Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel

Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel (born July 11, 1659 in Greußen an der Helbe , † November 17, 1707 in Dresden ) was a German polyhistor , historiographer and numismatist .

Life

Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel, son of the deacon Jacob Tentzel and Sophie Elise Leyser, grew up in Arnstadt . On his mother's side, he was a descendant of the Wittenberg theology professor Polycarp Leysers and the painters Lucas Cranach the Elder and Lucas Cranach the Younger . In 1677 he moved to the University of Wittenberg , where he studied theology , philology and history . From 1673 he was a research assistant in the Philosophical Faculty , published his first writings and corresponded with high-ranking scholars such as Johann Samuel Adami .

In 1689 he broke off work in Wittenberg in order to settle his father's estate in Arnstadt. From there he went as a teacher to the Illustre grammar school in Gotha and was entrusted in 1692 by Duke Friedrich II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg with the organization of the princely coin collection . In 1694 he was appointed as successor to Caspar Sagittarius in the office of court historian of the dukes of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.

When in 1695 farmers in Tonna found the bones of a forest elephant who had died a hundred thousand years ago while digging for sand , the ducal personal physician Raab and later the “Scholars Collegium Medicum” in Gotha took the view that it was a mineral structure. Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel, on the other hand, proved in his work "Epistola de sceleto elephantino", published in 1696, that they came from an elephant. However, the idea of a drastic climate change was not yet capable of consensus; Even the correspondence that Tentzel had with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz on this matter did not bring the longed-for scientific recognition. It was not until 1699, with a second discovery, that Tentzel's declaration finally prevailed.

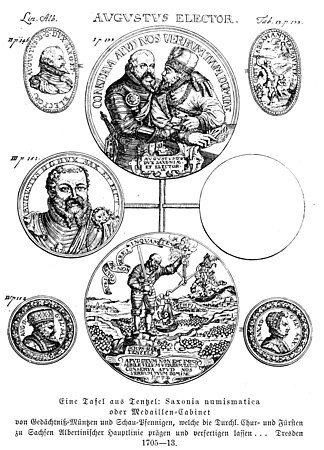

Around 1700, Tentzel turned down a job as archivist at the imperial court in Vienna because this would have required a transfer to the Catholic Church. In 1702 he finally accepted the call to the court of August the Strong in Dresden , which gave him the title of councilor and appointed him royal and electoral historiographer and archivist . But just one year later, in 1703, Tentzel lost this position due to intrigues at court and lived in poverty until the end of his life. Nevertheless, in 1705 he published the first part of his Saxonia Numismatica . He died on November 17, 1707 at the age of 48. His numismatic work was continued by Christian Wermuth and published until 1714.

meaning

Tentzel is one of the most productive scholars of his time, working on a wide variety of subject areas and describing the close connection between medal art and historiography . Medals and commemorative coins were important additions to the archival sources for him . He encouraged the Saxon princes to create coin cabinets based on the state archives . He also dealt intensively with the history of medals in Saxony. He wrote his Saxonia Numismatica Lineae Ernestinae et Lineae Albertinae (Saxon Medal History of the Ernestine and Albertine Lines) in German and Latin so that it could also be read outside of Germany. 1285 medals and commemorative coins were depicted and described, the reasons for the issues were explained and the historical and genealogical connections were explained in detail. It is one of the most extensive historical collections of material from this period.

Works

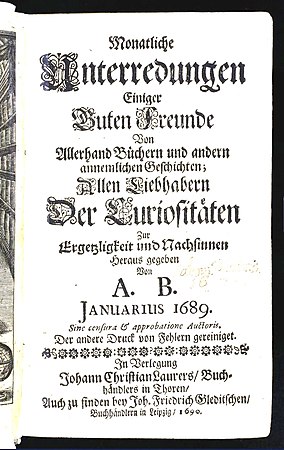

- Monthly conversations with a few good friends about all kinds of books and other similar stories; Edited by AB , Thorn and Leipzig 1689–1698 to all lovers of curiosities for greediness and reflection

- Epistola de sceleto elephantino , Jena 1696

- Saxonia numismatica lineae Ernestinae et Albertinae , Gotha 1705–1714

- The Histoire Métallique of the Saxon electors and dukes in the mirror of the treatises , in: Paul Arnold: European numismatic literature in the 17th century , Wiesbaden 2005, pp. 311–326

literature

- Franz Xaver von Wegele : Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 37, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1894, p. 571 f.

- Tentzel, Wilhelm Ernst. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 42, Leipzig 1744, columns 901-906.

- Wolfgang Steguweit : Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel . Epilogue to the unchanged photomechanical reprint of Saxonia Numismatica, 1713–1714, Berlin 1981–82, the same, enriched with illustrations, in: Numismatical Hefte 1, Kulturbund der DDR, VI. District coin exhibition, Römhild 1981, pp. 18–38

- Christian E. Dekesel: European numismatic literature in the 17th century , Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005

- Tyll. Kroha: Large Lexicon of Numismatics , Gütersloh 1997

- Walther Killy : Literature Lexicon . Authors and works in the German language, Gütersloh 1988–1991

Web links

- Correspondence between Leibniz and Tentzel about the discovery of a forest elephant (in English translation)

- Ernst Wilhelm Tentzel and the history of medals in Saxony

- Literature by and about Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel in the German Digital Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Writings of the Association for Saxony-Meiningische Geschichte and Landeskunde 53, Hildburghausen 1906, p. 32.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tentzel, Wilhelm Ernst |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tentzelius, Wilhelmus Ernestus; Tenzelius, Wilhelmus Ernestus; Tenzelius, Guilelmus Ernestus; Tenzel, Wilhelm Ernst |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German polyhistor, numismatist, archivist, historiographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 11, 1659 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Greetings |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 17, 1707 |

| Place of death | Dresden |