Horse chestnut leaf miner

| Horse chestnut leaf miner | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Horse chestnut leaf miner ( Cameraria ohridella ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Cameraria ohridella | ||||||||||||

| Deschka & Dimić , 1986 |

The horse chestnut leaf miner ( Cameraria ohridella ), also known as the Balkan leaf miner , is a small butterfly from the family of leaf miners (Gracillariidae). The caterpillars and pupae develop almost exclusively in the leaves of the white-flowering common horse chestnut ( Aesculus hippocastanum ). Due to the extremely rapid spread from its area of origin to almost all areas of Europe, it has attracted a great deal of public and journalistic attention.

The horse chestnut leaf miner was first discovered in Macedonia in 1984 near Lake Ohrid . In 1989 it was detected for the first time in Austria (in the area of Linz and Steyr ) (a first mass increase took place here as early as 1990/91). Since then it has been spreading very quickly in Central Europe , both east and west. Their extremely rapid reproduction can be explained by the fact that the species has few natural enemies in Central Europe or that possible predators have not yet opened up this new niche. In the Central European populations, the degree of parasitization is (so far?) Still low.

The area of origin of the species was initially controversial, since most closely related species occur exclusively in North America. In retrospect, however, finds could be proven on a herbarium that had been collected in Greece in 1879. The area of origin are deep gorges and valleys, which are still difficult to access, in Albania, northern Greece and Macedonia , where the common horse chestnut still occurs naturally today.

features

butterfly

The moth has a body length of 2.28 to 3.04 mm (mean 2.65 mm) and a wingspan of 5.92 to 7.5 mm (6.63 mm). The forewings are shiny metallic red, red-brown, chestnut brown or orange-brown. There is a white longitudinal line in the basal field. In the middle and outer field are four whitish, black-framed, mostly interrupted transverse bands. The hind wings are dark gray. The long fringes at the outer end of the hind wings are noticeable, giving the rear end of the butterfly a feather-like appearance. The species has long, black-and-white ringed antennae, which correspond to about 4/5 of the fore wing length. The head has tufts of orange hair. The legs are ringed in black and white. The proboscis is well developed.

egg

The eggs are whitish, flattened, elliptical, and translucent. They are 0.12 to 0.34 mm (mean 0.27) wide and 0.24 to 0.5 mm (mean 0.37) long.

Caterpillar

Development takes place over six, sometimes seven, larval stages: four to five larval stages (L1 to L4 / L5) that eat, and two so-called prepupa or spinning stages (S1, S2) that no longer eat. Of the latter two, the first stage still lives outside the cocoon, the second stage inside a cocoon. The egg caterpillars and the L2 to L4 / L5 are flattened, they have no legs. The mandibles are directed forward, the head capsule is wedge-shaped. There are 13 body segments that are slightly constricted at the sides. Each segment has some setae. There are some brown striae on the back. The body is translucent so that the digestive system and other organs can be seen. In the spinning stages the head is rounded and a spinning gland is formed. The body of the first spinning stage is gray. The second spinning stage has a pale yellow to cream-colored body. Length: up to 5.5 mm.

Doll

The pupa is 3.25 to 3.7 mm long with a diameter of 0.7 to 0.8 mm. It is orange, light brown to dark brown. The wing covers are long, the antenna covers almost reach the top of the abdomen. She doesn't have a cremaster . But it has a pointed head. A characteristic feature of the pupa of the horse chestnut leaf miner is that the second to sixth abdominal segments each have a pair of inwardly curved thorns, which presumably serve to anchor the cocoon in the cocoon or to anchor the cocoon to the upper leaf epidermis during hatching. The dolls show a sexual dimorphism; in the males the sixth and seventh abdominal segments are slightly longer; the seventh segment is also a little wider.

The haploid chromosome set is 30.

