Philebos

The Philebos ( ancient Greek Φίληβος Phílēbos , Latinized Philebus ) is a work of the Greek philosopher Plato written in dialogue form . A fictional conversation between Plato's teacher Socrates and the two young Athenians Philebos and Protarchus is reproduced . The main topic is the ethical evaluation of pleasure .

Philebos and Protarchos are hedonists , they regard pleasure as the highest value and equate it with the absolutely good . Socrates takes the opposite position, for him reason and insight have priority. He does not deny the justification and value of pleasure, but he shows the diversity of pleasures and advocates a differentiated assessment. He rejects some kinds of pleasure because they are harmful, and grants the rest, the “pure” pleasures, only a subordinate rank in the hierarchical order of values. The distinction between the types of pleasure leads to general considerations about the unity and multiplicity of types, which are summarized under a generic term, and about the genera into which all that beings can be divided.

Pleasure and displeasure occur in different manifestations and proportions in human life. Socrates examines the causes, the genesis and the nature of these factors and their changing combinations, which give rise to different states of mind. The particularities of the individual forms of pleasure are worked out and the reasons for their different evaluations are explained. At the end of the dialogue, Socrates presents a universal order of values. The right measure, proportionality, takes the top place and pleasure - as far as it is justified - the bottom. Harmful lusts are to be avoided. The right mixture of the desired factors should enable a successful life and bring about a balanced state of mind. Protarchus sees this, Philebus no longer expresses himself.

The Philebos , in which a number of other philosophical questions come up in addition to the core topic, is considered to be one of the most demanding dialogues of Plato. In modern research, the division of all beings into four classes by Socrates receives a lot of attention. Among other things, the relationship of this classification to Plato's theory of ideas and to his “ unwritten teaching ” or principles is discussed .

Place, time and participants

In contrast to some other Platonic dialogues, the Philebos is not designed as a narrative narrative. The dialogue is not embedded in a framework, but starts suddenly. You don't learn anything about the place, time or occasion of the conversation. In any case, the only possible setting is Athens, the hometown of Socrates. In addition to the three interlocutors Socrates, Protarchus and Philebos, there is also a crowd of young men present, who only listen in silence. They are apparently admirers of Philebos, whose beauty is valued in the homoerotic milieu. Philebos only plays a minor role, although the dialogue is named after him. The debate takes place between Socrates and Protarchus.

As in most Platonic dialogues, Socrates is the main character, the knowledgeable philosopher who directs and dominates the debate and helps others to gain knowledge. In contrast to the early dialogues, where he holds back with his own view and brings new ideas to his interlocutors with goal-oriented questions, here he develops his own theory. Since the dialogue is a literary fiction, the concept that Plato puts Socrates in the mouth should not be taken as the position of the historical Socrates, although the ethical attitude of the dialogue figure should roughly correspond to the basic attitude of their real model.

Philebos is young, more of a youth than a young man. There is no evidence outside of the dialogue for the existence of a historical acquaintance of Socrates by the name of Philebus. It is quite possible that it is a fictitious figure. This is supported by the fact that no historical bearer of this name is known and that it is a descriptive name that fits the figure ("youth lover" or "friend of youthful lust"). Further indications of fictionality are that the name of his father is not mentioned and Plato did not give him a profile that could enable a historical classification. It is noticeable that Philebos is the title figure and sets up the initial thesis, but leaves the defense of the thesis to Protarchus, while he himself rests and listens. He only rarely and briefly takes the floor, and in the end he accepts the refutation of his thesis without comment. He is lazy and interested only in pleasure and shies away from the mental effort of a debate. His worldview is simple. With his appearance and his whole demeanor he corresponds to the negative image of an inept, self-satisfied and unteachable hedonist that the author wants to present to the reader. It is possible that Plato gave him features of the mathematician and philosopher Eudoxus of Knidos . Eudoxus, a younger contemporary of Plato, was a hedonist, and according to a research hypothesis, the criticism of hedonism in Philebos was directed against his teaching. However, Plato's Philebos shows less intelligence and less interest in exchanging ideas than one would expect from a capable scientist like Eudoxus. Its beauty is repeatedly emphasized. His special relationship with the goddess of love Aphrodite , whom he gives the name of lust (Hedone), fits his erotic attractiveness ; apparently he is of the opinion that his commitment to hedonism is acting in the interests of the goddess. The fact that Philebos does not take part in the philosophical investigation suggests that he embodies an irrational principle which as such does not account.

In the case of Protarchus, the probability that it is a historical person is rated higher than that of Philebos, but there are doubts in this case too. In the dialogue Socrates calls him "son of Callias". Whether the rich Athenian is meant, who in the research literature " Callias III. “Is called is controversial. Dorothea Frede believes that Protarchus was one of the two sons of Callias III. mentioned in Plato's Apology . According to Plato's information, they were informed by the sophist Euenos of Paros. In the Philebos Protarchus speaks respectfully of the famous rhetoric teacher Gorgias and reveals himself to be his eager student. It is possible that Plato's Protarchus can be identified with an author - apparently a rhetorician - of this name, whom Aristotle quotes.

As a dialogue figure, Protarchos, like Philebos, is a representative of the Athenian upper class, in whom educational efforts were valued at the time of Socrates and philosophical topics also met with interest. In contrast to Philebos, Protarchus proves to be willing to learn and flexible. He appears modest and is ready to subject his hedonistic worldview to an impartial test, while Philebos announces at the beginning that he will not change his mind under any circumstances. Finally, Protarchus lets himself be convinced by Socrates after trying for a long time to defend his position.

content

Working out the prerequisites

The starting point

The presentation starts suddenly in an ongoing conversation. Philebos put forward the thesis that what is good and worth striving for is pleasure or pleasure (hēdonḗ) for all living beings . Pleasure brings about the state of eudaimonia ("bliss") and thus brings about a successful life. Socrates has denied this and pleaded for the counter-thesis that there are more important and more advantageous things: reason, knowledge and memory, a correct understanding and truthful reflection. When trying to come to terms with it, Philebos is tired. Exhausted, he now leaves Protarchus the task of defending the common position of the two against the criticism of Socrates. Protarchus wants to discuss openly, while Philebos declares frankly that he will always hold on to the priority of pleasure.

Lust and lust

Socrates begins his criticism of the glorification of pleasure by pointing out that pleasure is not at all a simple, uniform fact. Rather, there are diverse and even dissimilar phenomena that are summarized under this term. The pleasure of a dissolute person cannot be compared with that of a level-headed person and that of a sensible person cannot be compared with that of a confused person. Protarchus counters this by saying that the causes of the pleasant feelings are indeed opposing facts, but the effect is always the same. He thinks that pleasure is always just pleasure and always good. Socrates makes a comparison with the term “color”: Both black and white are colors, and yet one is the exact opposite of the other. Analogously there are opposing desires; some are bad, others are good. Protarchus does not initially admit this. Only when Socrates also called his favorite good, knowledge, as inconsistent, does Protarchus admit the variety of desires, since his position is now not disadvantaged by this view.

Unity and multiplicity

The general problem that the interlocutors encountered is the relationship between unity and multiplicity, one of the core themes of Platonic philosophy. The question arises as to how it is possible that the lusts or the knowledge are on the one hand different, but on the other hand still form a unit that justifies the common term. It is not about the individual concrete phenomena, the obvious diversity of which is trivial, but about the general that underlies them, that is to say about concepts such as “man”, “beautiful” or “good” and their subdivisions.

In the Platonic doctrine of ideas , to which Socrates alludes, such terms are understood as “Platonic ideas”, that is, as independently existing, unchangeable metaphysical givens. The ideas are causative powers, they evoke the phenomena corresponding to them in the visible world. Here, however, a fundamental problem of this Platonic model becomes apparent: on the one hand, the individual ideas are considered separate, uniform, unchangeable entities , i.e. are strictly separated from each other and from the perceptible phenomena, on the other hand they are still closely related to the realm of sense objects are somehow present there, because they cause the existence and the nature of everything that arises and passes there. The Platonic idea is a stable, limited unity and at the same time appears as a limitless multiplicity, thus unifying opposites. That seems paradoxical and should now be made understandable.

