Cyprus in the Late Bronze Age

In the Late Bronze Age (approx. 1650-1050 BC) Cyprus was an important political and economic power in the eastern Mediterranean. There were important cities and their own script . The island is very likely to be the mighty Alašija in contemporary sources. It remains unclear whether Alašija referred to a single city-state on Cyprus or the entire island.

Beginning

In the Middle Bronze Age (approx. 2000–1650 BC) Cyprus was predominantly inhabited by a peasant society. There were probably little social differences. The people lived in small villages, mostly in the interior of the island. Copper ( Latin Cuprum , Greek Kypros ) was mined on the north coast . The wealth of copper gave the island its later name. There is evidence of a trade in the eastern Mediterranean that intensified at the end of the epoch. Copper from Cyprus made its way through northern Syria down the Euphrates to Babylonia .

At the beginning of the Late Bronze Age , upheavals were evident in almost all areas of Cyprus. A strong increase in population, which was accompanied by social changes, took place. Fortifications were built all over the island, indicating troubled times and military conflicts. It appears that many Middle Bronze Age villages have been violently destroyed. There were fire horizons and mass burials. Later cities appear to have been founded and international trade started. The script was adopted by other high cultures .

chronology

The Late Bronze Age in Cyprus is divided into different phases by archaeologists based on the ceramics, although no agreement has been reached on the different classifications in detail. There is the Late Bronze Age I – III, whereby phases I and III are again divided into A to B and phase II into A to C. Around 1200 (Late Bronze Age III) the island was presumably colonized by Mycenaean settlers.

The division into three phases loosely follows the division of the Minoan ( Minoan ), Mycenaean ( Helladic ) and Aegean ( Cycladic ) world, whereby instead of the term Bronze Age , Cypriot is sometimes used. The absolute chronology of the individual phases was largely based on imported goods from Egypt , the Minoan and Mycenaean regions.

| step | absolute date | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Late Bronze Age IA | 1650-1575 BC Chr. | Warlike times, numerous fortresses |

| Late Bronze Age IB | 1575-1475 BC Chr. | Development of writing, first cities |

| Late Bronze Age IIA | 1475-1400 BC Chr. | |

| Late Bronze Age IIB | 1400-1325 BC Chr. | Intensive diplomatic contacts with the Middle East |

| Late Bronze Age IIC | 1325-1200 BC Chr. | Greatest flowering period; horizons of destruction at the end of this phase |

| Late Bronze Age IIIA | 1200-1100 BC Chr. | Strong Mycenaean influence, last heyday |

| Late Bronze Age IIIB | 1100-1050 BC Chr. | Cities are abandoned |

Settlements and cities

While in the previous periods the villages on Cyprus were more likely to be found in the interior of the island, they were now preferably built near the coast, which is certainly due to the growing importance of sea trade. A multi-level settlement system can be observed. At the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, there were initially numerous heavily fortified, but not permanently inhabited structures (compare: Nitovikla Fortress ). The function of these fortresses is not always clear. It could have been refuges. However, installations for storage also indicate their economic importance. A special concentration of these fortresses can be found on the way from the copper mining areas to Enkomi . You should obviously protect the trade in this raw material. The first coastal cities emerged.

After the Late Bronze Age IA, these fortresses lost their importance. In the interior of the country there were now smaller centers for the interim storage of various goods, which probably also served as administrative centers. There were pure production facilities. This includes farm villages, potteries and places where copper was mined.

The large cities of the early Late Bronze Age probably include Enkomi, Morphou- Toumba tou Skourou , Hala Sultan Tekke and Kourion -Bamboula, although the early history of these places is still largely unclear. In the course of the Late Bronze Age, other urban centers were added, such as Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios , Alassa and Palaepaphos . In the thirteenth and twelfth centuries, many places were restructured. During this time they were given a checkerboard map.

Enkomi is the best dug city and was a planned place with streets intersecting at right angles. There was a main road running north-south and at least eight side streets going east-west from it. The city was surrounded by a city wall. The lower part of this consisted of rubble stones and the upper part was made of adobe bricks. There were numerous workshops and various sanctuaries. A palace or other public buildings have not yet been found. Building materials were rubble stones and adobe bricks. In the 13th century BC, hewn cuboids were increasingly used for public buildings (temples and city walls).

