Section 27 (2) of the Border Act and various forms of Nazi injustice. As a result, the Federal Court of Justice held Radbruch's formula to be applicable to wall shooter cases as well. The threshold of extreme injustice had also been exceeded in these cases. Consisting of Art. 103 para. 2 Basic Law the following prohibition of retroactive punishment (legal principle to lat .: nulla poena sine lege ) held the Supreme Court for not affected because it did not provide any legitimate expectation on the inviolability of a particular State practice. The Federal Constitutional Court rejected the constitutional complaints lodged against the judgments of the Federal Court of Justice in its decision on the wall riflemen of October 24, 1996. In contrast to the Federal Court of Justice, the Federal Constitutional Court raised the issue of retroactive effects. However, it did not consider Article 103 (2) of the Basic Law to be violated as a result. For cases of extraordinary injustice, an unwritten limitation clause should be built into the otherwise absolutely applicable non-retroactivity clause.

Criticism of the jurisprudence

The case law of the Federal Constitutional Court and the Federal Court of Justice on the Radbruch formula was assessed very differently.

Fundamental misgivings about Radbruch's formula - especially in the context of the wall rifle trials - were also raised by non-positivist critics. These allowed the concept of Radbruch's formula to apply and in particular welcomed its application to certain regulations from the National Socialist era, as had happened in the Federal Constitutional Court's decision on citizenship . However, they faced the case law on the shots at the inner-German border, either in terms of the result or in terms of the reasons for the decisions, from critical to negative. The first form of this - non-positivist - criticism referred to the question, which the Federal Court of Justice answered in the negative, as to whether the different injustice content of Nazi norms such as Section 2 of the 11th Reich Citizenship Ordinance on the one hand and Section 27 (2) of the GDR Border Act on the other hand would make Radbruch's formula applicable Forbid the fall of the wall guards. Both Ralf Dreier - a fundamental proponent of Radbruch's formula - as well as other authors denied that the shots at the inner-German border exceeded the threshold of extreme injustice. In this context, attention was also drawn to the fact that the wording of Section 27 of the GDR Border Act was definitely comparable with the corresponding provisions of Federal German law ( Section 10 (1) sentence 1 UZwG ).

The second form of non-positivist criticism welcomed the case law on the shots at the inner-German border, but criticized the justification given by the case law for this result. Robert Alexy, for example, took the view that Section 27 (2) of the GDR Border Act had crossed the threshold of extreme injustice. He noted, however, that the criminal liability of the border guards who had been influenced accordingly from their youth in the GDR was questionable. An unavoidable mistake in the prohibition , which would have led to the acquittal of the wall gunners, was at least obvious. Steffen Forschner, in turn, attested that the Federal Court of Justice in particular had a fluctuating argumentation: in particular, its first relevant judgment of November 3, 1992 did not make it sufficiently clear to what extent the Federal Court of Justice based its decision to punish the wall protectors on positive international law or on over-positive legal standards in the sense of Radbruch's formula.

Legal philosophical significance and criticism

Radbruch's formula is at the center of the current legal philosophical discussion about the appropriate formulation of the legal term. Specifically, it is about the controversy between the representatives of the right positivist "separation thesis" on the one hand and the non-positivist "connection thesis" on the other. This dispute is based on the question of whether it is appropriate to integrate Radbruch's concept of “unbearable” injustice as an exclusive defining feature in the concept of law.

The “separation thesis” formulates a positivistic legal term. It was or is represented in particular by HLA Hart and - in German-speaking countries - by Norbert Hoerster : The concept of law should be defined in such a way that it contains no moral elements - including no reference to “extreme injustice”. According to the advocates of the separation thesis, all norms that have passed the legislative procedure correctly and are predominantly socially effective are right. In addition to a general epistemological skepticism, the main argument of the supporters of the positivist legal term is the so-called "clarity argument". HLA Hart summed up this argument in its classic formulation as follows:

“For if we agree with Radbruch's view and, with him and the German courts, clothe our protest against reprehensible laws in the assertion that certain norms cannot be right because of their moral untenability, we will bring confusion into one of the strongest, because it is simplest, forms of morality Criticism."

