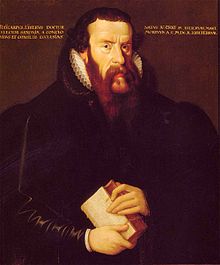

Polykarp Leyser the Elder

Polycarp (von) Leyser the Elder , (born March 18, 1552 in Winnenden ; † February 22, 1610 in Dresden ; also Polycarp Leyser I ) was a Lutheran theologian , superintendent of Braunschweig , general superintendent of the Saxon spa district , professor of theology in Wittenberg , senior court preacher and consistorial councilor of Saxony .

Life

Educational path

Polycarp's father, Magister Kaspar Leyser (* July 20, 1526; † late 1554 in Nürtingen), was a pastor in Winnenden, later in Nürtingen . At the side of Jacob Andreae, he advocated placing church discipline entirely in the hands of the pastors, which would have resulted in the establishment of parish consistories. Both were in contact with Johannes Calvin , who was, however, reserved about their ideas. At least they managed to get the approval of Duke Christoph von Württemberg . At the instigation of Johannes Brenz , however, this request failed, who warned against giving up the church discipline centralized in the Württemberg Territorial Church.

Polykarp Leyser's mother Margarethe was a daughter of the Tübingen merchant Johannes Entringer and a sister-in-law of Jakob Andreaes. After Kaspar Leyser died in 1554, his widow soon married Lucas Osiander the elder . In 1556 the family moved to Blaubeuren , where Leyser attended the convent school and grew up with the three sons of his stepfather. In 1562 he moved to the Stuttgart pedagogy. After his mother's death in 1566, his stepfather sent him to the University of Tübingen , where he studied Protestant theology as a ducal scholarship holder .

In Tübingen he met Aegidius Hunnius , with whom he soon became a deep friend. In 1570 he acquired the academic degree of a master’s degree and shortly afterwards became repetitee . During this time he was influenced theologically by Jacob Heerbrand , Andreae and Dietrich Schnepf . Leyser excelled through excellent exam results. Therefore, Andreae had him publicly dispute the doctrine of justification in 1572 . At the beginning of 1573 he was ordained and he took over a pastorate in Göllersdorf in Lower Austria . Here he came into contact with the imperial councilor and hereditary assistant Michael Ludwig von Puchheim (1512–1580), who introduced him to court life under Maximilian II . Immediately they became aware of him in Graz and wanted to win him over to work there, but Osiander and Puchheim advised against it . Instead he went back to Tübingen, where he received his doctorate in theology on July 16, 1576, together with his friend Hunnius . Initially, Leyser had only limited career prospects, but that soon changed.

Wittenberg time

In Wittenberg , the disputes over the overthrow of the Philippists had led to drastic personnel changes at the university since 1574. These were sometimes accompanied by tumultuous expressions of displeasure against the teachers. After the death of the former head of the theological faculty, Kaspar Eberhard, in October 1575, David Chytraeus was initially asked to take over the general superintendent's position in Wittenberg, but he refused. Thereupon Leyser was called to Wittenberg as general superintendent in November of the same year. The rectory at the Wittenberg town church was connected to this position .

Leyser was initially loaned to Elector August von Sachsen by his sovereign Duke Ludwig von Württemberg for two years . On January 20, 1577, he gave a trial sermon in Dresden. On February 3rd it was ceremoniously introduced in Wittenberg. Leyser then went back to Austria via Dresden to “pick up his things”. On May 12th he was back in Wittenberg and now took up his official duties. The fact that a 25-year-old suddenly stood in the highest ecclesiastical office in Wittenberg without first being noticed theologically in Saxony caused a general sensation. When he became a professor at the theological faculty on June 8, 1577 and even a member of the consistory on November 20, 1577, some people accused him of nepotism.

