Usury in the country

The usury in the countryside was a sort of usury in rural areas especially to the detriment of small farmers in the second half of the 19th century. It is described here using the example of occurrence on Prussian- ruled territories. There were comparable developments throughout the German Reich . The characteristics differed only in that there were fewer smallholders in the eastern areas, as the areas there were largely cultivated by landowners with farm workers due to a different historical development .

Usury occurred in various forms, but what they all had in common was that business people exploited their economic and - due to their better education - intellectual superiority. Out of ignorance and inexperience, a large number of small farms became insolvent and even foreclosed . The usury law passed in 1880 and its amended version in 1893 came too late to have been able to mitigate the consequences of usury.

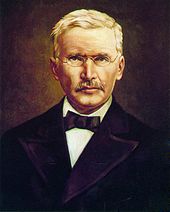

For Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen , the effects of usury were the most important reason for founding the socio-reform cooperative Raiffeisen movement named after him .

The terms rural usury or usury in the country are used, although it is only about usury at the expense of farmers. Since almost all residents of rural areas, including teachers, priests and doctors, were still doing at least a small amount of farming full-time or part-time towards the end of the 19th century, there was no distinction between rural and agricultural. In the literature on Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen, the term cattle usury is mostly used to describe.

Initial situation and causes

One of the main reasons for usury in the country was the consequences of the liberation of the peasants . They had freed the previously serf peasants from their absolute dependence on the feudal lords and granted them many individual freedoms, including ownership of the farmed land. On the other hand, the feudal lords were no longer obliged to look after the subjects in times of need. The now free farmers also had to compensate the previous landlords either with land cessions or with transfer fees. While in the eastern part of Prussia the smallholders mostly had to give up around a third of their cultivated area, which weakened them economically in the face of the landlords, transfer fees were common in the western and southern parts of the country (mostly in the amount of 2000 to 4000 Talers ).

Another burden on many small-scale farms resulted from inheritance or the transfer of farms as part of anticipated inheritance . The Anerbenrecht was handled so after the abolition of serfdom in the Prussian state that the compensation-stepping heirs was made law after the actual sale value of the land. Lorenz von Stein wrote about this as early as 1880 that the former rear occupants therefore became "Laffen des Capitals". Overall, the burdens on the farmers had by no means diminished, but at best shifted, so that many of them fell into the hands of loan usurers through their new dependence on money.

Especially for the small farmers with the smallest amount of land, the situation after the liberation of the farmers often turned out to be an existential emergency that could not be mastered. Thereafter, the landlords were no longer obliged to give them the consideration for their serfdom, which had previously been laid down as payments in cash and in kind. Likewise, their obligation to provide needy, sick or old farmers with seeds, wood, food and other goods to cover the most urgent needs was dropped. The smallholders had previously obtained their fodder mostly on the commons . As part of the separation, this was distributed proportionally to the rest of the area, which deprived them of any opportunity to keep their cow or goat.

With the abolition of the manorial obligation to help needy subjects, years with bad harvests, illness or death of the farmer, damaging events such as a fire on the farm or an epidemic of livestock immediately became an existential problem for those affected. There was no insurance or state loss prevention and it was also the mentality of the time to view such individual disasters as “God's punishment” and to accept one's fate instead of taking precautions. The 19th century was characterized by several years of bad harvests, subsequent famines (e.g. famine year 1816 ) and outbreaks of disease and epidemics in humans and animals that could not be combated at that time. Several waves of emigration were the result. Those who stayed at home, on the other hand, were easy victims for usurers at a time when there were no comparable loan offers.

Almost all companies were faced with the challenge of mastering the transition from subsistence farming to a company producing for the market economy. At the beginning of the 19th century, the rural population often did not need any money. Both the local craftsmen and the taxes could be paid with self-produced natural produce. Due to the industrialization in the cities, there was an increased demand for agricultural goods. In order to satisfy them, however, the companies had to increase their profitability . There was a change from three-field to crop rotation on the usable areas . Production could be increased with previously unknown products such as high-performance seeds and plants, high-performance breeding animals, fertilizers and, from the middle of the 19th century, machines with which crops can be tilled and harvested faster and therefore less dependent on the weather. Thanks to the population development, there was more than enough workforce. The farmers were unable to assess the profitability of individual investments. Most had to rely on the promises of the sellers - and they were also the only available lenders and, in this capacity, often self-serving usurers.