Legal positivists such as Hart and Norbert Hoerster also consider Radbruch's formula to be a hidden circumvention of the non-retroactivity rule . The circumvention of the non-retroactivity rule is seen in the fact that people are subsequently punished for misdemeanors and crimes within the framework of Radbruch's formula, even though their acts were not declared punishable by positive law at the time they were committed. This criticism of the right-wing positivists of Radbruch's formula should not be misunderstood: Hart, too, considered it fundamentally right to punish Nazi criminals retrospectively for their acts. However, he called on the jurisprudence to openly refer to this subsequent punishment as a partial suspension of the non-retroactivity rule. Hart described this disclosure as a requirement of clarity and argumentative honesty.

The advocates of the "connection thesis" (in Germany currently particularly decidedly Robert Alexy and Ralf Dreier), on the other hand, advocate a legal concept that also includes moral elements. They fundamentally recognize the strength of the two main arguments of the legal positivists - the clarity argument and the retroactive argument. Robert Alexy is of the opinion, however, that a legal term supplemented by the content of Radbruch's formula does not have any serious disadvantages in terms of clarity compared to the positivistic legal term. Cases of “extreme injustice”, to which the Radbruch formula alone is based, are clearly recognizable in contrast to “normal injustice”. For this reason, legal security is not endangered if the legal term is supplemented by moral elements in the sense of Radbruch's formula. Alexy does not consider the retroactive argument to be conclusive either. In this regard, he again refers - now with the opposite intention - to the clarity argument: Since extreme injustice is clearly recognizable ( evident ), no one should rely on the apparent legitimation of their actions by extremely unjust laws: It is already at the time of the act for everyone who based on such laws, immediately understandable that he was actually doing an injustice. To reinforce this argument, the following is also put forward: Radbruch's formula does not retrospectively change the legal situation that was objectively applicable at the time of the offense. It merely establishes in a declaratory manner how the legal situation had been objectively presented at an earlier point in time - on the basis of certain principles of material justice. For these reasons, the allegation of hidden retroactive effect is also rejected by the representatives of the connection thesis. Alexy therefore represents the following legal term based on the "connecting thesis":

"The law is a system of norms [...] which consists of the totality of norms that belong to a largely effective constitution and are not extremely unjust."

The legal concept of Radbruch's formula can be mapped in a normative theory of legal validity. This succeeds impressively using a basic norm of natural or rational law, which, in contrast to Hans Kelsen's positivistic basic norm, not only functions as an epistemological or “methodological a priori” of the norm's validity, but as a actually existing sentence of over-positive law. Ralf Dreier develops a "basic norm type Kant-Radbruch", which links the validity of positive law to a two-stage legal ethical condition. On the one hand, the overall system must be "firstly by and large socially effective and secondly, by and large, ethically justified". In Immanuel Kant's sense, this amounts to calling for the establishment of a democratic state constitution. On the other hand, each individual (subordinate) norm of the system must have "firstly a minimum of social effectiveness or effectiveness and, secondly, a minimum of ethical justification or justifiability".

The question remains whether the "basic standard type Kant-Radbruch" is structurally excessive. Björn Schumacher objects that a simpler “Kant-Radbruch basic norm”, which makes the validity of all norms of a legal system dependent solely on the existence of a democratic state constitution, regularly leads to the same result as the “Kant-Radbruch basic norm”. This is based on the ability of the democratic constitutional state to eliminate unethical laws, ordinances, etc. from the legal system by means of specific procedures and institutions. On top of that, as Schumacher emphasizes, laws in constitutional states with a codified part of fundamental rights that are grossly unethical or unbearably unjust are not applicable law, if you will: positivistic, legal concept because they violate higher-ranking constitutional principles.

However, Dreier could defend his "basic norm type Kant-Radbruch" with a pedagogical argument. It is possible that a doctrine of validity with a twofold legal ethical reference protects the democratic constitutional state more effectively from being perverted into a totalitarian unjust state - provided that it is unequivocally propagated by jurisprudence. The decline of the Weimar Republic took place in the opposite direction. The creeping erosion of democratic principles before 1933, which was also based on the disdain for the guiding principles of state ethics in jurisprudence at the time, became a considerable catalyst for Adolf Hitler's “ seizure of power ”.