However, Leyser's soothing attitude in the expulsion of the Saxon crypto-calvinists and in the reorganization of the Wittenberg University was able to acquire such merit that his critics soon faded into the background. Above all, he benefited from rhetorical skills and an undemanding and reliable manner. These increased his popularity among students, including Philipp Nicolai and Johann Arndt . Leyser's abilities were also evident in the development of the concord formula , which appeared in the 1580 Book of Concords. In doing so, he developed close contacts to Martin Chemnitz and Nikolaus Selnecker . Together with the latter, he was commissioned to obtain the signatures of a commission convened for this purpose in Electoral Saxony for the concord formula, which he himself had signed on June 25, 1577 as the first clergyman of the Kurkreis.

He soon took part in the important theological conventions in Saxony and proved himself to be a recorder of them. An outsider was always a thorn in the side of those who were envious of Wittenberg. In order to remove the foundation from them, he married the local Elisabeth Cranach in March 1580. The wedding, which took place in the Wittenberg town hall, was overshadowed by student riots and extravagant drinking bouts, which the responsible authorities were to occupy later.

In 1581 we find Leyser again as a visitor to the Saxon spa districts , where he mainly devoted himself to the lower school system and the princely schools in Meißen, Schulpforta and Grimma. During this time, he only published funeral sermons and disputations. Above all, however, he was troubled by the resistance to the concord formula. During this time Tilemann Hesshus was his bitter opponent in the implementation of the ubiquity theory . The disputes were carried out at colloquia, for example in Quedlinburg in 1583 , where he witnessed the last big appearance of his former mentor Chemnitz. When the latter stepped down from the office of the Braunschweig superintendent on September 9, 1584, the Braunschweiger wanted to sign Leyser as the new superintendent. However, he declined on Selnecker's advice, as he felt obliged to his employer August von Sachsen.

When August 1586 died - Leyser gave him the funeral sermon - the tide turned with the arrival of the new Elector Christian I , who tended towards Calvinism and crept through it. In this way, he released the pastors from the obligation to sign the concord formula at the ordination, which was also extended to the teaching staff. Leyser, who was considered the most important representative of Concord Lutheranism under August of Saxony, was also increasingly exposed to hostility from Nikolaus Krell and Johann Major , who exerted increasing influence on university and consistorial affairs. Leyser was so angry about this hostility that he warned the students against acquiring a master's degree under major. When the Calvinist Matthias Wesenbeck was buried in the castle church at the feet of Martin Luther and Leyser claimed in his funeral sermon that he had renounced Calvinism before his death and had died Lutheran, there was an uproar that Leyser continued into his Braunschweig days should accompany.

Brunswick time

In Braunschweig there had been theological arguments with the city superintendents there in 1587, so that Leyser was again contacted to clarify the matter by coming. Krell supported this request to get rid of his unpleasant opponent in Wittenberg, Saxony, and obtained the consent of the Elector, who was not exactly happy about Leyser's departure, but nevertheless granted his dismissal in August 1587. After Leyser went to Braunschweig for the first time in September, his final departure in December was accompanied by protests that saw his departure as an advance of Calvinism.

On December 17, 1587 Leyser gave his inaugural sermon in Braunschweig at the St. Aegidien Church and became coadjutor of the superintendent, whom he immediately ousted and proved to be an energetic defender of the theory of ubiquity. The official appointment took place on December 22nd. During his time in Brunswick, Leyser enforced that the concord formula became part of the local church order. From Braunschweig he had to follow how his achievements in Electoral Saxony were consistently reversed by the Calvinists. Thus, the church supervision of the princely schools was restricted, new church and school regulations as well as new consitorial regulations were issued and the senior consonsory in Dresden was repealed. The Lutherans were driven out of their offices and representatives of Calvinism were installed. Leyser, who wanted to end this hustle and bustle, therefore traveled to Lüneburg, Hamburg, Lübeck, Wismar and Rostock to look for allies for his fight against Calvinism.

In 1591/92 Leyser appeared in the dispute over the abolition of exorcism at baptism and on this issue especially argued with his Wittenberg successor Urban Pierius . When the baptismal rites in the Principality of Anhalt-Bernburg were changed anyway, Leyser held a fiery defense of Luther's baptismal book . The Calvinist theologians of Anhalt responded with an attack on Chemnitz, who had already died. Leyser reacted with a very emotional “salvation of honor, faith and confession of Dr. Martini Chemniti [...] who was blasphemed by the adherents and Calvinists as if he had fallen away from his confession before his end ”(Magdeburg 1592) and found extensive support in the circles of Braunschweig theologians.

