Scheunenviertel (Berlin)

As a barn area was formerly an in present-day Berlin district of Mitte , close to the historic center lying area north of the city wall between the Hackescher Markt and today's Rosa-Luxembourg-Platz referred.

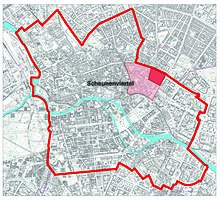

The entire area between Friedrichstrasse and Karl-Liebknecht-Strasse is often referred to as the Scheunenviertel, which is bordered in the south by the Stadtbahn (roughly the course of the old city wall) and the Spree , and in the north by Linienstraße or Torstrasse . In fact, the Scheunenviertel only includes the part of the Spandauer Vorstadt east of Rosenthaler Straße . The eponymous Scheunengassen were only in the area of today's Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, delimited by today's Almstadtstraße (west), Hirtenstraße (south), Linienstraße (north) and Kleine Alexanderstraße (east). None of the barn alleys exist in their former form.

history

Prussia

In 1670, the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm forbade the maintenance of barns within the city for fire protection reasons , and around 1672 he ordered the construction of 27 barns in the immediate vicinity of the former city wall. This is how today's Scheunenviertel came into being . The Alexanderplatz was a livestock market at that time for its operation large amounts of hay and straw were needed. Since the fire protection regulations forbade the storage of such inflammable materials inside the city wall, the barns were built outside the wall. To the north of today's Dircksenstrasse, which marks its approximate course in front of the baroque city fortifications, there were extensive agricultural areas. The Scheunenviertel also served as a home for the farm workers employed there. After the city wall was torn down, the area was built on, but kept its old name in popular parlance.

In 1737 Friedrich Wilhelm I ordered all Berlin Jews who did not own a house to move to the Scheunenviertel. This law and the regulation that Jews were only allowed to enter the city through the two northern city gates led to the creation of a quarter with strong Jewish cultural influences at this point. In addition to the Heidereutergasse synagogue , the Berlin-Mitte Jewish cemetery and the Schönhauser Allee Jewish cemetery were built in the immediate vicinity of the Scheunenviertel.

Given these conditions, it was obvious for many East Jewish immigrants to settle here as well when they came to Berlin from the middle of the 19th century. This quickly led to a rapidly growing number of residents in this area. In a confined space, the families had to share their living room with sleeping lads in shifts . A typical branch of business in the second half of the 19th century was the emerging cigarette production with all family members.

Industrialization period

The process of industrialization left serious traces in the Scheunenviertel. After the establishment of the German Empire in 1871, Berlin became the largest industrial city in Europe. The population density increased rapidly within a few years, the housing requirements of the migrant workers were only belatedly and insufficiently reduced by the construction of tenement barracks in the newly emerging districts. The small-scale old buildings in the Scheunenviertel were cramped. Many newcomers found their first home here. The scarce sleeping places in the sublet apartments were often shared in the same way as the shifts in the nearby Borsig works . Those who neither slept nor worked stayed in the streets or spent their little free time in one of the numerous bars in the district (for example in the so-called “Mulackei” or “ Mulackritze ” around Mulackstrasse ). The Grenadierstraße developed at this time to the main street of the Orthodox Eastern European Jews, often referred to as "ghetto with open doors."

Because of the catastrophic structural and social situation, the Berlin magistrate decided to completely redesign the district from 1906/1907. Until then, four of the original eight barn alleys were still available, but after many buildings were demolished, the road network around Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz was redesigned:

- First Scheunengasse - currently built over

- Second Scheunengasse - currently: Rosa-Luxemburg-Strasse (with a different street course)

- Third Scheunengasse - currently: Zolastraße (only this part is still based on the old course of the street, but is only an extension to Linienstraße that did not exist at the time)

- Vierte Scheunengasse - currently: Weydingerstraße (with a different street course)

- Kleine Scheunengasse - currently built over

However, because of the First World War , the redesign of the entire quarter was canceled, so that the old building fabric is still present in the western area, while modern buildings from the first decades of the 20th century dominate the square.