Similar species

The closest related species of the horse chestnut leaf miner probably lives in Japan. The " Cameraria niphonica Kumata 1963" found on Kyūshū and in the south of Hokkaidō differs only slightly from the European species in the genital apparatus. It affects three types of maples. The great majority of the Cameraria species live in North America, where they attack different plant families. In North America only one species of the genus Cameraria , Cameraria aesculisella , attacks tree species of the genus Aesculus . However, it differs significantly from the horse chestnut leaf miner.

Geographical distribution

The original range of the horse chestnut leaf miner are stocks of the common horse chestnut ( Aesculus hippocastneum L.) in Albania , Macedonia , northern and central Greece and probably also in eastern Bulgaria . This was the result of studies on specimens of the common horse chestnut from numerous herbaria dating back to 1879. Another confirmation of the origin of the horse chestnut leaf miner from the southern Balkans and Greece can be found in the genetic diversity of the populations. Romain Valade et al. found 25 different haplotypes (A – Z) of the horse chestnut leaf miner in the natural stocks of the common horse chestnut. In the current area of distribution, however, they only found three haplotypes (A, B, C), with haplotype A also dominating. Other different haplotypes were found by David Lees et al. 2011 when examining herbarium material in Greece. The genetic diversity of the horse chestnut leafminer populations in Central Europe is greatly reduced compared to the original population, as they only go back to a few specimens ( founder population ) that were introduced to Austria at the end of the 1980s.

Although the moths are able to fly, they only actively fly short distances. The light build and the fringed rear wings allow passive flying and spreading through the wind. In addition, the leaf miner is spread by humans via travel and transport routes.

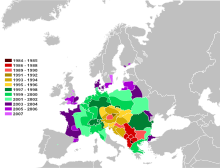

Spread since 1984

The horse chestnut leaf miner was first discovered in Macedonia in 1984 near Lake Ohrid . It was first described in 1986. One of the authors of the first description, G. Deschka, also brought samples from Macedonia with him to Linz. In 1989 it was detected for the first time in Austria (in the area of Linz and Steyr ) (a first mass increase took place here as early as 1990/91). It cannot be ruled out that some animals escaped from the breeding facilities in Linz and were thus able to jump 1000 km towards Central Europe.

Since then, the horse chestnut leaf miner has spread across Europe at a speed of around 40 to 100 km per year. In 2002 it had reached the Iberian Peninsula and the British Isles in the west, and a first infestation of the horse chestnut ( Aesculus hippostaneum ) was detected in Wimbledon (southern England). In 2010 the Scottish border had already been reached on the British Isles. In the north it has already advanced into southern Scandinavia. In the east it had reached Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus and western Russia by 2002 at the latest. In the southeast, the first cases of mass infestation were also reported from Turkey in 2002.

Way of life

The horse chestnut leaf miner usually forms three successive generations per year in Central Europe, which fly in April / May, July and mid-August to the end of September. However, under warm and dry weather conditions that are favorable for the species, up to five overlapping generations have been observed. Often, however, the fourth generation is only incompletely trained because there are no more fresh leaves available.

The first moths hatch after the winter diapause, depending on the region, from around mid-April, and under favorable conditions in northern Italy as early as the end of March. Depending on the weather, the hatching of the first moths in the same region can be delayed by one or two weeks. The head of the pupa has a pronounced beak-like protrusion that serves to open the disc-shaped cocoon and pierce the leaf epidermis. The moths hatch exclusively by breaking through the upper leaf epidermis. The doll's shell remains in the leaf mine. The hatching behavior after hibernation is defined as protandric i. w. S. to designate, d. This means that significantly more males hatch in the first 14 days and significantly more females in the following 14 days. Overall, however, the ratio of males to females is roughly the same. The hatching of the overwintering generation took 42 days in the Munich (Bavaria) region.

The moths of the spring generation stay mainly in the undergrowth and lower crown area and on the trunk. They prefer wind-turned and sunny spots. You usually sit with your head up. In the further course, the females penetrate into the upper crown areas to lay eggs. Especially the adults of the summer and autumn generation tend to stay in the crown area, especially if the leaves of the lower crown area have already been heavily used by the spring generation.