In the meantime the situation had changed again with the death of Christian I of Saxony. Friedrich Wilhelm I (Sachsen-Weimar) had taken over the official business for the still underage Christian II of Saxony and changed the religious policy back to the lines of the former Elector August. As a result, the Calvinist forces lost their influence in Saxon religious policy. They quickly resorted to Leyser again and in October 1591, Georg Mylius suggested to him to return to the Electoral Saxon church service. The Calvinist general superintendent was deposed and Leyser's brother-in-law Augustin Cranach was sent to Braunschweig to persuade Leyser to return to Wittenberg.

However, Leyser remained in Braunschweig, and he also turned down an offer from the Leipzig general superintendent with the pastor's office at St. Nicolaikirche . In the summer of 1592 negotiations began with the representatives of Wittenberg and Braunschweig about dismissal from the Braunschweig service. Since the citizens of Brunswick saw Leyser's emigration as an intrigue of his opponents, there were riots. In April 1593 it was agreed that Leyser should go to Wittenberg for two years and keep the Braunschweig superintendent on the side. Leyser had to vow to return to Braunschweig in April 1595 and visit the entire church once a year. In order to ensure the fulfillment of these agreements, he had to leave his household effects in the city.

On May 21, 1593, Leyser gave his second inaugural address as Wittenberg professor and general superintendent. In it he looked back on the five years of "exile" that had lay behind him and thanked God for his loyalty. In this sense, Leyser faithfully kept the promises he had made to the Braunschweig residents: he made his first visit at the end of June, the next followed in autumn.

Leyser was soon drawn into the dispute with Samuel Huber , whom he initially supported, as dean of the theological faculty . Huber spread that the concord formula was crypto-calvinistic and advocated his doctrine of "universalism of grace". Leyser and especially his friend Aegidius Hunnius the Elder , who also worked at the Wittenberg University, called a colloquium . However, all attempts at mediation failed in the dispute with Huber, so that he was dismissed from the university in 1594 and from the Electoral Saxon service in 1595. Leyser went to Braunschweig in April 1594 to make another visitation there. At the instigation of the Electress Sophie , Leyser was called to Dresden as senior court preacher. It took some negotiations to get the Braunschweig council to see that Leyser should go. On June 2, 1594, Leyser gave his two-hour farewell sermon. Three days later he left for Dresden.

Dresden time

In July 1594, Leyser took up his post as first court preacher in Dresden and was thus given regional bishop rights for Saxony. As a Lutheran-Orthodox court preacher, he embodied the typical features of his basic theological position. He anchored this in a court preacher's mirror, in which he sets out his self-image of the activity of a court preacher as a model for all successors in office. In terms of content, Leyser assumes the emphasis on pure teaching in scripture and confession, which in practical terms leads to the necessity of preaching in the face of the manifold temptations and sins, especially at court.

Leyser extensively rejects the accusation of alleged wealth in the court preaching office. Church and school must have the necessary financial resources, for which he repeatedly makes entries and also considers fines to be necessary. Leyser clearly emphasizes the independence of the clergy. In doing so, he countered the accusation, which was often raised against the court preachers in particular, that they wanted to influence political affairs in their office. Because Leyser himself was also accused of playing the role of a "Dreßnische Bapstes". The priests, it was said, wanted to "dominate" too much, one foot on the pulpit and the other on the chancellery. With the skilful reference to the mixed, half spiritual, half secular affairs in church and school matters, he emphasizes the responsibility of court preachers in this area, although a spiritual person only has to deal with spiritual matters. In connection with the strict adherence to the traditional church ordinances demanded by Leyser, the struggles, especially with the landed gentry, who refuse to submit to the orders of the alleged Dresden Pope - for example with child baptisms - are described in detail.

