Reflex arc (physiology)

In physiology, the reflex arc is the shortest connection between receptor and effector via the nerve cells of a specific neuronal excitation circuit. In the simplest case, the connection from the afferent to the efferent neuron takes place on the spinal level via a synapse in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. This type of reflex is therefore more precisely referred to as a simple monosynaptic reflex arc .

Proprioception and control loop

The term reflex arc and the associated physiological neuron theory is based on the concept of the technical control loop and corresponding input / output systems. In contrast to the purely physiological concept of the reflex, the concept of the reflex arc emphasizes the biological principle of organization in topological terms . The exact knowledge of topographical conditions enables an exact topical diagnosis . It is facilitated by the fact that the entire monosynaptic reflex arch is at the same level of the spinal cord, the precise knowledge of which is therefore also clinically important. The examination of the reflexes is part of the standard neurological examination.

The problem of topical diagnostics and the associated theory of localization also sounds like the concept of proprioception or the principle of self-control or self-regulation . Even if only a small part of the impulses of proprioception reach consciousness , and thus the cerebral cortex, the concept of the reflex arc must not be understood exclusively in the sense of a simple mechanical automatism. This would be an inadmissible simplification that does not do justice to the nature of the living organism. A single nerve cell receives excitations not only from one or two neurons, but from numerous, even up to thousands, of neurons. This also applies to the motor anterior horn cells in the spinal cord, cf. the following section Elements of the reflex arc . So z. B. the reflex arc promoting or inhibiting central influences through the pyramidal trajectories that switch on at the peripheral motor neuron in the reflex arc. They act physiologically in self-reflection inhibit a reflex response, however, promoting in damage to the pyramidal tract system, see. Pyramid orbit sign .

Of the multitude of actual reflex arcs, the monosynaptic self- reflex is mainly shown here.

Elements of the reflex arc

According to the principle of a control loop, a distinction is made:

- on the input side (picture " control circuit ", symbol w) the afferent leg of the arch (blue in picture " cross section "); Origin = sensor or feeler in technology = receptor ( muscle spindle ) in biology; Transmission of the stimulus through a unipolar nerve cell in the spinal ganglion

- on the output side (picture " control circuit ", symbol y) the efferent leg of the arch (red in picture " cross section "); Transmission of the stimulus response through motor anterior horn cells; Goal = actor or effector in technology = effector (physiology) or active organ in physiology (muscle or gland)

Afferents in simple ( monosynaptic ) reflexes have their origin in sensory organs or other sensory or sensory receptors in muscles (receptor: muscle spindles ), tendons or in the skin ( sense of touch ). The transmission of the afferent impulses to the spinal cord takes place via sensitive nerve cells (mostly Aα fibers according to Erlanger Gasser or Ia fibers / Ib and II fibers according to Lloyd / Hunt). With regard to the neuronal cell type, these are pseudounipolar nerve cells, the cell body of which is located in the spinal ganglion (picture " cross section ", number 13: spinal ganglion). This is located within the spinal canal, but does not belong to the central, but to the peripheral nervous system, see the definition of the polysynaptic reflex .

Efferents have their destination in muscles or glands. The forwarding of the efferent impulses from the spinal cord via motor nerves ( motor neurons ), whose cell bodies in the region of the gray matter of the spinal cord in the motor anterior horn (Figure " cross-section ", paragraph 1: ventral horn) is located. The motoaxon leading to the effector (muscle) belongs to the Aα-fibers (short: α-motoneuron) with regard to the conduction velocity. The muscle spindles are supplied by different types of Aγ fibers (γ motor neurons for short).

Physiological components

The reflex response of a living being in the sense of the reflex arc consists of the following individual functional facts:

- Registration of an adequate (usually referred to as "triggering", mechanically possibly also interpreted in this way) stimulus or stimulus to which this living being reacts on its own,

- Forwarding of the resulting neural activation or "excitation" of the respective sensory nerves to their specific processing center (reflex center) in the rope ladder nervous system in lower animals or in the spinal cord in more developed animals,

- Synaptic transfer of the incoming excitation to anatomically fixed motor nerves connected to the afferents , via which the respective reflex response comes about or is "set in motion",

- Forwarding the activation of the respective motor nerves to the muscles or glands (as effectors), their interaction with the reflex response (engl. Response ) leads and

- Activation of these effectors, through which the reflex (in the case of muscles as an effector or as a reflex physical movement) comes about that defines the respective reflex.