Scheunenviertel pogrom 1923

During the Weimar Republic , the Scheunenviertel was repeatedly the target of police raids and anti-Semitic pogroms . In the early 1920s, the Berlin police chief Wilhelm Richter ordered a major raid against the Jewish population in the Scheunenviertel, during which around 300 Jewish men, women and children were picked up by the police and interned in a "Jewish camp" near Zossen .

In the course of the progressive hyperinflation , thousands of unemployed people gathered in front of the employment office in Gormannstrasse on November 5, 1923 to collect support money. After a short time, the crowd was informed that there was no more money to be paid out. Agitators then approached the angry crowd, saying that “Galicians” ( Eastern Jews ) from the Scheunenviertel had planned to buy up the money. Soon riots began in the Scheunenviertel with its backyards and hawkers, which were directed against all people and businesses that the crowd considered "Jewish". People were dragged out of their homes and beaten and business facilities were vandalized. In contemporary newspapers such as the Vossische Zeitung one could read that the police had noticeably restrained themselves during the riots, when it would have been easy for them to contain the crowd.

The confusion of names

The Scheunenviertel is often equated with the Spandau suburb. This has the following historical background: At the beginning of the 20th century, the Scheunenviertel had developed into a social hotspot. The quarter was characterized by poverty , prostitution and petty crime and had a corresponding reputation among the Berlin population. The first ring club , a criminal organization, was founded in the Scheunenviertel in 1891 . In the western part of the Spandau suburb, however, a middle-class, Jewish-influenced milieu had established itself. The Reformed Jewish Community with the New Synagogue ( Oranienburger Strasse ) also had an important center here. In order to vilify the Jews residing in the western Spandau suburb, the National Socialists extended the disreputable name Scheunenviertel to the entire Spandau suburb, i.e. wrongly also to Oranienburger Strasse with the New Synagogue.

The term Scheunenviertel is no longer associated with the formerly negative meaning, but stands for the “ trendy district ” established after 1990 . Designer fashion is sold around Neue Schönhauser Strasse. But the proximity to Hackescher Markt, Oranienburger Strasse and Kastanienallee also make the area attractive.

literature

- Wolfgang Feyerabend et al. : The Scheunenviertel and the Spandau suburb . L&H Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-939629-38-2 .

- Eike Geisel : In the Scheunenviertel. Images, texts and documents . With a foreword by Günter Kunert . Severin & Siedler, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-88680-016-4 .

- Hans Jörgen Gerlach : disease focus or fairy tale shtetl. Martin Beradt looks on both sides of the street . In: Zwischenwelt. Journal for the Culture of Exile and Resistance , 20th year, No. 2; Vienna September 2003, pp. 74/75. ISSN 1606-4321

- Horst Helas: Jews in Berlin-Mitte. Biographies - places - encounters . (Edited by the Association for the Preparation of a Foundation Scheunenviertel Berlin e.V.). trafo Verlag Wolfgang Weist, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89626-019-7 .

- Ulrike Steglich, Peter Kratz: The wrong Scheunenviertel - a suburban seducer . Altberliner Bücherstube, Verlagbuchhandlung Oliver Seifert, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-930265-00-1 .

- Anne-Christin Saß: Scheunenviertel. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 5: Pr-Sy. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2014, ISBN 978-3-476-02505-0 , pp. 352-358.

Web links

- Research project “Scheunenviertel” of the Free University of Berlin

- Karl Heinz Krüger: In the neighborhood of poor people . In: Der Spiegel . No. 7 , 1991 ( online ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ulrike Steglich, Peter Kratz: The false Scheunenviertel, Berlin 1997, p. 205

- ↑ Martin H. Geyer: Capitalism and Political Morality in the Interwar Period or: Who Was Julius Barmat? Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-86854-319-3 .

- ^ MDR time travel: Buchenwald - A concentration camp in the middle of us . MDR television, 2020.

- ↑ It started at the employment office. In: Berliner Zeitung , November 5, 2003

- ↑ Crooks found the first ring club in Berlin. ( Memento of the original from January 11, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

Coordinates: 52 ° 32 ' N , 13 ° 25' E