Adem Jashari

Adem Jashari ( Serbo-Croatian Адем Јашари / Adem Jašari , born November 28, 1955 in Donji Prekaz near Srbica , FVR Yugoslavia ; † March 7, 1998 , BR Yugoslavia ) was a Kosovar-Albanian co-founder and temporary local commander of the UÇK region in the Drenica region .

life and death

schooldays

Adem Jashari attended elementary and middle school with technical specialization in his birthplace and later in Srbica .

Role in the underground militant movement

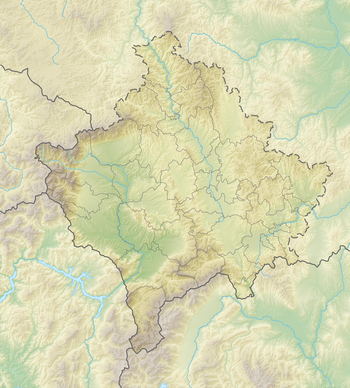

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia with the partial republics of Serbia (with the autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo ) and Montenegro

|

The residence of the Jashari family was in Donji Prekaz, a village in the Drenica region where around 1,000 people lived before the war. It became a center of the forming UÇK early on , and Jashari himself became one of its organizers and commanders in the Drenica region. The hilly Drenica region of the Serbian province of Kosovo within the Yugoslav Confederation was already almost exclusively inhabited by ethnic Albanians in the 1990s, especially since many ethnic Serb families had left Kosovo as a result of the Albanian nationalist riots of 1981 and the hostility that followed. Some of the underground fighters of the 1990s were already active in the 1980s and those who were not imprisoned made contact with Adem Jashari's militant family in Donji Prekaz, with Adem Jashari, his father Shaban Jashari and his own around the turn of the year 1989/1990 Brother Hamëz Jashari . Pleurat Sejdiu, spokesman for the UÇK London, described Adem Jashari as well prepared politically and “allergic to police uniforms”. While working with the LPRK, Adem Jashari, his friend Sami Lushtaku, and several others left Kosovo in 1990 for serious military training in Albania. Their main camp was in Labinot near Elbasan , where an Albanian army base was located. According to Shaban Shala, the training was carried out by army officers from the Albanian state, then ruled by Ramiz Alia , who officially pretended to be volunteers when training Kosovars. On his return to Kosovo, the police besieged the house of Adem Jashari, who was helped by other LPRK members in the ensuing firefight, killing one policeman and wounding two of Jashari's daughters. The police did not return to Donji Prekaz to arrest him because they feared he would shoot them again from the house.

As early as 1991, the Prime Minister of the Kosovar Albanian shadow government, Bujar Bukoshi , signed an agreement with the underground organization “ People's Movement for a Republic of Kosovo ” (LPRK), founded in 1982 , from the so-called seat of government in Ljubljana , to train guerrilla fighters . The LPRK had been in contact with “Western” secret services since 1991, and in May 1993 the first Serbian police officers were killed and others wounded in Glogovac , in the center of the Drenica region. From it later emerged, among other things, the People's Movement of Kosovo (LPK), out of which in turn the Liberation Army of Kosovo (UÇK) was founded in Switzerland in 1993 to wage the future guerrilla war. One of Adem Jashari's sons was a co-founder of the UÇK.

Adem Jashari and his brother Hamëz Jashari were often viewed as role models by the KLA members. As early as the mid-1990s, the Jashari brothers from the Drenica area were known for their clashes with the Serbian-dominated police forces, among other things, they attacked police stations several times, but also Serb paramilitaries who were already active in the Kosovo area before the Kosovo war . On July 11, 1997, Jashari and fourteen other Albanians were convicted in absentia by the court in Pristina of terrorist activity. In 1996 and 1997 armed attacks attributed to militant Albanians increased significantly.