The females attract the males with the help of pheromones, which are produced by a scent gland at the rear end. Copulation follows within a few days after hatching. Often the first pairs can be seen copulating shortly after hatching. The moths are diurnal with activity peaks in the middle of the morning and around the middle of the afternoon. They are most active at moderately warm temperatures of 20 to 24 ° C.

The females then lay 20 to 82 eggs individually on the top of the leaves. With a high population density of the moths, up to 300 eggs per chestnut leaf have been observed. The moths have a lifespan of 4 to 11 days. So far there has been no observation that the moths, although they have a well-developed proboscis , eat food during their short life. The moths occur more frequently in May, July and August / September, with some latecomers until the beginning of October.

After about 4 to 21 days, the egg caterpillars hatch from the eggs and eat themselves under the leaf epidermis directly under the egg shell. A total of six, rarely seven, larval stages go through until pupation. The larval phase is divided into a feeding stage (four to five stages, L1 to L4 / L5) and a spinning stage (two stages, S1, S2). The young larvae (L1) first eat their way in a one to two mm long duct parallel to a leaf vein in the leaf, which they then continue laterally. The upper and lower epidermis of the leaf remain intact, they "mine" or form a leaf mine. L1 caterpillar is more likely to suck in juices than to eat cell tissue. From the second larval stage (L2) they then eat the palisade parenchyma , but without the leaf veins, which remain largely intact. During their feeding activity, the larvae separate the upper skin of the leaves from the underlying leaf tissue and thus cut off the water supply, causing the areas above the mines to dry out and turn brown. The L2 expands the mine to a circular shape of 2 to 3 mm, the L3 to a diameter of 5 to 8 mm. The mines, which are now irregularly widened between two leaf veins, can grow to 30 to 40 mm in size by the end of the feeding stage. If the infestation is severe, so-called community mines can arise in which several larvae develop.

At the end of the fourth (or fifth) larval stage, the larva stops feeding and begins to spin in. The first spinning stage (S1) only spins individual threads that form a space within the mine in which the caterpillar pupates. First, the first spinning stage sheds its skin into the last larval stage (S2). This larva can now show two completely different behaviors, either a solid, silk cocoon is spun, or no cocoon is spun. If a cocoon is created, it is attached to the lower leaf epidermis in the leaf mine; In this case, pupation also takes place in the cocoon. The larval phase lasts (in the Munich region) a total of 49 to 63 days.

The pupa is a covered pupa ( pupa obtecta ). The subsequent rest of the pupae is 12 to 16 days in summer or at least six months for the overwintering generation. The last generation pupae overwinter in the leaf. The disc-shaped cocoon, which is not always formed, measures around 5 mm in diameter. However, not only dolls of the last generation of the year hibernate, but also dolls of the 2nd generation (34.8%) or even the 1st generation (9.78%). These dolls go into a real winter diapause , i. That is, they need some time in freezing temperatures so that they hatch in spring when temperatures rise. For example, a three-week phase with maximum daily minimum temperatures of −1.5 ° C to +1 ° C and maximum daily temperatures of 4 to 8 ° C (under laboratory conditions) could not break the winter diapause. What ultimately triggers this winter diapause is unclear, since some first and second generation dolls can fall into the winter diapause. The pupae of Cameraria ohridella are extremely resistant to low freezing temperatures (in Pustertal / South Tyrol down to -15 / -20 ° C, in extreme cases down to -28 ° C). They endure the complete drying up or the complete watering of the leaves and even partial mold growth of the leaves. The pupae can also survive two or three winters, i.e. This means that they hatch in the spring after next or after next.

Host plants

Common horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum)

In their original range in the southern Balkans, Albania, South Macedonia and northern and central Greece, the trees of the common horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) stand individually or in small stands and are or were generally difficult to access. That is why the horse chestnut leaf miner remained undiscovered until 1984. Possible mass occurrences of the horse chestnut leaf miner were also not registered until 1984.