In his criticism of Radbruch's formula, HLA Hart went beyond the criticism expressed in the context of the systematic dispute about the separation thesis or the connection thesis. He had a human understanding of what Radbruch believed was the turnaround from positivism to nonpositivism and attributed this to personal impressions of Radbruch during the Third Reich . However, he considered Radbruch's formula to be untenable in terms of legal philosophy. It contained no serious intellectual argumentation, but only a passionate warning that was not based on detailed discussions.

See also

literature

Relevant publications by Radbruch

- Philosophy of Law III . In: Arthur Kaufmann (Ed.): Gustav Radbruch Complete Edition . tape 3 . Heidelberg 1990, ISBN 3-8114-4389-5 .

- Statutory injustice and supra-statutory law . In: Süddeutsche Juristerneitung . 1946, p. 105-108 , JSTOR : 20800812 (also in DigiZeitschriften : GDZPPN001325574 .).

- Five minutes of legal philosophy (1945) . In: Ralf Dreier, Stanley L. Paulson (ed.): Gustav Radbruch, Philosophy of Law (study edition) . 2nd Edition. Heidelberg 2011, p. 209 f .

- Legal philosophy . In: Ralf Dreier, Stanley L. Paulson (Ed.): Gustav Radbruch, Philosophy of Law (study edition) . 3. Edition. Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8114-5349-4 .

- Preschool of Legal Philosophy . 2nd Edition. Goettingen 1959.

Secondary literature

Explicitly on Radbruch's formula

- Björn Schumacher: Reception and criticism of the Radbruch formula . Göttingen 1985.

- Stanley Paulson, Ralf Dreier: Introduction to Radbruch's legal philosophy . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . 2nd Edition. Heidelberg 2011, p. 235-250 .

- Robert Alexy: Wall shooters. On the relationship between law, morals and criminal liability . Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-525-86282-2 .

- Frank Saliger: Radbruch formula and the rule of law . Heidelberg 1995, ISBN 3-8114-6295-4 .

- Robert Alexy: The decision of the Federal Constitutional Court on the killings on the inner-German border of October 24, 1996 . Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-525-86293-8 .

- Horst Dreier: Gustav Radbruch and the Wall Riflemen . Legal journal 1997, p. 421 ff .

- Knut Seidel: Legal Philosophical Aspects of the “Wall Protecting” Processes . Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-09748-3 .

- Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Tübingen 2003 ( Online [PDF; 333 kB ] dissertation).

- Hidehiko Adachi: The Radbruch formula: an investigation of Gustav Radbruch's philosophy of law . Baden-Baden 2006, ISBN 3-8329-2028-5 .

- Hans Vest: Justice for crimes against humanity? National prosecution of state system crimes with the help of Radbruch's formula . Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-16-149103-3 .

To the separation thesis / connection thesis

- HLA Hart: Positivism and the separation of law and morality . In: HLA Hart: Law and Morals. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, ISBN 3-525-33311-0 , p. 14–57 , urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .

- Robert Alexy: Concept and validity of the law . Freiburg and Munich 1992, ISBN 3-495-48063-3 .

- Matthias Kaufmann: Philosophy of Law . Munich 1996, ISBN 3-495-47478-1 .

- Norbert Hoerster: What is law? Basic questions of legal philosophy . Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54147-X .

Web links

- Gustav Radbruch: Legal injustice and supra-legal right (excerpt) . (PDF; 50 kB)

- Gustav Radbruch: 5 minutes of legal philosophy . (PDF; 13 kB)

- Information on Radbruch's formula . Institute for Legal Informatics at Saarland University ; with further links

Individual evidence

-

↑ These authors include:

- Stanley Paulson , Ralf Dreier : Introduction to Radbruch's legal philosophy . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law . Study edition. Heidelberg 1999, p. 245 .

