Apatheia

Apatheia ( ancient Greek ἀπάθεια apátheia "insensitivity, dispassion ", Latin impassibilitas ) was the term in ancient philosophy for a stable, equanimity and peaceful state of mind, which was closely connected with ataraxia , the imperturbability aimed at by the philosophers. Persistent practicing of dispassion was recommended to permanently prevent emotional shocks.

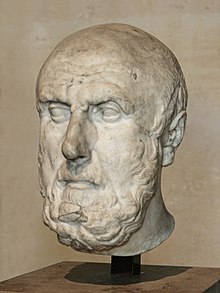

In the ethical literature , apatheia has been treated within the framework of the theory of affects . It was widely considered to be worth striving for, since it was hoped for relief from disturbing, painful and irrational affects such as fear or anger. The permanent calming of the mind was regarded as the basis of eudaimonia , the spiritual balance advertised as the ideal of life. The debates revolved around the question of the extent to which it is possible and desirable to erase passions without losing specifically human qualities through insensibility. Opinions differed widely about this. The most famous proponents of Apatheia were the Stoics , among whom Chrysippus of Soloi stood out with his pioneering affect theory. Her rigorous struggle against passions, however, met with opposition in other philosophy schools. As an alternative, critics of the Apatheia ideal recommended the mastery of passions, which are ineradicable as part of human nature.

Christian theologians adopted the philosophical concept of Apatheia and adapted it to their needs. A special topic was the apatheia of God, which was postulated because of the immutability ascribed to him, but which was difficult to reconcile with biblical statements about God's affects.

Ancient philosophy

Human apatheia

Definition

In the ancient Greek language, the term apatheia generally denotes the property of a thing or a person not to be subject to any external influence. In the case of people, it is meant that (undesired) emotional movements and states of mind ( páthē , singular páthos ) do not occur as reactions to external stimuli. Sensory perception no longer induces arousal in the mind of one who has attained apatheia. Therefore he is dispassionate, needless and self-sufficient. Longing and desire (epithymía) are as alien to him as fear.

In a broader sense, Apatheia means the absence of all affects, including the pleasant ones that are usually considered desirable. Often, however, the term apatheia is used in a narrower sense in ancient literature, according to which only or primarily negative, undesirable emotions are missing. Accordingly, positive excitations (eupátheiai) like joy are compatible with apatheia. In philosophical texts, the term apátheia usually denotes the freedom from suffering and destructive affects such as anger, fear, envy and hatred.

The controversial Apatheia ideal

Antisthenes , a prominent philosopher of the Greek classical period , regarded Apatheia as a worth striving for, taking the legendary self-control of his teacher Socrates as a model. This attitude was an important part of his ethical concept, which formed the starting point for the emergence of Cynicism . For Antisthenes, apatheia particularly included freedom from any pursuit of lust that goes beyond the elementary satisfaction of needs. He is said to have remarked: "I should rather be overcome by madness than pleasure."

Later, in the age of Hellenism , the Stoics, who also followed on from the Socratic tradition, took over the demand for affect overcoming and made it a central part of their teaching. Liberation from the tyranny of instincts and affects should enable serenity and peace of mind as well as rational action. Disapproved affects included compassion and remorse, as they cause distress, which is unacceptable to a stoic sage . Because pity and envy are causes of grief, they were placed on the same level.

The Stoics' apatheia ideal was not purely negative, it was not limited to the mere absence of undesirable states of mind. Rather, the desired mental state was positively determined as a highly desirable constant posture (Greek héxis ) of equanimity. So the term apatheia and ataraxia overlapped. Apatheia was not viewed as an individual virtue, but as a disposition which forms the basis for a virtuous and rational life.