With these rules, Leyser clearly wanted to set a general standard for court preachers, especially for young preachers who should consider “how a Hoff preacher had such an arduous, caring job in his profession.” With a sharp criticism, probably especially in view on Calvinist court preachers, Leyser concludes his court preacher mirror: “How should it go to those / who so blindly burst into the court preacher / don't think about it once / what care it is to do / sit from one midnight bit to another / lie down and up with of society / and make it so unsavory / that your ears hurt / who only hears it? "

This spirit of a self-confident Lutheran court preacher is also expressed in Leyser's regent and state parliament sermons in Dresden, in which the understanding of authority and the criticism of authority of older Lutheranism are summarized in a particularly characteristic way. In direct reference to Luther's understanding of authority in the authoritative document of 1523 and above all in his interpretation of the 101st Psalm of 1535, Leyser emphasized the deep connection between divine dignity and the high responsibility of the magisterial office. His considerable criticism of the specific actions of the authorities can only be understood from this context.

In his political sermon at the Dresden court, Leyser is primarily concerned with the independence of the church and the spiritual office in the early modern territorial state . In the court preaching office he tries to have a decisive influence on the organization of public affairs, above all on the church order, with fundamental instruction and concrete admonitions. With the punishing sermon he criticizes the authorities, not only reprimands personal behavior, but also emphasizes the political and, above all, social responsibility of the rulers and their court officials. It corresponds to the strict standard that Leyser sets for himself and for all preachers, especially court preachers. Leyser takes the ethical criteria and the illustrative material for his understanding of authority with the whole Lutheran orthodoxy from the pious kings of the Old Testament. By contrasting his advice with that of Chancellor Nikolaus Krell, the Lutheran court preacher anticipates the incompatibility of fear of God and reason of state with which, after the Thirty Years' War, Lutheran theologians fight against the destructive forces in the understanding of rule of the early absolutist state. His understanding of the character of a Lutheran statesman is reflected in the funeral speech for the Electorate Chancellor David Peifer (1602). ( A Christian sermon , Matthes Stöckel, Dresden 1602)

From Dresden he not only dealt with the differing ideas, but also had to clarify questions of the Church within Saxony in connection with the office of court preacher. He carried out visitations himself, introduced the general superintendents to their office and worked on the university regulations in Saxony. In his will, he bequeathed money to students to help them study and was paid out annually on the days of St. Polycarp (January 26) and St. Elizabeth (November 19). For his services and those of his ancestors to the House of Austria, he was raised to the hereditary nobility by Emperor Rudolf II on December 22, 1590 in Prague. After a long illness he died in Dresden. His solemn burial took place on March 1, 1610 in the local Sophienkirche .

Leyser as an author

Leyser, who as a theologian also dealt literarily with the disputes of his time in the course of his life and thereby maintained an extensive correspondence, is far from being fully scientifically processed. His great-grandson Polykarp Leyser III. published an extensive selection of letters in Sylloge epistolarum in 1706 , which presumably only represents the tip of the potential still to be explored, with 200 letters from him and 5,000 to him. Furthermore, extensive funeral sermons are known from him, which broaden the spectrum of the preacher in the time of the Concordian Lutheranism and his context-sensitive concerns. His theological explanations comprise more than 60 writings and thus form a further research stock that can provide additional information about the so far insufficiently researched area of the networks of Lutheranism in the area of denomination.

Fonts

For a complete overview of the surviving prints, see the list of prints from the 16th century published in the German-speaking area (VD 16)

Conclusion

Leyser, who was encouraged by his father, his uncle Andreae and later by his stepfather Osiander, also found a deeply rooted standpoint in Lutheran orthodoxy through his teacher Chemnitz. In the troubles of his day, he was the one who established this orthodoxy. One is amazed at his creative power at the Loci theologici (1591/92), the Harmonia evangelica (1593), Postilla (1593) and De controversiis iudicium (1594). His theological point of view was sparked by the dispute over the Electoral Saxon (crypto) Calvinism, the exorcism dispute, the dispute over Lutheran Christology and the Huber dispute. Leyser has undoubtedly counted among the key figures of the north and central German Concord Lutheranism. Last but not least, he was exposed to constant hostility and was attacked as Pope of Dresden in pamphlets in the then not insignificant part of Saxony for Germany. As one of the key contributors to the formula of concord , Leyser also campaigned for the defense of Lutheran orthodoxy, against Calvinism and the Roman Church. On the orders of the elector, he accompanied the work of several convents on the Book of Concord . He advocated limiting the number of sponsors to three. However, its work has by no means been fully explored. New traces of evidence still open up a wide spectrum that has yet to be recorded.

