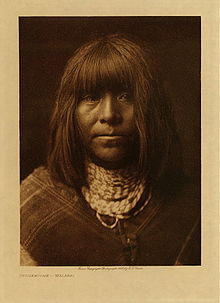

Walapai

The Hualapai or Walapai are an Indian people in the southwest of the USA and, linguistically, culturally and geographically, together with the relatives Havasupai and Yavapai, belong to the group of the Highland Yuma (Upland Yuma) or Northern Pai in the northwest, southwest and western central Arizona .

The Northern Pai originally lived on the Upper Colorado River north of the mighty and warlike Quechan (Yuma) in Arizona and moved eastward into the canyon lands and canyons of the Colorado Plateau, including the Grand Canyon , long before the first conquistadors set foot in what is now the southwestern United States . According to traditional tradition, two separate tribal groups emerged from this original group due to internal disputes, which were now also hostile to each other: the Yavapai, who moved further into southwest and south-central Arizona, and the Hualapai (Walapai), who stayed in the northeast and north.

It was only with the establishment of the Havasupai Reserve in the 1880s for the Havasooa Pa'a / Hav'su Ba: local group of the Hualapai, who had previously withdrawn deeper and deeper into the canyons for protection, did they gradually no longer begin as Hualapai (Walapai), but to be identified as a separate tribe .

Names

The Hualapai (Walapai) and Havasupai are often called northeastern Pai to distinguish them from the southern Yavapai ; Since the forced settlement in two reservations - the Hualapai Indian Reservation in the west and the Havasupai Indian Reservation in the east of the originally common tribal area - the Hualapai (Walapai) are referred to as Western Pai and the Havasupai as Eastern Pai .

Like many indigenous peoples, they referred to themselves as Pai, Paya, Paia, Pa'a, Báy or Ba: ("the people") , depending on the dialect .

The tribal name used today as Hualapai (Walapai) is an English adoption of the name of a band of the Hualapai (Walapai), which is Hwa: lbáy / Hual'la-pai / Howa'la-pai (derived from Hwa: l - " Ponderosa -Kiefer "and Báy -" people ", i.e." people of the high Ponderosa pine ").

The designation as Havasupai is also an alienation of the autonym of the largest local group of the Hualapai (Walapai), who called themselves Havsuwʼ Baaja or Havasu Baja ("people of blue-green water") - they were called by other Hualapai due to the different dialect Havasooa Pa'a / Hav'su Ba: ' denotes. Other spellings commonly used in historical reports: Ahabasugapa, Yavasupai or Supai

The Hopi referred to both the Hualapai (including the Havasupai) and the Yavapai as Co'on / Coconino ("Wood Killers"), the name referring to the way in which they cut the branches off the trees with axes. The hostile Navajo adopted these names and referred to the Hualapai (Walapai) as Waalibéí dinéʼiʼ and the Havasupai as Góóhníinii ; however, the Navajo name for the Havasupai could have the same etymology as Koun'Nde / Go'hn ("wild, rough people") of the Western Apache for the Yavapai and their Tonto-Apache relatives.

The hostile Yavapai referred to them as Matávĕkĕ-Paya / Täbkĕpáya ("people in the north", according to Corbusier) or as Páxuádo ameti ("people far downstream", according to Gatchet ), while the Hualapai (Walapai) and Ji Havasupai called the Yavapai 'wha ("The Enemy") - the largest and southernmost large group (sub-tribe) was also known as the Yavapai Fighters .

The O'Odham (Upper Pima) called all Northern Pai as well as the Apache and Opata simply Ohp or O'Ob ("Enemies").