The results from the investigation of herbarium material are all the more astonishing. For example, dried leaves of the common horse chestnut from southern Albania, which had been collected in 1961, had an infestation with leaf mines by C. ohridella , which comes close to the current infestation of the leaves with the current mass occurrence in Central Europe. Either the mass occurrence of the horse chestnut leaf miner, which is still ongoing today, began much earlier, or there were occasional mass occurrences of the moth earlier, at least in the 1960s, which went unnoticed. Herbarium of the common horse chestnut from areas outside the southern Balkans and Greece was invariably not attacked by the horse chestnut leaf miner. The spread of the horse chestnut leaf miner outside the natural range is therefore certainly more recent.

In the last decades of the 20th century, the accessibility of the original stocks was greatly facilitated by road construction in previously inaccessible mountain regions of Greece. However, this also makes it easier for the horse chestnut leaf miner to accidentally be carried away by vehicles into these areas that were previously inaccessible to the moth.

Harmful effect

In the first centuries of its existence in Central Europe, the common horse chestnut was not endangered by diseases or predators. The guignardia aesculi , the causative agent of leaf tanning , has appeared since the 1950s . The infestation of the leaves by the horse chestnut leaf miner, which has spread throughout Europe since the 1990s, was all the more surprising.

The feeding tunnels (mines) of the larvae lead to a rapid brown coloration and thus to the slow wilting of the leaves in summer. This leads to a weakening of the tree as photosynthesis is interrupted. The trees can absorb less nutrients. They also lose their aesthetic quality, at least months earlier than if they were not infested by the horse chestnut leaf miner. So far, however, no tree death has been observed due to the horse chestnut leafminer infestation, which was initially feared. However, there is still no long-term knowledge of well over 20 years. In the long term, a weakening of the trees is to be feared, since they are prevented from assimilation by the death of the leaves . Heavily infested trees have significantly smaller fruits in autumn than those that are not or less strongly infested.

Additional negative effects from other chestnut diseases could occur in the future.

Other horse chestnuts

In Europe, the white flowering common horse chestnut is mainly grown. For a change in color, specimens of the red-flowering, but mostly somewhat smaller, red horse chestnut ( Aesculus pavia ) were also planted in the stands. For the layman, the flesh-red horse chestnut is very similar to Aesculus x carnea Hayne, a fertile hybrid of Aesculus hippocastanum and Aesculus pavia , which can be reproduced via seeds.

The first person to describe the horse chestnut leaf miner still believed in 1986 that the species was strictly monophagous on the common horse chestnut. In the meantime, however, a number of other tree species have also been observed. Among the other Aesculus species (and hybrids), Aesculus pavia and Aesculus x carnea are also attacked, but the larvae do not develop. Individual reports of infestations of red and flesh-red horse chestnuts could be related to the fact that these red-flowered horse chestnuts, which are widespread in Europe, are usually grafted on Aesculus hippocastanum in tree nurseries . So z. B. stick rashes or individual branches are definitely part of the base. This can only be distinguished at the flowering time, when flowers are formed on these branches and shoots.

Other rarely planted species of Aesculus from North America, such as the yellow horse chestnut ( Aesculus flava Sol.), The Ohio horse chestnut ( Aesculus glabra Willd.) And the bush horse chestnut ( Aesculus parviflora Walt.) Are either not attacked by the horse chestnut leaf miner or the larvae cannot develop in the leaves of these species. The Asiatic Indian horse chestnut ( Aesculus indica ) is flown to heavily and covered with eggs, but the larvae died in the first stage. On the other hand, the Japanese horse chestnut ( Aesculus turbinata ), sister species of the common horse chestnut, was found to be only slightly infested, but the mines were well developed.

Other host plants

Sycamore maple

Just a few years after the invasion of the horse chestnut miner moth in Central Europe, it was found that the sycamore maple ( Acer pseudoplatanus ) was also attacked if the tree stood under or directly next to a heavily infested common horse chestnut. At first it was thought that the larvae would not develop any further, but only a short time later living pupae were found in the leaves of the sycamore maple.