As a way to achieve the desired state, the Stoics recommended habituation: one should get used to refusing to “consent” to passively received ideas, which are the prerequisite for passionate excitement. Behind this was the stoic conviction that in the human soul - as the Platonists believed - irrational areas do not have a life of their own. Rather, according to the Stoic understanding, the soul forms an organic unit, and its “parts” only have a functional character. They are instruments of the leading central authority (hēgemonikón) , which is located in the heart and organizes all mental and physical activities. This instance, the vital center of man, is rational by nature. She decides whether to give her consent to a performance (Greek synkatáthesis , Latin assensio ). If the idea is wrong, it can only gain approval because of an intellectual error, and then an affect such as dismay, confusion, or dejection arises. Thus affects can be avoided by following reason and seeing through and rejecting false ideas before they can trigger an affect. So does the wise man. In this stoic system the irrational is stripped of its particularity and incomprehensibility. It becomes explainable and completely intellectualized. In this context, the assertion that one can neutralize unwanted drives and emotions through knowledge and an act of will becomes conclusive.

Perfect apatheia was regarded as the hallmark of the stoic sage; the Stoics were convinced that it was reserved for him only. The Stoic Marcus Aurelius described the ideal of such wisdom with the words: “To be like the cliff on which the waves constantly break. But she stands unshaken and the surf calms down around her. "

The liberation from undesirable affects was mainly placed in the foreground by the Cynics and Stoics, but the other schools of philosophy also basically agreed that this was an important task, because ataraxia was a good for everyone - also and especially for the Epicureans of the highest order. The Neoplatonists , who set great store by purification of the mind and advocated asceticism , believed that apatheia, as freedom from passions, was the natural state of the philosopher's soul redeemed from ignorance. Those who cannot realize this ideal should at least try to curb the affective impulses.

The megaric Stilpon took a radical position, who held similar views on ethics as the Stoics and Apatheia even considered the highest good. He is said to have been of the opinion that the wise man not only remains unaffected by the affects, but does not even feel them.

The Roman poet Horace , who was strongly influenced by the Epicurean doctrine, found a classic formulation for the ideal of the superior man in the well-known verses:

Si fractus inlabatur orbis,

inpavidum ferient ruinae.

Even if the world falls apart,

the rubble will hit a fearless one.

It was disputed how far one should go in liberation from the affects and whether dispassion is at all possible and natural. Plato called for the rule of reason over those parts of the soul driven by passions, but rejected a life that contains insight, reason, science and memory, but neither pleasure nor displeasure. He stated that no one considered desirable a life that was "totally devoid of sensation (apathḗs) in any way ." Whoever chooses such a way of life is choosing something contrary to nature, either out of ignorance or obeying an unfortunate compulsion. In the Platonic Academy , the philosopher Krantor von Soloi in particular turned against a radical demand for Apatheia. In his work On Mourning, he was convinced that the bereaved for a deceased person's mourning was natural and should therefore be allowed. Only excessive and therefore unnatural affects should be suppressed. Indolence is not compatible with human nature and leads to destruction. Against the accessibility of Apatheia it was argued that the feeling of suffering (Greek páthē ) is natural and therefore a complete liberation from it is illusory. The thesis that dispassion is worth striving for was countered that affects contribute to the attainment of virtue and that their eradication affects the ability to act virtuously.

Compensating positions

The peripatetics admitted to the generally recognized goal of affect control, but rejected the stoic idea that perfect apatheia is achievable and worth striving for. They followed the teaching of their school founder Aristotle , according to which affects should not be exterminated, but only brought to the right level. This is to be achieved by keeping the “middle” ( mesotes ) between two undesirable extremes - a deficiency and an excess. This concept is called metriopathy (moderation of passions), which the peripatetics themselves did not use. They did not mean a moderation in the sense of general dampening and weakening of the affects, but only the measure appropriate to the respective situation. In doing so, they did not rule out strong affects. The Platonists also represented an ideal of moderation. In contrast to the peripatetics, however, they did not regard keeping the right middle between two extremes as a virtue, but instead demanded that a certain individual passion be limited to the appropriate level.

The New Pythagoreans also rejected the destruction of affects. They believed that the able could no more be free from displeasure than the body from illness and pain. One should not ask anything of man that exceeds his nature. The affects are useful, because without them the soul would be sluggish, would no longer have any drive for beauty and would no longer feel any enthusiasm. If one completely expelled the emotions, one would destroy the virtue for which it is essential. With the demand of moderation, the New Pythagoreans followed the Peripatetic and Platonic view.