The insight that things consist of one and many and that in them limitation and infinity meet, Socrates calls a gift from the gods. He is reminiscent of the mythical Prometheus , to whom, according to legend, people owe fire. The task of the philosopher is to examine and describe the structure of the total reality formed by unity and multiplicity. It all depends on accuracy. It is not enough to establish the transition from a delimited unity to an unlimited multiplicity as a matter of fact. Rather, the number of intermediate levels, the middle area between the absolutely uniform one and the world of limitlessness, is to be determined. If the intermediate area is properly explored, then reality is properly explored in a philosophical manner. Otherwise, you will get lost in the fruitless quibbles that become an end in themselves for contentious debaters.

The exploration of the tiered reality

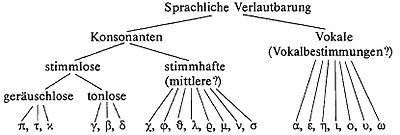

Socrates illustrates what is meant by means of examples. “Speech sound” and “sound” are general terms that encompass an unlimited variety of individual acoustic phenomena. Language consists of sounds, music consists of tones. Anyone who only knows the general terms “sound” and “tone” and the existence of an abundance of corresponding individual phenomena does not yet have any useful knowledge. Linguistically or musically competent is only someone who knows the number and types of relevant sounds or tones, i.e. who can completely and correctly classify the individual elements of the respective set. For this purpose one starts from the most general generic term, the genus “linguistic pronouncement” or “tone”. One determines which sub-genera this genus consists of and how these in turn break down into species and sub-species. In this way one progresses from the general to the particular and grasps the structure of the relevant field of knowledge. In the field of linguistic sounds, for example, it turns out that they break down into consonants and vowels. A distinction is made between unvoiced and voiced consonants , and the unvoiced again have two subspecies. On the lowest level you get to the individual sounds, which cannot be further subdivided. You can find out how many of them there are and what classes they belong to. The general terms “pleasure” and “insight” (or “reason”) should be used analogously if one wants to become knowledgeable. This system of methodically carried out term classification is known today as Dihairesis (diheresis).

The classification of pleasure and reason in a classification system

First, however, Socrates brings up another consideration, with which he returns to the initial question of the hierarchy of goods. He suggests examining the possibility that neither pleasure nor reason is the highest good, but a third good that is superior to both. The highest good can only be “ the good ”, the absolutely good, which nothing is surpassed and which lacks nothing for perfection. But this can neither apply to pleasure nor to reason. A comfortable life without a mind function would be similar to that of a lower animal unaware of the past or the future and not even able to appreciate its present well-being, and a sane life without sentience does not seem desirable. Both factors are therefore needed, and neither can be equated with the absolutely good. It remains to be clarified which of them is more valuable. Protarchus fears that lust will do badly, but does not want to give up trying to find the truth.

Before the new investigation can begin, the general question of the classification of the totality of beings must be clarified. The whole of reality can be divided into four genres: the unlimited (ápeiron) or the limitless, the limitation (péras) or the borderline, the mixture of these two and the cause of the mixture. Everything that can be increased and decreased at will, such as “warm” and “cold”, “large” and “small”, “fast” and “slow” belongs to the category of the unlimited, while equality and all mathematically expressible conditions belong to the borderline as certain quantities. The mixture of these two genres is due to the fact that certain limits are set for what is by its nature unlimited and so structures that depend on numbers arise. For example, music is created through a certain mixture of high and low, fast and slow, based on numerical relationships. Health, too, is a mixture of factors that, taken alone, would cause excess and disease. Such mixtures are not arbitrary and arbitrary, but are ordered and measured. Their cause - the fourth genus - is what tames what tends to be unlimited through measure and order, ensures the right proportions and thus creates everything beautiful and valuable.

Pleasure and displeasure are now classified in this classification. "Pleasure" means all pleasant feelings, "Pain" means all unpleasant ones. Both are part of the arbitrary increase and thus unlimited. The human life mixed from them is to be assigned to the third species, the things that have arisen through the limitation of the unlimited. The task of reason is to ensure the correct mixing ratio. Thus it belongs to the fourth genus, to the causes of the mixture, which give structure to the disordered and excessive. This applies not only to reason in man, but also analogously to reason that rules and orders the entire cosmos. The world reason, for example, ensures the regular movements of the heavenly bodies and the change of seasons. Only that which is animated can be rational; Just as reason presupposes a soul in man, the sensible and beautifully ordered cosmos must also have a soul, the world soul .

The closer examination of pleasure and displeasure

Two main types of pleasure and discomfort

In the next step, Socrates returns to the question of the types of pleasure and discomfort. He assumes the origin of both states of the human mind. He sees their cause in the genus. By this he does not mean the species to which pleasure and displeasure belong, but that of the mind, for the mind is the location of both states, insofar as they occur concretely in man. The mind belongs to the genus of things that have arisen through the limitation of the unlimited, that is, that is characterized by mixture. In living beings, nature has created a harmonious order through the sensible mixing and limitation of factors that tend to be unlimited. This is shown, among other things, in health. Such a harmonious state is not characterized by pleasure or displeasure. Both only appear when the harmony is disturbed and dissolves. Any such disturbance is felt as pain; their removal is accompanied by a feeling of pleasure as a return to natural harmony. For example, hunger and thirst are forms of displeasure that result from deficiencies - disturbances of a natural balance; their elimination by eliminating the deficiency is associated with pleasure. An unnatural excess of heat or cold also causes displeasure, while the return to harmony through cooling or warming causes a pleasant feeling.

The phenomena mentioned are a first type of pleasure and displeasure caused by current physical conditions. A second kind arises in the soul through the mere expectation of something pleasurable and painful; its cause is the memory of corresponding experiences. It should also be noted that there is also a third state besides the pleasurable and the painful. That is the harmonious and undisturbed one, in which pleasure and displeasure do not occur in excess. Avoiding sharp fluctuations between pleasure and pain is characteristic of a rational way of life.

Socrates then turns to the kind of pleasure and discomfort that is not a response to current physical processes. It is triggered by ideas that arise from memory. This is about a pleasure that is generated by the soul alone without the body. The soul searches for pleasure in the world of its memories and ideas. Such striving manifests itself as a desire for something. Desire is always a striving for the opposite of the present state; Emptiness evokes the need for abundance. You have to already know the opposite in order to strive for it. Only the soul is able to do this, because only it has memories. The body is limited to the present and therefore cannot desire anything. Thus all desires are of a purely spiritual nature.

Truth and imagination in pleasure and displeasure

Next, the mixture of pleasure and displeasure is examined more closely. The question arises what these sensations have to do with reality and illusion.

The meeting of sensations triggered by the body with purely mentally conditioned feelings creates different mixtures of pleasure and pain. When a person suffers from a physical deficiency - an "emptiness" - his pain is either alleviated or intensified by his simultaneous presentations, depending on whether he is expecting the regaining of the longed for abundance or the memory of abundance is connected with hopelessness. Ideas and expectations that create feelings can be realistic or erroneous. Thus, they each have a certain relationship to truth and untruth. Likewise, according to Socrates' thesis, the sensations of pleasure and discomfort they evoke are related to truth and falsehood. This means that there is “true” and “false” lust. A pleasure experienced in a dream or in madness is of a different quality than one that has a relation to reality. One must distinguish between well-founded and illusory pleasure and displeasure; lust on an illusory basis is wrong, it lacks the truth. Protarchus sees it differently. For him, pleasure always has the same quality, whether its cause is real or just imagined. An opinion can be wrong, but pleasure is always "true" through its very existence.

However, Protarchus admits that both opinions and lusts can have the quality of badness. This is the starting point for the counter-argument of Socrates, who asserts analogies for falsehood: Like an opinion, a joy or a pain can also be wrong. When it comes to opinions, the qualities “wrong” and “right” depend on the truth content. Socrates wants to apply this definition to the associated sensations: It is possible to feel pleasure or pain about something only because one is wrong about it. Then one not only has a wrong opinion about it, but also the pleasure or pain is based on a wrong assumption, is wrong and therefore "wrong". Protarchus rejects this. He maintains that only opinion is wrong. He thinks the desire to call it “wrong” is absurd.