Norway maple

Even Norway maple ( Acer platanoides ) is sometimes affected. However, wherever an infestation of maple species was found, it was observed that the mortality of the larvae from predators and parasites was very high. The genus Acer is closely related to the genus Aesculus and is now placed in the same subfamily Hippocastanoideae. Several species of the genus Cameraria specialize in species of the genus Acer .

Combat

Chemical preparations

The preparation Dimilin (active ingredient: Diflubenzuron ) , which acts as a chitin inhibitor, is used to combat the horse chestnut leaf miner . Dimilin has a larvicidal (death of the larvae) and an ovicidal effect (prevents the larvae from hatching). Nevertheless, it is harmless to humans, pets, birds and beneficial insects ( bees , lacewings ). The best time to spray with Dimilin is in April / May, just before the horse chestnut blossom.

Furthermore, preparations with the active ingredients azadirachtin and methoxyfenozide are approved for combating the horse chestnut leaf miner in Germany .

Azadirachtin is the insecticidal active ingredient of the neem tree . It has a partial systemic effect (is absorbed by the treated parts of the plant and thus also reaches hidden living or mining pests); it is characterized by a pronounced anti-feeding effect and interferes with the hormonal balance of the harmful insects, it disturbs the moulting , metamorphosis and blocks the reproduction of the treated pests.

Methoxyfenozide is a synthetic active ingredient from the group of bisacylhydrazides. It acts as an ecdysone agonist by inducing the larvae to molt prematurely, causing them to die; it is a pronounced poison with a certain depth of effect and it acts selectively against the larvae of harmful Lepidoptera (moths, butterflies); in addition, it has an ovicidal effect (kills the pests' eggs). The antifeedant activity of methoxyfenozide starts soon after the pests have absorbed the active ingredient, before they die.

With glue rings on the trunks against the climbing of the spring generation of the moths after hatching, large-scale effects are achieved in some cases.

Combat with sex attractants

There are traps with sex attractants ( pheromones ) on the market. These are well suited for monitoring , but control successes have not yet been achieved with the methods tested so far.

Natural enemies

Since the horse chestnut leaf miner has only been spreading in Central Europe for a relatively short time, there are no predators who specialize in these animals. However, blue and great tits have been observed repeatedly, searching leaf by leaf in large groups of chestnuts at certain times. After observations on a large horse chestnut in the Kirchen district of the municipality of Efringen-Kirchen , for example, on August 25, 2000, July 5, 2001 and August 9, 2003, from around 2 p.m. for around 25 minutes, swarms of swarms of coordinated swarms for a few days in a row 30 to 40 blue tits. The many noises from the respective pecking of the leaf mines could be heard diagonally below on the ground. In such trees, the infestation is so limited that only part of the lower leaves fall off before autumn. Leaves higher up show the typical traces of feeding, but are otherwise green. In order to specifically attract tits to combat the horse chestnut leaf miner, nest boxes for tits were placed directly on the chestnut trees in various German cities, which visibly reduced the infestation. The BUND therefore also recommends attaching tit boxes directly to the infested chestnut trees.

The southern oak cricket has been observed to bite open the mines and eat larvae and pupae.

An additional option is to promote other natural enemies, which include ants and grasshoppers as well as parasitic wasps. About 30 parasitic parasitic wasp species are known, mainly wasps from the Eulophidae family , which parasitize in the caterpillars of the horse chestnut leaf miner, which ultimately leads to the death of the larva or pupa. In Sweden, the braconid parasitic wasp Colastes braconius was the main parasite . Two parasitic wasp species parasitize the two stages of prepupa and the pupa. Overall, the parasitization rate is very low at 7 to 10%.