- Hans Vest : Justice for crimes against humanity ? National prosecution of state system crimes using the Radbruch formula . Tübingen 2006, p. 18 .

- ↑ By means of these two characteristics Robert defines Alexy : Concept and validity of law . Freiburg / Munich 1992, p. 29 . the right positivist legal term . Alexy also distinguishes primarily setting-oriented and primarily effectiveness-oriented positivist legal terms, but explains in detail that all legal positivists (to varying degrees) include both defining features in their definition of the legal term.

- ↑ In the complete edition you can find the article in volume 3, page 83 (90).

- ↑ Richard Lange: The Supreme Court Jurisprudence for the British Zone on Crimes against Humanity . In: SJZ 1948 . 1948, p. 655 ff .

- ↑ Retrodigital copies at: DigiZeitschriften and JSTOR .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Preschool of the Philosophy of Law - transcript of a lecture. Edited by Harald Schubert and Joachim Stoltzenburg. Scherer Verlag, Heidelberg 1947. In the foreword Radbruch writes: Two listeners to my legal philosophy lecture […] asked me to authorize them to reproduce the transcript of this lecture. [...] I have revised the text, but given it the character of a lecture postscript. Radbruch died a short time after he wrote this foreword, so it was only published posthumously.

- ^ A b Gustav Radbruch: Preschool of Legal Philosophy . 2nd Edition. Göttingen 1959, p. 33 .

- ↑ Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Tübingen 2003, p. 13 ( Online [PDF; 333 kB ] dissertation). Cf. Norbert Hoerster: What is law? Basic questions of legal philosophy . Munich 2006, p. 80 .

- ↑ On the concept of prima-facie precedence see Robert Alexy: Theory of Fundamental Rights . 2nd Edition. Frankfurt am Main 1994, p. 87 ff . (with further references to specialist philosophical literature). According to this, prima facie reasons are - in contrast to definitive reasons - those that can be eliminated by opposing reasons.

- ↑ So z. B. from Robert Alexy: Wall protection. On the relationship between law, morals and criminal liability . Hamburg 1993, p. 4 .

- ^ A b Stanley Paulson, Ralf Dreier: Introduction to the legal philosophy of Radbruch . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . Heidelberg 1999, p. 245 .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Preschool of Legal Philosophy . 2nd Edition. Göttingen 1959, p. 34 .

- ↑ For example, Robert Alexy does this for "extremely unjust" law: Robert Alexy: Concept and validity of law . Freiburg and Munich 1992, p. 201 .

- ↑ Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Tübingen 2003, p. 10 f . ( online [PDF; 333 kB ] Dissertation, with further evidence).

- ↑ Knut Seidel: Legal Philosophical Aspects of the "Wall Protecting" Processes . Berlin 1999, p. 176 .

- ↑ Cf. instead of many Robert Alexy: Mauerschützen. On the relationship between law, morals and criminal liability . Hamburg 1993, p. 22 .

- ↑ Radbruch did not give an exhaustive statement on these epistemological questions after 1945. Previously (most recently explicitly in 1932) he had denied the possibility of objectively distinguishing between right and wrong on the basis of his neo-Kantian value relativism. See also the following parts of the article, in particular the section Position of the formula within Gustav Radbruch's legal philosophy .

- ↑ HLA Hart: Positivism and the separation of law and morality . In: HLA Hart (Ed.): Law and Moral. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, p. 51 ff ., urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: 5 minutes of legal philosophy . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . 1st edition. Heidelberg 1999, p. 209 f., 210 .

- ↑ Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Tübingen 2003, p. 14th f . ( online [PDF; 333 kB ]).

- ↑ See also the essay by Stanley Paulson and Ralf Dreier: Introduction to the legal philosophy of Radbruch , in: Gustav Radbruch: Rechtsphilosophie . Study edition, Heidelberg 1999, pp. 235-250.