Opinions arise, as Socrates now explains, from the comparison of perceptions with memories of earlier perceptions. But this comparison can go wrong; Perceptions and memories of them can be erroneous. Socrates compares the soul in which the memories are recorded to a book that contains true and false accounts that a scribe recorded there and illustrated by a painter. The recordings in memory, including the images, trigger hopes and fears, pleasant and unpleasant feelings in the soul that is looking at them. However, since some records are wrong and much of what is hoped for or feared will not occur, the pleasure and discomfort generated by such memories and expectations is also illusory. Just like an incorrect opinion, it has no correlate in reality and is therefore wrong. Bad people have false records, they live in illusions, and their joys are "false" because they are just ridiculous imitations of true joys. The wickedness of bad lusts rests on their falsehood. Protarchus agrees with some of these considerations, but contradicts the last thesis: It does not make sense to him that badness should necessarily be traced back to falsehood. In his view, pleasure and displeasure can be bad insofar as they are connected with bad, but this badness is not a consequence of their falsehood, as is the case with opinions, it does not consist in a specific relationship to truth and untruth.

Socrates then makes a new argument. He points out that the judgment on the strength of lust and pain depends on the point of view you take towards them when you assess them comparatively. He compares this dependence on perspective with optical illusions in order to show that there can be wrong things with lust as well as with sensory impressions.

Lustful, sorrowful and measured life

Now Socrates takes a new approach. The starting point is the observation that only relatively strong physical changes are perceived and arouse pleasure and displeasure. Therefore, there is not only a life marked by pleasure and a life marked by suffering, but also a third, neutral way of life, in which pleasure and pain hardly appear, since the fluctuations in the state of the body are weak. With this statement, Socrates turns against the teaching of certain influential philosophers who only differentiate between pleasure and displeasure and claim that pleasure consists in nothing other than painlessness or freedom from discomfort, i.e. in the neutral state. In defining pleasure as the mere absence of displeasure, these thinkers do not ascribe to it any independent reality. This turns out to be the sharpest opponents of hedonism.

One argument of the anti-pleasure philosophers could be: The strongest forms of pleasure and displeasure generate the greatest desires. Sick people experience more severe deficiencies than healthy people. Therefore, they have more intense desires and feel more lust when they are satisfied. Their pleasure does not exceed the amount, but the intensity of the healthy ones. It is the same with the dissolute who tend to excess: their lust is more intense than that of the prudent and moderate who do not exaggerate anything. That means: A bad state of body and soul enables the greatest pleasure. So pleasure does not originate in excellence ( aretḗ ) , but in its opposite.

In order to test the argument, Socrates first considers the three types of pleasure: those that are only physically conditioned, those that are purely emotional, and those that are brought about by both factors. It turns out that with all three types the most intense lusts are by no means particularly pure - that is, free from unpleasant aspects. Rather, they are all characterized by a considerable admixture of discomfort. This can be seen well in the theater with purely emotional lusts, for example in a tragedy where the audience sheds tears and rejoices at the same time. The mixture is also evident in comedy: the audience laughs, so they feel pleasure, but pleasure is based on resentment, a negative emotion that represents a form of displeasure. It is joy over an evil. One is happy that the theater characters are ridiculous and fall prey to their ignorance and incompetence. This is how pleasure and displeasure mix. This happens not only when looking at what's going on in the theater, but also in the tragedy and comedy of life. As with resentment, it is also with feelings like anger, longing, sadness, fear and jealousy. All of them are not pure, but mixed with pleasure and displeasure.

Socrates has shown that many pleasures desired by humans - especially the most intense ones - cannot be explained as states of pure pleasure, but are each based on a certain mixture of pleasure and discomfort. From this point of view, too, the term "false pleasure" proves to be justified. Accordingly, only pure lusts are true or genuine, that is, lusts that neither arise from the elimination of a displeasure nor even have an admixture of displeasure. As Socrates explains, pure lusts by no means consist in the absence of displeasure, but have their own reality and quality. For example, they relate to beautiful colors and shapes as well as pleasant smells and tones. This also includes the joy of learning, of gaining knowledge. Such joys, in contrast to violent lusts, are moderate. Socrates emphasizes that the purity of pleasure is all that matters, not its quantity or intensity; the slightest pure pleasure is more pleasant, more beautiful, and truer than the greatest impure.

The transience of lust

Socrates now touches on another topic: the relationship between pleasure and being and becoming. With this he refers to the philosophical distinction between the eternal, perfect and self-sufficient being on the one hand and the transitory, imperfect and dependent becoming on the other. The being is cause, the becoming is caused. All pleasure arises and passes. Since it belongs to the realm of the caused and the transitory, there is no true being to it, but only a becoming. This shows their inferiority, because everything that is becoming and that is exposed to decay is inherently defective and always needs something else. Here Socrates returns to the initial question of the dialogue. His argument is: Everything that is becoming is aligned with a being that is superior to it. Becoming is not an end in itself, but every process of becoming takes place for the sake of being. The good as the highest value can therefore not be something that arises for the sake of another, but only that for whose sake something becomes arises. Socrates means that he has shown that equating pleasure with good is ridiculous. He adds further arguments. Protarchus sees the conclusiveness of the argument.

The investigation of reason

After examining the value of pleasure, Socrates subjects reason and knowledge to an analogous test. Again, it is about the question of “purity” and “truth”, here based on the accuracy and reliability of the results that the individual fields of knowledge - handicrafts and sciences - deliver. If one looks at the usefulness of the fields of knowledge from this point of view, then the superiority of the subjects in which calculations and measurements are carried out over the less precise ones in which one has to rely on observation and estimation. At the same time, it can be seen that pure theory, which deals with absolute givens , is fundamentally superior to empiricism , which only deals with approximations. In this sense, pure geometry takes precedence over architecture as applied geometry.

The quality of the approach is of decisive importance for the science systematics. In this respect dialectics , the expert, systematic analysis according to the rules of logic, is superior to all other sciences. It deserves priority because it gives the clearest and most accurate results with the highest degree of truth. Their object is the realm of unchangeable being to which absolute purity and truth belong. The more impermanent something is, the further it is from the truth. There can be no reliable knowledge about things that are changeable.

The hierarchy of goods

The hierarchy of goods results from the considerations so far. Reason is closer to the true, the real, the absolutely good than pleasure, and therefore it ranks above it. However, reason is not identical with good, because otherwise it alone would suffice for humans and pleasure would be superfluous.

In determining what is good in terms of human life, Socrates falls back on the knowledge already gained that life is mixed of pleasure and displeasure and therefore the right mixture is important. Human life is a mixture of different factors. The question now arises as to what kinds of knowledge should be included in the mix. It turns out that not only the highest and most reliable knowledge, pure theory, is required for a successful life, but also some empirical and technical knowledge is required despite its inaccuracy. Since no subordinate knowledge can ever harm when the superior is there, all types of knowledge are welcome. The situation is different with pleasure. The greatest and most violent desires are very harmful because they destroy knowledge. Therefore, only the “true” lusts that are pure and in harmony with prudence may be allowed.

Now we have to investigate what constitutes the good, valuable mixture that makes a successful life possible. The question arises as to whether this decisive factor is more related to pleasure or reason. Socrates thinks the answer is simple, even trivial, because everyone knows it: the quality of a mixture always depends on the correct measure and proportionality. In the absence of these, there is always ruinous chaos. The right measure is revealed in the form of beauty and excellence. In addition, truth must definitely be mixed in. In human life, the good does not appear immediately in its unity, but it can be grasped as beauty, appropriateness and truth. The effectiveness of the good "found refuge in the nature of the beautiful".

From these considerations, the precise determination of the hierarchical ranking of goods finally results. Reason is far superior to pleasure, since it has a greater share in truth as well as measure and beauty. The highest of goods below the absolutely good is the right measure, followed by beauty and third by reason. Fourth place is occupied by the sciences, the arts and true opinions, the fifth by pure lust. This finding does not change even if all oxen, horses and other animals stand together for the primacy of pleasure by chasing after it. Protarchus agrees to this also in the name of Philebus. Philebos no longer speaks.