In autumn 1997 the KLA declared the areas of Drenica and Pejë to be the first “liberated areas” in Kosovo, which dramatically increased the violent clashes. The regional presence of the KLA in the Drenica region forced the Serbian police to leave their checkpoints at night. Since 1997 at the latest, the UÇK has also had training camps in the northern Albanian regions of Kukës and Tropoja . In October and November 1997 the KLA began to present itself publicly for the first time at the funerals of its soldiers and sympathizers, at events that drew tens of thousands of people. So, again in the Drenica area, on November 28, 1997, uniformed and armed members of the UÇK appeared in public for the first time. At the funeral of Halit Gecaj, an Albanian from Kosovo, who was killed in an attack by the KLA on a Serbian police patrol in the area of Srbica (Skënderaj), they gave a speech to the mourning community of around 20,000 people in Lauša, who had come together from the Drenica area , claimed that Serbs were massacring Albanians and made a kind of "declaration of war" on the "Serbian occupation forces" which was broadcast on satellite television from Tirana that evening and which the crowd applauded. At this stage the KLA began open confrontations with Serbian police patrols in the Drenica and Peć areas. These events were also referred to as the beginning of the civil war, the first “martyr” of which Halit Gecaj was hyped up despite the unexplained circumstances of death, supported by a traditional network of informal communication that existed in rural areas of Kosovo, which included both information dissemination and myths - and the creation of legends. The government viewed the Drenica region as a hotbed of "Albanian terrorism". One focus of police attention in Drenica was on Donji-Prekaz, and in particular on the estate of Adem Jashari, who rose to prominence as a local KLA leader in 1997.

At the beginning of 1998 the KLA intensified its attacks on Serbian and Montenegrin colonists in Kosovo and all ethnic Albanian political leaders were threatened with death if they signed an autonomy agreement with Serbia. The Drenica region had become a UÇK-controlled area, in the middle of which, for example, the old Serbian monastery Devič, which was run by nuns, was only a "tiny island of Serbian territory" in 1998.

Fighting in Prekaz and Likošane and death in the police operation in Prekaz

Selected locations in the Drenica (red) and other regions (yellow) that are related to clashes between the KLA and the security forces Large map: Kosovo, Small map: Albania |

Adem Jashari's death is related to the first major clashes between the UÇK and the Serbian security forces. They occurred again in late February and early March 1998 in the UÇK stronghold of the Drenica region and are connected to the visit of the US special envoy Robert Gelbard to Belgrade:

When the clashes between the KLA guerrillas and the Serbian security forces escalated in early 1998 after the KLA announced on January 4, 1998 that it was the Albanian armed force that would fight until the unification of Kosovo with Albania January 1998 the police arrest Adem Jashari, whose clan played a key role in the large influx of the KLA in the Drenica region. When the police surrounded the area early in the morning to arrest Adem Jashari, according to his father, Shaban Jashari, they had to withdraw after a firefight because the KLA came to his aid. This made it clear that Ibrahim Rugova's claim that the UÇK was simply the result of a bizarre conspiracy by the "Serbs" was incorrect. In the following two months the number of attacks on the police and on so-called Albanian "collaborators" escalated. According to official figures, the number of attacks jumped from 31 in 1996 and 55 in 1997 to 66 in January and February 1998 alone. According to the International Crisis Group in March 1998, UÇK had assumed responsibility for the deaths of 21 citizens in Kosovo since 1996, including five police officers, five Serbian civilians and eleven Kosovar Albanians accused of collaborating with the Serbian government. On February 23, 1998, the US special envoy Robert Gelbard condemned the actions of the KLA and called them a terrorist group. On the other hand, he classified the actions of the Serbian security forces as a corresponding “police force” against the terrorist KLA and also announced some minor concessions to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. This was taken as a diplomatic sign of the approval of the Serbian government to fight the UÇK.

A few days after this meeting with Gelbard, on February 27 or 28, the first large-scale operation of the Serbian special police against UÇK centers began, including in the town of Likošane in the Drenica region, around ten kilometers from Donji Prekaz. The fighting lasted for a week until the police concentrated their forces around the houses of the Jashari clan in Donji Prekaz on March 5:

On February 28, a firefight broke out in Likošane (alban .: Likoshan or Likoshani) near Ćirez (Alban .: Çirez) between four KLA fighters and a police patrol. According to Shaban Shala, a militant LPK and UÇK member who also worked under-cover as a human rights activist, the UÇK members were ambushed by the police. According to official information, however, Adem Jashari carried out two ambush attacks on Serbian police patrols . Five cars with UÇK reinforcements arrived, including Adem Jashari. Three policemen were killed in the fight. During further actions on the same day, 26 Kosovar Albanians from Likošane and Ćirez were also killed by the police. According to official information, a total of four police officers and 16 terrorists were killed. The army was not involved, contrary to claims made by some news agencies and newspapers.