Because of their lifestyle, which hardly differs from the southern and eastern Yavapai and Tonto Apache , the Spaniards, Mexicans and Americans called the Hualapai (Walapai) and Havasuapai just like the Ɖo: lkabaya / Tolkepaya ("Western Yavapai") Yuma-Apache or Apache- Yuma , because in northern Mexico and in the southwest of the USA the word Apache was often used to denote "hostile, warlike, predatory Indians", without linguistic, ethnic and cultural differentiation (also Mohave (Mojhave) and even Comanche were previously referred to as Apache ). In historical specialist literature and in adventure novels (as in Karl May : Nijjorras Apatschen) these misleading terms are still used; However, the origin of the now commonly used tribal name "Apache" for all tribes and groups of the Southern Athapasques - except for the Navajo - is uncertain and controversial.

language

Their language is one of two dialect variants of Havasupai-Hualapai (highland Yuma) and, together with the closely related Yavapai of the Yavapai, belongs to the highland Yuma (northern Pai) branch of the Pai or northern Yuma subgroup of the so-called actual. Yuma languages of the Cochimí-Yuma language family , which is often counted among the Hoka languages . The second dialect variant, which differs only minimally, is spoken by the Havasupai (Kendall 1983: 5), but both dialect variants are given differently in writing. The speakers of Hualapai and Havasupai also regard their dialects as independent languages, despite the great similarities and mutual intelligibility. However, there are major deviations between Havasupai-Hualapai and the four dialect groups of Yavapai, which also belong to the highland Yuma.

Today, out of around 2,300 Hualapai (Walapai), only around 1,000 tribesmen (2000 A. Yamamoto) speak their mother tongue. Of the 650 (2010) Havasupai today, 530 still speak their language. and thus Havasupai is often referred to as the only Native American language in the United States that is 100% spoken (or understood) by all tribal members.

residential area

The land of the Walapai was bounded in the west and north by the Colorado River and reached in the south almost to the Bill Williams River and Santa Maria River , in the north it encompassed southern parts of the Grand Canyon , in the west the Black Mountains and the - for all Yuma -Groups spiritually important - Spirit Mountain near Laughlin and in the east to today's Seligman (in Walapai: Thavgyalyal) and the Coconino Plateau . Coconino ("Wood Killers") is the Hopi name for both Walapai and Yavapai and refers to the way in which they cut the branches from the trees with axes. In addition to the Colorado River, the Big Sandy River was important to the Walapai. Their tribal area consisted mostly of hilly terrain, partly covered with grass or forests, rugged mesas , and deep gorges such as the Meriwhitica Canyon.

In the west, on both sides of the Colorado and along the mouth of the Bill Williams River, lived the mighty Mohave and in the southwest along the lower Colorado their allies, the warlike Quechan - but mostly these tribes were friendly. The enemy Yavapai and their allies, the Tonto Apache , had their residential areas in the south and east. The tribal area of the related and allied Havasupai (at that time only the most northeastern, most isolated and at the same time largest Walapai local group, which belonged to the sub-tribe of the Plateau People) bordered directly to that of the Walapai in the northeast, further to the east the trading partners of the Hopi had their tribal area. The southern Paiute lived in the north and the Diné in the northeast .

history

The Walapai may have been discovered by Hernando de Alarcón in 1540 . The contact with the Spaniards was limited to a brief visit from Marcos Farfan de los Gordos in 1598 and from Father Francisco Garcés in 1776, so that the problems with the whites only began with the arrival of the Americans in 1852.

Relations with the Americans were initially peaceful, but unrest broke out around 1865 when gold prospectors and ranchers illegally appropriated the Walapai's springs and watering holes. In April 1865, drunken settlers killed the Walapai chief Anasa and the Indians attacked travelers en route from Prescott , Arizona, to the Colorado river crossings. The Hualapai sent messengers to the Havasupai and even to the Yavapai and Tonto Apache to secure their help in their fight against the US Army and American prospectors and settlers. In total, there were about 250 Hualapai warriors, and an unknown number of Yavapai and Tonto-Apache allies, who fought hundreds of United States Army troops and militias. During these battles, the members of the Ha Emete Pa'a / Ha'emede: Ba: ' ("Cerbat Mountains Band") of the Middle Mountain People emerged as militant leaders, as their tribal areas in the Cerbat and Black Mountains were particularly hard hit by the mining boom were.