More terms

Occasionally one also speaks of a reflex circuit, although reflexive relationships of a more complex nature and nested control loops can also be meant. The time from the effect of the stimulus to the motor response is known as the reflex time .

Mono- and polysynaptic reflexes

Reflex reactions that occur via monosynaptic reflex arcs ( self-reflexes ) are the fastest organismic reflexes, as they only run over a single synapse in the spinal cord. As spinal cord reflexes , their course cannot be deliberately influenced once they have started; conscious influencing can only be achieved indirectly via stimulus control. These monosynaptic reflexes are also called self-reflexes because receptor and effector are in the same organ.

Examples of self-reflexes:

- Patellar tendon reflex = PSR

- Achilles tendon reflex = ASR

- Critical note : The term “tendon reflex” is pragmatic because it describes the type and manner of release, namely by striking the tendon with the help of the reflex hammer. Unfortunately, this naming appears to be non-physiological, since “tendon reflexes” are always “muscle stretching reflexes”. Therefore, instead of the practical terms PSR and ASR u. a. the physiologically correct names quadriceps reflex for PSR and triceps surae reflex for ASR preferred. For further critical remarks on the classical pragmatic-experimental reflex theory see Chap. Reflex arc as a model .

In the case of the polysynaptic reflexes, several central neurons are connected in series. Receptor and effector are usually spatially separated, so that they are also referred to as external reflexes .

Examples of external reflexes:

- When coughing , the stimulus is absorbed by foreign bodies in the throat (receptor). The respiratory muscles (effector) provide the stimulus response.

- In the case of the corneal reflex , the cornea of the eye (receptor) is touched, the stimulus response comes from the eyelid muscles (effector).

Reflex arc as a model

The reflex arc as a physiological model is of great importance for understanding the functioning of the entire nervous system. This already applies to the conceptual understanding of the reflex arc given by definition (in the opening credits) as a special case of the far more complex functioning of neuronal excitation circuits . The vegetative and animal nervous systems operate according to this principle, but as such subunits only represent elements within the entire nervous system. Based on the function of neural networks , the activities of the higher centers of the CNS can be understood more fundamentally. B. also the distinction between association cortex and sensorimotor cortex . Projection centers can e.g. As analogous to the spinal centers as part of a " psychic reflex arc be understood" (Jaspers), see also the theory of spinal irritation of Wilhelm Griesinger . The function of the association cortex can be understood in analogy to the polysynaptic reflex .

This model character thus also extends to the understanding of psychological conditions including mental illnesses and disorders. The latter can e.g. Sometimes understood as a failure of homeostasis or as a failure of unconscious self-regulation . Even the modern term of a mental disorder shows such parallels to technical terms from control engineering such as the disturbance variable . Biological disturbances correspond to dealing with the changing situations in the environment. In this way, information can also be obtained about physical control mechanisms in mental illness. This point of view primarily concerns questions of psychophysical correlation .

The description of the conditioned reflex by the Russian scientist Ivan Petrowitsch Pawlow (1849–1936) represents a first step in this direction in the history of science. Here, phenomena of perception and learning were included in the theory of reflex. The example of Pavlov also shows the socio-political (materialistic) backgrounds of his theory of reflexes, which his opponents sometimes call "reflex mythology". Pavlov tried, with his predilection for physiology , to ban all psychological terms from his and the vocabulary of his colleagues. He received the Nobel Prize in 1904 for his work on the activity of the digestive glands. Modern representations of this historical phenomenon, which also caused movement in the West German past, show the different interpretations of cybernetic issues. The introduction of cybernetic terminology can lead to an enrichment of the description of mental disorders, which is not possible in the language of classical physics. Terms of control technology such as B. "Taking into service" clarify integrative functions of the CNS (among other things also comparable with factors of social influence and corresponding " taking into service") and the modular structure of the nervous system, which is comparable with certain technical solutions . The term modules is also used in the neurosciences . The more complex these tasks are, the more likely they can be assessed as psychological functions, which also often happens in practice when one cannot explain certain reactions of a person.