The police have now decided again to arrest Adem Jashari, who had killed a police officer a few years earlier and was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment in absentia by the Pristina court in July 1997. On March 5th and 6th, the police carried out an operation in Donji Prekaz, in which Adem Jashari was killed:

The police initially moved into an empty former ammunition factory on the hill behind the Jashari property, from where several houses of various branches of the Jashari clan in Donji Prekaz and the property of the Lushtaku family, also affiliated with the UÇK, were within fire range. Early in the morning of March 5, a column of police entered the village from one side while the police were using artillery from the factory. The Lushtaku family escaped and the police asked the Jashari family to come out. Two people who fled the house were shot dead by the police. No one appeared from Adem Jashari's house and the police then continued firing, including with artillery. A total of 58 ethnic Albanians were killed in Donji Prekaz and in nearby Lauša (Llausha). Adem Jashari was killed on his estate. A gunshot wound was found on his neck. Other family members and other people, including an estimated 18 women and 10 children under the age of 16, were also killed during the police operation. According to witness reports, his parents, Shaban (74) and Zaha Jashari (72), as well as his brothers, Rifat and Hamza (47) and their families, including the three girls, Blerina (7) and Fatime, had died in the same house with Adem Jashari (8) and Lirije (14) and four boys, Blerim (12), Besim (16), Afete (17) and Selvete (20). In neighboring Ćirez too, Serbian security forces are said to have cracked down on civilians. According to reports from survivors, units of the notorious Arkans paramilitary force , the "tigers", were involved. The combat areas were cordoned off, and aid organizations were not allowed to care for the wounded. Neither the Serbian police nor the Kosovar Albanian fighters, who reportedly used women and children as “shields” during these fighting, showed no consideration for civilians.

After the police publicly announced on March 9 that they would bury the bodies themselves if the family members did not do so immediately, but the family members did not comply with the request in the hope of an autopsy , the police buried 56 bodies on March 10 near Donji Prekaz, ten of which had not yet been identified. On March 11, the bodies were exhumed . A list compiled by the Council for the Defense of Human Rights and Freedoms lists 42 people identified as having died in Donji Prekaz from March 5-7 (including 41 people with the surname Jashari) and six identified People who perished in the nearby village of Lauša (including no person with the family name Jashari).

Meaning and afterlife

Aftermath of the Killing of Adem Jashari and his family

The police operation of March 1998 against the Jashari family has gone down in history as a “massacre” that the KLA created a martyr with the death of Adem Jashari and, according to Tim Judah, triggered the “Kosovo uprising”. Wolfgang Ischinger took the position that the "drama" of the Kosovo conflict could not be understood without February 28, 1998. Human Rights Watch concluded that the violence in the Drenica region "marked a turning point in the Kosovo crisis."

Among the fatalities was Adem Jashari, a UÇK commander who had become a legend, was considered one of the founders of the UÇK, was highly regarded as a symbol of the new military resistance and was killed or "murdered" together with almost his entire family (Petritsch & Pichler , 2004). Amnesty International ruled that it appeared to have no intention of detaining armed suspects, but rather to eliminate the suspects and their families. The EU envoy for Kosovo, Wolfgang Petritsch , said the attacks were aimed at wiping out entire extended families associated with the KLA. But the scientific interpretation of the events is also represented that the escalation of violence was initiated by the Kosovar Albanian side in order to disrupt the normalization process that has begun between the USA and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, “to advance the internationalization of the conflict and to promote international public opinion for Kosovo's independence to take ".

The acts of violence formed a deep cut in the engagement of international organizations in the Kosovo conflict. The international public and the media were now aware of the conflict. The escalation of violence in Kosovo was the reason for the Resolution no. 1160/1998 of the UN Security Council put of 31 March 1998. The international community imposed sanctions on the Serbian government and the UÇK, which the USA classified as a terrorist group at the beginning of the violence, was not destroyed by the operation of the Serbian police, but strengthened and its support among the ethnic Albanian population increased. The internationalization of the conflict has now been promoted by the USA, the so-called "Balkan Contact Group", the ICTY and the UN Security Council .

The localized military defeat had turned into a political success in the civil war. Up to this point the KLA had neither a political program nor an accepted representation, no international recognition and no control over important military forces. But reports of “massacres” and myths of national martyrs made the KLA the driving force behind national liberation in the eyes of a growing number of young Kosovar Albanians, and the KLA was able to emerge as a major political power for the first time. As a result, village militias formed all over Kosovo, many of which were actually connected to parallel structures, but nevertheless called themselves UÇK. This was also interpreted as the beginning of the war.