Philosophical content

The starting point of the discussion is the old controversial question , already addressed by Hesiod , whether pleasure or reason, knowledge and virtue deserve priority. However, Plato does not limit himself to clarifying this question, but takes the topic as an opportunity to outline a philosophical theory of the entire reality of beings and things becoming.

A main thought elaborated in Philebos is the extraordinary importance of measure. For Plato's Socrates, proportion and proportionality play a central role both in the world order and in human life as the basis of everything good and beautiful. It is contrasted with the immensity of hedonistic debauchery. The emphasis on the mathematical world order and its philosophical exploration as well as the pair of opposites limitation and limitlessness shows the influence of Pythagorean ideas.

The connection between the four classes of beings introduced by Plato's Socrates and the Platonic doctrine of ideas presents difficulties. The question of whether the classes - or at least some of them - are to be understood as ideas is controversial. In particular, the assumption that the unlimited is also an idea is problematic and discussed controversially. It was also discussed whether the ideas should be classified in one of the four genres or identified with one of them.

It is also unclear what role the doctrine of ideas plays in Philebos . Since it is not expressly addressed, it has been assumed that it is not present here. This assumption fits with the hypothesis that Plato distanced himself from the theory of ideas in his last creative period, that he gave it up or at least considered it to be in need of revision. However, his Socrates in Philebos places great emphasis on the distinction between the higher domain of unchangeable being and the world of arising and passing away that depends on it. Thus, Plato stuck to at least one core element of the concept on which the theory of ideas is based. The question of whether he has changed his basic position is highly controversial in research. The view of the “Unitarians”, who believe that he had consistently represented a coherent point of view, runs counter to the “development hypothesis” of the “revisionists”, who assume a departure from the theory of ideas or at least from its “classic” variant. From a Unitarian point of view, the worldview presented in Philebos is interpreted as an answer to the problematization of the doctrine of ideas in the Parmenides dialogue .

Formulations such as “becoming to being” (génesis eis ousían) point to Plato's examination of the question of how the connection between the two essentially different areas of being and becoming is to be explained. This problem, which is known in modern research by the technical term chorismos , has preoccupied him.

The difficult interpretation and the conclusiveness of Socrates' argumentation to justify the "falseness" of lusts is discussed particularly intensely. It is about the questions of what exactly the term "wrong" means in this context and to which aspect of certain lusts it refers. It is discussed whether, for Plato's Socrates, false pleasure, because of its illusory character, is not real pleasure, but only appears to be one of the pleasures, or whether it is a falsehood analogous to the error of an opinion. In the latter case, falsehood is a defect that does not prevent pleasure from actually being present.

Another subject of controversial debates is the relationship between the metaphysics of Philebos and Plato's “ unwritten doctrine ” or “ doctrine of principles”, which he never put down in writing for fundamental reasons. According to a highly controversial research opinion, the basic features of this teaching can be reconstructed from individual hints in the dialogues and information in other sources ("Tübingen and Milan Plato School", "Tübingen Paradigm"). Proponents of this hypothesis believe that they have discovered references to the doctrine of principles in Philebos or that they can explain utterances in dialogue in the light of the doctrine of principles. According to an interpretation based on this understanding , the terms “limitation” and “the unlimited” used in Philebos correspond to the terms “the one” ( to hen , unity) and “unlimited” or “indefinite” duality (ahóristos dyás) of the doctrine of principles. The “more and less” in Philebos , the ability to increase and decrease, is accordingly “the big and small” or “the big and small” (to méga kai to mikrón) of the doctrine of principles; Plato is said to have used this concept to describe the indefinite duality.

It is also discussed whether Plato presents an overall interpretation of pleasure that encompasses all types of pleasure, or whether the types are so fundamentally different for him that he renounces a general definition of the nature of pleasure. The former interpretation is the traditional and prevalent.

Mark Moes puts a therapeutic goal of dialogue in the foreground. According to his interpretation, it is primarily a matter of Socrates appearing as a therapist, as a "soul doctor" who, analogous to the procedure of a doctor, first makes a diagnosis and then turns to therapy. Accordingly, it is about the health of the soul, which Socrates sees damaged by hedonism. His efforts are aimed at healing Protarchus by leading him to the right way of life. This effect should also be achieved with hedonistically minded readers.

Emergence

In research there is almost unanimous agreement that the Philebos is one of Plato's late dialogues. This is supported by both the statistical findings and the similarity in content to other later works, especially the Timaeus . However, the decisive role of the figure of Socrates for the later work is untypical. Occasionally a somewhat earlier date - originating in the last phase of Plato's middle creative period - is preferred. There is a lack of sufficient clues for a more precise classification within the group of late dialogues. The hypothesis that Philebos was Plato's reaction to the hedonism of Eudoxus of Knidos has led to the assumption that the writing was soon after 360 BC. Is to be dated, but this is very uncertain.

Text transmission

The ancient text tradition is limited to a few small papyrus fragments. The oldest surviving medieval Philebos manuscript was made in 895 in the Byzantine Empire for Arethas of Caesarea . The text transmission of the Philebos is because of some corruptions more problematic than that of other dialogues, so it presents the textual criticism with special challenges.

reception

Ancient and Middle Ages

Plato's student Aristotle dealt intensively with the Platonic doctrine of pleasure. He did not mention the Philebos by name anywhere, but he often referred to him in terms of content. In addition, he may have had it in mind in his statements about the unwritten teaching. Aristotle's student Theophrastus contradicted the thesis of Plato's Socrates that there is a false pleasure and admitted to the view of Protarchos that all pleasures are “true”.

In the tetralogical order of the works of Plato, which apparently in the 1st century BC Was introduced, the Philebos belongs to the third tetralogy. The historian of philosophy, Diogenes Laertios , counted it among the “ethical” writings and gave “About lust” as an alternative title. In doing so, he referred to a now-lost work by the scholar Thrasyllos .

The rhetoric and literary critic Dionysius of Halicarnassus valued Philebus ; he praised the fact that Plato had retained the Socratic style in this work. The famous doctor Galen wrote a now lost work “On the Transitions in Philebos”, in which he examined the process of inference in dialogue.

In the period of Middle Platonism (1st century BC to 3rd century), the Philebos apparently received little attention from the Platonists. Plutarch tried to connect the four classes of beings, which Plato's Socrates distinguishes in Philebos , with the five "greatest genera" named in the Sophist dialogue by adding a fifth class and interpreting the classes as images of the genera. In the 3rd century a Middle Platonist named Eubulus who lived in Athens wrote a now-lost script in which he dealt with Philebus , among other things . The Middle Platonist Democritus , who also lived in the 3rd century, also dealt with dialogue; whether he wrote a comment is unclear.

The Neoplatonists showed a greater interest in the Philebos . They were particularly interested in the metaphysical aspects of the dialogue, but also received ethical consideration. Plotinus († 270), the founder of Neoplatonism, often referred to Philebos in his treatise on How the Multiplicity of Ideas came about and on the good . Plotin's most famous student Porphyrios († 301/305) wrote a Philebos commentary, of which only fragments have survived. His classmate Amelios Gentilianos may also have written a comment. Porphyrios' pupil Iamblichos († around 320/325), a leading exponent of late ancient Neo-Platonism, had Philebus studied in his school as one of the twelve most important dialogues of Plato from his point of view. He wrote a commentary on it, of which only a few fragments have survived. The Neoplatonists Proklos and Marinos von Neapolis , who taught in Athens in the 5th century, also commented on the dialogue. Marinos, a student of Proclus, burned his long commentary after the philosopher Isidore , whom he had asked for a comment, criticized the work and expressed the opinion that Proclus' comment was sufficient. Perhaps Theodoros von Asine and Syrianos also wrote comments. Not a single work of this literature has survived. Only the postscript of a course by Damascius († after 538) on Philebos has survived. It was earlier wrongly ascribed to Olympiodorus the Younger . Damascius took a critical position on Proclus' interpretation of Philebus .

In the Middle Ages the dialogue was known to some Byzantine scholars, but the Latin-speaking educated Westerners had no access to the work.