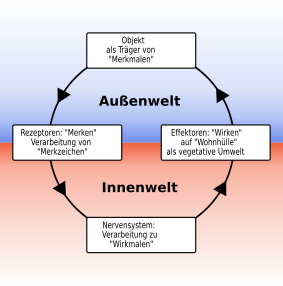

Functional circuit according to Jakob von Uexküll as a control circuit on the vegetative level

Psychophysical correlation as a control loop on the animal level

The classic theory of reflexes by Pavlov, as it is also the basis of behaviorism, is based on experimental observation in the laboratory, see Experimental Psychology . John B. Watson (1878–1958) laid down the model for this new science in 1913, which later also proved its worth as a behavioral science or behavioral analysis . First of all, the externally observable physiological processes were examined, see blue area in the picture “ Functional circuit ” (“outside world”). The physical influences affecting the biological system ("red area") afferent or receptorily from the outside were named as stimulus, the efferent or effectoric stimulus responses emanating from the biological system as reactions (English response or reaction) . The stimulus was given a determining, causal and superficial meaning. However, these ideas, which are primarily determined by the machine paradigm, required a revision, since the biological system also has its own effectiveness and role in these processes. The so-called S / R linkage (stimulus / response model) in biological organisms must therefore be differentiated from purely physical processes according to the cause-effect mechanism , even though it suggests such an interpretation. In the case of the autonomous (so-called "primarily active") processes of biological systems, the polysynaptic connections in reflex processes must also be taken into account, in particular the influences of the vegetative and animal nervous system and their readiness to react. In addition to the innate reflex processes, not only learned influences must be taken into account ( conditioning ), the general development and maturation of the biological system under investigation also plays a role, see the blue area in the picture " Functional circle " ("inner world" - vegetative NS) and the In picture “ Psychophysical Correlation ” (“psychic system” - animal NS) further subdivided this inner world into a somatic and psychological area. The “inner world” of the organism in the picture “ functional circuit ” corresponds to both the “somatic system” and the “psychic system” in the picture “ psychophysical correlation ” cf. also the provisional auxiliary construction of the black box . This "box" was named "black box" because the factors of the inner workings should be excluded for methodological reasons. As an example of the effectiveness of the inner world factors (the negative epitome of the “black box”) the Babinski reflex could be mentioned here. Its appearance is tied to the function of central, well-developed pathways. In the mature adult it is usually absent, in the child it is physiological up to the age of 2.

An early critique of the behaviorist reflex arc theory can be found in the neurologist and gestalt theorist Kurt Goldstein . Through his work with brain-damaged soldiers from the First World War , he may come. a. to the result that there are no isolated stimulus-reaction processes in the organism, but that the organism always reacts as a whole.

Kurt Goldstein's work clearly influences the development of Gestalt therapy . Fritz Perls and Laura Perls , the founders of Gestalt therapy, refer directly to Goldstein.

The model character of the reflex arc and its extensive clarification based on bionic examples leave many questions unanswered. Even if the similarity between the central nervous system and the telephone exchange is illustrated by the analogy between the polysynaptic reflex arc and telephone communication in everyday comparisons, the question of communication in plants is an unconsidered and completely different phenomenon. It is well known that plants do not have a nervous system. However, they often have to cope with similar biological tasks as animals and humans. The reflex arc can thus only z. T. serve as an overarching model in biology. For the plant kingdom, for example, completely different conditions apply here.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Friedrich Wilhelm Bronisch: The reflexes . Thieme, Stuttgart 1979; (a) to “reflex arc definition of terms”, p. 3; (b) Re. “Criticism of the reflex designation based solely on the clinical method of its triggering” (criticism of pragmatism ), p. 5; (c) to Stw. “Babinski-Reflex” p. 71 f.