family

Leyser, who, according to the sources, came from the influential Austrian noble family of the Leysers , married Elisabeth Cranach on May 17, 1580 (born December 3, 1561 in Wittenberg; † September 16, 1645 ibid). She was the youngest daughter of the important Wittenberg painter and former mayor of Wittenberg Lucas Cranach the Younger and his second wife Magdalena Schurff (1531-1606), a daughter of Augustin Schurff . The apparently happy marriage lasted almost 30 years and resulted in five sons and eight daughters.

After the younger Cranach's death, Leyser inherited his house at today's Schloßstraße 1 and erected the epitaph that still hangs in the Wittenberg town church.

The children of Leyser were:

- Magdalena Leyser (born November 29, 1581 in Wittenberg; † April 2, 1602 in Dresden), married October 31, 1599 in Dresden with the electoral Wittums chamber master, councilor and secret secretary in Dresden Caspar Schreyer (* Wunsiedel; † June 14 1602 in Dresden)

- Lucas Leyser (born May 2, 1583 in Wittenberg, † August 23, 1599 in Wittenberg), student

- Elisabeth Leyser (born January 12, 1585 in Wittenberg; † September 26, 1635 in Leipzig), married on January 26, 1605 Michael Wirth (October 14, 1571 - May 25, 1618), councilor of appeals in Leipzig, professor at the University of Leipzig

- Polykarp Leyser II (born November 20, 1586 in Wittenberg, † January 15, 1633 in Leipzig), married Sabina Volckmer, daughter of Nikolaus Volkmar, mayor and bookseller in Leipzig, on October 31, 1615

- Friedrich Leyser Erbsass auf Broda (* approx. 1590 in Braunschweig; † July 19, 1645 in Eilenburg ), married to Dorothea Schmidt, daughter of the magistrate in Torgau Georg Schmidt, received her doctorate in theology in Jena in 1617, chief preacher in Dresden, superintendent in Eilenburg, wrote: Disp. inaug. de dicto Apostolico , Rome. 4. 22. 23. as well as some funeral sermons. Friedrich L. had six sons and two daughters, of whom we know: Polycarp Leyser (1619–1636), Georgius Leyser (born August 17, 1621 in Eilenburg; † November 21, 1621 in Eilenburg), Friedrich Leyser (1623–1636) , Magister Wilhelm Leyser, Elisabeth Leyser, married on November 16, 1645 in Eilenburg to Joachim Buchholtz, Lic. Theol, Superintendent in Eilenburg, and Christian Leyser, Lucas Leyser (* August 22, 1624 in Eilenburg; † June 22, 1635 ibid) and Christina Dorothea Leyser.

-

Wilhelm Leyser I (born October 26, 1592 in Braunschweig; † February 8, 1649 in Wittenberg)

- Marriage to Regina Tüntzel (* July 22, 1602 in Leipzig; † December 30, 1631 in Wittenberg), the daughter of the imperial Count Palatine a. electoral Saxon privy councilor Gabriel Tüntzel († December 21, 1645 Dresden) and his wife Catharina Schilter (* December 17, 1576 in Leipzig, † March 22, 1628 in Dresden)

- Marriage to Katharina Bose (* December 15, 1615 in Leipzig, † June 30, 1677 in Wittenberg), daughter of councilor and merchant Caspar Bose († July 5, 1676) and his wife Katharina Schreider (1578–1620). Married II on February 17, 1663 in Wittenberg to Caspar Ziegler

- Caecilie Leyser (born November 2, 1588 in Braunschweig, † April 19, 1665 in Wittenberg), married to Erasmus Unruh since 1605

- Magaretha Leyser (born February 22, 1594 in Wittenberg, † January 14, 1662 in Leipzig), married on October 28, 1611 in Leipzig the lawyer and assessor at the Schöppenstuhl in Leipzig Enoch Heiland (also: Heyland), whose son Polycarp Heyland father of Auguste Christine, the wife of Christian Thomasius (1655-1728).

