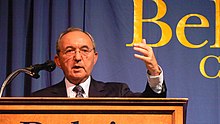

Richard Goldstone

Richard J. Goldstone (born October 26, 1938 ) is a South African lawyer, international lawyer and former UN chief prosecutor. As a lawyer, Goldstone was chairman of the Commission of Inquiry regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation, or Goldstone Commission for short , from 1991 to 1994 and a member of the Constitutional Court of South Africa from 1994 to 2003 . He is also a professor at New York University School of Law and Fordham University School of Law.

Life

Goldstone graduated from Witwatersrand University with an LL.B degree in 1962. He then worked as a lawyer in the Johannesburg Bar Association. In 1976 Goldstone became Senior Counsel and in 1980 Judge of the Transvaal Supreme Court .

His appointment as a judge in 1980 sparked controversy. The appointment of the well-known opponent of apartheid Goldstone, who would nevertheless have to judge according to the apartheid laws and thus apparently could not change much, was used by the South African government ( National Party ) as an advertisement for their alleged openness. On the advice of other lawyers critical of apartheid, Goldstone, who described this as a "moral dilemma ", decided to accept the office anyway. Accordingly, Goldstone judged z. For example, the fact that black women are not allowed to be evicted from their homes in white suburbs without a substitute for housing, on the other hand, according to the law, allowed a 13-year-old student to be sentenced to prison for missing out on school. In 1986 he became the first South African judge to force the release of a political prisoner captured by the government's state of emergency .

According to the Goldstone report (see below), in 2010 the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth published articles according to which Goldstone, as a judge in South Africa, sentenced a total of 28 death sentences and sentenced four defendants to whips, and wrote that he did not have the right to control Israeli politics to judge. Goldstone dismissed this as a lie that he had only given two death sentences against murderers where the law made this punishment mandatory. When later a judge at the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court with appropriate powers he had stopped further executions of death sentences. He pointed out that he was viewed as a judge in South Africa after the end of apartheid and that there were no such serious allegations there.

In 1989 he was a judge at the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court. Between 1991 and 1994 Goldstone was chairman of the Commission of Inquiry regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation , the so-called "Goldstone Commission". In this role he managed to uncover several crimes committed by South African secret service structures. The main investigations into this were carried out in 1992 and 1993. The success of this commission was largely due to the strongly legalistic way of working of Goldstone, according to which only facts that were completely proven beyond doubt were included in its reporting. At first there were failures, for example the investigation into the Boipatong massacre (June 1992). As a consequence of this result, he called for his own team of investigators, which he was also granted. Among them were experienced criminologists from abroad, as he trusted the South African police less and less. Goldstone succeeded on November 11, 1992 in a raid in a prestigious suburb of Pretoria , with the headquarters of a special unit of the military intelligence, whose members had been involved in defamation and corruption actions ( Project Echoes ) against ANC leaders. At least 48 officers are said to have been involved in this secret project, some of whom used to work in the CCB . These and other revelations came during a state visit by Willem de Klerk to Great Britain . He initially questioned the information provided by the commission publicly, but had it checked by General Pierre Steyn, then Chief of Staff of the Air Force , who confirmed it in an internal report after a maximum of four weeks. Some officers were dismissed, but there were no consequences for the management of the Military Intelligence Service .

He achieved an even more comprehensive educational success in 1994 when he cleared up the extensive involvement of employees of the military and security apparatus in a destabilization campaign aimed at preventing the upcoming democratic elections and political change in the country. Although there were no convictions, plenty of information about previously secret units of the Vlakplaas and their diffuse successor structures from 1990 onwards became known. These unmanageable networks of violent security units were referred to as Third Force (German: "third force"). It emerged that large amounts of automatic weapons and ammunition from the former bush war in the independence process of Namibia were collected and distributed to Inkatha forces so that they could use terrorist measures against politically competing ANC groups in KwaZulu and the province of Natal . From December 1993 onwards, Goldstone was able to uncover some incidents from 1986 about the training of 200 Inkatha members by the South African military intelligence service to become sabotage and killing squads in a military base in the Caprivi Strip (today northern Namibia). These received weapons from the stocks of Vlakplaas and operated as death squads on the Witwatersrand as well as in the homeland KwaZulu and in Natal.