- ↑ simple monosynaptic reflex arc . In: Peter Duus: Neurological-topical diagnostics. Anatomy, physiology, clinic . 5th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-13-535805-4 , p. 11.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Gadamer : About the concealment of health . (Library Suhrkamp, Volume 1135). Frankfurt am Main 1993; on “self-movement” and “heauto kinoun” (Aristotle): chap. Life and Soul, p. 179.

- ↑ a b c d Thure von Uexküll : Basic questions of psychosomatic medicine. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek near Hamburg 1963; (a) Re. "Self-regulation": Chap. Self-regulation and control loop, p. 251 ff .; (b) Re. “Systematic examples for biological disturbance variables ”, p. 262 f .; (c) to Stw. “Reflexmythologie”, p. 165 ff .; (d) to Stw. “Definition of the psychological and complexity of controlled processes” (transferring the concept of “psyche” to the technical model of reference variable switching ), p. 261 f.

- ↑ a b Robert F. Schmidt (Ed.): Outline of Neurophysiology. 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin 1979, ISBN 3-540-07827-4 ; (a) Regarding the terms “Polysynaptic reflex” and “External reflex”, page 126, the like. Regarding the terms “monosynaptic stretch reflex” and “Eigenreflex”, p. 123; (b) Re. “Association cortex”, p. 282.

- ↑ Karl Jaspers : General Psychopathology. 9th edition. Springer, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-540-03340-8 ; Re. “Psychic reflex arc”: Part 1: The individual facts of mental life, Chapter 2: The objective achievements of mental life (achievement psychology) b) The basic neurological scheme of the reflex arc and the basic psychological scheme of task and achievement, pp. 130 ff .

- ↑ Manfred Spitzer : Spirit on the Net. Models for learning, thinking and acting. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-8274-0109-7 ; Re. "Multi-layer networks": Chap. 6. Intermediate layers, p. 125 ff.

- ↑ Homeostasis . In: Stavros Mentzos : Neurotic Conflict Processing; Introduction to the psychoanalytic theory of neuroses, taking into account more recent perspectives. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-596-42239-6 , pp. 53, 187.

- ↑ Homeostasis . In: Stavros Mentzos: Psychodynamic Models in Psychiatry. 2nd Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1992, ISBN 3-525-45727-8 , p. 101.

- ^ Pavlov, Ivan Petrovich . In: Wilhelm Karl Arnold u. a. (Ed.): Lexicon of Psychology . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1996, ISBN 3-86047-508-8 , column 1562 f.

- ↑ Cybernetics and Cultural History . In: Philipp Aumann: Mode and Method. Cybernetics in the Federal Republic of Germany. Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-8353-0449-9 ; review

- ↑ Control technology and psyche . In: Karl Steinbuch : Automat und Mensch. Cybernetic facts and hypotheses. 3. Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 1965, pp. 7, 9, 12, 149, 281, 350, 395, 397, 401.

- ↑ John B. Watson : Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It. In: Psychological Review , 20, 1913, pp. 158-177, psychclassics.yorku.ca - also contained in: John B. Watson: Behaviorismus . Cologne 1968 and Frankfurt am Main 1976

- ↑ Ludwig von Bertalanffy : General System Theory . George Braziller, New York 1968.

- ↑ Peter R. Hofstätter (Ed.): Psychology. The Fischer Lexicon . Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1972, ISBN 3-436-01159-2 ; to Stw. “Conditional Reflex”, p. 62 ff .; to Stw. "Model of a mechanical apparatus" ( machine paradigm ), p. 70 f.

- ↑ Thure von Uexküll u. a. (Ed.): Psychosomatic Medicine. 3. Edition. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-541-08843-5 ; Re. “The need for revision of the classical reflex theory”: Chap. 1.3.1 The emergent properties of the biological system level, p. 10 f.

- ↑ K. Goldstein: The structure of the organism. The Hague 1934, p. 45 ff.

- ↑ see a. FS Perls: The I, the hunger and the aggression. 1946, Stuttgart 1969, p. 59 ff.

- ↑ Volker doctor : Smart plants. How they lure and lie, warn and defend themselves and get help in case of danger . Riemann, 2009, ISBN 978-3-570-01026-6 ; Audio file of the author's book review on February 28, 2010