Sea battle at Coronel

| date | November 1, 1914 |

|---|---|

| place | at Coronel , Pacific |

| output | German victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 2 armored cruisers 1 light cruiser 1 auxiliary cruiser |

2 armored cruisers 3 light cruisers |

| losses | |

|

2 armored cruisers |

3 wounded |

In the waters off Coronel in the then neutral Chilean waters, a sea battle took place on November 1, 1914 between the German East Asia Squadron under Vice Admiral Maximilian Graf von Spee with the large cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the small cruisers Leipzig and Dresden and a British squadron under Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock with the armored cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth , the light cruiser Glasgow and the auxiliary cruiser Otranto . The German small cruiser Nuremberg arrived towards the end of the battle, while the old and slow British liner Canopus did not reach the battlefield in time.

prehistory

Coming from the Pacific, the German squadron stayed in Cook's Bay of Hanga Roa on the Chilean Easter Island from October 12th to 18th . Besides the five cruisers (the Leipzig had only arrived from Mexico on October 14th), the supply ships Baden , Titania , Göttingen , Yorck , Amasis , Anubis and Karnak belonged to Admiral Spee's armed forces. After the one-week coal bunker, the empty coal ships Anubis and Karnak were released. The rest of the squadron steered past Salas y Gómez at a speed of 10 knots towards the Chilean coast. At a commanders' meeting on October 24th, Spee announced his decision to put the enemy in battle and to take them out in order to break through into the Atlantic.

On October 26th, Spees charred cruisers on the west side of Mas Afuera Island . Spee only let Leipzig break the radio silence to give the impression that she was alone.

Rear Admiral Cradock was appointed commander of a British cruiser group off the Brazilian coast in early September. In the weeks leading up to the meeting of the two squadrons, he repeatedly expressed his concerns to the Admiralty regarding the numerical inferiority of his ships, but fell on deaf ears with the First Lord of the Admiralty (Minister of the Navy) Winston Churchill . On October 21, he left Port Stanley with his ships and drove through the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific. From October 26th he anchored in the bay of Vallenar in the Chonos archipelago . The Glasgow ahead caught the radio messages from Leipzig . Cradock's armored cruiser Good Hope and Monmouth then set out from Vallenar Bay on October 30th to confront the supposedly single Leipzig . The Glasgow arrived in Coronel on October 31st . There she was discovered by Germans, and Göttingen , which had just arrived in Coronel just like the Yorck , lifted anchor again and radioed outside the three-mile zone at 02:50 on November 1st: "Cruiser Glasgow anchored in Coronel roadstead." Spees' squadron marched immediately south at 14 knots to intercept the Glasgow .

The battle

The Glasgow , however, had since left Coronel and had rejoined Cradock's association. He waived the support of the Canopus, which only sailed at a maximum of 12 knots, and marched on alone with his faster cruisers.

With the Germans, the Nürnberg , which had searched a steamer and a sailor , fell 25 nautical miles behind. The Dresden ran about 10 nautical miles behind the armored cruisers so as not to lose contact.

At 4:17 p.m. the Scharnhorst's lookout reported : “Two ships sighted in the west!”. These were the Glasgow and the Otranto , with which the Monmouth was still. Spee let the bandage form a keel line and ran south at 22 knots. The British ships turned and ran south-west to join the Good Hope coming from there . Cradock's flagship took the lead in the British squadron and also steered south to get close to the Canopus . Because of the slow Otranto , Cradock's formation could only run 16 knots. A wind with a strength of 7 to 8 from the south-east made it difficult to use the casemate guns on both sides , as they were often hindered by splashing water or high waves due to their low height above the waterline. In terms of artillery, the opponents were not equal. The heavy guns on the British side had two individual 23.4 cm guns on the Good Hope against a total of twelve 21 cm guns on the two German armored cruisers. The British Monmouth had no larger caliber than 15 cm. In addition, the two German large cruisers had a well-trained crew, although half a year ago, and a modern fire control system. In contrast, the British association had old ships like the armored cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth , both of which were only reactivated after the outbreak of war, and the large number of difficult-to-use casemate guns on the ships.

