Shanshan

The Kingdom of Shanshan ( Chinese 鄯善 , Pinyin Shànshàn , Uighur: Piçan) existed in the first centuries AD in the southeast of the Tarim Basin in what is now the Uyghur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang in the People's Republic of China . Its area extended for a length of about 750 km from Lop Nor to Niya between the Kunlun Mountains in the south and the Taklamakan desert in the north. Due to its location on the southern route of the Silk Road , it played an important role in China's trade with the West and the cultural exchange associated with it.

Research history

Due to the remoteness of Central Asia , scientific research into Shanshan's legacy did not begin until the beginning of the 20th century. In 1900 the Swedish geographer and explorer Sven Hedin was the first European to reach the Loulan area and researched several local sites. In the following years, the native Hungarian Aurel Stein traveled several times to the sites on the southern Silk Road on behalf of Great Britain. Most of the finds and excavations in the Shanshan area go back to him. At the same time, Loulan was visited twice by a Japanese expedition who found several inscriptions in particular. In the following decades, field research was suspended; Only in the last quarter of the 20th century did Chinese archaeologists carry out new excavations, particularly in Loulan.

Locations

Although Shanshan had an area of at least 75,000 km², the actual find area is limited to a few oases that are located on rivers flowing down from the Kunlun.

Loulan

Discovered in 1900 by the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin , Loulan at the western end of Lop Nor is Shanshan's easternmost site. The name of Loulan ( Chinese 樓蘭 / 楼兰 , Pinyin Loulan ) is the Chinese transliteration of a local place name in Kharosthi texts as Kroraina , in Sogdian as krwr'n , in Khotan Sakian as Raurana and in the Geographike hyphegesis the Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy as Khaurana occurs. To what extent the place name Loulan can be connected with the original name Shanshans has not yet been finally clarified. The Loulan area consists of two large fields of ruins. The most important complex in the northern group is a square city complex (LA); In their vicinity there are various unfortified settlements, some with Buddhist shrines that are extremely important in terms of art history, several burial grounds and two smaller fortresses (LE and LF). Radiocarbon dating showed that LA did not come into being until the 1st century. About 40 kilometers to the southwest there is another complex of finds, which also contained a fortified city (LK), a small fortress (LL) and an unfortified settlement (LM).

More locations

Other locations in the Shanshan area are the oases of Miran , Qakilik , Qarqan , Endere and Niya . While in Qarqan, Endere and especially Qakilik there are only insignificant ruins from the period in question, Niya and Miran are much more significant sites. In Miran Aurel Stein discovered 16 stupas with rotunda in particular , plus a Buddhist monastery complex (M II), a temple (M XV), two tower-like buildings and a Tibetan fortress built in the 8th century, i.e. after the end of Shanshan. Niya is Shanshan's westernmost site. More than 40 sites have been registered here, including a large unfortified settlement, a stupa and a few other sacred buildings. The building complex NV, in which several hundred Kharosthi texts were discovered, is of paramount importance for the research of Shanshan. Niya is also of outstanding importance from an art history perspective.

Location of the capital

The location of the capital or the capitals of Shanshan and its predecessor Loulan has not yet been clearly clarified. In the Chinese sources it is used in connection with the events around 77 BC. Chr. As 扞 泥 hànní or 扜 泥 yūní, which does not allow a clear localization. The Kharosthi texts also give no indication of the location of the royal seat. Therefore the location of the capital is controversial; however, the discussion mainly considers the northern or southern Loulan, Miran, Qarqan or Qakilik.

swell

The main sources for the history of Shanshan are Chinese histories and travelogues, which, however, can only provide a sketchy picture. In addition, more than 1,000 ancient documents were found in several places in Shanshan. Although they give little information about history, they are valuable sources for business and administration.

Two groups of ancient texts have been discovered in Shanshan: those in Chinese , written mainly by Chinese officials, and documents written in a north Indian Prakrit language in Kharosthi script. It could have been the native language of the Shanshan people. The Chinese used paper and silk as writing material; the Kharosthi documents, on the other hand, were mostly written on small, rectangular wooden tablets.