The finds from Enkomi in particular demonstrate the type of house that was common at the time. Most of the houses had a courtyard with rooms on three sides. There were bathrooms with bathtubs; the floor of these rooms usually consisted of particularly solid material. Burials took place in the settlement area.

Political structures

As it is not yet possible to read the original written documents from this period, little is known about the political organization of Cyprus. There are essentially two opinions in research. One theory assumes that the island was divided into the rulings of different city-states, on the other hand the thesis is that Cyprus was ruled by a single king. He probably resided in Alassa, although Enkomi with its rich archaeological finds is often assumed to be the capital of the island. The idea of a unified, centrally controlled state, however, encounters certain difficulties. One font was known, but it seems to have only been used sporadically and rarely in administration. There also seem to have been small local variations in the script. There are numerous seals that were obviously not used for sealing, but rather as amulets or jewelry. So there is no clear evidence of an entire island administration.

In this context it is important that a king of Alašija appears in cuneiform sources in the Middle East, Alašija being mostly equated with Cyprus. He was evidently regarded as equal with the kings of Egypt and Babylon , which is mainly expressed in the mutual addressing of brother , while less important rulers addressed the kings of the great empires as father . Alašija appears in these texts primarily as a supplier of copper, horses and wood. The large amounts of copper mentioned in the texts alone make it probable that Cyprus or a city in Cyprus is meant. In the cuneiform texts, the king of Alašija Kušme-Šuša appears as an important ruler. He was a contemporary of Niqmaddu III. by Ugarit (approx. 1225–1215 BC).

In Hittite texts, the kings of Alašija are mentioned from the end of the thirteenth century BC. Called subordinates . It is believed that there was a brief conquest of the island, although a loose vassal relationship can be assumed. Tudhalija IV. (Approx. 1240-1215 BC) boasts of having conquered Alašija and incorporated it into the Hittite Empire. Hittite finds on the island are rare even for this period.

economy

The period is characterized by a more intensive exploitation of the copper deposits. Copper was extracted for its own use, but also for export, and made the island a powerful trading center in the eastern Mediterranean. There were also large forests on the island, which made it an important supplier of timber.

Despite these important raw materials, agriculture formed the economic basis. Wheat , barley and lentils were grown, and olives and grapes are also attested for the first time . Sheep, goats and cattle were kept on animals. There are indications that agriculture was organized centrally. Corresponding storage installations were verified. In a house in Apliki, for example, 15 pithoi were found that had a capacity of 7,500 liters and were undoubtedly not intended for the needs of the home owner. In a house in Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios, a complex was excavated in which 50 two-meter high pithoi were found, which together had a volume of 50,000 liters.

Metal processing

Copper processing played an important role. The origin of copper in the eastern Mediterranean can often not be determined with certainty, but isotope analyzes indicate that a large part of the copper in circulation at the time actually came from Cyprus. At that time it was traded in the form of ox hide bars. The height of production fell in the thirteenth and twelfth centuries BC. This period coincides with the heyday of the Cypriot coastal cities. The copper mines of this time have so far not been adequately investigated, but they were mostly in the interior of the country, away from the coastal cities. Apliki was an important mining region . There were small settlements near the copper mines where the ore was smelted and then shipped on. In combination with tin , copper made the much harder bronze , although the origin of the tin is disputed. It may have come from Western Europe such as the Tin Islands , via the Aeolian Islands in the western Mediterranean or from Uzbekistan. The processing of copper into bronze took place in Cyprus mainly in the large coastal cities, whereby it was mostly a matter of further processing for our own needs.

trade

In the first half of the second millennium BC, Cyprus does not seem to have played a major role in international maritime trade. That changed significantly with the Late Bronze Age. There was now ample evidence of trade relations extending across the entire eastern Mediterranean.

The island's main export item was copper, with Ugarite apparently being the main trading partner in the Levant . A Cypriot trading colony may also have existed there.