The Indian fighters used the so-called "hit-and-run" tactics of guerrilla warfare . H. Raids, ambushes, and attacks on US Army supply lines, as well as targeted, "needle-stick" military action designed to wear down Americans. Here they benefited from their traditional organization in independent local groups and gangs, as these formed small, independently operating combat units, which were characterized by high mobility and flexibility. In addition, they knew every hiding place and water hole or a possible place for an ambush in their country and mostly operated out of the mountains, which formed an optimal retreat area, into which they immediately retreated after attacks. This enabled the warriors to evade the militarily superior enemy. Their success depended on whether they managed to keep the decision about where, at what time and under what conditions the military confrontation with the US Army took place and the US Army out of their residential area and the settlements with their wives and children keep away.

The most important chiefs - called Tokoomhet or Tokumhet by the Walapai - during this time were: Wauba Yuba ( Wauba Yuma , leading chief of the "Yavapai Fighters"), Sherum ( Shrum or Cherum of the Ha Emete Pa'a , leading chief of the " Middle Mountain People ") and Hitchi Hitchi ( Hitch Hitchi , leading chief of the" Plateau People "), and because of the fighting, Susquatama ( Sudjikwo'dime , better known by his nickname Hualapai Charley , became an important war chief of the" Middle Mountain " People ") known. The Beale Springs Peace Agreement followed , but it only lasted nine months. After the murder of Chief Wauba Yuba in 1866 and the capture of five other sub-chiefs while negotiating with General Gregg, further unrest broke out, culminating in raids on gold digger camps and white settlers.

The US Army now adapted to the fighting style of their Indian opponents; with the support of Mohave (Mojave) - Scouts the US Cavalry led now from Fort Mojave their own guerrilla war against the Hualapai (which the existing enmity between Mohave and Hualapai only deepened): small mobile units now held in autumn and winter attacks on the rancherias of the Walapai, the Army attacks concentrated on the Cerbat, Hualapai, Aquarius and Peacock Mountains as well as on the Big Sandy Valley. The soldiers destroyed 19 rancherias along the Big Sandy River alone - including large villages with adjacent fields. Most settlements, however, consisted of 6 to 8 Wickiups and thus a population of 25 to 60 people (US Senate 1936: 70). With the help of local Mohave, Yavapai and Apache scouts, the US Army moved deeper and deeper into the hiding places of the bands, so that more and more often they had to flee from advancing army units or the enemy scouts (together with women and children). The abandoned settlements, cultivated fields, discovered food depots and winter supplies left behind - consisting of game , roasted / baked flower buds or leaves of agaves , root and grass seeds and dried beans or flour from the mesquite tree - were systematically burned and destroyed by the US Army to starve the Indians (US Senate 1936: 46,59,90). If the army managed to surprise the settlements so that the residents could not flee in time, the warriors were usually killed (and with them their horses to destroy mobility) and the women and children kidnapped in captivity. During these campaigns, there were several small skirmishes and the soldiers built the forts Camp Date Creek (1867 on Date Creek along the road between Prescott and La Paz) and Camp Hualapai (1869 along Walnut Creek to the north as bases for further advances into the Hualapai tribal area from Prescott, southeast of Aztec Pass). The Walapai warriors were feared and desperately resisted, but could not withstand the overwhelming odds. The fighting peaked in January 1868 as Captain SBM Young, later by Lt. Supported Johnathan D. Stevenson, who surprised and attacked Chief Sherum's rancheria with more than 100 warriors. Known as the "Battle of Cherum Peak", the clashes lasted all day, Stevenson fell in the first volley, the Walapai managed to escape - but they had lost 21 warriors and many were wounded. This battle broke the militant resistance of most of the Walapai.

The allied bands of the Walapai, Yavapai and Apache were always on the run due to this changed tactic of the US Army , because in contrast to the Americans with their standing army , the fighting Indians were not professional soldiers or scouts who knew their families were safe as well as a regular supply of troops. During the Hualapai War (1865-1870) and the Yavapai Wars (1861-1875), the Indians were constantly attacking their war troops and their settlements (with their women, children and old people hidden there) by the US Army and theirs Allied Indian scouts (mostly Mohave, northeastern Pai and western Apache, as well as Maricopa, Upper Pima and Navajo) exposed. The soldiers, settlers, militias and scouts, who were now advancing further and further into their settlement area and the last bastions, made it more and more difficult for the bands to organize enough food supplies and clothing for the harsh winter - fields could not be tilled or harvested, it was gathering and hunting also only possible with an increased risk and there was simply no time to manufacture the necessary clothing and to set up food depots for the winter. Already weakened by the ongoing fighting and flight as well as the outbreak of hunger in winter, about a third of the Hualapai died as a result of the diseases that now emerged.