For about two hours Graf Spee let his ships follow the British on a parallel course in order to wait for the sunset in the west - his aim was to take up a favorable artillery position in which his ships were barely visible against the dark eastern evening sky and the Chilean coast while the British were clearly visible against the sharp western sunset. Shortly after 6 p.m. Cradock tried in vain to catch the Germans, who were out of firing range, but because of the unfavorable situation - the German ships would have been blinded by the setting sun during a battle - they withdrew from this attempt, and then stayed on his southern one Course.

Twilight set in at 18:20, which made the British ships in the west stand out clearly from the evening sky, while the German cruisers in the east became almost invisible. Cradock steered his flagship Good Hope from 18:18 in a south-easterly direction. Spee waited until the somewhat retarded Dresden came up.

At 6:34 p.m. the Germans opened fire for 11 kilometers. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau fired at the British armored cruisers, Leipzig at Glasgow and Dresden at Otranto . With the third volley, the Scharnhorst scored a hit on the Good Hope , and the Gneisenau soon reached the finish line at the Monmouth . Within five minutes, the Monmouth's forward turret and the Good Hope's command post were destroyed. The British answered the German fire immediately, but in addition to the poor visibility for them, the heavy seas rolling in from the southeast also proved to be an obstacle for their 6 "/ 152 mm casemate guns .

Already at 6:50 p.m. the Monmouth left the battle line on fire and tried to escape. The two German large cruisers now united their fire on the Good Hope . This received as many hits as the Monmouth and only fired single shots. At 7:23 p.m. a violent explosion could be observed on her, a little later the blazing fire disappeared. The British flagship had just sunk after an ammunition chamber explosion.

The Leipzig hit the Glasgow once at the stern and once at the forecastle, another hit was a dud . The auxiliary cruiser Otranto fled burning after the third volley and a hit from Dresden , so that Dresden could change its target to Glasgow . This received five waterline hits until the now prevailing darkness prevented further fire. Shortly after 7:30 p.m., the Glasgow stopped fire and disappeared.

The two German top ships had stopped fire at 19:26. The fires on the Monmouth were now out. She turned on a west course at around 7:35 p.m. and about an hour later on a north course to put the stern against the sea. Glasgow and Otranto, on the other hand, were looking for the Canopus .

The Leipzig headed for a firelight and drove through a field of rubble that was the remains of the Good Hope . In the meantime the moonlight improved the visibility. At 20:05, the behind-propelled sighted Nuremberg to Glasgow , but was out of sight. Instead, she met the severely damaged Monmouth , and at 20:50, Captain Schönberg opened fire at a distance of 1,000 meters. The distance dropped to 600 meters, but a shot torpedo still did not hit. The Monmouth did not return fire, but remained flagged and turned towards the Nürnberg . The Nürnberg sat down behind the stern of the Monmouth at high speed and shot 105 shells at the wreck, which was lying crooked in the sea, at the shortest possible distance. At 8:15 p.m., Nürnberg reported the sinking to the head of the association by radio. However, this turned out to be premature, because the Monmouth actually capsized and sank only at 20:58.

After the battle

At 9:50 p.m. Spee set his armored cruisers north and at 10 p.m. let the small cruisers form a reconnaissance line. From 11 p.m. the squadron searched for the escaped British ships along the Chilean coast.

1700 British seamen died, including Admiral Cradock, while there were only minor losses and combat damage on the German side. The Scharnhorst had received two hits , the Gneisenau four, the small cruisers received no hits. The two armored cruisers alone had fired 42% of their 21 cm ammunition and no replacement options.

The responsibility for the first defeat of the Royal Navy after the Battle of Plattsburgh against the USA in 1814 was blamed on the British side on the First Sea Lord (military head of the Navy) Prince Ludwig Alexander von Battenberg , who had failed to land the Royal Marines in Antwerp, in support of Belgium and its German roots, had shortly before been urged by Churchill to resign. This fortunate coincidence for him enabled Churchill to evade his responsibility for the fiasco and take the necessary measures to destroy the German squadron after all.

After the battle, Graf Spee decided to break into the Atlantic due to the poor supply situation for his units . There the German squadron was destroyed on December 8, 1914 by British units, including two battle cruisers, in the battle near the Falkland Islands with the exception of SMS Dresden and SMS Emden, who had been released months before the battle .