Cypriot ceramics were found in large quantities in Egypt and the Levant, but also in Sicily and even Sardinia . It can be assumed that the ceramic itself was not the commodity, but that it served as a container for more valuable substances. Numerous ox skin copper bars were also found in Sardinia , although the island itself had larger copper deposits. Isotope analyzes showed that the copper bars mostly came from Cyprus, but analyzes of bronze figures from the Nuragic culture showed that they were made from local copper. A fragment of a copper bar discovered in Sète in the south of France turned out to be a Sardinian imitation of a Cypriot ox skin bar. Oxhide bars made of definitely or very probably Cypriot copper were otherwise found in a depot in large parts of the Mediterranean region, in today's Iraq, in the Balkans to northern Romania (Pălatca, Cluj district ), western Hungary and the north and west of Croatia and even north of the Alps in Oberwilflingen in southern Germany . Representations of ox skin bars have been known from Egypt for a long time, rock carvings were recently discovered at two sites in Sweden, on which ox skin bars are probably also shown.

During excavations, imported articles were found mainly in the form of luxury goods, including glass and faience ware from Egypt and valuable ivory carvings from the Levant. Numerous Aegean imports have also been proven on the island. Above all, Mycenaean pottery can be found in large quantities in the coastal cities in the 14th and 13th centuries. These are mostly small bottles that are believed to have once contained perfume. Mycenaean pottery rarely appears inland. It is believed that Cyprus was an important stopover in trade with the Aegean world, whose products were shipped to Anatolia and the Levant. The increased emergence of Mycenaean ceramics may have occurred with the collapse of the Minoan maritime rule around 1400 BC. To be related. In the period that followed, the Mycenaeans took over the Minoan trading network. Cyprus also seems to have benefited from the collapse of Cretan maritime rule. From 1400 BC The real heyday of the Bronze Age culture began in Cyprus. From the Late Bronze Age III, Mycenaean ceramics were also produced directly in Cyprus.

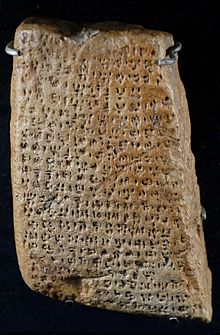

font

- see main article: Kypro-Minoan script

In 1500, the first written records came the Bronze Age Cyprus in by Arthur Evans so named Kypro-Minoan script, probably along the lines of the Minoan Linear A developed. The writing and the language are not yet understandable. There were around 100 characters, which suggests a syllabary. The preserved inscriptions are usually very short, so that there is little hope of deciphering. Although around 50 characters can be read, the language behind it is still largely incomprehensible. Clay balls, mostly from Enkomi, with a few characters that may have been used in the administration for control purposes are particularly peculiar. In addition to this writing system, known as Kypro-Minoan 1, which was used all over the island, there were two more. In Enkomi there were four clay tablets with longer texts, written down in the variant Kypro-Minoish 2. Kypro-Minoan 3 is only known from Ugarit and could have been used by Cypriots living there.

art

Various currents and influences can be identified in the art of the Late Bronze Age. The handicrafts in particular were strongly influenced by Syrian, Egyptian and Minoan-Mycenaean models (see: International Style (Bronze Age) ). As a result, it is often difficult to determine the place of production of certain luxury items, especially because these luxury items were popular objects of trade and exchange.

A faience rhyton from a grave in Kition depicts the hunt for oxen in two registers. The shape of the vessel and the style of the depictions are more Mycenaean, while the technique of depiction is more likely to find parallels in the Levant. There were many stylistically simple clay figures in sculpture. They mostly show naked female figures. Few examples are more sophisticated. Many bronze figures also usually appear rather simple. The so-called bar god from Enkomi is a standing male figure who holds a spear in his right hand and a shield in his left. The figure looks a bit awkward. The statue of a horned deity looks much more mature. She is designed in the frontal view, wears a loincloth and a helmet with protruding horns. The chest muscles are finely worked out. It is dated to the twelfth century.

Numerous gold jewelry was found in the graves of the island from this period. Here, too, the mixture of different styles can be observed. The work is technically very high, so have z. B. many pieces of granulation .