In a project, Swiss researchers have collected the leaves, which contain the pupae of the horse chestnut leaf miner as well as those of the parasitic wasps, in special leaf containers. These were surrounded by a fine-meshed textile tarpaulin so that only the smaller beneficial insects could escape. The proportion of moths parasitized by parasitic wasps can thus be roughly doubled.

Missing or low parasitization generally occurs in adventitious species that have not yet been adapted (i.e. that have been carried away) and that have only recently immigrated. The species discussed is a good example of this phenomenon.

Damp weather reduces the infestation. In addition, larvae damage was observed through high internal leaf pressure, which occurs when the soil is heavily saturated.

Foliage collection

In order to reduce the moth load on the tree, the leaves of the horse chestnut must be collected and destroyed all year round so that the pupae cannot overwinter. After just 2–3 days, the larvae hide from the fallen leaves into the ground, where they overwinter. The permanent stages formed throughout the year are very resistant; unlike the foliage, the pupa does not rot. An effective destruction of the pupae is only achieved in commercial composting plants, since only here the necessary high temperatures of around 60 ° Celsius can be reached. A simple composting in the garden is not enough. Alternatively, the leaves can be burned, but not generally permitted everywhere. However, various environmental ministries in the federal states allow chestnut leaves to be burned to combat moths.

In some municipalities it is also permitted to bury leaves under a layer of soil between 10 and 50 cm thick or to shred them with a shredder or lawnmower, which can kill the pupae by over 80%.

Tree inoculation

The active ingredient Revive ® from Syngenta is approved in Switzerland. It is injected into the tree under low pressure, is mainly stored in the leaves and suppresses the development of leaf miners for several years.

literature

- Gerfried Deschka, Nenad Dimić: Cameraria ohridella n. Sp. from Macedonia, Yugoslavia (Lepidoptera, Lithocolletidae). Acta Entomologica Jugoslavica, 22, 1986, pp. 11-23.

- Jona Freise, Werner Heitland: Bionomics of the horse-chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimić 1986, a pest on Aesculus hippocastanum in Europe. Senckenbergiana biologica, 84, Frankfurt / Main 2004, pp. 61-80.

- Klaus Hellrigl: New findings and studies on the horse chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic, 1986 (Lepidoptera, Gracillariidae). In: Gredleriana. 1, 2001, pp. 9-81 ( PDF on ZOBODAT ).

Web links

- The chestnut leafminer - Beauty is a Beast ( Memento of 6 November 2009 at the Internet Archive ) - Information on the action of the SDW and background information of the LWF to the horse chestnut leaf miner

- “Horse chestnut leaf miner” flyer from the Brandenburg State Office (PDF, 344 KB) , accessed on July 28, 2011, on page 2 listing of the infected species and the severity of the harmful effect

- Butterfly and caterpillar photos on www.lepiforum.de

- Where does the horse chestnut leaf miner really come from?

- A small butterfly conquers Europe

- At the link www.cameraria.galk.de you can find everything on the subjects of biology and behavior, pheromone traps, antagonists, limits and possibilities of control, leaf collection, literature and important film sequences (DVD 2003, 43 min, German) and the current photos 2002 -2007.

- Cameraria ohridella at Fauna Europaea

- Horse chestnut leaf miner (Cameraria ohridella Deschka et Dimic) (PDF; 46 kB)

- About the origin of the chestnut leaf miner / A conversation with the director of the Botanical Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin-Dahlem, Professor H. Walter Lack In: Online magazine campus.leben of the Free University of Berlin, July 11, 2011

- Video: Biology and control of the horse chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella . Institute for Scientific Film (IWF) 2007, made available by the Technical Information Library (TIB), doi : 10.3203 / IWF / C-13171 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hubert Pschorn-Walcher: Ten years of horse chestnut leaf miner (Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic; Lep., Gracillariidae) in the Vienna Woods. In: Linz biological contributions. 33rd year, issue 2, Linz 2001 ( PDF on ZOBODAT ).

