Seraphimite Church

The Seraphimites were the first independent Ukrainian church in North America that consisted of followers of Bishop Seraphim. The Seraphimite Church originated independently in Winnipeg . She had no connection to any church in Europe .

Ukrainian immigrants , especially from the then Austro-Hungarian provinces in the regions of Bukovina and Galicia , began to establish their congregation and to build churches after their arrival in Canada in 1891. The newcomers from Bukovina were mostly Orthodox believers, while the immigrants from Galicia came mostly from Eastern Catholic churches . The parishes used the Orthodox Byzantine rite known to them from their homeland . By 1903, the number of Ukrainian immigrants in western Canada was large enough to attract the attention of religious leaders, politicians, and educators for their interests.

The first church was the 'scrap iron cathedral' ( English Tin Can Cathedral or Scrap-Iron Cathedral , Ukrainian Бляшана Катедра Bljashnaja katedra ) in Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada ⊙ .

Principals

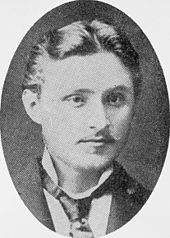

The central figure in the Ukrainian community in Winnipeg at this time was Cyril Genik (1857–1925), who came from Galicia . After graduating from a Ukrainian high school in Lviv and briefly studying law at the University of Chernivtsi . he left his home. Genik was a friend and best man Ivan Frankos , whose book Лис Микита ( Fox Nikita ) branded the clergy with biting satire and also showed socialist inclinations. Franco called for land reform in favor of poor peasants and settlers, as well as the liberation of the people from the tutelage of the clergy. After arriving in Canada, Genik was employed by the Canadian government as an immigration agent under the Dominion Lands Act to assign land and farms to the newly arrived settlers. Elementary school teachers Iwan Bodrug (1874–1952), his cousin and friend Iwan Negrich (1875–1946) also came from Bereziv near Kolomyja in Galicia. The three men formed the core of the leadership of this Ukrainian community and became known as the Bereziv Triumvirates (Березівська Трійця). Genik was the oldest of the three and the only one already married. His wife Pauline (nee Tsurkowsky) was the daughter of a priest, an educated woman; they had three sons and three daughters.

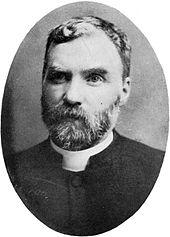

The other main figure was Bishop Seraphim, real name Stefan Ustvolsky , removed from his priesthood by the Russian Holy Synod in St. Petersburg . According to his own account, his journey began when he traveled to Mount Athos for personal reasons and was consecrated there by Bishop St. Anphim . Today it is believed that Saint Anphim actually consecrated Bishop Seraphim alias Ustvolsky. He had done this in spite of the Russian tsar , who at the time was in dispute with the Holy Synod over the violence of the Russian Orthodox Church (he had brought this story with him to the New World). As a supposed bishop , Seraphim traveled to North America, where he was supposed to stay in Philadelphia with some Ukrainian priests . When he arrived in Winnipeg, he showed no loyalty to the Russian Orthodox Church or anyone else and stayed in Canada. The Ukrainians in the rural areas accepted him as a traveling holy pilgrim , a tradition that goes back to the beginnings of Christianity .

Another person who was involved in the events of the Scrap Iron Cathedral at that time was Seraphim's assistant Makarii Marchenko . Marchenko acted as deacon and cantor and assisted Seraphim in worship . He met Seraphim in the United States and came to Winnipeg with him. The Roman Catholic Archbishop Adélard Langevin of the Archbishopric of Saint-Boniface in St. Boniface and head of the Roman Catholic Diocese in Western Canada saw that his priests were no longer serving the needs of the Ukrainian population in Canada. Another person involved in this process was William Patrick, the director of the Manitoba college of the University of Winnipeg , a Presbyterian college in Winnipeg and the Liberal Party of Manitoba and also a Russian Orthodox missionary .

Origin and development

The leadership of the community asked for help from Canadian politicians to erect a church building. The Canadian politician, member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba (English Legislative Assembly of Manitoba ) Joseph Bernier, took it upon himself, invoking a law of 1902 that said: The "The good of the Greek Ruthenians is to be promoted ( Ukrainians were also called Ruthenians ) and their Uniate Church was under sovereignty and communion with Rome . " Archbishop Langevin declared, "The Ruthenians, like Catholics, must prove that they possess the property of their church, and not like Protestants ... to an individual or a committee of lay people and independently of the priest or bishop." The size of the Ukrainian population in the rural areas had also attracted the interest of the Russian Orthodox missionaries, but this should be avoided. At that time, the Russian Orthodox Church was spending about $ 100,000 a year on missionary work in North America. In order to interest the Ukrainian immigrants in the Presbyterian Church , he invited young men from the Ukrainian community from Manitoba College (now the University of Winnipeg ), where special courses were offered for young Ukrainians who wanted to become priests in the newly formed Independent Orthodox Church . The director of the university, Dr. King, interviewed Bodrug and Negrich in fluent German. Genik translated her school documents from Polish into English. They became the first Ukrainian university students in North America. Manitoba College was affiliated with the University of Manitoba at the time.