Early modern age

In the West, the Philebos was rediscovered in the age of Renaissance humanism . The famous humanist and Plato expert Marsilio Ficino , who worked in Florence, held him in high regard . He made a Latin translation. When his patron, the statesman Cosimo de 'Medici , was lying on his death bed in July 1464, Ficino read him the Latin text. Already at the beginning of 1464 Cosimo had expressed his special interest in Philebos , “Plato's book on the highest good”, since he was striving for nothing more than knowledge of the surest path to happiness. Ficino published the Latin Philebos in Florence in 1484 in the complete edition of his Plato translations. He also wrote a commentary on the dialogue, the third, final version of which was printed in 1496, and gave lectures to a large audience on the issues discussed in the Philebos . His aim was to promote Platonism and to push back the influence of contemporary Aristotelians .

The first edition of the Greek text appeared in Venice in September 1513 by Aldo Manuzio as part of the first complete edition of Plato's works. The editor was Markos Musuros .

In his Dialog Utopia , published in 1516, Thomas More presented a concept of pleasure that reveals his engagement with the ideas of Philebos .

Modern

Philosophical Aspects

The Philebos is considered demanding and difficult to understand. As early as 1809, the influential Plato translator Friedrich Schleiermacher remarked in the introduction to the first edition of his translation of the dialogue: “This conversation has always been regarded as one of the most important, but also the most difficult, of Plato's works.” In recent research it is emphasized, however, that the structure of Philebos has been well thought out. Among other things, the doctrine of affect and the approach to a theory of the comic, which is the first traditional attempt of this kind, are recognized.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel found “the esoteric element of Platonic philosophy” in Philebos ; this is to be understood as speculative, which is published, but remains hidden “for those who are not interested in grasping it”. Apparently pleasure belongs in the circle of the concrete, but one has to know that the pure thoughts are the substantial, whereby everything is decided about everything, however concrete. The nature of pleasure results from the nature of the infinite, indefinite, to which it belongs.

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling appreciated the Philebos . In his essay Timaeus , written in 1794 , a youth work, he dealt with the question of the creation of a perceptible world. In doing so he drew on the Philebos . He was particularly interested in the four genres, which he called “general world concepts”, and “becoming to being”. He emphasized that the four genera should not be understood as concepts of entities , they are not designations for something that is, but categories for everything that is real. The unlimited is to be interpreted as the principle of the reality of everything real, also as the principle of quality, the limitation as the principle of quantity and the form of everything real. In his Dialogue Bruno (1802), Schelling referred to the Philebos when determining the subject of philosophy .

In 1903 the Neo-Kantian Paul Natorp presented his treatise Plato's theory of ideas , in which he also went into detail on the Philebos , which he described as a deeply penetrating psychological investigation. It is one of the most important dialogues for Platonic logic. Unfortunately, Plato did not take the step towards a science of becoming, a “logical foundation of empirical science”, despite decisive steps in this direction, but held on to a sharp contrast between the changeable and the unchangeable.

Hans-Georg Gadamer examined the Philebos in detail from a phenomenological point of view in his Marburg habilitation thesis published in 1931 . Later he also dealt intensively with the dialogue, which he interpreted hermeneutically . Using Philebos, he tried to show that the idea of the good, according to Plato, was immanent in human life and an aspect of lived experience. With this he moved Plato's way of thinking close to that of Aristotle; he thought that Aristotelian ideas were anticipated in the Philebos . With this approach of the habilitation thesis he was under the influence of his teacher Martin Heidegger , from whose point of view he later distanced himself in part. In the context of an understanding based on Heidegger, Gadamer found Plato's idea of a “true” or “false” pleasure comprehensible. Pleasure, perceived in this way, is "true, provided that what is in it is supposed to be enjoyable, which is enjoyable". The state of pleasure is always "understood from the fact that it has discovered that which is 'where' one has it". Plato sees it “as a way of discovering the world in encounter”. This concept of pleasure corresponded to Gadamer's own view; he assumed with Heidegger that affects are a unique way of discovering beings, regardless of their connection with opinions. In addition, Gadamer represented the equation of the good with the beautiful, with which he "aestheticized" the Platonic ethics. Dealing with the Philebos , especially with the understanding of dialectics presented there, played an essential role in the development of Gadamer's philosophy.

The philosopher Herbert Marcuse dealt with the Philebos in his 1938 publication On the Critique of Hedonism . He found that Plato was the first thinker to develop the concept of true and false need, true and false pleasure, and thus introduced truth and falsehood as categories that could be applied to every single pleasure. In this way happiness is subjected to the criterion of truth. Pleasure must be accessible to the distinction between truth and falsehood, right and wrong, otherwise happiness is inextricably linked with unhappiness. The reason for the distinction cannot, however, lie in the individual sensation of pleasure as such. Rather, pleasure becomes untrue if the object it refers to is "in itself" not at all pleasurable. The question of truth concerns not only the object, but also the subject of pleasure. Plato combines the goodness of man with the truth of pleasure and thus turns pleasure into a moral problem. In this way, pleasure is placed under the demands of society and enters the realm of duty. By assigning exclusively inanimate objects as objects to “pure” pleasure, which he is the only one to approve of, that is, the things furthest away from the social process of life, he separates it “from all essential personal relationships”.

The American philosopher Donald Davidson , an influential exponent of analytical philosophy , received his doctorate in 1949 from Harvard University with a dissertation on the philebos . He took a “revisionist” position: when Plato wrote this dialogue, he no longer believed that the theory of ideas could be the main basis of a concept of ethics. He has given up the idea of a close connection between ideas and values. Therefore, he had to find a new approach to his ethics.

Jacques Derrida dealt in his essai La double séance ("The double séance"), which is part of his work La dissémination , published in 1972 , with written form and mimesis . As a starting point he chose the passage in Philebos where the soul is compared to a book containing the notes of a scribe and pictures of a painter.

William KC Guthrie criticized a lack of clarity in the terminology of Philebos , particularly with regard to the term "pleasure", and said that Socrates' reasoning was not convincing; his statements are more of a creed than a philosophical inquiry. In contrast to Philebos, Protarchus is not a real hedonist, because such a hedonist would have defended his position more decisively.

The philosopher Karl-Heinz Volkmann-Schluck counted the essential analysis of pleasure offered in Philebos “to the greatest thing that Plato thought”. It was continued by Aristotle, but then disappeared as a central theme of philosophical thought. Only Friedrich Nietzsche took up the subject again.

Literary aspects

Friedrich Schleiermacher, who valued the content of the Philebos , made derogatory comments about the literary quality. He found that from this point of view the dialogue did not grant the pure enjoyment one is used to from other works of Plato; the dialogical character does not really emerge, the dialogical is only an external form. The renowned philologist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff , who also disapproved of the literary design , expressed himself in this sense ; it is a school disputation without artistic appeal and only the shadow of a Socratic dialogue. The form of conversation has frozen, the dramatic power has died. But Plato had important things to say about the matter. Nietzsche considered the "question and answer game" to be a "transparent cover for the communication of finished constructions". Paul Friedländer was of a different opinion ; he said that the artistic quality is mostly misunderstood by modern readers. The lack of understanding of the “dialogical liveliness” is evident from the incorrect punctuation in the text output. Olof Gigon judged that the scenery only appears lively at first glance, that the liveliness is mere appearance. No real portraits are drawn, rather a scenic apparatus is routinely played back.

Editions and translations

- Gunther Eigler (Ed.): Plato: Works in eight volumes. Vol. 7, 4th edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-19095-5 , pp. 255–443, 447–449 (reprint of the critical edition by Auguste Diès, 4th edition, Paris 1966, with the German translation by Friedrich Schleiermacher, 3. Edition, Berlin 1861).

- Otto Apelt (translator): Plato: Philebos . In: Otto Apelt (Ed.): Plato: All dialogues . Vol. 4, Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (translation with introduction and explanations; reprint of the 2nd, improved edition, Leipzig 1922).

- Dorothea Frede (translator): Plato: Philebos. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch and Carl Werner Müller , Vol. III 2). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-525-30409-9 .

- Ludwig Georgii (translator): Philebos . In: Erich Loewenthal (ed.): Plato: Complete works in three volumes . Vol. 3, unchanged reprint of the 8th, revised edition. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17918-8 , pp. 5-90.