In the entire 19th century, smallholders had to familiarize themselves with a market for the first time. Especially in areas remote from metropolitan areas, middlemen took over both the purchase of products and the sale of operating resources. It was common for a trader to become the sole “court trader” of a company and entire villages. If there were several traders, they usually agreed with each other and granted each other territorial protection. Many traders took advantage of this quasi monopoly position . Since the only banks were often more than a day's walk away in larger cities and were not geared to the needs of rural customers, the alternative of a bank loan instead of supplier credit was virtually out of the question. Even if a farmer had been able to provide the required securities, which was seldom the case, he would have had to expose himself as a debtor through the required declaration by local authorities about his economic and personal circumstances. The rural trade based on mutual trust and traders succeeded mostly to become the confidant of the farmer, especially after the emancipation of individual members of the village community rivals (to face the most beautiful yard, the largest social reputation) had become that no longer worried about the common good.

However, none of the above-mentioned reasons weigh as heavily as the inexperience and carelessness of the population. Small farmers often attended elementary school for only a few years . School attendance was irregular for many because the writing and arithmetic lessons were paid and they had to help on the farm as a child. The teachers were poorly trained. Religious instruction and education to be loyal subjects were more important than learning to write and mathematics. The standardization of "natural" measures (cubit, bushel, foot, etc.) to the modern abstract decimal measures already overwhelmed most of them. They were not able to calculate interest or even compound interest. It was also in keeping with the reality of their lives up to now to take care of the best possible production and to leave commercial activities to those who thought they could do it better. Thus, as inexperienced, backward-thinking and poorly educated market participants, they were exposed to usury without protection. Very few of them afforded private luxury, although their standard of living approached that of the rest of the population at best. According to today's understanding, however, there have been many cases in which farmers themselves contributed to their economic ruin, for example by paying too high prices, especially when buying land, driven by the hope that a current high price would continue.

Forms and extent of the usury in the country

There is relatively detailed information about the various types of usury in the country from a study by the Verein für Socialpolitik from 1886. It covered the entire German Empire and confirmed “devastating damage” by usury in all parts of the country. The Rhine Province , Baden and the realm of Alsace-Lorraine were particularly hard hit . However, the study remains rather vague about the true scope and does not contain any statistical evidence.

It can be assumed that excessive usury was the exception. The business relationship based on mutual trust between farmers and their "court merchants", which existed in many areas until the 20th century, seems to speak for it. On the other hand, like all other ways of obtaining personal advantages within the framework of existing legal requirements, usury is a deeply human trait, with individual extreme cases presumably having a particular influence on the traditional presentation.

However, it should be taken into account that for most farmers almost all transactions were carried out through just one (intermediate) dealer and that the various forms of usury and fraud described below could certainly be used by a single dealer in combination with his business partner. Even if someone was only moderately overreaching in individual cases, in the course of time he could make the farmer dependent on himself until he could no longer buy or sell anything without his consent. At the time, some dealers were also referred to as the "bird of the dead", "peasant flayer" or "cold fire". Karl Theodor von Eheberg described the combination of different types of usury in the country in 1880 as something that "far exceeds anything that has existed before in intensity, only sucks the poorest of the poor (cottagers and small farmers) and is used by the richest, to restore the abolished slavery in the most heinous form. "

Usury

Hugo Thiel , who had worked out the study, called the "money usury" in a summary of the results in 1888 as "the form under which the usurious business usually begins and under which it is continued". The usury law passed in 1880 had n't changed anything about this, as it left the creditors too many possibilities of circumvention and also because judges lacked the necessary economic expertise to properly implement vague formulations of the law.

Since only excessive interest rates were forbidden in the law , usurers in some cases completely waived interest rates or set low interest rates and took advantage of the borrowers with high commissions. In the promissory note or bill of exchange , a higher amount was then indicated to be subject to interest and also to be repaid than was paid out. The study reports on a trader from Trier who paid a farmer 100 thalers on December 10, 1878, and had himself signed a promissory note for 150 thalers due on January 1, 1879.

In the areas on the left bank of the Rhine, where the Civil Code continued to apply , buying for repurchase was an often used means of usury. In order to obtain a loan, farmers were forced to sell the usurer a piece of land at half price, which he would only get back at full price if he paid all the installments on time. So even if he succeeded, he would pay and earn double the loan amount.

Borrowers were also often defrauded by the practice of setting small absolute interest rates with short repayment periods. So it was possible that 5 or 10 pfennigs weekly interest became relative interest rates of 60, 80 or more percent per year. The legal prohibition on excessive deferment fees has often been circumvented by deliberately setting the repayment on a date before the harvest. Since the creditors were then unable to pay, they were "generously" granted a short extension of the deadline for natural produce (e.g. potatoes, ham or chicken), the value of which was usually well above that of a reasonable deferral fee.

