Stoic sage

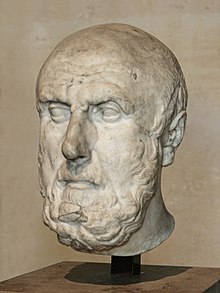

The stoic sage ( Greek σοφός , Latin sapiens ) is the ideal image of stoic ethics , which was first formulated by Chrysippus von Soli (3rd century BC).

Ancient philosophy

The wise man, then, lives perfectly in harmony with nature , identified with reason and at the same time with virtue , the supreme good of the Stoics. In all of his actions all four cardinal virtues are equally evident : wisdom , courage , temperance and justice . Therefore he has eudaimonia , the perfect bliss, for two reasons : First, he has recognized that the affects and desires are based solely on mental illnesses or errors. He is thus free from them and self-sufficient as an individual . Since affects and desires are always related to the body, some Stoics like Poseidonios (135–51 BC) and Epictetus (approx. 50–125) lead to a certain hostility towards the body and contempt for everything physical. Such a perfect person no longer has any needs, but it is useful to him to live in friendship with God , which consists of a consensus in judgment about good and bad.

On the other hand, it is said that it is clear to the wise that all pleasure and all displeasure are indifferent to the highest good, αδιάφορον adiaphoron . He can endure the vicissitudes of the stoically unchangeable and predetermined fate such as illness, poverty or social isolation with the proverbial stoic calm, the απάθεια apatheia ( dispassion ). At most “positive passions” such as friendliness, joy or love for his children are allowed to him. Even compassion , which means, so to speak, an infection with the negative affects of another, disturbs the calmness of the wise man and was therefore explicitly rejected. But that did not rule out that he helped those in need or gave alms . Even assuming responsibility in the political arena was considered compatible by some Stoics with the ideal of the wise. This is where the stoic ideal of the dispassionate sage differs from the Epicurean goal of ἀταραξία ataraxia (lack of confusion, which implies distance from socio-political events), with which it has much in common.

Cicero (106–43 BC) can therefore declare in his Tusculanae disputationes , which are based on stoic sources, that the sage is happy even after torture . The Greek philosopher Plutarch (45-ca. 125), who was critical of the Stoics, comes down with a formulation in which the paradoxical happiness of the wise is even more pointed:

“The stoic sage does not lose his freedom even in prison; you throw him down from the rock, he suffers no violence; you put him under torture, he suffers no torment; chop off his limbs, he remains unharmed; if he falls even while wrestling, he is undefeated; it is enclosed with walls, it is not subject to siege; if he is sold by the enemy, he is not a prisoner. "

The Stoics frankly admitted that a manifestation of this ideal in reality was extremely unlikely. In the case of Alexander von Aphrodisias , a third-century peripatetic , it is said that they considered a stoic sage to be “rarer than the phoenix ”. Nevertheless, the Stoics maintained that this ideal is the only way for a person to be happy. In its 46 BC Chr. Created paradoxes Stoicorum discussed the thesis Cicero, who was not a wise man, is necessarily a slave . The stoic philosopher Seneca (approx. 1-65) moved away from the overly rigorous demands of the old and middle Stoa and placed practical advice in the focus of his didactic writings. In one of his letters on questions of ethics , for example, he emphasizes that life becomes bearable if one has only begun to strive for wisdom. Nevertheless, he also uses the figure of the almost god-like perfect sage to show how desirable his properties are:

“Si hominem videris interritum periculis, intactum cupiditatibus, inter adversa felicem, in mediis tempestatibus placidum, ex superiore loco homines videntem, ex aequo deos, non subibit te veneratio eius? non dices, 'ista res maior est altiorque quam ut credi similis huic in quo est corpusculo possit'? "

"When you see a person not to be frightened by danger, untouched by desires, happy in misfortune, serene in the midst of stormy times, seeing people from a higher vantage point, the gods on the same level, won't you be in awe of him?"

In his treatise de beneficiis (On Beneficiaries ), Seneca defines the wise as someone to whom the whole world belongs, but who has no trouble keeping it in his possession. Like a god, he looks down on all of humanity as the most powerful and the best.