history

As in the other simultaneous kingdoms in the Tarim Basin, the time and circumstances of the origin of Shanshan are uncertain. Shanshan first appears in Chinese sources in connection with Emperor Han Wudi's western policy. At that time, the empire - like its easternmost city - still bore the name Loulan . Due to Loulan's relationship with the Xiongnu , political tensions arose with China, which the King of Loulan was initially able to avert from escalating. To ensure peace, both China and the Xiongnu took sons of the Loulan king hostage. After his death in 92 BC Both sons raised a claim to the throne, in this conflict the son who grew up with the Xiongnu was victorious. This eventually led to 77 BC. To escalate the conflict: China had the king Changgui / Angui murdered. Changgui's brother Weituqi, who grew up with the Chinese, was installed as king and the name of the empire was changed to Shanshan . Some researchers believe that this also involved relocating the capital. At Weituqi's request, a Chinese colony was set up in Yixun, possibly Miran, to ensure peace in Shanshan and was administered by a marshal or later a commanding officer. In 45 AD there was a conflict with the rising king Xian of Yarkant , who could inflict a severe defeat on Shanshan. According to the report of Hou Hanshu , however, after the temporary end of Chinese domination over the Tarim Basin, Shanshan expanded his territory considerably to the west in the further course of the 1st century AD by conquering Xiao Yuan , Niya, Ronglu and Qarqan.

From 73 AD, the famous Chinese general Ban Chao undertook several campaigns to recapture the Tarim Basin, and from the very beginning he succeeded in securing Chinese control over Shanshan. Troops were also stationed in Shanshan in the course of Ban Yong's campaign against Turfan in 123 AD. The dependence on China became particularly strong in the 3rd century when the Western Jin dynasty established a military base in the city of Loulan. Numerous official Chinese documents date from this period that demonstrate China's strong position in civil affairs as well, although the King of Shanshan remained sovereign. This time also represents the great heyday of Shanshan. However, the number of Chinese documents has decreased considerably since 300, the last document from 330 uses a date that was already out of date at this point in time, which could indicate Shanshan's isolation from China.

Shanshan reappears in Chinese sources in 441 when the Chinese expelled King Bilong, who then fled to Qarqan, which apparently no longer belonged to Shanshan. In 445 Shanshan was conquered by the northern Wei . From then on, Shanshan's political independence seems to have finally come to an end.

art

Like the entire culture of Shanshan, the art was deeply rooted in the Buddhist culture of Gandhara . Due to the spatial proximity to Europe and the Eurasian steppes, however, there are also influences from Hellenistic and Scythian art.

architecture

Both sacred and profane structures are known of buildings. Among the secular buildings, residential buildings made of air-dried mud bricks and various fortifications from Loulan should be mentioned.

The predominant type of sacred buildings on the southern Silk Road was the stupa . In Shanshan, most of the stupas had a multi-level, square base with a height of 2.5 to 8 meters. Above it rose a mostly cylindrical, sometimes octagonal, drum, the upper end of which was partly hemispherical, partly flatter or pointed. In contrast, in several shrines from Miran there are rather atypical stupas with round bases.

Murals

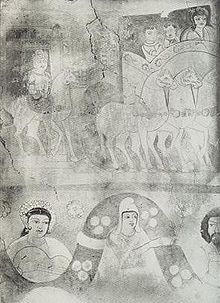

While there are good conservation conditions for wall paintings in the cave temples on the northern Silk Road, the location in Shanshan is much worse. The most important remains come from two round shrines in Miran (M III and MV). The frescoes from both shrines show great similarities in style, structure and motifs and can therefore be represented together.

The lowest frieze shows a garland decorated with flowers, which is carried by partly naked and partly clothed youthful figures. Her arches contain winged people in three-quarters perspective, but also different figures who differ in terms of gender, age, gestures and objects that they hold in their hands. A band separates the middle frieze, on which, as well as the top frieze, various, apparently mostly Buddhist scenes with people, animals and buildings can be seen.

The style of the paintings is very uniform: the faces are rounded, a little oblong and soft. The neck is thick and cylindrical, often shown with three horizontal folds. The eyes are wide open and large, but the noses are a bit short. The mouth is large and has a rounded, soft shape. The robes are smooth and show no folds. All in all, the style is very realistic, simple, plain and clear.

The paintings from M III and MV were painted in tempera on a stucco base made of clay and reeds. The contours are designed as a thick line, the surfaces were obviously not painted in part and therefore have the same color as the always monochrome background. Water was used to imitate shadows, but particularly light areas were then painted over with light paint.