Only in December 1868, the Hualapai gave under the leadership of the chief Leve Leve ( Levi Levi or Levy-Levy of the Amat wha-la Pa'a or Mad hwa: la Ba: the Yavapai Fighters ), a half-brother of the chiefs Sherum and Hualapai Charley , on when they were afflicted by serious illnesses such as whooping cough and dysentery (dysentery). However, the leading chief during the war of the "Yavapai Fighters" was Sookwanya (son of Wauba Yuma) and not Leve Leve (who was chosen by the Americans as the "peace chief" of all Hualapai during the reservation period), and Tokespeta followed as the leading chief of the "Plateau" People "(but could never reach the prestige and position of Hitchi Hitchi). The last warriors, led by the chief Sherum , famous for his tenacity , did not surrender until 1870. After the Walapai surrendered, a US general said: "He would rather fight five Apache than the Hualapai". This saying was a great honor for them, because after all, the Apache were considered the best guerrilla fighters in the world.

To avoid further bloodshed, the now defeated Hualapai (with the exception of the later Havasupai) first had to move to a reservation near Camp Beale's Spring, three years later they were forced to move to the Colorado River Indian reservation on the Colorado River , which is mostly inhabited by hostile Mohave Relocate La Paz; many of them fell ill in the heat of the unfamiliar lowlands and died. However, some were able to settle on a reservation near Camp Date Creek along Date Creek and the road between Prescott and La Paz - but this was closed in 1874. The conditions on the respective reservations led to famine and disease, so that many desperate Hualapai fled back to their original tribal territory in 1875. However, in recent years, many whites had appropriated their land in their absence and the Hualapai (Walapai) suffered great hardship, so they were forced to accept government food in order to survive. In 1882 a 900,000 acre reservation was made for them, but in an area the Americans considered unsuitable for their purposes. It is estimated that about a third of the Hualapai population perished between 1865 and 1870 during the Hualapai War, the forced resettlements in reservations and due to diseases and famine .

Because the Walapai were not belligerent and therefore harmless, the majority of the Americans regarded them as an unbearable plague; an 1887 editorial in a newspaper, the Mojave County Miner , said that Indian rations should be mixed with a sufficient amount of arsenic to solve the problem.

Way of life and culture

The Walapai were a small tribe whose total population did not exceed a thousand. Their tiny settlements usually consisted of two or three families and were scattered on the arid plateau wherever a constant supply of water could be found. The Walapai did some farming, but mostly ate game and edible wild plants.

Though not particularly belligerent, they occasionally fought the Paiute and Apaches . Particularly bitter to the were Yavapai counting Yavapé and Tolkepaya fought. In these fights, which were particularly bitter because of the well-known common origin and language (the opposing parties could understand insults and insults in the fight), ritual cannibalism occurred in at least one case (at least on the side of the Walapai and Havasupai). Peaceful trade relations, however, existed with the Mohave , Chemehuevi , Quechan and other tribes in the area of the lower Colorado River. Here they exchanged red pigments that they extracted in Diamond Creek Canyon for mussels and crops. The mussels, in turn, together with red paint, tanned animal skins, collected desert plants - and roots, they exchanged with the Havasupai and Hopi for corn, other foods and handicrafts, while the Diné gave them the famous Navajo blankets and artistic turquoise work. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that around 1890 the Walapai were avid participants in the ghost dance , a messianic movement that began by a Paiute medicine man named Wovoka . The prescribed dances were danced for two years and it was believed that the dead would return and the hated whites would go away.