Goldstone was also chairman of the Standing Advisory Committee of Company Law . Between July 1994 and October 2003 Goldstone was a member of the Constitutional Court of South Africa .

From August 15, 1994 to September 1996, he was Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda . Between August 1999 and December 2001, Goldstone was the chairman of the international, independent commission of inquiry in Kosovo . In 1999 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

On April 3, 2009, Richard Goldstone was tasked by the UN Human Rights Commission with the task of exposing possible human rights crimes during the Israeli military operation Cast Lead in the Gaza Strip . He published his final report on this, the so-called Goldstone Report , in September 2009. It accuses the Israeli army and Hamas of violating international martial law and condemns them. In an April 1, 2011 article in the Washington Post , however, he questioned his report in part. He explained that his report would have been different if he had already known then what he knew today ( If I had known then what I know now, the Goldstone Report would have been a different document. ). The Israeli side was complicit in this, because he was not given the necessary information. The three co-authors of the Goldstone Report, Hina Jilani , Christine Chinkin and Desmond Travers , sharply distanced themselves from Goldstone's reassessment of the incidents. They judge that nothing has changed in the results of the report and suspected that Goldstone's reassessment was the result of political pressure.

Richard Goldstone is married with two children.

Works

- Richard J. Goldstone (Red.): Final report to the Commission of Inquiry regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation by the committee established to inquire into public violence and intimidation at mass demonstrations, marches and picketing . Cape Town? 1993

- Prosecuting was criminals . Occasional paper, no. 10; David Davies Memorial Institute of International Studies, London 1996

- For Humanity: Reflections of a War Crimes Investigator . Yale University Press , New Haven, London 2000

Individual evidence

- ^ A b William A. Schabas: For Humanity: Reflections of a War Crimes Investigator (Book Review) . In: American Journal of International Law . American Journal of International Law 95, No. 3, July 1, 2001, pp. 742-744. ISSN 0002-9300 .

- ^ A b Richard Goldstone: I have no regrets about the Gaza war report , Haaretz , May 6, 2010

- ↑ a b Richard Cape Town Journal; In a Wary Land, the Judge Is Trusted (to a Point) , New York Times , March 8, 1993

- ↑ Goldstone responds to 'death penalty' allegations , The Jewisch Chronicle, May 2010

- ↑ Allister Sparks : Tomorrow is another land. South Africa's secret revolution . Berlin Verlag 1995, ISBN 3-8270-0151-X , pp. 241-242

- ↑ Allister Sparks: Tomorrow is another land. South Africa's secret revolution . 1995, pp. 245-247

- ^ Richard J. Goldstone (ed.): Report to the Commission by the committee appointed to inquire into allegations concerning front companies of the SADF and the training by the SADF of Inkatha supporters at the Caprivi in 1986 . Pretoria 1993 bibliographic record . on www.copac.jisc.ac.uk (English)

- ↑ a b United Nations: Justice Richard Goldstone on www.un.org (English)

- ^ APA : Richard Goldstone leads UN investigation in Gaza. Der Standard , April 3, 2009, accessed April 4, 2009 (German).

- ^ Goldstone Report on the Gaza War , Zeit.de, Sept. 15, 2009

- ↑ UN sample: Israel, Palestinians both guilty of Gaza war crimes ( Memento from September 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), Haaretz , September 15, 2009

- ^ Reconsidering the Goldstone Report on Israel and war crimes , Washington Post, April 1, 2011

- ↑ guardian.co.uk : UN Gaza report co-authors round on Goldstone April 14, 2011

- ↑ Copac: bibliographic evidence . on www.copac.jisc.ac.uk (English)

- ↑ Copac: bibliographic evidence . on www.copac.jisc.ac.uk (English)

- ↑ Copac: bibliographic evidence . on www.copac.jisc.ac.uk (English)

literature

- Norman Finkelstein : Goldstone Recants. OR Books, New York / London 2011, ISBN 1-935928-51-1 .

Web links

- United Nations : Biography of Richard Goldstone

- Letty Cottin Pogrebin: The Un-Jewish Assault on Richard Goldstone Forward , December 29, 2010.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Goldstone, Richard |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Goldstone, Richard J. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | South African lawyer, international lawyer and former UN chief prosecutor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 26, 1938 |