The Stoics were already sharply criticized for their utopian ideal of the sage in antiquity. Seneca itself allows, right after the definition from de beneficiis just quoted , to make fun of it: “derideas licet”. In particular, the anti-dogmatic-skeptical academics found a point of attack in the ideal of the sage. For example, in his theological work De natura deorum , Cicero has Gaius Aurelius Cotta as a representative of this school polemicize against the Stoics, who presented an all too improbable happiness as an ideal:

"Nam si stultitia consensu omnium philosophorum maius est malum, quam si omnia mala et fortunae et corporis ex altera parte ponantur, sapientiam autem nemo adsequitur, in summis malis omnes sumus, quibus vos optume consultum a dis inmortalibus dicitis."

“For if, according to the unanimous judgment of all philosophers, ignorance is a greater evil than all of its confronted strokes of fate and physical suffering combined, but no one can attain true wisdom , then we are all in the greatest misery, we, for whom, according to your assertion, the immortal gods have taken care of the best. "

The poet Horace (65–8 BC), who had been an Epicurean in his youth, still poured in his in the year 20 BC. Published the first epistle biting mockery of the Stoics and their wise men, who, like Jupiter, was rich, free, honored, beautiful and above all healthy - unless he was tormented by a cold .

reception

Antiquity

In antiquity, eminent men were often stylized as stoic sages through the depiction of their death: The authors then attach great importance to showing that their hero approached death courageously and with dignity and remained master of his emotions to the end. Examples are Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis , as Lucan depicts him in his Pharsalia : free of affects, purely obeying reason, full of love for the state and its fellow men and at the same time happy, the description of Seneca's forced suicide in the annals of Tacitus or the heroization of Death of Pliny the Elder at the eruption of Vesuvius 79 by his nephew . In the Bible, science is on parallels between the description of the Stoic sage and the sanctity ideal of the early Christians made. In his second letter to the Corinthians, written around 56, the apostle Paul describes his own paradoxical situation in distress and weakness with simultaneous glory and confidence:

“We are cornered from all sides and still find space; we neither know nor in and yet we do not despair; we are rushed but not abandoned; we are struck down and yet not destroyed. Wherever we go, we always carry the suffering of Jesus on our body so that the life of Jesus can also be seen in our body. "

Thus at least an indirect influence by the Stoic philosophy is obvious.

Modern times

Despite the strong reception of Stoic ethics since the Renaissance , the ideal of the sage did not play a significant role in modern philosophy. Arthur Schopenhauer derided in 1819 in his work The World as Will and Idea :

“The Stoic Wise [could] never gain life or inner poetic truth in their [the Stoic] portrayal […], but [remains] a wooden, stiff limbed man […], with whom one cannot do anything, not himself knows what to do with his wisdom, whose perfect calm, contentment, happiness contradicts the essence of humanity and does not allow us to get a clear idea of it. "

Today the ideal of the stoic sage is criticized as structurally inhumane: the stoic sage will, for example, save a child from a burning house, but not for the child's sake, but to do what is right himself; should his attempt at rescue fail and the child die, the stoic wise man would feel no regret, since he would be eo ipso free from disturbing affects, since, secondly, death is no evil for the child either, and thirdly, the death of the providential child would be induced to be identical with the divine Logos ruling the world .

literature

- M. Andrew Holowchak: The Stoics. A Guide for the Perplexed. Continuum International, 2008.

- Dirk Obbink : The Stoic Sage in the Cosmic City. In: Katerian Ierodiakonu (Ed.): Topics in Stoic Philosophy. Clarendon, Oxford 1999, pp. 178-127.

- Max Pohlenz : The Stoa. History of a Spiritual Movement . 2 volumes, 4th edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1970, ISBN 3-525-25711-2 , ISBN 3-525-25712-0 .

proof

- ↑ RW Sharples: Stoics, Epicureans and Skeptics. An Introduction to Hellenistic Philosophy. Routledge, New York 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Carl-Friederich Geyer: Introduction to the philosophy of antiquity. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1978, pp. 98ff.