An often chosen means was to agree a due date in the promissory note "on request" and at the same time to verbally affirm that it would only be used in consultation with the debtor. It was not unusual then to change the promissory note into a bill of exchange and to prolong the latter until the farmer, who often did not keep track of this, was in debt for the value of his property. After that, the debts were entered as a mortgage and the farm was foreclosed.

Often people simply cheated on accounts. The distinction between usury still covered by the law and downright fraud was fluid. Since many debtors could not read and write correctly, as described above, it was easy for fraudulent moneylenders to double interest, incorrectly add sums, or issue incorrect receipts. An example specifically described in the study describes a farmer from Thuringia who had cashed a bill on the due date. The moneylender kept him on the grounds that his wife did not need to know about the debt and promised to burn him. Later he sued the same for repayment, where the court agreed with him due to the strict bill of exchange law. Especially in innkeeping after drinking alcohol, which was not unusual at the time, there were always fraudsters who managed to obtain blank signatures under a pretext or with threats, with which they drew up contracts, which then meant the ruin of the signature.

Usury

For many small farmers, a single cow was the livelihood, and even for the owner of several cows, each one was essential to his or her existence. Livestock dealers could consciously take advantage of the plight of a farmer who needed a new cow.

Traditionally, all livestock trade was only carried out through intermediaries and intermediaries. These were even interposed in transactions between direct neighbors, because of mutual fear of being taken advantage of. In contrast to the chronically financially tight farmers, traders were able to pre-finance the money for a while. Some middlemen took advantage of their monopoly position to take far excessive commissions and agency fees, some of which were as high as the value of the animal. Even if a farmer tried to organize the sale himself, the dealers often succeeded in sending potential buyers on their behalf who offered a price well below value and at the same time found new defects in the animal until he could do the business himself . The bogus buyers then received a rather small share of the profit.

Another form of usury was selling on Borg . The buyer received the animal from the dealer with no or only a small down payment. If payment in installments was agreed, in the event of default in payment he took the animal back with reference to the agreed retention of title or exchanged it for a less valuable one. As a result, it happened to many farmers that they fed a calf or young cattle until the first calving was imminent, which was then taken from them in order to exchange it for a young cattle. Or that they had to pimp a skinny, milked cow and that it was exchanged for them as soon as it was in good condition again. Not only did they not have any income, but at the same time had to incur ever greater debts with the dealer in the increasingly confusing business relationship consisting of promissory notes, loan agreements, commissions and bills of animals.

This system was even more pronounced in cattle lending . In contrast to the Viehborg, the farmer did not become the owner of the animal, but borrowed it from the dealer for a previously agreed interest rate. The trader retained ownership of the offspring of the animals, so that calves, foals or lambs had to be raised by the borrower free of charge until they could be sold. The dealer had already secured himself in the contract that he could exchange the animals. Even contracts in which the farmer was paid a small amount of feed money were to the detriment of the farmer, as he was always forced to feed an inferior animal, which, as soon as it yielded, was exchanged for another animal. Since the value of the animals was estimated at the beginning and the end by the lender, a farmer could quickly find himself in debt to fraudulent dealers.

Another popular means of usury was the cattle-sharing agreement for the sharing of benefits . The trader put a milked cow in the stable for the farmer before calving. After calving, he sold the cow, whereby he himself, as an appraiser, set the initial and sales price in such a way that the farmer received almost nothing from half of the surplus and had the farmer raise the calf to the finished cow or the finished bull then to sell it, whereby the farmer only received half of the proceeds. With the contractual arrangements possible in some variants, a dealer could achieve a return on capital of 100% and more, while the participating farmer, compared to having paid the original purchase price in cash, in three years through this business model the equivalent of a cow at the time of hers lost the highest value.

The poorer the farmers in an area, the more widespread the cattle usury was. It was the form of usury in which the mostly involuntary distress in connection with the lack of commercial knowledge of the contracted partner was most ruthlessly exploited.

Land usury

For a long time, the size of a farm and thus the social reputation of the owner was measured according to how much area he managed and how many animals he was able to look after. The lease of land was unusual in the 19th century. In the middle of this century there was a real “hunger for land”, also due to the fact that many day laborers and workers could and wanted to afford property. Some traders knew how to ruthlessly exploit this.

With skillful persuasion, they succeeded in selling properties far beyond their value and even omitting the entry in the land register when contracts were often concluded in private. If the farmer was then unable to make the agreed regular payments, they were often only deferred on the condition that he took over another piece of land well above its value. With the appropriate promissory notes it was then possible for the dealer to forcibly auction the farm and usually take it over himself. Not infrequently he started the "business" with the next farmer from scratch.