In addition, the conflict, which had been characterized by the conflict between Kosovar Albanians and the Serbian state apparatus, developed into an interethnic conflict, as there were increased attempts by Kosovar Albanians to intimidate Kosovar Serbs, who felt pressured to leave Kosovo should, while the two ethnic groups were previously used to living together or side by side.

In the period that followed, armed Kosovar Albanians increasingly staged attacks on Serbian police stations. The Serbian police held back with their reactions and avoided villages that were dangerous for them, so that the KLA was able to declare the area around Lauša a "liberated area". Thus, the acts of violence in this first phase of the civil war had resulted in overall success for the KLA, as they established themselves in their heartland, the Drenica area, and could carry out operations from this KLA “bastion” and tried to “close” other areas to free".

Adoration as hero and martyr

As a result, Adem Jashari was revered as a martyr and celebrated as a hero in Albanian culture, especially in Kosovo. Posthumously after Kosovo's independence was declared unilaterally by the Kosovar Albanian side on February 17, 2008, he was awarded the title "Hero of Kosovo". Pristina International Airport was named after him.

According to an Ipsos study from 2011, Adem Jashari is by far the most valued “hero” in Kosovo's public opinion. 60% of all Kosovar Albanians consider him the most important modern “hero”, followed by Ibrahim Rugova with 10%. Jashari and Rugova represent two competing national narratives in Kosovo. While one narrative is based on the legacy of peaceful resistance to the system under Milošević in the 1990s under Rugova's leadership, the other reading is based on the memory of the armed resistance, such as that of the UÇK and Adem Jashari as one of their fighters is symbolized. The figure of Jashari is connected to the politics of the PDK . The PDK and the War Veterans Association were the main carriers of the identity discourse, which focused on the armed struggle of the UÇK and the memory of Adem Jashari as a national hero and advocated the construction of a collective memory of martyrdom. The PDK used the image of Jashari as a basis for its political legitimation and made him an emblem of the freedom and independence of Kosovo. The Kosovo conflict and war of 1998 and 1999 as well as the UÇK narratives are of central importance in the school history books of grades 5 and 9 in Kosovo. For example, a 9th grade history book portrays Adem Jashari as a “legendary commander and a symbol of resistance and inspiration for national freedom and independence”, accompanied by a photo of Jashari wearing a military uniform and a machine gun. In a history book of the fifth grade, a photo by Adem Jashari accompanies the text on the UÇK, which is presented as the "Army that protects the Kosovar Albanians from the Serbian army and police."

After the war, the practice of visiting the Jashari family's property was revived in Kosovo. The remains of the badly damaged house, his grave and the graves of the other family members who were killed became a kind of place of pilgrimage for hero worship for many ethnic Albanians. According to scientific assessments, the Jashari family's estate in Prekaz became a downright “sacred” place for all Albanians and for the political reproduction of the collective and its political elites, albeit without religious significance. Schools organized visits to the Jashari family cemetery as part of extracurricular activities for students. Albanians living in the diaspora or in neighboring countries have now seen Prekaz as a mandatory travel destination. After ballots or on major national and state holidays, leaders of the Kosovo government laid wreaths in the cemetery and visited surviving members of the Jashari family. In 2005, the Assembly of Kosovo passed a law for the “Adem Jashari” memorial complex, which declared Adem Jashari's property a place of “ontological, anthropological-historical, cultural and civic importance” for all ethnic Albanians. According to a study, Kosovar Albanians consider the Jashari family memorial to be the most important monument in Kosovo. In addition, every year on March 5th, 6th and 7th the government sponsors a memorial event, Epopeja e UÇK ("Epic of the UÇK"), to celebrate the armed struggle of the Jashari family as resistance of the family on those days in 1998 .

- Gallery: Adem Jashari Memorial in Prekaz:

A statue of Adem Jashari was erected in Srbica, in the region considered to be the cradle of the "independence movement". Not far from there is his grave, which has become a kind of “shrine of independence”. In Pristina, the capital of the - depending on the legal interpretation - the Serbian province of Kosovo or the sovereign state of Kosovo, Adem Jashari honors a large-scale poster at the Youth and Sports Palace.