- ↑ M. Andrew Holowchak: The Stoics, A Guide for the Perplexed. Continuum International, 2008 p. 19-25

- ↑ Willy Hochkeppel: Was Epicurus an Epicurean? Current wisdom teachings of antiquity. dtv, Munich 1984, p. 172.

- ↑ Jula Wildberger: Seneca and the Stoa: The place of man in the world. Volume 1: Text. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2006, ISBN 978-3-11-091563-1 , p. 267 f. (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Amelie Oksenberg Rorty: Appeasing the stoic passions. The two faces of individuality. In: Barbara Guckes (Ed.): On the ethics of the older Stoa. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, p. 166.

- ↑ Christoph Halbig: The stoic doctrine of affect. In: Barbara Guckes (Ed.): On the ethics of the older Stoa. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, p. 66 f.

- ↑ Peter Scholz: The philosopher and politics. The development of the philosophical way of life and the development of the relationship between philosophy and politics in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC Chr. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, p. 349f.

- ^ Carl-Friederich Geyer: Introduction to the philosophy of antiquity. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1978, p. 104.

- ↑ Tusc. V, 73; Epicurus , Malte Hossenfelder: The Philosophy of Antiquity , had also represented this thesis . Volume 3: Stoa, Epicureanism and Skepticism. 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 1985, p. 116.

- ↑ Plutarch: From the rest of the mind and other philosophical writings. ed. and over. by Bruno Snell. Artemis, Zurich 1948, p. 75.

- ↑ Alex. Aph., 61N

- ↑ Ep. 16, 1; L. Annaeus Seneca: Philosophical writings. ed. and over. by Manfred Rosenbach. Volume 3, 4th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 122.

- ↑ Ep. 41, 4; L. Annaeus Seneca: Philosophical writings. ed. and over. by Manfred Rosenbach. Volume 3, 4th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 327.

- ^ "Unus est sapiens, cuius omnia sunt nec ex difficili tuenda. … Omne humanum genus potentissimus eius optimusque infra se videt. “Benef. VII, 3.2. L. Annaeus Seneca: Philosophical writings. ed. and over. by Manfred Rosenbach. Volume 5, 4th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 532.

- ↑ Benef. VII, 3.3. L. Annaeus Seneca: Philosophical writings. ed. and over. by Manfred Rosenbach. Volume 5, 4th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 532.

- ↑ Nat. III, 79; M. Tullii Ciceronis: De natura deorum , libri III. Of the nature of the gods. Three books. Latin-German, ed., trans. u. ext. v. Wolfgang Gerlach and Karl Bayer. Heimeran Verlag, Munich 1978, p. 441.

- ↑ ep. I, 1, V. 106-108; Marcía L. Colish: The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Stoicism in Classical Latin Literature. Brill, Leiden 1990, p. 180.

- ↑ Jan Radicke: Lucan's poetic technique. Studies on the historical epic. (= Mnemosyne Supplement. 249). Brill, Leiden 2004, pp. 140-151.

- ^ Bernhard Zimmermann: The death of the philosopher Seneca. Stoic probatio in literature, art and music. In: Barbara Neymeyr , Jochen Schmidt , Bernhard Zimmermann : Stoicism in European Philosophy, Literature, Art, and Politics. A Cultural History from Antiquity to Modernity. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, pp. 393–424.

- ^ Eckard Lefèvre: Pliny Studies VI. The great and the little Pliny. The Vesuvius letters (6.16; 6.20). In: Gymnasium. 103 (1996), p. 200.

- ↑ 2 Cor 4 : 8-10 EU

- ↑ Wolfgang Schrage: Theology of the Cross and Ethics in the New Testament. Collected Studies. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, p. 29f.

- ↑ Arthur Schopenhauer: The world as will and idea. ( Memento of March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Digital Library Volume 2: Philosophy, Volume 2, p. 215. (PDF file; 11.44 MB)

- ^ AA Long: Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Skceptics. Paperback edition. University of California Press, Los Angeles 1986, pp. 197f.