Sopilka

Sopilka ( Ukrainian сопілка ) is in the Ukraine played windway flute with traditional six to eight and a modern chromatic version ten finger holes. The sopilka , used nationwide in folk music ensembles , was originally played by shepherds; it is related to the dentsivka in western Ukraine, the dudka in Belarus and the sopel in Russia . Sopilka is also a general term for Ukrainian flutes , which also include short length flutes without a mouthpiece , which are known by various regional names.

Origin and Distribution

The oldest flute finds are bone flutes , which in Europe were apparently mostly blown through a core gap, while in Asia and on the American continent, notched flutes blown through the upper end predominated. As a melody instrument, the pan flute is likely to have preceded the flute with finger holes, since finger hole flutes with a musical tube represent a material saving with the same melodic possibilities and thus a further development compared to several pipes that produce only one sound ( single-tone flutes ).

For Siberia, engraved bird tube bones from the Neolithic Age , which presumably belonged to a panpipe, have been found in the area of Lake Baikal . They come from grave goods of the local Kitoi culture (2500–1500 BC). There are comparable finds from other prehistoric and early historical graves. The seven to eight tubular bones of a panpipe from a Neolithic burial ground near Mariupol in the Ukraine are particularly similar . It belonged to a hunting and fishing society from the end of the 3rd millennium BC. At ten centimeters in length, it sounded extremely high - as was customary for the Neolithic Age - and possibly produced notes of the five- and six-stroke octave .

Core gap flutes are known from Glaskowo in the Baikal region and other settlements of Neolithic hunters and fishermen in northern Asia. In southern Central Asia, terracotta statuettes with female musicians playing longitudinal flutes have been handed down since the middle of the 1st millennium. Flutes in this region are common under the name tulak or similar. From the early Middle Ages, spread over Eastern Europe culture of the Avars remained from tibias of cranes made double flute with five finger holes obtained as evidence of a potentially pentatonic be used music. A double beaked flute in today's Ukraine, which consists of two parallel music tubes drilled into a piece of wood, is the dvodentsivka . It is similar to the Slovak double flute dvojačka . The flute has either two melody tubes with four finger holes on the right and three finger holes on the left or a melody tube with five finger holes and a drone tube without finger holes next to it.

No transverse flutes are known from archaeological finds in Europe. Presumably coming from India, transverse flutes did not appear on illuminated manuscripts in the Byzantine Empire until the 10th century , from where they subsequently reached Europe. Significant early evidence of the existence of the flute is a mural in the 11th century St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev showing acrobats playing trumpets or shawms, lutes, psalteries and cymbals .

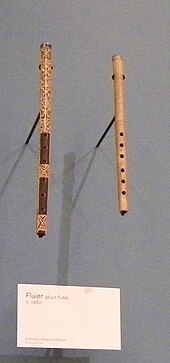

The most common type of flute in European folk music includes simple straight flutes made of soft twigs (hazelnut, elder, willow) or harder types of wood, which are also called shepherds flutes and have six finger holes. In Eastern Europe, this type includes the rim-blown fluier in Romania, the similar kaval in Bulgaria and the fulyrka flute in the southern Polish Carpathian Mountains . The floyara is a flute that is open on both sides and played in the Ukrainian Carpathians . The approximately 60 centimeters long floyara is a simple shepherd's flute with six finger holes, which are arranged in two groups of three.

The rare group of tongue duct flutes , which have a cutting edge, but not a recorder head, but an open end into which the tongue is inserted to narrow the opening to a wind tunnel, represents a kind of hybrid between end-edge flutes and core-gap flutes . This type of flute occurs among Finno-Ugric peoples (in Finland as mäntihuilu ), as well as in the East Slavic-speaking area : in the Ukraine with five to six finger holes under the name dudka . The word dudka (from Russian dut , "to blow", related to dudy and duda for bagpipes) also generally designates core gap flutes in Belarus, Russia and the Ukraine. To the regional names of these nuclear fission flutes include in Belarus pasvistsyol, svistsyol, sipovka and sapyolka , Russia svirer, pizhatka, sipovka and sopel and sopilka in Ukraine.