In Tirana, the capital of Albania, shortly before Jashari's birthday, a six-meter-high Adem Jashari statue by the artist Muntaz Dhrami was inaugurated in 2012, replacing a bust of Adem Jashari at the same location. Hashim Thaçi , Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, announced that "Commander Adem Jashari and his warriors" had given importance to freedom and independence in Kosovo. On behalf of Adem Jashari's relatives, Rifat Jashari declared on the occasion that his family had died for the “most sacred ideal of Albanianism”, national unity. The Prime Minister of Albania, Sali Berisha , says at the inauguration ceremony:

“We have come here from all Albanian countries. We are proud of you, Commander, and we promise today that we will do everything possible to make the dream of national unification a reality, as the noblest and most European dream of this country. "

After the war, songs and poems were written about Adem Jashari. Tim Judah described the spirit in which the fighters of the UÇK waged their war of liberation, also based on a song about the legendary Kachak ( kaçak ) Azem Galica , who had fought in the Drenica for the independence of his clan, i.e. not yet a national one. The old song was adapted in honor of the slain brothers Adem and Hamza Jashari as the continuation of the struggle that went on from generation to generation and has the passage:

"We clean our scorched land with blood"

In this sense, Judah does not see Adem Jashari as an ideologically motivated guerrilla, but in the tradition of the Kaçak (German: "bandits", "rebels"), armed gangs operating from the mountains that have been in existence since the end of the occupation by the In 1918, after their defeat by the Serbs and since the subsequent establishment of the new Yugoslav state as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the ensuing takeover of power by the Serbs in Kosovo, the Central Powers began repeatedly attacking Serbian posts or units and robbing the cattle of Serbian farmers . With a quote, Judah Adem Jashari compares these kaçaks, who were last known during the First and Second World Wars and whose center was in the Drenica region as early as 1918, from where they called for a general uprising against Serbian rule in May 1919:

"He liked getting drunk, going out and shooting Serbs."

Source for Kosovo-Albanian nation building and state legitimation of Kosovo

The use of the figure Adem Jashari in many different forms, in school history books, on memorial sites and days of remembrance, pilgrimages to his family's estate, has made Adem Jashari and his family a new epic of nation building for Kosovar Albanians and also made the memory of the 1998 and 1999 wartime as the main source of legitimacy for a Kosovo state.

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Elsie, A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History , IB Tauris, 2012, London & New York, p. 222, ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3 .

- ↑ Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 26.

- ↑ a b c d e Heike Krieger: The Kosovo Conflict and International Law: An Analytical Documentation 1974-1999 , Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-521-80071-4

- ↑ a b c d e Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 18.

- ↑ Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , p. 43.

- ↑ a b c Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , pp. 110f.

- ^ A b c Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 261, footnote 24.

- ↑ a b c d e Tim Judah: The Serbs: History, Myth, and the Destruction of Yugoslavia 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-300-08507-9 , pp. 320f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War Using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 275.

- ↑ Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , p. 132.

- ↑ a b c d e Federal Republic Of Yugoslavia - A Human Rights Crisis in Kosovo Province, Drenica, February-April 1998: Unlawful killings, extrajudicial executions and armed opposition abuses ( Memento of August 30, 2013 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento of August 30, 2013 on WebCite )), Amnesty International, Document Series A. # 2. AI Index: EUR 70/33/98, June 1998.

- ↑ a b c d Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 27.

- ↑ a b c d e f Heinz Loquai: The Kosovo conflict - ways into an avoidable war: the period from the end of November 1997 to March 1999. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6681-8 , p. 22nd

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j The Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report - Conflict - International Response - Lessons Learned. Oxford University Press 2000, ISBN 0-19-924309-3 , pp. 67f.

- ↑ a b Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , pp. 136f.

- ^ Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 274.

- ↑ a b Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , p. 42.

- ↑ a b c Heinz Loquai: The Kosovo Conflict - Ways to an Avoidable War: the period from the end of November 1997 to March 1999. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6681-8 , p. 23.

- ^ A b The Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report - Conflict - International Response - Lessons Learned. Oxford University Press 2000, ISBN 0-19-924309-3 , p. 147.

- ↑ Heinz Loquai: The Kosovo conflict - ways into an avoidable war: the period from the end of November 1997 to March 1999. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6681-8 , pp. 45, 170.

- ↑ a b c d e Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , pp. 137f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petritsch, Karl Kaser, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova: Myths, data, facts. 2nd Edition. Wieser, Klagenfurt 1999, ISBN 3-85129-304-5 , p. 211.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , pp. 138-140.

- ↑ a b Tanjug news agency: BBC: Kosovo killings: Belgrade's official version of events. BBC News, March 12, 1998, accessed May 3, 2013 .