- ↑ The assumption of a fundamental epistemological gap between being and ought was first advocated by David Hume . She also played an important role in the work of Immanuel Kant and the Neo-Kantians . Radbruch was a supporter of the Heidelberg direction of Neo-Kantianism, which included Wilhelm Windelband , Heinrich Rickert and Emil Lask , among others . The second edition of his legal philosophy from 1932 was explicitly committed to the philosophical tradition of Heidelberg Neo-Kantianism. Cf. on this Gustav Radbruch: Legal Philosophy . 2nd Edition. 1932, p. 1 ff . and Stanley Paulson, Ralf Dreier: Introduction to Radbruch's legal philosophy . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . Heidelberg 1999, p. 235-250, 236 .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law . 2nd Edition. 1932, p. 54 .

- ↑ On the debate, see above all Knut Seidel: Legal Philosophical Aspects of the “Wall Protecting” Processes . Berlin 1999, p. 159 ff .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Preschool of Legal Philosophy . 2nd Edition. Göttingen 1959, p. 29 .

- ^ Stanley Paulson, Ralf Dreier: Introduction to the legal philosophy of Radbruch . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . Heidelberg 1999, p. 248 . and Hidehiko Adachi: The Radbruch Formula: An Investigation of Gustav Radbruch's Philosophy of Law . Baden-Baden 2006, p. 93 ff .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . 2nd Edition. Heidelberg 2003, p. 35 .

- ^ Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . 2nd Edition. Heidelberg 2003, p. 85 : "We despise the pastor who preaches against his convictions, but we honor the judge who does not allow himself to be deterred in his legal compliance by his reluctant sense of justice."

- ↑ See the description by Knut Seidel: Legal Philosophical Aspects of the "Wall Protecting" Processes . Berlin 1999.

- ↑ Positivism and the separation of law and morality . In: HLA Hart: Law and Morals. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, p. 40 , urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .

- ↑ Lon Fuller: American Legal Philosophy at Mid-Century . In: Journal of Legal Education 6, 1954 . S. 457-485 .

- ↑ For example HLA Hart in his essay The Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morality . In: HLA Hart: Law and Morals. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, p. 39 ff ., urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .

- ↑ See instead of many Stanley Paulson, Ralf Dreier: Introduction to Radbruch's Philosophy of Law . In: Gustav Radbruch: Philosophy of Law, study edition . Heidelberg 1999, p. 248 .

- ↑ Augustin: De libero arbitrio (German: The Free Will ), I 5, page 11.

- ↑ Cf. only Robert Alexy: Concept and validity of law . Freiburg and Munich 1992.

- ↑ Arthur Kaufmann: Philosophy of Law . 2nd Edition. Munich 1997, p. 40 ff .

- ↑ Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Tübingen 2003, p. 14 ( online [PDF; 333 kB ]).

- ↑ Hans Vest criticizes this lack of differentiation: Justice for crimes against humanity? National prosecution of state system crimes with the help of Radbruch's formula . Tübingen 2006, p. 21 .

- ↑ III ZR 168/50, BGHZ 3, 94 ( shooting of a deserter by members of the Volkssturm in the last days of World War II).

- ↑ a b BVerfG, decision of February 14, 1968, Az. 2 BvR 557/62, BVerfGE 23, 98 - Expatriation I.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of April 15, 1980, Az. 2 BvR 842/77, BVerfGE 54, 53 - Expatriation II.

- ↑ Monika Frommel spoke of a “surprising topicality”: Monika Frommel: The Wall Rifle Trials - an unexpected topicality of Radbruch's formula . In: Haft et al. (Ed.): Festschrift for Arthur Kaufmann on his 70th birthday . Heidelberg 1993, p. 81 ff .

- ↑ According to § 213 Abs. 3 Satz 1 DDR-StGB i. d. F. of June 28, 1979, the so-called unlawful border crossing in serious cases was considered a crime. A serious case was already accepted by the GDR Supreme Court if, for example, a ladder was used to cross the border without permission. Compare with this Robert Alexy: Mauerschützen. On the relationship between law, morality and criminal liability . Hamburg 1993, p. 11 .