- ↑ a b Hubert Pschorn-Walcher: Field biology of the introduced horse chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella Deschka et Dimic, (Lep., Gracillariidae) in the Vienna Woods. In: Linz biological contributions. Volume 24, Linz 1994 ( PDF (662 kB) on ZOBODAT ).

- ↑ a b Christa Lethmayer: Over 10 years of Cameraria ohridella (Gracillariidae, Lepidoptera) - new beneficial insects? In: Entomologica Austriaca. 8, 2003 ( PDF on ZOBODAT ).

- ↑ idw-online.de of June 21, 2011: Highly invasive chestnut leaf miner lived in the Balkans as early as 1879: New facts on origin.

- ↑ a b c David C Lees et al .: Tracking origins of invasive herbivores through herbaria and archival DNA: the case of the horse-chestnut leaf miner. In: Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment , online publication 2011, doi : 10.1890 / 100098

- ↑ Jona Freise, Werner Heitland: A brief note on sexual differences in pupae of the horse-chestnut leaf miner, Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic (1986) (Lep., Gracillariidae), a new pest in Central Europe on Aesculus hippocastanum. Journal of Applied Entomology, 123: 191-193, 1999.

- ↑ Cameraria ohridella (horse-chestnut leaf miner) - Website by David Lees of the Natural History Museum .

- ^ Tosio Kumata: A taxonomic revision of the Gracillaria group occuring in Japan (Lepidoptera: Incurvarioidea). Insecta matsumurana. Series entomology: Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture Hokkaidō University, New Series, 26: 1-186, 1963 PDF .

- ↑ a b c Christine Tilbury, Hugh Evans: Exotic pest alert: Horse chestnut leaf miner, Cameraria ohridella Desch. & Dem. (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae). UK Government PDF .

- ↑ Romain Valade, Marc Kenis, Antonio Hernandez – Lopez, Sylvie Augustin, Neus Mari Mena, Emmanuelle Magnoux, Rodolphe Rougerie, Ferenc Lakatos, Alain Roques, Carlos Lopez-Vaamonde: Mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA markers reveal a Balkan origin for the highly invasive horse –Chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella (Lepidoptera, Gracillariidae). Molecular Ecology, 18 (16): 3458-3470, 2009. doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-294X.2009.04290.x

- ↑ a b c Leaflet on the chestnut leaf miner from the Berlin Plant Protection Office September 2012

- ↑ [1] .

- ↑ a b N. A. Straw, M. Bellett-Travers: Impact and management of the Horse Chestnut leaf-miner (Cameraria ohridella). Arboricultural Journal: The International Journal of Urban Forestry, 28 (1-2): 67-83, 2004 doi : 10.1080 / 03071375.2004.9747402

- ↑ Urban development Berlin: Flight history of the chestnut leaf miner 2003. (PDF; 13 kB) Retrieved on December 4, 2011 .

- ^ A. Svatoš, B. Kalinová, M. Hoskovec, J. Kindl, I. Hrdý: Chemical communication in horse-chestnut leafminer: Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimić. Journal Plant Protection Science, 35 (1): 10-13, 1999 abstract .

- ↑ Bogdan Syeryebryennikov: Ecology and control of horse chestnut leaf miner (Cameraria ohridella). 67 p., Shmalhausen Institute of Zoology, Kiev 2008 PDF .

- ↑ Elżbieta Weryszko-Chmielewska, Weronika Haratym: Changes in leaf tissue of common Horse Chestnut (Aesczlus hippocastanum) L.) colonized by the Horse-Chestnut leaf miner (Cameraria ochridella [sic] Deschka & Dimić. Acta agrobotanica, 64 (4): 11-22, 2011 PDF .

- ↑ Tobias Rüther Eaten chestnuts - you get the moths In: FAZ October 3, 2008, accessed on March 2, 2015.

- ↑ Peter Hummel: The chestnut leaf miner (Cameraria ohridella). (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 7, 2012 ; Retrieved December 4, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Federal Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety: List of approved plant protection products; Culture: "horse chestnut species"; Harmful organism: "Chestnut leaf miner" , accessed on July 22, 2012.