Genik, Bodrug, and Negrich did much to consolidate their community. They came to Winnipeg in April 1903 and brought Bishop Seraphim with them to maintain their congregation's independence from European churches. With Seraphim the Ukrainian Orthodox Church got its head. In order to appease the Ukrainians at the same time, the community was called the Seraphimite Church . They celebrated the familiar Byzantine rite . Bishop Seraphim began to ordain or consecrate priests, cantors and deacons . In December 1903, the building on the east side of McGregor Street between Manitoba and Pritchard Avenue was consecrated to the Holy Spirit Church by Bishop Seraphim. In November 1904, construction began on the Scrap Iron Cathedral from scrap metal and wood on the corner of King Street and Stella Avenue. It was consecrated with around 50 priests and numerous deacons. The clergy included a large number of uninformed readers, which initially led to difficulties in carrying out priestly duties in the Ukrainian settlements. Seraphim preached an independent Orthodoxy and insisted on own fiduciary possession of ecclesiastical property. In two years the church had nearly 60,000 followers.

Due to various indiscretions and problems with alcohol, Seraphim lost the trust of his supporters who originally brought him. They tried to get Seraphim to leave and at the same time not to lose trust in their community themselves. Seraphim went to St. Petersburg to obtain official recognition and further funding from the Russian Holy Synod for the Seraphimite Church. In his absence, Iwan Bodrug and Iwan Negrich, who were theology students at the Manitoba colleague, as well as other priests of the Seraphimite Church, organized their own help and obtained guarantees for the further financing of the Seraphim Church with the aim that it would gradually follow the Presbyterian model . In the late autumn of 1904, Seraphim returned from Russia , but brought no guarantees «пособія». Upon his return, he discovered the betrayal and promptly excommunicated all priests involved. He published profile-like pictures of the alleged traitors in the local press, with names printed on his chest. His vengeance proved short-lived. It soon became known that he himself had been excommunicated by the Russian Holy Synod. The following statement is recorded: "... if the Holy Synod and the Seraphim excommunicated all his priests, he would leave them in 1908, never to return. ..."

aftermath

The differences that arose after the construction of the scrap iron cathedral and the founding of the first "Seraphimite Congregation" led to the further independence of the resident Ukrainian believers. As a result of this religious power struggle for the sovereignty and direction of the "Seraphimites", one of the first independent Ukrainian-Canadian communities in Canada emerged.

Iwan Bodrug, one of the deviants from the Seraphimite Church, subsequently became head of the new independent church and was a charismatic priest with his own right. He preached a more Protestant Christianity due to his evangelical-Presbyterian influence. He lived until the 1950s.

The Holy Spirit Church first used by Seraphim was demolished. The second Presbyterian building is on the North End of Winnipeg. The churches were built independently on the corner of Pritchard Avenue and McGregor Street.

Catholic Archbishop Langevin increased his efforts to assimilate the Ukrainian community into the Roman Catholic community . He founded the Basilian Church of St. Nicholas with the Belgian priest Father Achille Delaere and other clerics from the Congregation of St. Basil , which also Altkirchenslawisch could read and were dressed according to the Byzantine-Greek rite and sermons in Ukrainian in Polish hold could. Its church was built across the street from the independent Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral of St Vladimir and Olga on McGregor Street in North End Winnipeg. Such competition also offered Ukrainian-Canadian children a greater chance to learn and speak the Ukrainian language .

The Liberal Party of Canada was aware that the Ukrainians no longer allied themselves with Archbishop Louis-Philippe Adélard Langevin . The Roman Catholic Church, which was more oriented towards the Conservative Party , financed the first Ukrainian newspaper in Canada, The Canadian Farmer (Канадійскій Фермер). The first editor was none other than Iwan Negrich.

Seraphim disappeared around 1908, but it was still reported in the "Ukrainian Voice" (Український Голос, appears to this day in Winnipeg). According to these reports, by 1913 he was believed to have been selling Bibles to workers at the British Columbia railroad construction company . In other transmitted versions of history, he returned to Russia.

Cyril Genik moved with his eldest daughter and one of his sons to the United States in North Dakota , from where he returned to Canada after a few years and died there in 1925.

Makarii Marchenko declared after Seraphim's departure that he was not only the new bishop of the Seraphimite Church, but also the Arch- Patriarch and Archbishop. Not all parishioners welcomed this development and Seraphim's excommunication. Marchenko describes in his travel reports about his pastoral work in the 1930s with the Canadian Ukrainians in the rural areas of Canada, the decline of the Eastern rite.

literature

- Bodrug, Ivan. Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903–1913 , translators: Bodrug, Edward; Biddle, Lydia, Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982.

- Stella Hryniuk: Genyk, Cyril . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- Manitoba Free Press , issues of October 10, 1904, January 20, 1905, December 28, 1905.