In spreading their doctrine, the Stoics had to deal with the charge that the stoic sage was hard and callous. In order not to make the harsh demand for freedom from affect appear unworldly and contrary to nature, some of them found themselves ready to moderate it. In this sense it was expressed as early as the 3rd century BC. Chr. Chrysippus , a key spokesman of the Stoa. Although he rejected most of the emotions, he approved of some, especially the joy of the wise man who “approves” of such an emotion when he has recognized its justification in the given situation. According to Chrysippus' teaching, only the stoic wise man is capable of doing this, since only he has the necessary power of judgment. In the 2nd century BC The Stoic Panaitios , who endeavored to develop the doctrine further, gave up the goal of apatheia and accepted the affects as realities of human nature, the right control of which is the task of the philosopher. Poseidonios took a similar position.

The Stoic view of the world found considerable approval in the Roman upper class, but the devaluation of affects met with opposition. So Cicero turned against an exaggerated apatheia. He asserted that numbness was inhuman because man was not made of stone. The Roman stoic Seneca responded to such objections in the 1st century . He tried to rob the stoic ethics of the impression of inhuman hardship and repulsive coldness. Seneca believed that the appearance of affects and the involuntary being moved by them could not be completely avoided. A residual sensation, a “shadow” of the affect, is also retained in the wise man. According to Seneca's remarks, this includes blushing, a touch of fear in a seemingly dangerous situation or tears in bereavement. Seneca viewed such phenomena as physical consequences of the triggering event, quasi mechanical changes, for which the person concerned cannot help. With regard to their avoidability, his assessment varied. In any case, he was of the conviction that it was possible for the stoic wise man not to grant the affects any power over himself and not to let them determine his self-perception and his actions. The influential Stoic Epictetus later expressed himself in this sense . Such considerations were already developed in Hellenistic times. They are based on the idea that impulses like hunger and thirst, pleasure and pain are natural processes. They only become moments of human feeling, striving, and action when the person takes a position on them, by granting or refusing consent. According to this, Apatheia does not mean freedom from physical pain as a physical effect, but from the mental pain that this effect triggers if one agrees to it. According to this understanding, man is fully responsible for his affects.

The writer and moral philosopher Plutarch took an ambivalent stance . As a Platonist, he advocated caution and moderation in dealing with passions. He polemicized against Stoic ethics and asserted in this connection that a complete eradication of the emotions was neither possible nor desirable. He took this view with regard to the technical terminology of stoic apatheia. In some of his works, however, he used the term in a general linguistic sense with positive connotations or drew attention to the ambivalence of insensitivity: What appears on the outside as admirable self-control, according to Plutarch's account, can also be due to a problematic lack of empathy or even to inhuman insensitivity .

Divine Apatheia

Apatheia was considered an important feature of world-ruling power from an early age. The pre-Socratic Anaxagoras called the nous , the all- ruling principle, as apathḗs , that is, as that which cannot be affected. The Nous des Anaxagoras is the authority that initiates all processes and is itself not influenced by anything. Aristotle, who agreed with Anaxagoras, characterized the divine “first immobile mover” as immutable and expressly ascribed Apatheia to him.

In philosophical circles the conviction was widespread that a god has no needs and that there can be nothing that is desirable for him or that bothers him. From this idea of divine self-sufficiency went in the 2nd century BC. BC the skeptical Platonist Karneades when he formulated the problem of divine Apatheia. His train of thought is: Every living being apart from plants as such necessarily has a sensitivity for what is beneficial and harmful. This is a characteristic of life and therefore also applies to a God who is understood as a living being. But when a god feels something pleasant or unpleasant, he likes or dislikes it. Thereby a change occurs in him. Thus it can be influenced from the outside in a positive or negative sense. If he does not like something, he suffers a change for the worse. So he is not absolutely impervious to bad influences. But deterioration means decay and impermanence. Immutability and immortality, however, are defining characteristics of a god. Thus God cannot be both alive and eternal. Hence the idea that there is an eternal and living deity is inherently contradictory.