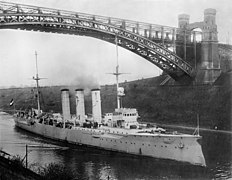

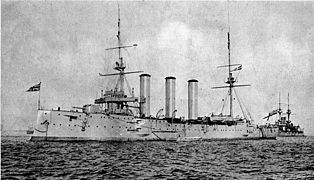

photos

- The commanders and the ships involved

Trivia

Some of the mountains of the Coast Mountains along the Canadian Pacific coast are named after the ship names used in the naval battle at Coronel, such as the 2656 m high Mount Dresden , which was climbed again in 2006 for the 800th anniversary of the city.

Individual evidence

- ↑ welt.de of November 28, 2014: The Great World War II defeat of the Royal Navy , accessed on June 6, 2016.

- ↑ bundesarchiv.de of December 2, 2014: The Sea Battle of Coronel 1914 ( Memento of the original of May 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed June 6, 2014.

- ↑ Hermann von Fischel : Speed. A tactical consideration. MDv (Marine Service Regulations) No. 352 Issue 5, Reichswehr Ministry Berlin 1929, p. 36.

- ↑ Excerpt from a letter from Kapitänleutnant Busch (1st artillery officer SMS Gneisenau ) with a description of the fire fighting of the artillery in the sea battle of Coronel in the Federal Archives, accessed on August 29, 2016. ( Memento of the original of March 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info : The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Report of the commander of Nuremberg on the sinking of the British armored cruiser Monmouth (November 1, 1914) in the Federal Archives, accessed on August 29, 2016. ( Memento of the original of March 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Excerpt from a letter from Kapitänleutnant Busch (1st artillery officer SMS Gneisenau ) with information on the hits and wounded on board the Gneisenau in the sea battle of Coronel in the Federal Archives, accessed on August 29, 2016. ( Memento of the original from November 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Overview of the ammunition consumption of the cruiser squadron in the sea battle of Coronel in the Federal Archives, accessed on August 29, 2016. ( Memento of the original from March 5, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Don Ser: Coast Mountains Roundup , 8 December 2006, accessed on September 15, 2013.

literature

- Geoffrey Bennet: The sea battles of Coronel and Falkland and the sinking of the German cruiser squadron under Admiral Graf Spee (= Heyne books. 5697). Translated, supplemented with notes and an afterword by Reinhard K. Lochner. Heyne, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-453-01141-4 .

- François-Emmanuel Brézet: La bataille du cap Coronel et des Falklands. Croisière sans return. L'escadre de croiseurs du vice-amiral Graf von Spee. Marines Éditions, Nantes 2002, ISBN 2-909675-87-4 .

- Hans H. Hildebrand, Albert Röhr, Hans-Otto Steinmetz: The German warships. Biographies. A mirror of naval history from 1815 to the present day. 7 volumes (in 2 volumes). Mundus, Ratingen 1985, ISBN 3-88385-028-4 .

- Andreas Leipold: The German naval warfare in the Pacific in the years 1914 and 1915 (= sources and research on the South Seas. Series B: Research. 4). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-447-06602-0 .

- Robert K. Massie : Castles of Steel. Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. Jonathan Cape, London 2004, ISBN 0-224-04092-8 .

- Michael McNally: Coronel and Falklands 1914. Duel in the South Atlantic (= Campaign. 248). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2012, ISBN 978-1-84908-674-5 .

- Maria Teresa Parker de Bassi: Cruiser Dresden. Odyssey of No Return. Koehler, Herford 1993, ISBN 3-7822-0591-X .

- Elmar B. Potter, Chester W. Nimitz : Sea power. A history of naval warfare from antiquity to the present. Bernard & Graefe, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7637-5112-2 .

- Erich Raeder : The cruiser war in foreign waters (= The war at sea 1914-1918. ). 2 volumes. Mittler, Berlin 1922–1923.

- Gerhard Wiechmann (ed.): From foreign service in Mexico to the sea battle of Coronel. Sea captain Karl von Schönberg. Travel diary 1913–1914 (= Small series of publications on military and naval history. 9). Winkler, Bochum 2004, ISBN 3-89911-036-6 .

See also: naval battle

Web links

- Gallery of the German Federal Archives on the sea battle at Coronel

- Exhibition at the Google Cultural Institute on the sea battle at Coronel

- Batalla Naval frente a Coronel (Chile 1914) on YouTube

Coordinates: 36 ° 58 ′ 18.6 ″ S , 73 ° 46 ′ 3.7 ″ W.