- Martynowych, Orest T., The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches, umanitoba.ca/...canadian.../05_The_Seraphimite_Independent_Greek_Presbyterian_and_United_Churches.pdf -

- Martynowych, Orest T. Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924 . Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991.

- M. Maruschak. The Ukrainian Canadians: A History , 2nd ed., Winnipeg: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, 1982.

- Mitchell, Nick. The Mythology of Exile in Jewish, Mennonite and Ukrainian Canadian Writing in A Sharing of Diversities , Proceedings of the Jewish Mennonite Ukrainian Conference, “Building Bridges”, General Editor: Stambrook, Fred, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1999.

- Mitchell, Nick. Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theater in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994 , Editors: Oleh W. Gerus; Iraida Gerus-Tarnawecka; Stephan Jarmus: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg.

- Winnipeg Tribune , issue of February 25, 1903.

- Yereniuk, Roman: A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada .

Web links

- Kievan Rus

- Five Door Films, Romance of the Far Fur Country

- Hryniuk, Stella : Cyril Genik. Dictionary of Canadian Biography , accessed January 17, 2013 .

- Hryniuk, Stella : Bishop Seraphim. Dictionary of Canadian Biography , accessed January 17, 2013 .

- Martynowych, Orest T., The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches (PDF; 5.0 MB)

- Tin Can Cathedral by Nick Mitchell

- Orysia Paszczak Tracz: Our Christmas: nothing's really changed. The Ukrainian Weekly , 1998, accessed January 17, 2013 .

- University of Manitoba Libraries: Winnipeg Building Index. Tin Can Cathedral Selkirk Avenue 1904

- Yereniuk, Roman, A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada (PDF; 602 kB)

- Православная Церковь Всероссийского Патриаршества

Individual evidence

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, p. 170.

- ↑ Ivan Franko; William Kurelek; Bohdan Melnyk: Fox Mykyta. Tundra Books, 1978. Montreal. ISBN 0-88776-112-7 .

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, p. 170.

- ↑ Stella Hryniuk: Genyk, Cyril . In: Dictionary of Canadian Biography . 24 volumes, 1966–2018. University of Toronto Press, Toronto ( English , French ).

- ^ Nick Mitchell: Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theater in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994, Editors: Oleh W. Gerus; Iraida Gerus-Tarnawecka; Stephan Jarmus: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg, p. 226.

- ↑ Nick Mitchell: The Mythology of Exile in Jewish, Mennonite and Ukrainian Canadian Writing in A Sharing of Diversities, Proceedings of the Jewish Mennonite Ukrainian Conference, “Building Bridges”, General Editor: Fred Stambrook, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, 1999, p. 188.

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, p. 184.

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, p. 189.

- ^ Winnipeg Tribune February 25, 1903.

- ↑ Mitchell, Nick. Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theater in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994, editors: Oleh W. Gerus; Iraida Gerus-Tarnawecka; Stephan Jarmus: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg, p. 226.

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, p. 192.

- ↑ Roman Yereniuk: A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, www.uocc.ca/pdf, p. 9

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 1991, p. 190.

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches, umanitoba.ca/...canadian.../05_The_Seraphimite_Independent_Greek_Presbyterian_and_United_Churches.pdf -, p. 1.

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: The Seraphimite, Independent Greek, Presbyterian and United Churches, umanitoba.ca/...canadian.../05_The_Seraphimite_Independent_Greek_Presbyterian_and_United_Churches.pdf -, p. 2.

- ↑ Ivan Bodrug: Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903-1913. Translator: Edward Bodrug; Lydia Biddle: Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982, pages XII & XIII

- ↑ Yereniuk, novel, A Short Historical Outline of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada, www.uocc.ca/pdf, p. 9

- ↑ Ivan Bodrug: Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903-1913. Translator: Edward Bodrug; Lydia Biddle: Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982, p. 81.

- ^ Nick Mitchell: Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theater in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994, Editors: Oleh W. Gerus; Iraida Gerus-Tarnawecka; Stephan Jarmus: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg, p. 229.

- ↑ Bodrug, Ivan. Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903–1913 , Translator: Edward Bodrug; Lydia Biddle; Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982, p. XIII

- ↑ Orest T. Martynowych: Ukrainians in Canada: The Formative Period, 1891-1924. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Edmonton Alberta: 1991, photograph 47.

- ↑ Mitchell, Nick. Ukrainian-Canadian History as Theater in The Ukrainian Experience in Canada: Reflections 1994, Editors: Oleh W. Gerus; Iraida Gerus-Tarnawecka; Stephan Jarmus: The Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in Canada, Winnipeg, p. 229.

- ↑ Bodrug, Ivan. Independent Orthodox Church: Memoirs Pertaining to the History of a Ukrainian Canadian Church in the Years 1903–1913, Translator: Edward Bodrug; Lydia Biddle. Toronto, Ukrainian Research Foundation, 1982, p. XIII