Todays situation

Today the Walapai inhabit the 4,020 km² Hualapai Indian Reservation with the main town Peach Springs , which is located about 80 km east of the city of Kingman in Arizona in the northern Arizona counties Coconino, Yavapai and Mohave. In 1883, one year after the establishment of the neighboring Havasupai Indian Reservation, the Hualapai Indian Reservation was created. The reserve is now divided around two settlements: Grand Canyon West , the tourist center, and Peach Springs, the administrative center and main town where most of the Hualapai live. Today around 1,621, of whom 1,353 are Hualapai tribesmen, live on the reservation. Of the approximately 2,300 Hualapai nationwide today, those who do not live within the reservation live near or mostly in cities in the United States.

Today's reservation is in the former territory of the Plateau People , who considered four local groups to be part of their tribal area: the Yi Kwat Pa'a / Iquad Ba: ("Peach Springs Band") the area around the main town of the same name, Peach Springs in the center of Reservation, the Ha'kasa Pa'a / Hak saha Ba: ("Pine Springs Band") the east, the He: l Ba: ("Milkweed Springs Band") the west and the Qwaq We 'Ba: ("Hackberry Band "Or" Hackberry Springs Band ") the extreme south. The other local groups of the Hualapai (including the Havasupai) lived a long way from today's reservation.

The name Peach Springs comes from the peach trees that grow near a spring. But the place has little in common with this idyllic picture. As in most other Indian reservations, the people in the Hualapai Indian Reservation also live off their barren land and suffer from high unemployment. The effects of alcohol and a lack of prospects are reflected in the shabby huts and dwellings throughout the place.

Because of the limited natural resources , most of Hualapai have to leave the reservation to earn a living from wage labor. Basket making is the only traditional Indian craft that is still practiced today. All wickerwork of the Walapai has a diagonal thread weave; Ribbons of simple geometric patterns in color are the only decoration. Nowadays, livestock is an important livelihood for the Walapai. Except in a limited area on the Hualapai Indian Reservation , most of the tribal land is unsuitable for agriculture. The tribal income is earned from tourism and timber sales.

The Walapai run the Grand Canyon West Adventure Park outside of Grand Canyon National Park . Its best-known attraction is the Grand Canyon Skywalk , a steel construction with a glass floor and walls, which allows a view straight down into a side canyon.

Socio-political organization

Ethnically, the Havasupai and Walapai (Hualapai) are one people (or tribal group), although - as a result of the arbitrary concentration of groups in reservations by the US government - today both form separate, politically independent tribes - and have developed their own identity. The Hualapai (Walapai) consisted of three major groups (or sub-tribes ) - the Middle Mountain People in the northwest, Plateau People in the east, and Yavapai Fighters in the south (McGuire; 1983). This large group divided into seven bands (Kroeber, 1935, Manners, 1974), which in turn made 13 (originally 14) local groups (English, regional bands and local groups ) were (Dobyns and Euler, 1970). These local groups were composed of several or one large family group (English extended family groups ), each of which lived in small settlements ( rancherias ). The Havasupai or Havasooa Pa'a was the most northeastern, most isolated and at the same time the largest local group of the Hualapai (Walapai), but belonged as well as the Yi Kwat Pa'a ("Peach Springs Band") and Ha'kasa Pa'a ("Pine Springs Band ”) of the Nyav-kapai band (“ Eastern People ”), which belonged to the sub-tribe of the Plateau People .

Groups of the Walapai

Plateau People or Ko'audva Kopaya ("The People Up Above") (lived in the plateau and canyon land of the eastern Hualapai Valley and the Peacock Mountains in the west northeast east of the Truxton Canyon Wash and the Grand Wash Cliffs as far as the Music Mountains, also had plantings at Metipka, a spring in Quartermaster Canyon, today's Hualapai reservation includes parts of their tribal area, comprised seven groups from west to east)

-

Mata'va-kapai ("Northern People")

- Ha Dooba Pa'a / Haduva Ba: '("Clay Springs Band", suffered heavy losses during the war, lived in the Grand Wash Cliffs and Aquarius Cliffs)

- Tanyika Ha 'Pa'a / Danyka Ba:' ("Grass Springs Band", could for the most part stay away from the fighting)