Judaism and Christianity

Human apatheia

The Jewish philosopher and theologian Philon of Alexandria adopted the Apatheia ideal from the Stoic tradition . For him, the liberation from harmful affects, to which he also counted pleasurable, but from his point of view sinful emotions, or at least their restraint was a religious duty. He considered all actions to be reprehensible which are brought about by fear, sadness, desire for lust or other impulses of this kind. Philo claimed that Apatheia led to perfect bliss. However, he did not mean complete numbness. He found some emotions helpful, and unlike the Stoics, he accepted pity as a legitimate emotion. He believed that Apatheia had to be achieved by fighting the affects, but that divine help was also required.

The term apatheia does not appear in either the Septuagint , the Greek Old Testament , or the New Testament . However, it was used by numerous eastern church fathers such as Clement of Alexandria , Origen , Athanasios , Basilios and Gregory of Nyssa . They propagated Apatheia as a moral ideal.

Euagrios Pontikos , an influential " desert father " of the 4th century, particularly insisted on the elimination of all influences of impulses of passion on the mind. He took over the stoic term in full and expanded it to include Christian aspects. He regarded the complete detachment from the emotional effects of the sensory impressions as a prerequisite for a pure prayer, which should be performed with complete emotional and intellectual imperturbability. Euagrios made apatheia as an ethical norm a core part of his teaching. He called her the gatekeeper of the heart. According to his definition, it is "a calm state of the rational soul consisting of gentleness and prudence". Among other things, Euagrios criticized the passions for the fact that, as he believed, they obscure the capacity for knowledge and dull and deform the intellect . Thanks to Apatheia, one can concentrate on the essentials and arrive at the right judgments.

The Church Fathers who stood up for Apatheia were very influential in monastic circles. Her concept of dispassion was met with approval. From the 390s onwards, the Greek Historia monachorum in Aegypto , which Rufinus of Aquileia translated into Latin around 403 , made a significant contribution to its dissemination . In late antiquity and in the Middle Ages, this work was one of the most famous Greek hagiographic writings. In this way the Apatheia ideal acquired an important role in monastic asceticism in the East. The Christian authors, however, did not usually advocate the most radical variant, according to which all affects are only disturbances, but rather in more or less moderate versions. The influential writer Johannes Cassianus , a pupil of Euagrios Pontikos, contributed to conveying such ideas to the West. In his Latin works he reproduced the Greek expression Apatheia with puritas cordis (purity of the heart) in order to make the anti-affect attitude in the Western Roman Empire attractive through a positive formulation.

The Latin-speaking Church Fathers, whose world of thought shaped the teaching of the Western Church, tended to evaluate the affects more positively than the Greek-speaking Easterners. Augustine and Jerome in particular largely rejected the ideal of Apatheia (Latin impassibilitas ). As a justification for his negative attitude, Augustine cited that Christ was angry and wept and that the apostle Paul was exposed to violent emotions. He also put forward the argument, among other things, that believers should have a fear of hell . Laktanz vigorously polemicized against the stoic plan to destroy passions. He found that only a madman could set himself the goal of depriving man of the affects that were part of his nature.

Michel Foucault pointed out a fundamental difference between pagan and Christian apatheia. The non-Christian philosopher wants to free himself from undesirable passions so that he no longer has to suffer their effects; that is, he wants to escape passivity, being at the mercy of being at the mercy, and as the master of his mind, take on the most active role possible. His goal is mastery of fate and freedom from suffering. The Christian ascetic, on the other hand, does not fundamentally reject suffering. He does not want to be master, but to submit and become obedient. As part of his ideal of obedience, he takes action against his selfish self-will, which is expressed in the affects. He strives for Apatheia in the sense of destroying self-will. In contrast to the pagan philosopher, he does not want to become more active, but more passive.