The most common form of land usury was what was known at the time as “butchery”, “butchery” or “lump purchase”. A dealer bought larger plots of land in order to then sell them on in parcels for two to three times the original purchase price. In the study mentioned at the beginning, a trader from the Merzig district is named as an example , who in 1874 bought a 300- acre estate for 40,000 thalers, payable in ten annual installments. He parceled out the property and auctioned 120 acres of it to various bidders for 38,000 thalers, payable in ten annual installments plus 5% interest and 8½% buyer's premium. He himself kept 120 acres of farmland and 60 acres of forest. The study wrote a 120 to 140% gain in no time. Once a trader was in business with a farmer, he could direct the further conditions at his own discretion if he defaulted on payment. In order to escape the foreclosure auction, the debtors were almost always willing to exchange their good properties or even entire businesses for inferior, run-down businesses, so that after a few years, former owners of previously healthy businesses had to live on the only rudimentary community poor relief available. Were also affected thereby also Altenteiler and softening heirs whose sole supply came from the operation.

August von Miaskowski described the butchering of goods in 1884 as widespread throughout Prussia and all German countries, especially around larger cities. Traders, investors as “silent partners”, clerks and notaries would work together in harmony, always on the verge of lawlessness. However, this merger would make them almost unassailable. Their business got better and better the longer they worked in one place, as the impoverished former landowners, after several farms were demolished, more and more desperately wanted a little piece of their own land again on almost every condition.

The sale of the land was often organized as an auction at the local inn. A lot of alcohol was served free of charge hours beforehand. Women who came to the inn were provided with coffee and biscuits so that they should not prevent the men from drinking. In the then tipsy atmosphere, it was usually quite easy for the auctioneer to disinhibit the bidders to such an extent that they submitted bids well above their actual value and also well above their own financial means through skillful persuasion, heating up the mood and small additions to luxury goods. In order to increase the attraction of the procedure, beer and brandy were sometimes taken from parcel to parcel - where the unique opportunity was then touted anew.

Usury

Usury in trading goods took all conceivable forms. Buying below and selling, including useless goods, well above the retail price, were his forms. An initially only small debt relationship to a trader caused by this often led in the long term to economic ruin. For small businesses in particular, there was often no alternative to their “court merchant”, who was sometimes the only one in the village. The latter was then able to dictate its price. It is also reported that farmers who urgently needed money before the harvest were bought the entire harvest with a preliminary contract, although in the case of an Alsatian hop grower it is said that they were only given 20% of the later price.

Pure fraudulent transactions in which fertilizers were incorrectly declared, profit margins of over 1,000% were added, incorrect weight and ingredient information were given, etc. were widespread. Just as with usury, this was only possible because the traders were economically superior to the farmers and, thanks to their better education, also intellectually.

Traveling traders, who at that time for the first time went through the landscape with colonial goods , fabrics, jewelry and all sorts of trinkets and brought the "scent of the wide world" for the first time to the most remote village, often chatted unnecessary things to people at a price they could not afford , on. Liquor dealers in particular, but also others, liked to leave goods with potential customers for safekeeping. If they could not resist and used or consumed them, they would take as much in kind as they could find as a reward. In terms of value, however, these always exceeded the delivered goods by a lot.

Attempts at problem solving

From the legislature

The obvious problems led to the usury law passed in 1880 being tightened and made more precise in 1893. The new version of Section 302 a of the Criminal Code should include all credit transactions. Section 302 e of the Criminal Code also made usury a criminal offense in “legal transactions of any kind”. The legislature reacted to the study by the Verein für Socialpolitik and tried to protect the weaker business partner. However, since the law explicitly only applied to commercial and habitual cases, many offenders remained unpunished in everyday legal practice.

It was tried with further laws to counter particularly negative effects within the hitherto unregulated contractual system between farmers and traders. Also from 1893 onwards, every debtor had to be presented with a written invoice for his entire debts at least once a year in order to avoid a foreclosure auction as a last resort. The serving of alcoholic beverages at public auctions was also banned. Another law created the conditions under which the state could prohibit loan brokers, livestock and real estate dealers from continuing to work if there were facts that indicated unreliability.

In addition to direct usury laws, the state recognized the importance of better education for the rural population and the social strengthening of the peasant class.

"We have to maintain and raise the earning classes - especially the farmers - economically, financially, socially - that is the only correct social policy ..."

External signs of this policy were the return to farm rules in the 1870s, which eliminated the high severance payments for heirs who moved away and the fragmentation of rural property was halted, as well as the pension property legislation, with which newly settled farmers were granted state aid, making them more independent of the "Goods butchers" were. The protective tariff policy , introduced to protect aristocratic landowners from the East Elbe, also helped smaller businesses to survive.