- Rudolf Rufener (translator): Plato: Spätdialoge II (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 6). Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7608-3640-2 , pp. 3–103 (with an introduction by Olof Gigon pp. VII – XXVI).

literature

Overview representations

- Marcel van Ackeren : Knowledge of the good. Significance and continuity of virtuous knowledge in Plato's dialogues . Grüner, Amsterdam 2003, ISBN 90-6032-368-8 , pp. 258-274.

- Michael Erler : Platon ( Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , edited by Hellmut Flashar , volume 2/2). Schwabe, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-7965-2237-6 , pp. 253-262, 648-651.

- Peter Gardeya: Plato's Philebos. Interpretation and bibliography . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1993, ISBN 3-88479-833-2 .

Comments

- Seth Benardete : The Tragedy and Comedy of Life. Plato's Philebus. University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 1993, ISBN 0-226-04239-1 (English translation and commentary).

- Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch and Carl Werner Müller, Volume III 2). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-525-30409-9 .

- Justin Cyril Bertrand Gosling: Plato: Philebus. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1975, ISBN 0-19-872054-8 (English translation with introduction and commentary).

- Maurizio Migliori: L'uomo fra piacere, intelligenza e Bene. Commentario storico-filosofico al “Filebo” di Platone. Vita e Pensiero, Milano 1993, ISBN 88-343-0550-7 .

Investigations

- Eugenio E. Benitez: Forms in Plato's Philebus . Van Gorcum, Assen 1989, ISBN 90-232-2477-9 .

- Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon. Introduction à l'agathologie platonicienne . Brill, Leiden 2006, ISBN 90-04-15026-9 .

- Rosemary Desjardins: Plato and the Good. Illuminating the Darkling Vision . Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 90-04-13573-1 , pp. 12-54.

- Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being . State University of New York Press, Albany 1990, ISBN 0-7914-0260-6 .

- Gebhard Löhr: The problem of the one and many in Plato's "Philebos". Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1990, ISBN 3-525-25192-0 .

- Petra Schmidt-Wiborg: Dialectics in Plato's Philebos . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-16-148586-6 .

Collections of articles

- John Dillon , Luc Brisson (ed.): Plato's Philebus. Selected Papers from the Eighth Symposium Platonicum. Academia, Sankt Augustin 2010, ISBN 978-3-89665-479-3 .

- Monique Dixsaut (Ed.): La fêlure du plaisir. Études sur le Philèbe de Plato . 2 volumes, Vrin, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-7116-1378-X and ISBN 2-7116-1421-2 .

- Paolo Cosenza (Ed.): Il Filebo di Platone e la sua fortuna. Atti del Convegno di Napoli November 4-6, 1993 . D'Auria, Napoli 1996, ISBN 88-7092-117-4 .

Web links

- Philebos , Greek text after the edition by John Burnet , 1901

- Philebos , German translation after Friedrich Schleiermacher, edited

- Philebos , German translation after Ludwig von Georgii, 1869

Remarks

- ^ Plato, Philebos 16a – b.

- ↑ See on the figure of Socrates and her role Thomas Alexander Szlezák : Plato and the writing of philosophy , part 2: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 210–217; Reginald Hackforth : Plato's Examination of Pleasure , Cambridge 1958 (reprint of the 1945 edition), p. 7 f .; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 387-389; Georgia Mouroutsou: The metaphor of the mixture in the Platonic dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, p. 199 f.

- ^ Alfred Edward Taylor : Plato: Philebus and Epinomis , Folkestone 1972 (reprint of the 1956 edition), p. 11 f.

- ^ Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 95; Richard Goulet: Philèbe . In: Richard Goulet (Ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, p. 302.

- ↑ See on the role of Philebos Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , part 2: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 203 f.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, pp. 254–256. See Reginald Hackforth: Plato's Examination of Pleasure , Cambridge 1958 (reprint of 1945 edition), pp. 4-7; Justin CB Gosling, Christopher CW Taylor: The Greeks on Pleasure , Oxford 1982, pp. 157-164; Maurizio Migliori: L'uomo fra piacere, intelligenza e Bene , Milano 1993, pp. 352-357; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 390–394.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 11c, 26b.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 12b, 22c. Cf. Hans-Georg Gadamer: The idea of the good between Plato and Aristotle . In: Gadamer: Gesammelte Werke , Vol. 7, Tübingen 1991, pp. 128–227, here: 187.

- ^ Paul Friedländer: Platon , Vol. 3, 3rd, revised edition, Berlin 1975, pp. 288 f .; Reginald Hackforth: Plato's Examination of Pleasure , Cambridge 1958 (reprint of 1945 edition), p. 6; Hans-Georg Gadamer: The idea of the good between Plato and Aristotle . In: Gadamer: Gesammelte Werke , Vol. 7, Tübingen 1991, pp. 128–227, here: 186 f .; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, p. 34 f.

- ↑ Luc Brisson: Protarque . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 5, Part 2, Paris 2012, p. 1708; Michel Narcy: Plato. Philèbe . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 713–719, here: 714; Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 257; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 95; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 255.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 19b.

- ↑ Dorothea Frede pleads for this identification: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 95; on the other hand, Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 257 and Luc Brisson: Protarque . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 5, Part 2, Paris 2012, p. 1708.

- ^ Plato, Apology 20a-c; see. Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 58a – b.

- ↑ Aristotle, Physics 197b. See William David Ross (Ed.): Aristotle's Physics , Oxford 1936, p. 522.

- ↑ See also Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , part 2: The image of the dialectician in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 204–209.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 11a-12b. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 92-104.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 12c – 14b. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 105-110; Gebhard Löhr: The problem of one and many in Plato's “Philebos” , Göttingen 1990, pp. 12-21.

- ↑ Plato, Philebos 14c – 15a. Cf. Gebhard Löhr: The problem of the one and many in Plato's “Philebos” , Göttingen 1990, pp. 22-69.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 15a-16c. Cf. Constance C. Meinwald: One / Many Problems: Philebus 14c1-15c3 . In: Phronesis 41, 1996, pp. 95-103; Fernando Muniz, George Rudebusch: Plato, Philebus 15b: a problem solved . In: Classical Quarterly 54, 2004, pp. 394-405; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 21-23; Georgia Mouroutsou: The Metaphor of Mixing in the Platonic Dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 204–222; Gebhard Löhr: The problem of the one and many in Plato's “Philebos” , Göttingen 1990, pp. 69-100.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 15d – 17a. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 115-118; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 23-28; Georgia Mouroutsou: The Metaphor of Mixing in the Platonic Dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 222–247; Kenneth M. Sayre: Plato's Late Ontology , 2nd supplemented edition, Las Vegas 2005, pp. 118-126; Gebhard Löhr: The problem of one and many in Plato's "Philebos" , Göttingen 1990, pp. 178-188.

- ↑ For the example from music see Andrew Barker: Plato's Philebus: The Numbering of a Unity . In: Eugenio Benitez (ed.): Dialogues with Plato , Edmonton 1996, pp. 143–164, here: 146–161.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 17a – 20b. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 119-129; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 28-35; Georgia Mouroutsou: The Metaphor of Mixing in the Platonic Dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 247–260; Gebhard Löhr: The problem of the one and many in Plato's “Philebos” , Göttingen 1990, pp. 143–178, 188–193; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 144–159; Maurizio Migliori: L'uomo fra piacere, intelligenza e Bene , Milano 1993, pp. 104-123; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 146–169.

- ↑ See Michael Schramm: Dihärese / Dihairesis . In: Christian Schäfer (Ed.): Platon-Lexikon , Darmstadt 2007, pp. 92–95; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 369 f.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 20b-23b. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 130-137; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 164-199; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 169-184.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 23c-27c. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 138-156; Georgia Mouroutsou: The Metaphor of Mixing in the Platonic Dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 273–307; Gisela Striker : Peras and Apeiron , Göttingen 1970, pp. 41–76; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 201-258; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 184-211.

- ^ Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 13 Note 1.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 27c – 31b. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 157-165; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 258-285; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 211–221.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 31b-32b. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 297–303.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 32b-33c. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 303-313.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 33c – 35d. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 313-344.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 35d-37c. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 344–357.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 37c-38a. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 355–362.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 38a-41a. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 362-399.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 41a-42c. See Norman Mooradian: What To Do About False Pleasures of Overestimation? Philebus 41a5-42c5 . In: Apeiron 28, 1995, pp. 91-112; Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 186-189; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 399-412.