Ceramics

Cypriot ceramics from this period were found in many places in the Mediterranean. Various production centers have been identified on the island. Specialization is typical of the Late Bronze Age. While before the pottery was apparently mostly made locally, there is evidence that there were potteries, especially in the cities, in which the ceramics had been mass-produced since the Late Bronze Age IIC.

The ceramics of the late Bronze Age IA to IIB periods are characterized by the so-called base ring ceramics. It has a finely polished surface that should probably imitate metal. The vessels are decorated with straight, but also wavy relief lines. The ceramic ware is named after its (almost) always present standing ring. Two circumferential rings on the upper neck are typical. Research has suggested that the primary function of these vessels was to store opium, as they resemble poppy seed pods when turned upside down. However, more recent analyzes of base ring vessels from Cyprus and Israel did not reveal any evidence of opium.

The white slip ceramic shows geometric patterns painted yellow on a white background. The walls of the vessels are often very thin. The monochrome goods are unpainted and were already known in the Middle Bronze Age.

In the late Bronze Age IIC, the base ring and white slip ceramics were no longer used. Bowls and small base-ring vials now dominated . Less attention was paid to the painting and surface design of the ceramics. At the same time, Mycenaean goods were being produced on the island, which apparently replaced the native forms.

religion

In the absence of written sources, little can be said about the religion of that time. It has been possible to excavate various sanctuaries, especially in the cities, which differ from one another architecturally and which point to different local traditions. After all, there are certain similarities. Most of the sanctuaries had a central, open courtyard. The actual sanctuary was usually built along an east-west axis and consisted of two or three rooms. There was a hall and the holy of holies. This hall could be supported by a number of pillars. There were benches on which the cult inventory was deposited, and there were fire pits, sometimes with animal bones, indicating animal sacrifices. The cult inventory consisted mostly of ceramics, which hardly differ from the ceramics in the secular areas of the settlements.

In Greek mythology, Cyprus is the birthplace of Aphrodite . The cult of a mother goddess has been particularly visible on the island since ancient times. Even the earliest figures represent female idols that point to this cult. In the late Bronze Age, these female idols were particularly popular in tombs. They are often richly decorated and depict cultic servants, high priestesses or even the goddess herself. From 1400 BC. Syrian influence can be observed. The female figures now represent naked women with broad hips and steep chests. The pubic area is marked by a triangle. The face is like the head of a bird. A short time later, a new type of figure appears with a more human face and no longer as strongly accentuated gender characteristics. This type resembles female figures from the Mycenaean region.

Cult of the dead

A clear break from the previous epochs of the Early and Middle Bronze Age can also be seen in the dead being in the Late Bronze Age. Above all, the dead were now buried within the settlements. Most of the graves in Enkomi were found under the streets of the city or under the courtyards of residential buildings.

The typical burial of this time took place in an underground rock chamber. It consisted of an entrance shaft and the actual burial chamber, which had different shapes. It resembled the burial chambers found under the houses of Ugarit. The chambers could be oval, round, rectangular or square. A grave shaft usually led to two grave chambers, but it could also be just one or up to four chambers. There were niches and benches within the shaft and chamber. Most of the burial chambers were found robbed, but the few finds that have survived indicate that numerous additions were given to the dead. The chambers housed several dead and were in use for several generations. The discovery of numerous ceramics, especially tableware, indicates that there were funeral celebrations with meals.

Mycenaean colonization

With the beginning of the Late Bronze Age III (approx. 1200 BC), significant changes can be observed, especially in the material culture, which are associated with the arrival and conquest of the Mycenaean Greeks . Mycenaean pottery now dominated the island. New types of metal objects appeared. Many settlements have been abandoned, indicating a decrease in population, other places have apparently been destroyed and are showing layers of fire. There were only a few new places (see e.g. Pyla-Kokkinokremmos ). In Egyptian sources it is mentioned that Alašija was destroyed by the sea peoples during this time . It remains uncertain to what extent these statements can be trusted. After all, one could connect these events with horizons of destruction at various excavation sites. In any case, Cyprus - in contrast to other cultures - survived these attacks. The cities continued to be settled, prospered in the period that followed and experienced their greatest boom. This is particularly noteworthy given that at the same time many Middle Eastern states were in decline.