Villages (located on the edge of the Grand Wash Cliffs): Hadū'ba / Ha'a Dooba ("Clay Springs"), Hai'ya, Hathekáva-kió, Hath'ela ("spring"), Huwuskót, Kahwāga, Kwa'thekithe 'i'ta, Mati'bika, Oya'a Nisa ("spider cave"), Oya'a Kanyaja, Tanyika' / Danyka ("Grass Springs")

-

Ko'o'u-kapai ("Mesa People")

- Kwagwe 'Pa'a / Qwaq We' Ba: '("Hackberry [Springs] Band" or "Truxton Canyon Band", later merged with the "Peach Springs Band")

- He'l Pa'a / He: l Ba: '("Milkweed Springs Band", lived from Truxton Canyon to Ha'ke-takwi'va ("Peach Springs"), suffered heavy losses)

Villages (the largest settlements were near Milkweed Springs in Milkweed Canyon and Truxton Canyon): Yokamva (today: "Crozier Spring" - American district), Djiwa'ldja, Hak-tala'kava, Haktutu'deva, Hê'l ( "Milkweed Springs", used in particular for irrigation of tobacco), Katha't-nye-ha ', Muketega'de, Qwa'ga-we' / Kwagwe '("Hackberry Springs"), Sewi', Taki'otha 'wa, Wi-kanyo

-

Nyav-kapai ("Eastern People", lived in the Colorado Plateau , except for the "Peach Springs Band" the northeastern local groups - the "Pine Springs Band" and the later Havasupai - successfully kept away from the fighting and thus avoided heavy losses )

- Yi Kwat Pa'a / Iquad Ba: '(literally: "[Lower] Peach Springs Band", today's main town Peach Springs (Hàkđugwi: v) of the Hualapai reservation is in their former territory, the "Hackberry Band" was joined after heavy losses of the "Peach Springs Band")

- Ha'kasa Pa'a / Hak saha Ba: '("Pine Springs Band", also known as the "Stinking Water Band", although they had their own territory southwest and west of the Havasooa Pa'a , both bands shared the northeast of the Walapai tribal areas)

- Havasooa Pa'a / Hav'su Ba: '("Cataract Creek Canyon Band", call themselves Havasu Baja or Havsuw' Baaja - "People of the blue-green water", lived in several groups along Havasu Creek in Cataract Canyon ( today: Havasu Canyon) as well as in adjacent valleys of the Grand Canyon, today commonly known as Havasupai , due to the separation from other Hualapai by the US government they identify as a separate and independent tribe)

Villages (excluding those of the Havasupai): Agwa'da, Ha'ke-takwi'va / Haketakwtva / Hàkđugwi: v ("Peach Springs proper", literally: "a series / group of sources"), Haksa ', Hānya-djiluwa 'ya, Tha've-nalnalwi'dje, Wiwakwa'ga, Yiga't / Yi Kwat ("Lower Peach Springs")

Middle Mountain People or Witoov Mi'uka Pa'a ("Separate Mountain Range People") (lived west of the Plateau People mostly north of today's city of Kingman (called by the Mohave : Huwaalyapay Nyava ) from the Black Mountains in the southwest east across the Sacramento Valley and the north adjoining Detrital Valley to the Cerbat Mountains (in Hualapai: Ha'emede :) and White Hills and parts of the Hualapai Valley)

-

Soto'lve-kapai ("Western People")

- Wikawhata Pa'a / Wi gahwa da Ba: '("Red Rock Band", lived in the northern part of the area up to Lake Mead and the Colorado River in the north, joined the "Cerbat Mountain Band" after heavy losses)

- Ha Emete Pa'a / Ha'emede: Ba: '(literally: "White Rock Water Band", better known as the "Cerbat Mountains Band", lived in the southern part of the area, in the eponymous Cerbat Mountains north of Beale's Springs)