Apatheia of God

In Christian theology, the concept of apatheia posed a problem with regard to the understanding of God. In principle, it was about the dilemma already recognized by Karneades. On the one hand, the idea of God's eternal perfection and bliss seemed to preclude him from being subject to changing affective states; on the other hand, the suffering of Christ and the fact that anger and zeal are attributed to God in the Bible suggested that there were emotions of God that are difficult to reconcile with Apatheia. The Fathers of the Church decided in accordance with the Greek philosophical traditions for the answer that the unrest and changeability associated with affects are out of the question for God, therefore an apatheia of God can be assumed. Occasionally, however - for example in Ignatios of Antioch and Origen - individual contradicting statements can also be found without the contradiction being resolved.

The Jew Philon of Alexandria came to the same conclusion as the Church Fathers, who explained the statements of the Tanakh about an angry and jealous God as adaptations to the limited capacity of ordinary people. He believed that God could not be influenced and was particularly opposed to the idea that God could repent of a decision. On the other hand, however, he accepted the assumption of God's compassion, so he did not start from an absolute lack of affect of God.

The followers of docetism found a radical solution to the suffering of Christ . They taught that Christ only apparently had a human body and therefore only apparently suffered. In doing so, they preserved the concept of divine apatheia. The supporters of Patripassianism took the opposite position . They emphasized the oneness of God and criticized the doctrine of the Trinity . From the principle of the oneness of God, they concluded that not only Christ but also God the Father suffered at the crucifixion. The church father Ignatius of Antioch, who fought against docetism, tried to solve the problem by teaching that although Christ had suffered as a human being during his earthly life, since his death or since the resurrection, apatheia belonged to him as god. However, this approach created a new problem of the relationship between God and humanity in Christ that remained unsolved.

For the Christian Gnostics , the apatheia of God was a matter of course, although the Valentinians allowed an exception for pity. Since the Gnostics, in contrast to the great church theologians, separated the divine and the human part in Christ, they were able to defuse the christological problem by limiting the affectivity to the human part. Some Gnostics chose the docetistic approach.

Kant

Immanuel Kant took up the stoic term apatheia when he presented his concept of "moral apathy" in his book Die Metaphysik der Sitten , published in 1797 . He stated there that “apathy” had been viewed as “callousness” and subjective indifference and therefore fell into disrepute as weakness. To prevent such misinterpretation, Kant introduced the concept of moral apathy. This is to be distinguished from apathy in the sense of indifference . It is a strength and a necessary condition of virtue. According to Kant's definition, moral apathy is given when the feelings arising from sensual impressions lose their influence on the moral feeling only because “respect for the law becomes more powerful overall”. What is meant is an affect and passion free state of the mind in morally relevant situations. The “law” here means the “practical law”. In Kant's terminology, this is the principle that makes certain actions mandatory.

In the book Anthropology in a pragmatic way , which Kant published in 1798, he defined the principle of apathy, which is "a very correct and sublime moral principle of the Stoic school", as freedom from the affect that blinds and, viewed in isolation, always becomes unwise lead. The affect makes "itself incapable of pursuing its own purpose". A natural apathy is to be viewed with sufficient strength of soul as happy phlegm in the moral sense, since such a disposition makes it easier to become wise. In the Critique of Judgment , published in 1790, Kant wrote that apathy as the lack of affect of a mind that emphatically follows its unchangeable principles is far more exalted than the "brave" affect enthusiasm directed towards good , because such apathy has "the pleasure of pure reason" an affect could never deserve on their side. Only such a disposition should be considered noble.

literature

Overview representations in manuals

- Hans Reiner , Max-Paul Engelmeier : Apathy . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy . Volume 1, Schwabe, Basel 1971, Col. 429-433

- Pierre de Labriolle: Apatheia. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 1, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1950, Col. 484-487.

Investigations

- Herbert Frohnhofen : Apatheia tou theou. About the lack of affect of God in ancient Greece and among the Greek-speaking church fathers to Gregorios Thaumaturgos. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1987, ISBN 3-8204-1103-8 .