Overall, the government measures remained relatively ineffective and came too late. The basic evil of the dependence of the smallholders on the traders was their lack of education and the non-existent alternatives to obtaining credit. Neither loans nor education can be prescribed by the state - but within the framework of the general interest a state can provide educational facilities and also create the conditions for credit institutions. At the time, the public-law savings banks were set up purely as savings banks for low-income earners and remained too inflexible when it came to lending and interest rates that were too high for farmers to consider them as an alternative to traders.

Raiffeisen cooperatives as self-help

Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen , who was mayor of various places in the Westerwald , had founded a charitable association at his first place of employment in Weyerbusch with the Weyerbuscher Brodverein . Even there he saw usury as one of the main reasons for the plight of the residents. He realized, however, that an association that distributes alms could help alleviate the greatest misery, but in no way improve the situation of those affected in the long term.

In 1849, after moving to the larger mayor's office there, he founded the Flammersfeld Aid Association in Flammersfeld . He convinced wealthy residents to vouch for their entire fortune . With this security, loans could be taken out with which indigent small farmers could hire cows at fair credit terms and at several annual installments with moderate interest rates. As long as Raiffeisen ran the business of the association, it worked successfully and generated surpluses. After he was transferred to Heddesdorf , business activities fell asleep.

The Heddesdorf charity he founded there was supposed to both provide loans to buy cattle and help the socially disadvantaged. FW Raiffeisen believes it is important to help disadvantaged children, the unemployed and released prisoners. Since the other members of the association did not want to support this, the charity was dissolved in 1864 and the Heddesdorfer Loan Fund Association was founded . In this, for the first time, poor borrowers could also become members, who thus turned from alms recipients into full participants in business operations. The initial orientation to that of Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch founded Vorschußvereine was soon abandoned, since they paid the special needs of rural borrowers after long repayment terms and the inability of borrowers who established there entry fees and shares not taken into account. In 1869, based on the Anhauser Dalehnkassen-Verein, the association was divided into four smaller associations, each of which should look after the area of a parish . The new associations also organized the purchase and sale of operating resources and harvest products for the first time, making them the first commodity cooperatives. The later founding of regional and supraregional associations only served to consolidate and expand the rural cooperative system, which differed in essential points from the Schultze-Delitsch system for commercial cooperatives.

The aim pursued by Raiffeisen of alleviating the plight of the rural population, for which he blamed their unsatisfied need for credit on fair terms as the main reason, could be achieved with the Raiffeisen loan offices and goods cooperatives. The usurers, who were referred to by Raiffeisen as “greedy predators” and “unconscionable greedy bloodsuckers”, lost their monopoly, which had often existed before, in areas with a cooperative and had to face competition with it.

literature

- Writings of the Verein für Socialpolitik

- Volume 22: Rural conditions in Germany. Leipzig 1883.

- Volume 35: Usury in the Country. Leipzig 1887.

- Volume 73 and 74: Personal credit for small rural property. Leipzig 1896.

- Martin Fassbender : Rescuing the peasant class from the hands of usury. Munster 1886.

- Lorenz von Stein : Usury and its rights. Vienna 1880.

- Ernst Barre: The rural usury. Berlin 1890.

- Hermann Blodig : Usury and its legislation worked historically and dogmatically. Vienna 1892.

- Adolf Wuttig : FW Raiffeisen and the rural loan associations named after him. Neuwied 1921.

- Adolf Scherer: From the beginnings of the Hessian Raiffeisenism. Kassel 1941.

- Katja Bauer: The Raiffeisen Cooperatives' contribution to overcoming usury. (= Cooperation and cooperative contributions from the Westphalian Wilhelms University of Münster. Volume 31). Dissertation. Münster 1993, ISBN 3-7923-0660-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, ISBN 3-7923-0660-3 , pp. 71-73.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 74/75.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 76/77.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 74/75.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 78-80.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 80/81 and 86-90

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 91-93.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 93-95.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 45.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 45/46.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 46 and p. 72.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 46.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 47.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 47.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 46/47.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 48-50.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 51.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 51/52.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 53.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 54/55.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 54-57.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 57.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 58/59.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 59/60

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 60/61.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 60.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 62.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 61-63.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 66.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 66/67.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 96/97.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 98.

- ↑ quoted from Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 99.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, p. 99.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 82/83 and 100.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 102-104.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 104/105.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 105/106.

- ↑ Katja Bauer: The contribution of the Raiffeisen cooperatives to overcoming usury. 1993, pp. 108-111.