Villages (most of the settlements were near water sources along the eastern mountain slopes): Amadata ("Willow Beach" near Hoover Dam), Chimethi'ap, Ha'a Taba ("Whiskey Springs"), Ha-kamuê '/ Ha'a kumawe '("Beale's Springs"), Ham sipa (today: "Temple Bar", flooded by Lake Mead), Háka-tovahádja, Ha'a Kawila, Hamte' / Ha'a Emete / Ha'emede: ("White Rock Water ", a spring in the Cerbat Mountains), Ha'theweli'-kio ', Ivthi'ya-tanakwe, Kenyuā'tci, Kwatéhá, Nyi'l'ta, Quwl'-nye-há, Sava Ha'a (" Dolan Springs "), Sina Ha'a (" Buzzard Spring "), Thawinūya, Tevaha: yes (today:" Canyon Station "), Waika'i'la, Wa-nye-ha '/ Wana Ha'a, Wi'ka -tavata'va, Wi-kawea'ta, Winya'-ke-tawasa, Wiyakana'mo

Yavapai Fighters (largest group, lived in the southern area of the Walapai tribal area, were therefore the first to fight the hostile Yavapai - hence called "Ji'wha '- the enemy" - in the south - hence their name, groups of West to East, were almost wiped out during the Hualapai War by the fighting, the systematic destruction of supplies and fields by the US Army and the resulting famine and disease)

-

Hual'la-pai / Howa'la-pai / Hwa: lbáy ("people of the high Ponderosa pine")

- Amat Whala Pa'a / Ha Whala Pa'a / Mad hwa: la Ba: '(literally: “Pine Tree Mountain Band”, better known as “Hualapai Mountains Band”, lived in the Hualapai Mountains south of Beale's Springs westwards to Colorado River Valley)

Villages (concentrated near water sources and streams in the north of their area): Walnut Creek, Hake-djeka'dja, Ilwi'nya-ha ', Kahwa't, Tak-tada'pa

-

Kwe'va-kapai / Koowev Kopai ("Southern People")

- Tekiauvla Pa'a / Teki'aulva Pa'a ("Big Sandy River Band", also known as "Haksigaela Ba: '", lived within reach of always water-bearing rivers as well as along the Big Sandy River between Wikieup and Signal as well as in the adjacent mountains)

- Burro Creek Band (lived at the southern tip of the "Tekiauvla Pa'a" area, planted along streams and in the canyons and plateaus along both sides of the Burro Creek, often married neighboring Yavapai - therefore often mistaken for Yavapai by Americans, they followed suit larger Hualapai local groups and some Yavapai)

Villages: Burro Creek, Chivekaha ', Djimwā'nsevio' / Chimwava suyowo '("Little Cane Springs", literally: "He dragged a Chemehuevi through the area"), Ha-djiluwa'ya, Hapu'k / Hapuk / Ha' a pook ("[Cofer] Hot Spring"), Kwakwa ', Kwal-hwa'ta, Kwathā'wa, Magio'o' ("Francis Creek"), Tak-mi'nva / Takaminva ("Big Cane Springs")

-

Hakia'tce-pai ("Mohon Mountains People", also known as Talta'l-kuwa , lived in inaccessible mountain areas)

- Ha'a Kiacha Pa'a / Ha gi a: ja Ba: '(literally: "Fort Rock Creek Band", better known as: "Mohon Mountains Band" or "Mahone Mountain Band", "Fort Rock Creek" is the English one Name of a spring and the main settlement of the same name on Fort Rock Creek, an upper reaches of Trout Creek, lived in the Mohon Mountains )

- Whala Kijapa P'a / Hwalgijapa Ba: '("Juniper Mountains Band", lived in the Juniper Mountains )

Villages: Cottonwood Creek (also: "Cottonwood Station"), Hakeskia'l / Ha'a Kesbial ("where one brook flows into another"), Ha'a Kiacha / Hakia'ch / Hakia'tce ("Fort Rock Creek Spring ", largest settlement), Ka'nyu'tekwa ', Knight Creek, Tha'va-ka-lavala'va, Trout Creek, Willow Creek, Wi-ka-tāva, Witevikivol, Witkitana'kwa

Demographics

James Mooney estimated the Walapai at 700 members in 1680. Alfred Kroeber gives about 1000 members of the tribe for the period before 1880, while in 1889 728, 1897 only 631, 1910 501, 1923 440 and 1937 454 tribesmen were reported. Today there are again around 2,300 Walapai nationwide, of which 1,353 tribe members live within the reservation (2000 US Census).