- Richard Sorabji : Emotion and Peace of Mind. From Stoic Agitation to Christian Temptation. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, ISBN 0-19-925660-8

- Michel Spanneut : Apatheia ancienne, apatheia chrétienne, I ère partie: L'apatheia ancienne . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World , Part II, Volume 36/7, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-11-001885-3 , pp. 4641–4717.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ See Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou , Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 30–37, 49.

- ↑ Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou , Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 38-41; Hans Reiner, Max-Paul Engelmeier: Apathy . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 1, Basel 1971, Sp. 429–433, here: 429–431.

- ↑ Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé: L'ascèse cynique , Paris 1986, pp. 146-148; Klaus Döring : Socrates, the Socratics and the traditions they founded . In: Klaus Döring among others: Sophistik, Sokrates, Sokratik, Mathematik, Medizin (= Hellmut Flashar (Ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1), Basel 1998, pp. 139–364, here: 276 f.

- ↑ Michel Spanneut: Apatheia ancienne, apatheia chrétienne, I ère partie: L'apatheia ancienne . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World , Part II, Volume 36/7, Berlin 1994, pp. 4641–4717, here: 4658 f., 4684.

- ↑ Michel Spanneut: Apatheia ancienne, apatheia chrétienne, I ère partie: L'apatheia ancienne . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Part II Volume 36/7, Berlin 1994, pp. 4641-4717, here: 4657 f.

- ↑ See for practicing habit Pierre Hadot: Philosophy as a form of life , 2nd edition, Berlin 1991, pp. 15-20. See Richard Sorabji: Emotion and Peace of Mind , Oxford 2000, p. 45 f.

- ↑ Maximilian Forschner : Die stoische Ethik , Stuttgart 1981, p. 59 f .; Peter Steinmetz : The Stoa . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 4/2, Basel 1994, pp. 491–716, here: 545–549.

- ↑ Mark Aurel, Self- Contemplations 4.49.

- ↑ On the Neoplatonic perspective, see the compilation of sources in English translation in Richard Sorabji: The Philosophy of the Commentators, 200–600 AD , Volume 1, London 2004, pp. 280–293. See Pierre Miquel: Lexique du désert , Bégrolles-en-Mauges 1986, p. 118 (on Plotin ).

- ↑ Michel Spanneut: Apatheia ancienne, apatheia chrétienne, I ère partie: L'apatheia ancienne . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Part II Volume 36/7, Berlin 1994, pp. 4641-4717, here: 4663.

- ↑ Horace, Carmina 3,3,7 f.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 21d-e, 22b. Cf. Dorothea Frede : Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 179 f.

- ↑ Hans Krämer : The late phase of the older academy . In: Outline of the History of Philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 3, ed. by Hellmut Flashar , 2nd edition, Basel 2004, pp. 113–129, here: 125.

- ^ Paul Moraux : Aristotelianism among the Greeks, Volume 2, Berlin 1984, p. 663.

- ↑ On the position of Aristotle see Richard Sorabji: Emotion and Peace of Mind , Oxford 2000, p. 194 f.

- ^ Francesco Becchi: Apatheia e metriopatheia in Plutarco. In: Angelo Casanova (ed.): Plutarco e l'età ellenistica , Florence 2005, pp. 385–400, here: 393–395; Marion Clausen: apatheia . In: Christoph Horn , Christof Rapp (Hrsg.): Dictionary of ancient philosophy , 2nd, revised edition, Munich 2008, p. 48 f.

- ^ Paul Moraux: Aristotelianism among the Greeks, Volume 2, Berlin 1984, p. 663 f.

- ↑ Richard Sorabji: Emotion and Peace of Mind , Oxford 2000, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ Peter Steinmetz: The Stoa . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 4/2, Basel 1994, pp. 491–716, here: 659, 692.

- ↑ Cicero, Tusculanae disputationes 3,6 (12); see. Lucullus 135.

- ↑ Uwe Dietsche: Strategy and Philosophy at Seneca , Berlin 2014, pp. 242-251.

- ↑ See Margaret E. Graver: Stoicism and Emotion , Chicago / London 2007, pp. 85–88.