Wood carvings

Wood carvings came to light in several residential and religious buildings in Niya and Loulan; among them there are both pieces of furniture and various parts of the building that have been decorated with carved reliefs. Popular motifs are various plants, for example lotus flowers or rosettes, and dragon-like, winged monsters whose presence can possibly be traced back to Scythian influence. Occasionally, architectural and purely geometric motifs also appear. A pair of chair legs from Niya and a wooden statuette from Loulan even show human figures.

textiles

Significant textile finds have been made in Niya and Loulan so far. Some textiles show clear references to other finds from the northern periphery of Han-period China. A man's silk jacket from Niya stands out among these pieces. It is richly decorated with regular patterns and Chinese lettering.

However, there are also textile remnants with a strong Hellenistic influence, including, for example, a wool fragment from Loulan showing Hermes with a caduceus , and a silk fragment from Niya made in batik technique (see picture on the left), on which there are various motifs: geometric patterns, a goddess, a dragon-like being, and human feet. The human figures show both Buddhist and Hellenistic influence, while the geometric elements show clear relationships with the murals from Miran and wood carvings from Niya.

economy

Due to the incomplete archaeological finds, the written sources are the main source for Shanshan's economy. The Chinese Hanshu writes in Chapter 96a:

- The land is sandy and salty, it has few fields, and it sources grain and agricultural products from neighboring countries. The country produces jade, lots of reeds, Chinese tamarisks, hutong trees, and white grass. The people go with their flocks and follow water and grass. It has donkeys, horses and lots of camels.

Although other sources suggest that Shanshan was arable, the economy was heavily based on cattle breeding. Due to the location on the Silk Road, participation in east-west trade was also possible, which is confirmed by finds of Chinese and Hellenistic-Roman goods. Chinese coins of the Wuzhu type and indigenous coins with Kharosthi inscription are evidenced by archaeological finds as a means of payment .

religion

Nothing is known about the original religion of Shanshan. Presumably since the 1st century AD, Buddhism was at least the predominant religion in Shanshan. This results not least from the countless Buddhist shrines and stupas as well as the Buddhist character of the works of art preserved. According to the report of the Chinese pilgrim Faxian , who visited Shanshan in AD 399, 4,000 Buddhist monks who followed Hinayana Buddhism lived here at that time . The center of the Buddhist community ( Sangha ) in Shanshan was in Kroraina / Loulan in the 3rd century.

Kings

The names and reigns of the kings of Shanshan can only be partially reconstructed, especially since the rulers known from Chinese sources are difficult to identify with names from Kharosthi texts.

At least the following kings are mentioned in Chinese sources:

| Pinyin | Chinese | Dating |

|---|---|---|

| Changgui / Angui | 嘗 歸 / 安 歸 | 92-77 BC Chr. |

| Weituqi | 尉 屠 耆 | from 77 BC Chr. |

| On | 安 | around 40 AD |

| Guang | 廣 | around AD 75 |

| You Huan | 尤 還 | around 123 AD |

| Yuan Meng | 元 孟 | around 330 AD |

| Xiumito | 休 密 馱 | around 383 AD |

| Bilong | 比 龍 | until 441 AD |

| Zhenda | 真 達 | C 441-445 |

In the Kharosthi texts from Shanshan, the following kings are mentioned (their order is not known):

- Tomgraka

- Tajaka

- Pepiya

- Amgvaka

- Mahiri

- Vasmana (= Yuan Meng?)

literature

- Folke Bergman : Archaeological Researches in Sinkiang. Especially the Lop-Nor region. (Reports: Publication 7), Stockholm 1939 [1]

- T. Burrow: A translation of the Kharosthi Documents from Chinese Turkestan. London 1940 [2]

- Sven Hedin : Scientific Results of a Journey in Central Asia 1899–1902 , 6 volumes of text + 2 volumes of maps, Stockholm 1904–7.

- Aurel Stein : Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China , 5 vols. Clarendon Press., London & Oxford 1921 [3]

- Aurel Stein Innermost Asia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia, Kan-su and Eastern Iran , 5 vols. Clarendon Press., London 1928 [4]

- Marylin M. Rhie: Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia (Handbook of Oriental Studies / Handbuch der Orientalistik - Part 4: China, 12, Vol. 1) (Handbook of Oriental Studies / Handbuch der Orientalistik) . Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 90-04-11201-4

- Marianne Yaldız : Archeology and Art History of Sino-Central Asia (Xinjiang). Handbook of Oriental Studies , Department 7, Volume 3, Section 2. Brill, Leiden 1987 ISBN 90-04-07877-0

- Yuri Bregel: An Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Brill, Leiden 2003. ISBN 90-04-12321-0