See also

literature

- William C. Sturtevant (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC

- Alfonso Ortiz (Ed.): Southwest . Vol. 9, 1979 ISBN 0-16-004577-0 .

- Alfonso Ortiz (Ed.): Southwest . Vol. 10, 1983 ISBN 0-16-004579-7 .

- Tom Bathi: Southwestern Indian Tribes . KC Publications, Las Vegas 1995.

- Christian W. McMillen: Making Indian Law: The Hualapai Land Case and the Birth of Ethnohistory . Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn. 2007.

- Flora Gregg Iliff (1882-1959): People of the Blue Water . The University of Arizona Press, Tucson Arizona 85721, ISBN 0-8165-0925-5 .

Web links

- Intertribal Council of Arizon: Hualapai

- The Havasupai and the Hualapai

- Hualapai

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jeffrey P. Shepherd, We Are an Indian Nation: A History of the Hualapai People. University of Arizona Press (April 2010), Page 229, ISBN 978-0816529049 .

- ^ Access Genealogy - Walapai Indians

- ^ Ethnologue - Languages of the World - Havasupai-Walapai-Yavapai

- ↑ At that time no distinction was made between Yavapai and Western Apache - especially Tonto Apache. Because of their close cultural and sometimes family ties to the Tonto Apache, the name Yavapai was not common at that time, as they were viewed as Tonto Apache or Apache-Mohaves

- ^ Utley, Robert Marshall: Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803295506

- ↑ Hualapai - Sociopolitical Organization

- ↑ further variants of the name: Hualapai Charlie , Walapai Charley or Walapai Charlie

- ↑ BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ARIZONA - People of the Desert, Canyons and Pines: Prehistory of the Patayan Country in West Central Arizona - Page 38 ( Memento of the original from March 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still Not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Leve Leve is often mistaken for a chief of the Yavapai - however he was only chief of a local group of the Yavapai Fighters , the name of which refers to their constant fights against the enemy Yavapai

- ↑ Timothy Braatz: Surviving Conquest: A History of the Yavapai Peoples , University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2003, p. 50.

- ↑ Timothy Braatz: Surviving Conquest: A History of the Yavapai Peoples , University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 2003, ISBN 978-0-8032-2242-7 , pp. 50f.

- ^ At the Crossroads of Hualapai History, Memory, and American Colonization: Contesting Space and Place

- ↑ About the Hualapai Nation (PDF; 5.0 MB)

- ↑ Jeffrey P. Shepherd, We Are an Indian Nation: A History of the Hualapai People, University of Arizona Press (April 2010), pp. 22-25, ISBN 978-0816528288

- ↑ Of these original 14 Hualapai local groups, the Red Rock Band was so mixed with the other local groups and absorbed into them before the arrival of the Americans that they were no longer perceived as an independent group

- ↑ Nina Svidler, Roger Anyon: Native Americans and Archaeologists : Stepping Stones to Common Ground, page 142, Alta Mira Press; April 8, 1997, ISBN 978-0761989011

- ↑ People of the Desert, Canyons and Pines: Prehistory of the Patayan Country in West Central Arizona, P. 27 The Hualapai ( Memento of the original from September 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 10.6 MB)

- ^ John R. Swanton: The Indian Tribes of North America , ISBN 978-0-8063-1730-4 , 2003

- ↑ THE UPLAND YUMANS

- ^ Thomas E. Sheridan: Arizona: A History , 74, University of Arizona Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0816515158

- ^ Bands of Gardeners - Pai Sociopolitical Structure

- ^ Alfonso Ortiz, William C. Sturtevant: Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 10: Southwest: 010 , Govt Printing Office (October 1983), ISBN 978-0160045790

- ↑ About the Hualapai Nation (PDF; 5.0 MB)

- ↑ Jeffrey P. Shepherd, We Are an Indian Nation: A History of the Hualapai People, University of Arizona Press, April 2010, ISBN 978-0816528288 , 142

- ^ The Hualapai Tribe Website - About Hualapai