- ↑ On the question of who is meant here, see Malcolm Schofield: Who were οἱ δυσχερεῖς in Plato, Philebus 44 a ff.? In: Museum Helveticum 28, 1971, pp. 2–20, 181; Klaus Bringmann : Plato's Philebos and Herakleides Pontikos' dialogue περὶ ἡδονῆς. In: Hermes 100, 1972, pp. 523-530; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 268-271; Marcel van Ackeren: The knowledge of the good , Amsterdam 2003, p. 267, note 304.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 42c-44c. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 412–429.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 44c-45e. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 429–433.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 45e-50d. See Daniel Schulthess: Rire de l'ignorance? (Plato, Philèbe 48a-50e) . In: Marie-Laurence Desclos: Le rire des Grecs , Grenoble 2000, pp. 309-318; Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 198-208; Stefan Büttner: Plato's theory of literature and its anthropological justification , Tübingen 2000, pp. 96-100; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 64-67; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 433–448.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 50e-53c. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 209-212; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 67-74; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 449-491; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 295–306.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 53c-55c. See Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 213-216; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 493-506; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 306-318.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 55c-57e. See John M. Cooper, Plato's Theory of Human Good in the Philebus . In: Gail Fine (ed.): Plato , Oxford 2000, pp. 811-826, here: 815-820; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 507-523.

- ↑ Plato, Philebus 57e-59c. For the presentation of the dialectic in the Philebos see Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , part 2: The image of the dialectic in Plato's late dialogues , Berlin 2004, pp. 193-202; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 77-79.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 59d-61a.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 61a-64a. See Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 545–556.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 64a-65a. Cf. Damir Barbarić: Approaches to Plato , Würzburg 2009, pp. 99–112; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 556-577.

- ↑ On the function of reason and its position in the value system, see Christopher Bobonich: Plato's Utopia Recast , Oxford 2002, pp. 162–179.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 65a-67b. See Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 84-87; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, pp. 615-627; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 360–372.

- ^ Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 222 f .; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 259.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 255 f. Cf. Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 394–402.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 258; Peter J. Davis: The Fourfold Classification in Plato's Philebus . In: Apeiron 13, 1979, pp. 124-134, here: 129-132; Gisela Striker: Peras and Apeiron , Göttingen 1970, pp. 77-81; Marcel van Ackeren: The knowledge of the good , Amsterdam 2003, p. 259, note 250; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 49 f .; Kenneth M. Sayre: Plato's Late Ontology , 2nd supplemented edition, Las Vegas 2005, pp. 134-136; Henry Teloh: The Development of Plato's Metaphysics , University Park 1981, pp. 186-188; Eugenio E. Benitez: Forms in Plato's Philebus , Assen 1989, pp. 6, 59-91; Justin Gosling: Y at-il une Forme de l'Indéterminé? In: Monique Dixsaut (ed.): La fêlure du plaisir , Vol. 1, Paris 1999, pp. 43–59; Maurizio Migliori: L'uomo fra piacere, intelligenza e Bene , Milano 1993, pp. 450-457, 467-469.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 258 f. Julius M. Moravcsik, among others, argue for the implicit presence of the doctrine of ideas in the Philebus : Forms, nature, and the good in the Philebus . In: Phronesis 24, 1979, pp. 81-104; Robert Fahrnkopf: Forms in the Philebus . In: Journal of the History of Philosophy 15, 1977, pp. 202-207; Eugenio E. Benitez: Forms in Plato's Philebus , Assen 1989, pp. 3-6, 21-31, 39-42, 87-91, 129-132; Giovanni Reale: On a new interpretation of Plato , 2nd, expanded edition, Paderborn 2000, pp. 358–361, 450–454; Maurizio Migliori: L'uomo fra piacere, intelligenza e Bene , Milano 1993, pp. 75-84, 433 f., 450-457; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 7-11, 14-21; Margherita Isnardi Parente : Le idee nel Filebo di Platone . In: Paolo Cosenza (ed.): Il Filebo di Platone e la sua fortuna , Napoli 1996, pp. 205-219. Roger A. Shiner: Knowledge and Reality in Plato's Philebus , Assen 1974, pp. 11, 30, 34–37 (cautious; cf. Roger A. Shiner: Must Philebus 59a – c Refer to Transcendent Forms? In : Journal of the History of Philosophy 17, 1979, pp. 71-77); Russell M. Dancy: The One, the Many, and the Forms: Philebus 15b1-8 . In: Ancient Philosophy 4, 1984, pp. 160-193; Kenneth M. Sayre: Plato's Late Ontology , 2nd supplemented edition, Las Vegas 2005, pp. 174-185; Henry Teloh: The Development of Plato's Metaphysics , University Park 1981, pp. 176-188.

- ↑ Plato, Philebos 26d.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 258 f .; Michael Hoffmann: The emergence of order , Stuttgart 1996, pp. 113–125, 135–167, 189–207; Eugenio E. Benitez: Forms in Plato's Philebus , Assen 1989, pp. 99-108.

- ↑ See also Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 242-295; Seth Benardete: The Tragedy and Comedy of Life , Chicago 1993, pp. 175-186; Reinhard Brandt : True and false affects in the Platonic Philebus . In: Archive for the history of philosophy 59, 1977, pp. 1–18; Justin CB Gosling, Christopher CW Taylor: The Greeks on Pleasure , Oxford 1982, pp. 429-453; Marcel van Ackeren: The knowledge of the good , Amsterdam 2003, pp. 262–267; Karl-Heinz Volkmann-Schluck: Plato. The beginning of metaphysics , Würzburg 1999, pp. 100-105; Lloyd P. Gerson: Knowing Persons , Oxford 2003, pp. 253-262; Verity Harte: The Philebus on Pleasure: The Good, the Bad and the False . In: Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 104, 2004, pp. 113-130; Norman Mooradian: Converting Protarchus: Relativism and False Pleasures of Anticipation in Plato's Philebus . In: Ancient Philosophy 16, 1996, pp. 93-112; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Truth and Being in Plato's Philebus: A reply to Professor Frede . In: Phronesis 32, 1987, pp. 253-262.

- ↑ Maurizio Migliori: L'uomo fra piacere, intelligenza e Bene , Milano 1993, pp. 330, 466 f., 486-499, 535-537; Giovanni Reale: On a new interpretation of Plato , 2nd, expanded edition, Paderborn 2000, pp. 355–369, 413–444; Francisco L. Lisi: Bien, norma ética y placer en el Filebo . In: Méthexis 8, 1995, pp. 65-80, here: 76-79; Michael Hoffmann: The emergence of order , Stuttgart 1996, pp. 158–167; Georgia Mouroutsou: The metaphor of the mixture in the Platonic dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 200 f., 231–234, 282; Enrico Berti: Il Filebo e le dottrine non steps di Platone . In: Paolo Cosenza (ed.): Il Filebo di Platone e la sua fortuna , Napoli 1996, pp. 191-204. Cf. Gisela Striker: Peras and Apeiron , Göttingen 1970, pp. 45 f.

- ↑ See Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 259 (cautiously agreeing); Kenneth M. Sayre: Plato's Late Ontology , 2nd, supplemented edition, Las Vegas 2005, pp. 136–155 (agreeing; Cynthia Hampton: Pleasure, Knowledge, and Being , Albany 1990, pp. 98–101); Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 403-417 (skeptical); Eugenio E. Benitez: Forms in Plato's Philebus , Assen 1989, p. 59 (negative); Georgia Mouroutsou: The metaphor of the mixture in the Platonic dialogues Sophistes and Philebos , Sankt Augustin 2010, p. 282 (negative).

- ↑ See also Thomas M. Tuozzo: The General Account of Pleasure in Plato's Philebus . In: Journal of the History of Philosophy 34, 1996, pp. 495-513.

- ↑ Mark Moes: Plato's Dialogue Form and the Care of the Soul , New York 2000, pp. 113-161.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 253 f .; Michel Narcy: Plato. Philèbe . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 713–719, here: 713 f. Robin AH Waterfield: The Place of the Philebus in Plato's Dialogues advocates early dating . In: Phronesis 25, 1980, pp. 270-305. Cf. Gerard R. Ledger: Recounting Plato , Oxford 1989, pp. 198 f .; Holger Thesleff : Platonic Patterns , Las Vegas 2009, pp. 344–346.