A particularly large number of urban sanctuaries were built during this period. The rectangular construction dominated the architecture. The cities had walls based on the Mycenaean model. They were built on two sides of gigantic unworked stones, with a superstructure made of adobe bricks. Despite these changes, in the period between 1200 and 1100 BC Many old traditions were continued in the 4th century BC, so that one can speak of a cultural continuity rather than a complete break.

Ceramics

One of the main reasons for assuming that many Mycenaean Greeks came to Cyprus from this time on is the ceramic finds. Much of the goods now produced were Mycenaean, although old forms - albeit on a small scale - continued to be produced. There were mainly deep bowls with two handles, mostly painted dark on a white background. In addition, there were also numerous very simple vessels that were not produced on the potter's wheel and that have their counterpart in Greece.

Temple buildings

At that time, monumental temples were built in the cities, which continued old traditions in the basic plan. There was an outer courtyard where the congregation might gather and a more inner part with a vestibule and the holy of holies. One example is a large temple in Palepaphos with a spacious courtyard measuring around 20 by 20 meters and surrounded by a mighty wall. At its northern end was a large portico. The temples also appear to have been production centers. A textile workshop may have existed in one temple of Kition, and the main temples of Enkomi and Kition were close to metal workshops. Some temples were adorned with ox horns carved in stone. A novelty in the cult inventory were clay masks, several of which were found. Finds of anthropomorphic figures from this period are not very common, but there were numerous cattle figures made of clay. Cult statues could not yet be identified with certainty. After all, the Horned God may have been one.

Metal goods

Other innovations were numerous types of metal objects that had not previously existed in this form on the island. The first iron objects appeared. In addition, there are new types of swords and also spears to be mentioned, which were particularly liked to be deposited in graves next to the dead, and which indicate a new self-image of the upper class. Another innovation that came from the Aegean region was the fibula , which suggests new clothing customs. Another special feature are numerous bronze, often richly decorated bases, often tripods . The four-legged specimens show figural decorations in an openwork method. These bronze bases were exported to Italy. From the late Bronze Age IIIA there are some hoards , some of which contained various kinds of metal objects, including weapons, tools, metal vessels, bronze stands, figures, bars, weights, but also scrap metal. The interpretation of this hoard is controversial. On the one hand, it could have been the hiding place of metal objects that were buried before leaving the settlements and never lifted again, on the other hand, they could also have been associated with religious rites.

The transition to the Iron Age

In the Late Bronze Age IIIB, further changes can be observed that mark the transition to the Iron Age, which is why this period is often assigned to the Iron Age . Almost all large cities were abandoned, only the urban sanctuaries apparently continued to be used. The population mostly settled next to the old urban areas or in new places. It was often the places that played an important role in the Iron Age. The reasons for the settlement shift are uncertain, perhaps the old ports have silted up. There are signs that international trade has stalled or at least continued to a very limited extent; as a result, a large part of the population became impoverished, which is mainly reflected in the sparse equipment of the graves.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Horst Klengel : Trade and traders in the ancient Orient. Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Vienna a. a. 1979, p. 133.

- ↑ Ganslmayr, Pistofidis (ed.): Aphrodites sisters. P. 8; Steel: Cyprus , p. 13.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 156-58.

- ^ AB Knapp: The Archeology of Late Bronze Age Cypriot Society: The Study of Settlement, Survey and Landscape. Glasgow 1997, ISBN 0-85261-573-6 , pp. 56-61.

- ^ AB Knapp: Sources for the History of Cyprus II, Near Eastern and Aegean Texts from the Third to the First Millennium BC. Greece and Cyprus Research Center; EJ Peltenburg: From isolation to state formation in Cyprus, c. 3500-1500 BC. In: V. Karageorghis / D. Michaelides (Ed.): The Development of Cypriot Economy from the Prehistoric Period to the Present Day , Nicosia 1996, ISBN 9963-607-10-1 , pp. 27-37.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. P. 182.

- ↑ KBo 12.38

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 183-186.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 158-161.