The sopilka is related to the schupelka (шупелка, šupelka ), a shepherd's flute with six finger holes that is open at both ends and is played in Macedonia and neighboring countries . The names for wind instruments, which also include sopila (plural sopile ) for a bowling oboe played on the Croatian island of Krk , go back to the Slavic root * sop , "to blow".

Design and style of play

In the older form, the sopilka has a 30 to 40 centimeter long, cylindrical play tube made of soft willow wood, hazelnut wood or elderberry with six finger holes. In self-made flutes, the finger holes are cut with a knife or burned out with a glowing iron. A wooden plug ( copyk ) with a rectangular wind tunnel is inserted at the top end that has just been cut off . The air flow is directed through the wind tunnel onto a blowing edge on the top of the tube. In the Carpathian Ukraine in the west of the country this flute is also called dentsivka .

The prepared from hazelnut sopilka the Huzuls with six finger holes produces the tones d-fis-A-H-c-d-e. An exercise instrument with five finger holes is known as a dentsivka by the Hutsulen . In addition to this type of flute, the Hutsuls use other flutes from the pastoral tradition, including the frilka , a short notched flute that is open at the end, and the floyar (k) a , a longer version of the frilka . With these flutes with an open top, also called sopilka , which are used in the folk music groups of Carpathian Ukraine, sound formation is more difficult than with flutes with a wind tunnel. The soft and deep sounding floyara is about one meter long and has six finger holes. It is usually played as a soloist, with the musician adding a deep hum with his voice.

The high-sounding frilka is an orchestral instrument that is used in different lengths according to its accompanying function. A 20 centimeter long frilka with the pitch of a piccolo is used for playing with a violin and a 30 centimeter long flute is suitable for the dulcimer cymbaly ( tsymbaly ). A 40 centimeter variant sounds lower.

A simple Ukrainian magnetic gap flute without finger holes is the 70 centimeter long telenka (теленка, also tylynka ), which also occurs among the Hutsuls and is related to the Romanian tilincă and the Slovak koncovka . By alternately opening and closing the lower opening with your finger and by overblowing , the player can create a range of overtones . In addition, the tones can be increased gradually by partially closing the lower end.

Another Ukrainian flute that occurs in the western Ukrainian mountains is the zubivka (зубівка, subiwka , also skosivka ). The mouthpiece of this approximately 60 centimeter long, fingerhole-free flute is cut diagonally at a 45-degree angle.

In the medieval sources up to the 13th century in Kiev , at that time the capital of the Kievan Rus , dancers and musicians are mentioned and depicted who played with the flute sopilka , the bowed bowl-neck lute gudok , the box zither gusli , the double-reed instrument zurna , the frame drum bubon (бубон ) and the pelvis tarelki occurred. During the Soviet period around 1960, four instruments were taught at the music schools and conservatory in Kiev for solo use and for use in folk music ensembles: the plucked instrument bandura , the zither gusli , the lute domra and the sopilka .

Among the instruments of today's Ukrainian folk music include not only the sopilka the long wooden trumpet trembita , violin ( Skrypka ), Bass ( basola , three-stringed viola da gamba ), dulcimer ( cymbaly ), bagpipes ( volnyka or koza, see. The Polish koza , on Huzuls dudka ) and jew's harp ( drymba ). The best known instrumental ensemble of folk music ( troista muzyka ), which is part of the dance accompaniment at weddings and other festive events, consists of violin, dulcimer and bass or frame drum; another ensemble performs with two violins, bass and flute.

Around 1970 flutes with ten finger holes were introduced - eight on the top and two thumb holes, which allow a chromatic sequence of notes. Since then, the sopilka can also be used in popular light music in addition to folk music. For example, the pop singer Ruslana Lyschytschko uses folk musical instruments, including a sopilka, in her song Kolomyjka (on CD Wild Dances, 2003) . The title refers to the Hutsul folk dance kolomyjka (plural kolomyjky ), whose melodic and rhythmic structure forms the musical basis. The sopilka follows the melody line of the singing voice.