- ^ Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 385; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 254.

- ^ Corpus dei Papiri Filosofici Greci e Latini (CPF) , Part 1, Vol. 1 ***, Firenze 1999, pp. 285-289, 508-512.

- ↑ Oxford, Bodleian Library , Clarke 39 (= "Codex B" of the Plato textual tradition).

- ↑ See for example Robin AH Waterfield: On the text of some passages of Plato's Philebus . In: Liverpool Classical Monthly 5, 1980, pp. 57-64.

- ↑ See e.g. B. Franz Dirlmeier : Aristoteles: Nikomachische Ethik , 8th edition, Berlin 1983, pp. 277, 499-501, 575 f. Cf. Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, pp. 418-426.

- ↑ Theophrast, Fragment 556, ed. by William W. Fortenbaugh among others: Theophrastus of Eresus. Sources for his Life, Writings, Thought and Influence , Vol. 2, Leiden 1992, pp. 380 f.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3.57 f.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Demosthenes 23.4.

- ↑ Heinrich Dörrie , Matthias Baltes : The Platonism in antiquity , Vol. 3, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1993, p. 198.

- ↑ Plato, Sophistes 254b-255e.

- ↑ See Heinrich Dörrie, Matthias Baltes: Der Platonismus in der Antike , Vol. 4, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1996, pp. 106-109, 372; Gerd Van Riel (Ed.): Damascius: Commentaire sur le Philèbe de Platon , Paris 2008, pp. XII – XVII. For general information on Plutarch's Philebos reception, see Renato Laurenti: Il Filebo in Plutarco . In: Paolo Cosenza (ed.): Il Filebo di Platone e la sua fortuna , Napoli 1996, pp. 53-71.

- ↑ Porphyrios, Vita Plotini 20: 41-43.

- ↑ Heinrich Dörrie, Matthias Baltes: The Platonism in antiquity , Vol. 3, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1993, p. 198 and note 8.

- ↑ Dominic O'Meara gives an overview: Lectures néoplatoniciennes du Philèbe de Platon . In: Monique Dixsaut (ed.): La fêlure du plaisir , Vol. 2, Paris 1999, pp. 191-201. See Gerd Van Riel (Ed.): Damascius: Commentaire sur le Philèbe de Platon , Paris 2008, pp. XXXII – LXVIII.

- ↑ See Gerd Van Riel (ed.): Damascius: Commentaire sur le Philèbe de Platon , Paris 2008, pp. XVII – XXV, LXXXVIII – CI and the references to relevant passages in Pierre Hadot : Plotin: Traité 38 , Paris 1988, p 141-163, 169 f .; see. in Hadot pp. 24 f., 29, 299 f., 311-324, 330 f., 334-336.

- ↑ Prolegomena to the Philosophy of Plato 26, ed. von Leendert G. Westerink : Prolégomènes à la philosophie de Platon , Paris 1990, p. 39.

- ↑ John M. Dillon (ed.): Iamblichi Chalcidensis in Platonis dialogos commentariorum fragmenta , Leiden 1973, pp. 100-105; see. Pp. 257-263.

- ↑ Damascios, Vita Isidori 42.

- ↑ Gerd Van Riel (ed.): Damascius: Commentaire sur le Philèbe de Platon , Paris 2008, pp. I f., CXXX – CLXVIII, CLXXVI – CLXXIX. On the Neoplatonic Philebos commentary, see Heinrich Dörrie, Matthias Baltes: Der Platonismus in der Antike , Vol. 3, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1993, pp. 198 f.

- ↑ See on Ficino's translation Ernesto Berti: Osservazioni filologiche alla versione del Filebo di Marsilio Ficino . In: Paolo Cosenza (ed.): Il Filebo di Platone e la sua fortuna , Napoli 1996, pp. 93–171 and the introduction by the editor Michael JB Allen to his commentary: Marsilio Ficino: The Philebus Commentary , Berkeley 1975, p. 1-22.

- ^ Judith P. Jones: The Philebus and the Philosophy of Pleasure in Thomas More's Utopia . In: Moreana 31/32, 1971, pp. 61-69.

- ^ Friedrich Schleiermacher: Philebos. Introduction . In: Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher: About the philosophy of Plato , ed. by Peter M. Steiner, Hamburg 1996, pp. 303-312, here: 303.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 256; Sylvain Delcomminette: Le Philèbe de Platon , Leiden 2006, p. 16 f .; Dorothea Frede: Plato: Philebos. Translation and Commentary , Göttingen 1997, p. 379 f.

- ↑ See on the appreciation of the theory of the comic Salvatore Cerasuolo: La trattazione del comico nel Filebo . In: Paolo Cosenza (ed.): Il Filebo di Platone e la sua fortuna , Napoli 1996, pp. 173-190.

- ↑ Pierre Garniron, Walter Jaeschke (Ed.): Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Lectures on the History of Philosophy , Part 3, Hamburg 1996, p. 30 f.

- ↑ See Hermann Krings : Genesis und Materie . In: Hartmut Buchner (Ed.): FWJ Schelling: “Timaeus” (1794) , Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1994, pp. 115–155, here: 117–120, 123, 127 f., 140–142, 145; Michael Franz : Schelling's Tübinger Platon-Studien , Göttingen 1996, pp. 258 f., 269–276, 279.

- ^ Paul Natorp: Platos Ideenlehre , Hamburg 1994 (text of the 2nd edition from 1921), pp. 312–349, here: 313.

- ^ Paul Natorp: Platos Ideenlehre , Hamburg 1994 (text of the 2nd edition from 1921), pp. 343-345.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Gadamer: Plato's dialectical ethics . In: Gadamer: Gesammelte Werke , Vol. 5, Tübingen 1985 (first published in 1931), pp. 3–163.

- ^ Robert J. Dostal: Gadamer's Platonism and the Philebus: The Significance of the Philebus for Gadamer's Thought . In: Christopher Gill, François Renaud (Eds.): Hermeneutic Philosophy and Plato. Gadamer's Response to the Philebus , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 23–39, here: 27, 29–33.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Gadamer: Plato's dialectical ethics . In: Gadamer: Gesammelte Werke , Vol. 5, Tübingen 1985 (first published in 1931), pp. 3–163, here: 118.

- ↑ Walter Mesch: False lust as a groundless hope. Gadamer and the newer Philebos interpretation . In: Christopher Gill, François Renaud (Eds.): Hermeneutic Philosophy and Plato. Gadamer's Response to the Philebus , Sankt Augustin 2010, pp. 121-137, here: 131 f.

- ↑ See on Gadamer's Philebos reception the articles in the collection of articles Hermeneutic Philosophy and Plato edited by Christopher Gill and François Renaud . Gadamer's Response to the Philebus , Sankt Augustin 2010 (overview in the editor's introduction, pp. 9-20).

- ↑ Herbert Marcuse: On the Critique of Hedonism . In: Herbert Marcuse: Schriften , Vol. 3, Frankfurt am Main 1979, pp. 263-265.

- ↑ Donald Davidson: Plato's Philebus , New York / London 1990 (text of the dissertation with a new introduction), Preface and p. 13 f. the introduction.

- ^ Plato, Philebos 38e – 39e. Jacques Derrida: Dissemination , Vienna 1995 (German translation of the original edition from 1972), p. 193 ff.

- ^ William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 5, Cambridge 1978, pp. 238-240.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Volkmann-Schluck: Plato. The beginning of metaphysics , Würzburg 1999, p. 93.

- ^ Friedrich Schleiermacher: Philebos. Introduction . In: Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher: About the philosophy of Plato , ed. by Peter M. Steiner, Hamburg 1996, pp. 303-312, here: 311 f.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: Platon. His life and his works , 5th edition, Berlin 1959 (1st edition Berlin 1919), p. 497 f.

- ^ Lecture recording in: Friedrich Nietzsche: Werke. Critical Complete Edition , Department 2, Vol. 4, Berlin 1995, p. 139.

- ^ Paul Friedländer: Platon , Vol. 3, 3rd, revised edition, Berlin 1975, p. 286 f.