- ↑ ZA Stos-Gale, u. a .: Lead isotope characteristics of the Cyprus copper ore deposits applied to provenance studies of copper oxhide ingots. In: Archaemetry 39 (1997), pp. 83-123.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 166-168.

- ↑ Knapp: Cyprus , p. 423

- ^ Fulvia Lo Schiavo: The oxhide ingot from Sète, Hérault (France). In: Fulvia Lo Schiavo, James D. Muhly, Robert Maddin, Alessandra Giumlia-Mair (eds.): Oxhide ingots in the Central Mediterranean , Rom 2009, pp. 421-430.

- ↑ Mihai Rotea: The Middle Bronze Age in the Carpathian-Danube Region (19th – 14th century BC). In: Mihai Rotea - Tiberius Bader (ed.): Thracians and Celts on both sides of the Carpathians. Exhibition catalog Eberdingen , Eberdingen 2000/2001, p. 25f., Fig. 14–15

- ↑ For the exact distribution of Cypriot oxhide bars and the importance of the finds for the Bronze Age trade see Serena Sabatini: Revisiting Late Bronze Age oxhide ingots. Meanings, questions and perspectives. In: Ole Christian Aslaksen (Ed.): Local and global perspectives on mobility in the Eastern Mediterranaean (= Papers and Monographs from the Norwegian Institute at Athens, Volume 5). The Norwegian Institute at Athens, Athens 2016, ISBN 978-960-85145-5-3 , pp. 15-62.

- ↑ Serena Sabatini: Revisiting Late Bronze Age oxhide ingots. Meanings, questions and perspectives. In: Ole Christian Aslaksen (Ed.): Local and global perspectives on mobility in the Eastern Mediterranaean (= Papers and Monographs from the Norwegian Institute at Athens, Volume 5). The Norwegian Institute at Athens, Athens 2016, ISBN 978-960-85145-5-3 , pp. 15-62, especially pp. 23 f. (with further documents)

- ↑ Ganslmayr, Pistofidis (ed.): Aphrodites sisters. P. 49.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 169-171.

- ^ Image of the Rhyton ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ image of bullion God (ingot God)

- ↑ Image of the horned deity

- ↑ https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/div-classtitleopium-or-oil-late-bronze-age-cypriot-base-ring-juglets-and-international-trade-revisiteddiv/763FD09E93CC6ADB344A1C9ABE5FA50E

- ↑ Zuzana Chovanec, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Zvi Lederman: Is there opium here? Analysis of Cypriot Base Ring Juglets from Tell Beth-Shemesh. Mediterranean Archeology and Archaeometry 15, No. 2, 2015, pp. 175-189. - Online as a PdF

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 161-165.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 175-181.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 171-175.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. P. 199.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 191-196.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 201-206.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. P. 196.

- ^ Steel: Cyprus. Pp. 206-210; J.-C. Courtois, J. Lagarce, E. Lagarce: Enkomi et le Bronze Recent a Chypre. Nicosia 1986.

literature

- Lena Aström: The Late Cypriote Bronze Age: other arts and crafts. Lund 1972.

- Hector William Catling : Cypriot bronze-work in the Mycenaean world , Oxford 1964.

- Hans-Günter Buchholz : Ugarit, Cyprus and Aegean, cultural relations in the second millennium BC Chr. Münster 1999, ISBN 3-927120-38-3 .

- Herbert Ganslmayr , Alexandros Pistofidis (ed.): Aphrodite's sisters and Christian Cyprus . Frankfurt 1987, ISBN 3-8218-1717-8 , pp. 44-68.

- Vassos Karageorghis : Early Cyprus. Crossroads of the Mediterranean. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2002, ISBN 0-89236-679-6 .

- A. Bernard Knapp: The Archeology of Cyprus, From the Earliest Prehistory through the Bronze Age , Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-0-521-72347-3 .

- Louise Steel: Cyprus before History. London 2004, ISBN 0-7156-3164-0 , pp. 149-213.

Web links

- Letters from the king of Alasiya

- Review by Louise Steel, Cyprus before History at Bryn Mawr Classical Review (English)

- Cyprus in the Late Bronze Age ( Memento from October 8, 2008 in the Internet Archive )