- ↑ a b c d e Heinz Loquai: The Kosovo Conflict - Ways to an Avoidable War: the period from the end of November 1997 to March 1999. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6681-8 , p. 24 .

- ↑ Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 19.

- ↑ Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 28.

- ^ A b Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 31.

- ^ A b Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , pp. 28-30.

- ^ A b Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 276, footnote 63.

- ↑ Fred Abrahams (Frederick Cronig Abrahams), Elizabeth Andersen, Humanitarian Law Violations in Kosovo , Human Rights Watch, New York et al., October 1998, ISBN 1-56432-194-0 , p. 32.

- ^ The Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report - Conflict - International Response - Lessons Learned. Oxford University Press 2000, ISBN 0-19-924309-3 , p. 68, footnote 4 (p. 344.), with reference to: Police Operation in the Drenica Area, March 5-6,1998 , The Humanitarian Law Center.

- ↑ a b c d e Heinz Loquai: The Kosovo conflict - ways into an avoidable war: the period from the end of November 1997 to March 1999. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6681-8 , p. 24f .

- ↑ How Germany got into the war ( Memento from August 30, 2013 on WebCite ) . Zeit Online, May 12, 1999, by Gunter Hofmann, archived from the original .

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Petritsch, Karl Kaser, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova: Myths, data, facts. 2nd Edition. Wieser, Klagenfurt 1999, ISBN 3-85129-304-5 , p. 212.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petritsch, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova - The long way to peace. Wieser, Klagenfurt et al. 2004, ISBN 3-85129-430-0 , p. 106.

- ↑ Wolfgang Petritsch, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova - The long way to peace. Wieser, Klagenfurt et al. 2004, ISBN 3-85129-430-0 , p. 277.

- ^ A b The Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report - Conflict - International Response - Lessons Learned. Oxford University Press 2000, ISBN 0-19-924309-3 , pp. 69f.

- ^ The Independent International Commission on Kosovo: The Kosovo Report - Conflict - International Response - Lessons Learned. Oxford University Press 2000, ISBN 0-19-924309-3 , pp. 55, 69f.

- ↑ a b Ulf Brunnbauer , Andreas Helmedach, Stefan Troebst: Interfaces: Society, Nation, Conflict and Memory in Southeastern Europe , Oldenbourg Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-58346-5

- ↑ a b c NATO Says It's Prepared to Keep Peace in Kosovo ( Memento June 4, 2013 on WebCite ) , The New York Times, December 9, 2007, by Nicholas Kulish, archived from the original .

- ^ Paul R. Bartrop , A Biographical Encyclopedia of Contemporary Genocide - Portraits of Evil and Good , ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, California 2012, ISBN 978-0-313-38679-4

- ↑ a b c d Vjollca Krasniqi, Kosovo: Topography of the Construction of the Nation . In: Pål Kolstø (ed.), Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe (English), Southeast European Studies, Ashgate Publishing, Farnham 2014, ISBN 978-1-4724-1916-3 .

- Jump up instead of resignation - Youth in Kosovo ( Memento from August 30, 2013 on WebCite ) , Deutschlandradio Kultur, by Klaus Heymach, February 4, 2013, archived from the original .

- ↑ a b c New statue for Adem Jashari in Tirana ( Memento from August 30, 2013 on WebCite ) , www.top-channel.tv, November 27, 2012.

- ↑ a b Tirana, inauguration of Adem Jashari's statue ( memento from August 30, 2013 on WebCite ) , news.albanianscreen.tv, November 27, 2012, archived from the original .

- ↑ Politicians Take Control of History in Albania ( Memento from August 31, 2013 on WebCite ) (English). Balkan Insight (BI), June 25, 2013, by Besar Likmeta / Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), archived from the original .

- ^ Carl Polónyi: Salvation and Destruction: National Myths and War using the Example of Yugoslavia 1980-2004. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8305-1724-5 , p. 272.

- ↑ Tim Judah: Kosovo: War and Revenge. 2nd edition, Yale University Press, New Haven et al. 2002, ISBN 0-300-09725-5 , p. 101.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Petritsch, Karl Kaser, Robert Pichler: Kosovo - Kosova: Myths, data, facts. 2nd Edition. Wieser, Klagenfurt 1999, ISBN 3-85129-304-5 , pp. 99-106.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Jashari, Adem |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jashari, Adem Shaban (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Yugoslav-Kosovar co-founder of the paramilitary organization UÇK |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 28, 1955 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Donji Prekaz / Prekaz i Poshtëm |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 7, 1998 |