The sopilka , originally played by shepherds and boys as a soloist for their own entertainment and with melodies typical of the region , was initially recorded by the Hutsuls in instrumental ensembles at the beginning of the 20th century and later integrated into Soviet folk music with all-Ukrainian narodni muzychny instrumenty ("national musical instruments"). As in pop music, the sopilka appears in films as a stereotype for Ukrainian country life, which otherwise includes colorful costumes, horse-drawn carts and zlydni (mischievous goblins from the field of folk tales).

literature

- Sopilka . In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments . Volume 4, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, pp. 557f

Web links

- Vladimir Sholohoff: Sopilka СОПІЛКА (Ukrainian ethnic flute). Introduction for beginners. Youtube Video (Ukrainian with English subtitles)

Individual evidence

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : A Survey of Musical Instruments. Harper & Row, New York 1975, p. 555

- ↑ Klaus P. Wachsmann : The primitive musical instruments. In: Anthony Baines (ed.): Musical instruments. The history of their development and forms. Prestel, Munich 1982, pp. 13–49, here p. 42

- ↑ FM Karomatov, VA Meškeris, TS Vyzgo: Central Asia. (Werner Bachmann (Hrsg.): Music history in pictures . Volume II: Music of antiquity. Delivery 9) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1987, p. 44

- ^ Albrecht Schneider: Archeology of Music in Europe . In: Timothy Rice, James Porter, Chris Goertzen (Eds.): The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music . Volume 8: Europe . Routledge, New York / London 2000, pp. 34–45, here p. 41

- ↑ Beate-Maria Pomberger, Nadezhda Kotova, Peter Stadler: Flutes of the first European farmers . In: Annals of the Natural History Museum in Vienna, Series A, Vol. 120, 2018, pp. 453–470, here p. 467

- ↑ FM Karomatov, VA Meškeris, TS Vyzgo, 1987, p. 96

- ↑ Samuel Szadeczky-Kardoss: The Avars. In: Denis Sinor (ed.): The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, pp. 206–228, here p. 228

- ↑ Dvodentsivka . In: Grove Music Online, May 25, 2016

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu, Howard Mayer Brown, Jaap Frank, Ardal Powell: Flute. I. General. 2. Classification and distribution. In: Grove Music Online, 2001

- ^ Roger Blench: The worldwide distribution of the transverse flute. Draft, October 15, 2009, p. 4

- ^ Andreas Michel, Oskár Elschek: Instruments of folk music . In: Doris Stockmann (Ed.): Folk and popular music in Europe. (New Handbook of Musicology, Volume 12) Laaber, Laaber 1992, p. 316

- ↑ Blowing device for the split tongue flute (Slovakia) . Illustration in: Oskár Elschek: Typological working methods for folk musical instruments. In: Studia instrumentorum musicae popularis I, Stockholm 1969, pp. 23-40

- ^ Ernst Emsheimer : Tongue Duct Flutes Corrections of an Error. In: The Galpin Society Journal , Vol. 34, March 1981, pp. 98-105, here pp. 100f

- ↑ Inna D. Nazina, Ihor Macijewski: Dudka . In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments . Volume 2, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 100

- ↑ Radmila Petrović: Šupelka. In: Grove Music Online, January 31, 2014

- ↑ Viktor Sostak: The Sopilka . carpatho-rusyn.org

- ↑ Nina Gerasymova-Persyds'ka, Onisja Schreer-Tkachenko: Kiev. II. The development of professional music up to the middle of the 13th century. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1996)

- ↑ Vanett Lawler: The Arts in the Educational Program in the Soviet Union . In: Music Educators Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, February – March 1961, pp. 40–48, here p. 46

- ↑ Nina Gerasymova-Persyds'ka: Ukraine. II. Folk music. In: MGG Online, November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1998)

- ^ Folk musical instruments. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ Sopilka. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine ( Encyclopedia of Ukraine, Vol. 4, 1993)

- ^ David-Emil Wickström: “Drive-Ethno-Dance” and “Hutzul Punk”: Ukrainian-Associated Popular Music and (Geo) politics in a Post-Soviet Context . In: Yearbook for Traditional Music, Vol. 40, 2008, pp. 60-88, here pp. 67f

- ^ William Noll: Ukraine. In: Thimothy Rice, James Porter, Chris Goertzen (Eds.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 8: Europe . Routledge, New York / London 2000, p. 816

- ^ Natalie Kononenko: The Politics of Innocence: Soviet and Post-Soviet Animation on Folklore topics. In: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 124, No. 494, Fall 2011, pp. 272-294, here pp. 288f