- ↑ Ishaaya, I .; Nauen, R .; Rami Horowitz, A. Eds : Insecticides Design Using Advanced Technologies. (Chap. 10: 3. Azadirachtin and Related Limonoids from the Meliaceae). Springer-Verlag, 2007. ISBN 978-3-540-46904-9 .

- ↑ Krämer, W. et al .: Modern Crop Protection Compounds, Volume 3: Insecticides. 2nd Ed. (Chap. 28: Bisacylhydrazines: Novel Chemistry for Insect Control). Wiley-VCH, 2012, ISBN 978-3-527-32965-6 .

- ↑ Umweltbericht Helmstedt 2005/2006 ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Nest boxes are supposed to save chestnuts , article in the Nassauische Neue Presse from March 2, 2017, last viewed on June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Titmouse against leaf miners , article in Volksstimme of March 1, 2016, last viewed on June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original dated August 30, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Article of the BUND local groups Jüchen, last viewed on June 17, 2017.

- ↑ G. Grabenweger, P. Kehrli, B. Schlick-Steiner, F. Steiner, M. Stolz, S. Bacher: Predator complex of the horse chestnut leafminer Cameraria ohridella: identification and impact assessment. Journal of Applied Entomology, 129 (7): 353-362, 2005 doi : 10.1111 / j.1439-0418.2005.00973.x

- ↑ Gieselher Grabenweger, Patrick Kehrli, Irene Zweimüller, Sylvie Augustin, Nikolao Avtzis, Sven Bacher, Jona Freise, Sandrine Girardoz, Sylvain Guichard, Werner Heitland, Christa Lethmayer, Michaela Stolz, Rumen Tomov, Lubomir Volter, Marc Kenis: Temporal and spatial variations in the parasitoid complex of the horse chestnut leafminer during its invasion of Europe. Biologic Invasions, 12 (8): 2797-2813, 2010 doi : 10.1007 / s10530-009-9685-z .

- ↑ Birgitta Rämert, Marc Kenis, Elisabeth Kärnestam, Monica Nyström, Linda-Marie Rännbäck: Host plant suitability, population dynamics and parasitoids of the horse chestnut leafminer Cameraria ohridella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) in southern Sweden. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B - Soil & Plant Science, 61 (5): 480-486, 2011 doi : 10.1080 / 09064710.2010.501341

- ↑ Lubomír Volter, Marc Kenis: Parasitoid complex and parasitism rates of the horse chestnut leafminer, Cameraria ohridella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia. European Journal of Entomology, 103: 365-370, 2006 ISSN 1210-5759 .

- ↑ Gerfried Deschka: Contribution to the population dynamics of Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic (Gracillariidae, Lepidoptera, Chalcididae, Ichneumonidae, Hymenoptera) , Linzer Biological Contributions, 27/1, Linz 1995.

- ↑ [2] accessed on February 23, 2015.

- ^ The cross with the chestnut leaves Märkische Onlinezeitung, November 7, 2013, accessed on February 23, 2015.

- ↑ Dealing with autumn leaves ( Memento of the original from February 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Bürgerservice Fulda, accessed on February 23, 2015.

- ↑ Giselher Grabenweger: Effects of dust removal on Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic (Lepidoptera, Gracillariidae) and their parasitoids , Institute for Plant Protection , University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, 2001 ( PDF ( Memento of the original from October 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: Der Archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; 24 kB)

- ↑ Leaflet on leaf disposal by the Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment , accessed on February 23, 2015.

- ↑ It gets uncomfortable for leaf miners . hello, magazine for the employees of Syngenta in Switzerland, 2nd edition, September 2012, page 16 ( PDF ( Memento of the original from March 3, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check Original and archive link according to instructions and then remove this note .; 2.1 MB)

- ^ Hard times for leaf miners The Swiss House Owner, No. 6, April 1, 2013, page 25.