- ↑ Relevant decisions: Judgment of November 3, 1992 - 5 StR 370/92 , BGHSt 39, 1 ( criminal liability for the use of firearms at the inner-German border); Judgment of March 20, 1995 - 5 StR 111/94 , BGHSt 41, 101 ( acts of killing at the inner-German border )

- ↑ Judgment of March 20, 1995 - 5 StR 111/94 (Section D. II. 3. a) aa)), BGHSt 41, 101 ( acts of killing on the inner-German border )

- ↑ Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Tübingen 2003, p. 99 ( uni-tuebingen.de [PDF; 333 kB ]).

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of October 24, 1996, Az. 2 BvR 1851/94, BVerfGE 95, 96 - Wall protection.

- ↑ See also Robert Alexy: The decision of the Federal Constitutional Court on the killings on the inner-German border of October 24, 1996 . Hamburg 1997, p. 18th ff .

- ↑ Ralf Dreier: Legal coming to terms with the past . Baden-Baden 1995, p. 33 .

- ↑ Frank Lucien Lorenz: “Legal Validity”, GDR “History” and Appropriateness of Punishment . In: JZ 1994 . 1994, p. 388 ff . and Jörg Arnold , Martin Kühl: Forum: Problems of the criminal liability of "wall shooters" . In: JuS 1992 . 1992, p. 911 f .

- ↑ Robert Alexy: Wall protection. On the relationship between law, morality and criminal liability . Hamburg 1993, p. 36 ff .

- ↑ BGH, judgment of November 3, 1992 - 5 StR 370/92, BGHSt 39, 1.

- ↑ Steffen Forschner: The Radbruch formula in the supreme court “wall rifle judgments” . Online dissertation 2003, p. 62 ( online [PDF; 333 kB ]).

- ↑ The author of the separation thesis is considered to be John Austin : The Province of Jurisprudence Determined . (1832). Cambridge 1985, pp. 184 ff .; It was shaped by HLA Hart: Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morals . In: Harvard Law Review 71 (1958), pp. 593-629 .; See also: Florian Rödl: On the criticism of the right-wing positivist conception of human rights . In: Margit Wasmaier-Sailer, Matthias Hoesch (ed.): The justification of human rights. Controversies in the area of tension between positive law, natural law and law of reason , Perspektiven der Ethik 11, Mohr Siebeck 2017, ISBN 978-3-16-154057-8 . Pp. 29-42 (33).

- ↑ Armin Engländer : Discourse as a legal source ?: on the critique of the discourse theory of law . In: The unit of social sciences, 125. Mohr Siebeck 2002, p. 89 ff .; Robert Alexy : Concept and validity of law , Alber study edition, Verlag Karl Alber, Freiburg / Munich, 3rd edition 2011, ISBN 978-3-495-48063-2 , p. 83 ff.

- ↑ The Austrian legal positivist Hans Kelsen advocated a very similar legal term, although he did not take an active part in the debate about Radbruch's formula.

- ↑ HLA Hart and Norbert Hoerster, however, consider it possible to defend the position of legal positivism even without reference to the epistemological problem of the intersubjective definition of “extreme injustice”.

- ↑ HLA Hart: Positivism and the separation of law and morality . In: HLA Hart: Law and Morals. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, p. 14-57, 45 f ., urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .

- ↑ HLA Hart: Positivism and the separation of law and morality . In: HLA Hart: Law and Morals. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, p. 44 , urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .

- ↑ a b Robert Alexy: Concept and validity of the law . Freiburg and Munich 1992, p. 105 .

- ↑ Cf. instead of many Robert Alexy: Mauerschützen. On the relationship between law, morals and criminal liability . Hamburg 1993, p. 33 .

- ↑ Robert Alexy: Concept and validity of the law . Freiburg and Munich 1992, p. 106 .

- ↑ Ralf Dreier: Law - Morality - Ideology . P. 197 f.

- ↑ Björn Schumacher: Reception and criticism of the Radbruch formula , p. 67 f.

- ↑ See also Martin Kriele: State Philosophical Lessons from National Socialism , in: Legal Philosophy and National Socialism (ARSP, supplement 18, 1983), pp. 210–222.

- ↑ HLA Hart: Positivism and the separation of law and morality . In: Law and Morals. Three essays . Göttingen 1971, p. 45 , urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb00048107-7 .