- Sophia Leyser

- Marriage on February 9, 1613 to Dr. med. Bartholomäus Krüger (born April 30, 1579 in Danniko near Magdeburg, † May 23, 1613 in Wittenberg)

- Marriage on February 3, 1617 to David Faber (also Fabri), Dr. med. and district physician

- Anna Maria Leyser (born February 18, 1597 in Dresden, † June 6, 1618 in Wittenberg), engaged to Ernst Stisser, but died before the wedding

- Dorothea Leyser († April 28, 1667 in Leipzig), married to Johann Jacob Reiter , Dr. med. and professor in Leipzig

- Euphrosina Leyser

- Marriage on November 5, 1622 to Andreas Großhenning , Dr. theol., professor in Rostock

- Married September 1627 with Leonhard Rechtenbach, Dr. theol., Superintendent in Eisleben

- Christian Leiser (* 1600 in Dresden; † March 30, 1602 in Dresden)

literature

- Georg Christian Bernhard Pünjer : Leyser, Polykarp (I.) . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, pp. 523-526.

- Theodor Mahlmann: Leyser, Polycarp. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , p. 436 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Karl Friedrich Ulrichs : LEYSER, Polycarp d. Ä .. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 5, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-043-3 , Sp. 3-7.

- Real Encyclopedia for Protestant Theology and Church . Volume 11. 3rd edition. Page 431.

- Leyser, Polycarpus, a Lutheran theologian. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 17, Leipzig 1738, column 728-730.

- Walter Friedensburg : The history of the University of Wittenberg . Niemeyer, Halle an der Saale 1917.

- Wolfgang Sommer : The position of Lutheran court preachers in the formation process of early modern statehood and society . In: Journal of Church History . Volume 106/3, 1995, pages 313-328.

- Wittenberg scholar studbook . Published by the Historisches Museum Berlin, Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle 1999, ISBN 3-932776-76-3 , page 327.

- Wolfgang Sommer: Politics, Theology and Piety in Lutheranism in the Early Modern Age… Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-525-55182-7 .

- Wolfgang Sommer: The Lutheran court preachers in Dresden: basics of their history… Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-515-08907-1 . [1]

- Christian Peters: Polykarp Leyser in Wittenberg . In: Irene Dingel and Günther Wartenberg (eds.): The Theological Faculty Wittenberg 1502 to 1602 . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-374-02019-4 .

- Fritz Roth : Complete evaluations of funeral sermons and personal documents for genealogical and cultural-historical purposes. Vol. 1, p. 28, R 55

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Letter from Polykarp Leyser to Jakob Andreae in Tübingen from March 2, 1577 from Göllersdorf. In: Adam Rechenberg (ed.): Sylloge epistolarum BD Polycarpi Lyseri… ex Mss.… Eruta et in unum volume congesta . Lanck Nachf., Leipzig 1706, pp. 237–248 ( Google Books , Google Books ).

- ^ Entries by Friedrich Leyser in: ze170380. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 17, Leipzig 1738, column 380.

- ↑ Threni Polycarpi Lyseri, in which four corpses and consolation sermons have moved together: which were given about the fatal departure of three of his children / as Lucae, Christiani, and Magdalenae, also his oath or daughter husband / Mr. Caspar Schreyers, the Elector of Saxon Widwen Chamberlain and Secret Society Secretarii / One / from Mr. D. Aegidio Hunnio, now also godly. The remaining three / from Mr. M. Conrado Blatten, Churf. Saxon court preachers. ( Digitized version )

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Martin Mirus |

Court preacher in Dresden 1594–1610 |

Paul Jenisch |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Leyser, Polycarp the Elder |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Leyser, Polycarp of |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Lutheran theologian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 18, 1552 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Winnenden |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 22, 1610 |

| Place of death | Dresden |