- ↑ Maximilian Forschner: Die stoische Ethik , Stuttgart 1981, p. 135 f.

- ^ John Dillon : Plutarch the Philosopher and Plutarch the Historian on Apatheia. In: Jan Opsomer et al. (Ed.): A Versatile Gentleman , Leuven 2016, pp. 9–15. Cf. Francesco Becchi: Apatheia e metriopatheia in Plutarco. In: Angelo Casanova (ed.): Plutarco e l'età ellenistica , Florence 2005, pp. 385-400.

- ↑ Georg Rechenauer : Anaxagoras. In: Hellmut Flashar et al. (Ed.): Early Greek Philosophy (= Outline of the History of Philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity. Volume 1), Half Volume 2, Basel 2013, pp. 740–796, here: 773–775.

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics 1073a11 f.

- ↑ Harald Thorsrud: Ancient Skepticism , Stocksfield 2009, p. 61; Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou , Frankfurt am Main 1987, p. 85 f.

- ↑ Pierre Miquel: Lexique du désert , Bégrolles-en-Mauges 1986, p. 117 f.

- ↑ Richard Sorabji: Emotion and Peace of Mind , Oxford 2000, p. 385 f.

- ↑ Walther Völker: Progress and Perfection in Philo von Alexandrien , Leipzig 1938, pp. 126-134.

- ↑ See on Origenes Róbert Somos: Origen, Evagrius Ponticus and the Ideal of Impassibility. In: Wolfgang A. Bienert , Uwe Kühneweg (eds.): Origeniana Septima , Leuven 1999, pp. 365-373.

- ↑ Pierre de Labriolle: Apatheia. In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christianentum , Volume 1, Stuttgart 1950, Sp. 484–487, here: 485 f .; Pierre Miquel: Lexique du désert , Bégrolles-en-Mauges 1986, pp. 119–128.

- ^ Andrew Cain: The Greek Historia monachorum in Aegypto , Oxford 2016, pp. 252 f.

- ↑ Barbara Maier: Apatheia with the Stoics and Akedia with Evagrios Pontikos - an ideal and the other side of its reality. In: Oriens Christianus 78, 1994, pp. 230-249, here: 232, 238.

- ↑ Barbara Maier: Apatheia with the Stoics and Akedia with Evagrios Pontikos - an ideal and the other side of its reality. In: Oriens Christianus 78, 1994, pp. 230-249, here: 238-241.

- ↑ Andrew Cain: The Greek Historia monachorum in Aegypto , Oxford 2016, pp. 1 f., 252 f., 259, 267 f.

- ^ Andrew Cain: The Greek Historia monachorum in Aegypto , Oxford 2016, p. 269; Joseph H. Nguyen: Apatheia in the Christian Tradition , Eugene 2018, pp. 19-29.

- ↑ Pierre de Labriolle: Apatheia. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity. Volume 1, Stuttgart 1950, Col. 484-487, here: 486; Paul Wilpert: Ataraxia . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity. Volume 1, Stuttgart 1950, Col. 844-854, here: 850f.

- ↑ Augustine, De civitate dei 14.9.

- ^ Pierre Miquel: Lexique du désert , Bégrolles-en-Mauges 1986, p. 129.

- ↑ Michel Foucault: Sécurité, territoire, population , Paris 2004, p. 181 f.

- ^ Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou. Frankfurt am Main 1987, p. 117 ff .; Paul Wilpert offers numerous examples: Ataraxia . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity. Volume 1, Stuttgart 1950, Col. 844-854, here: 851.

- ↑ Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou , Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 110-115.

- ↑ Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou , Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 127-141.

- ↑ Herbert Frohnhofen: Apatheia tou theou , Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 158-172.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: The Metaphysics of Morals , Part 2, Introduction XVI.

- ↑ Ina Goy, Otfried Höffe : Apathy, moral . In: Marcus Willaschek et al. (Ed.): Kant-Lexikon , Vol. 1, Berlin / Boston 2015, p. 144.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: Anthropology in a pragmatic way, § 75.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant: Critique of Judgment § 29.