Scuole

Spiritual and charitable corporations, guilds and guilds or associations of foreign country teams were referred to as scuole in the Republic of Venice . In the rest of Italy (for example in Naples ) the name for comparable institutions was: Confraternita ( brotherhood ) or Arciconfraternita (arch brotherhood ). The synagogues were also accepted as such and are therefore also called scuola in Venice . One of the most important tasks of such an association was the care of the dying and their burial as well as the care of the bereaved, as well as general welfare for the poor.

In addition to the influential and wealthy Scuole grandi , there were a large number of Scuole piccoli , in which traders and craftsmen came together. Marin Sanudo narrates that there were around 210 large and small schools in 1501. After the fall of the Republic of Venice , the Schools were dissolved by a decree of Napoleon (1806/07). At the urging of the citizens, only the Scuola Grande di San Rocco escaped this . The Scuola Grande dei Carmini (S. Maria del Carmelo) was re-established in 1840.

The building in which a scuola is located is also called a scuola .

The great brotherhoods (scuole grandi)

The scuole grandi - a translation of "large schools" is misleading - which arose from the medieval scourge brotherhoods , were, in contrast to the scuole piccole , the "small schools", which were organized professionally or as a country team, charitable associations with strong members and finances, which usually had more than 500 members. The management of the school and the administration of the property was in the hands of the bourgeoisie ( cittadini ). Venetian nobili , clergy and foreigners could be accepted as simple members, whereby only men were allowed in the Scuole grandi.

All schools were organized similar to the model of the political organization of the Mark Republic with a general assembly (chapter), limited in time - mostly for one year - elected boards (with the scuole grandi die banca from the guardian grande , its deputy vicario , the one responsible for the processions Guardian da matin and the secretary Scrivan ), assigned councilors who supervised the work (twelve Degani di tutt'anno elected in spring and twelve Degani di mezz'anno elected in autumn ) and numerous subordinate functionaries, whose paid offices also provided brethren in need were. Wealthy brothers often financed construction work or works of art for the school privately.

The activities of the Scuole Grandi were monitored by the Council of Ten , the decisions of their executive boards required confirmation by this council body with far-reaching powers.

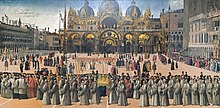

In addition to the charitable work, representation and the display of splendor were the most important focus in the work of the school. The members wore the same costume ( toga veneta ) as the Venetian nobili , in different designs and colors for the functionaries. They organized lavish processions and competed among themselves in the splendor of their meeting buildings and their external appearance, especially during processions.

In the 17th century there were six Scuole Grandi, each with representative brotherhood buildings:

- Scuola Grande di San Teodoro; founded in 1258, upgraded to Scuola Grande in 1552; first located near San Marco, later near San Salvador, initially in an Albergo of the convent (today S. Marco 4826), finally after 1555 the own building, which still exists today, was built after 1555

- Scuola Grande di Santa Maria della Carità, founded in 1260, today Accademia

- Scuola Grande di San Marco , founded in 1261; first at Santa Croce, since 1437 at Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista , founded in 1261; initially based in San Aponal, moved to San Giovanni Evangelista in 1307

- Scuola Grande di Santa Maria della Misericordia (or della Valverde), founded in 1308

- Scuola Grande di San Rocco , founded in 1478 from the merger of a Brotherhood of Rochus near San Giuliano and one near Santa Maria Gloriosa; Multiple changes of seat: In 1486 the Scuola rented the former palace of the Patriarch of Grado on the Rio del Vin (about where the Casa Ravà is today (S. Polo 1099)), since 1489 it has been located near Santa Maria Gloriosa

Two more were added in the 18th century:

- Scuola Grande dei Carmini

- Scuola Grande di San Fantin , also called Scuola Grande di San Girolamo.

The small brotherhoods (scuole piccole)

Tasks and organization

In Venice you can still find many places whose names indicate the professional activities that were carried out here. Many of these activities were of great importance for the life of the people and therefore also of the city. They ranged from simple forms of trade such as covering daily needs, to the sought-after, specialized professions such as silk weaver or goldsmith . There are still traces of this variety of professions that can be found everywhere on the house walls and that are used today as street names.

Professional life was regulated based on the division of labor, with modern ideas of division of labor and strict delimitation of the trades not directly transferable to historical conditions. The individual professions were summarized in the so-called scuole artigianali , which were professional associations , similar to the commercial guilds or guilds . The difference between guilds / guilds and the Venetian school is mostly unclear in the literature. They protected those who belonged to it, codified customary law such as the training of apprentices, the rights and obligations of members, but also took care of private concerns of professionals such as assistance in the event of illness and need. In order to attend school, one had to lead a decent life and have extensive professional knowledge.

Each profession was strictly separated from the others, had its fixed and inviolable limits in the execution of the work, and it was forbidden by law to exceed them. Within each group there were three categories of membership, the lowest of which was that of garzonato . Anyone enrolling in a profession had to complete an apprenticeship which, depending on the type of profession, lasted between five and seven years. With the supervisory authority, the Giustizia Vecchia, all agreements or contracts between the apprentices, the garzoni , and the masters were registered. These contracts are an extremely interesting source today, they give us information about the individual garzoni , their age, parents, origin and naming of the master, the guild mark of his workshop and the duration of the contract.

The custom of registering the contracts dates back to the second half of the 13th century, although the competent authority had already issued a warning to the Pechers' craft on August 1st, 1301 not to accept an apprentice until he was not trained by the master the quaternum dominorum justiciarum , the register available at the Giustizia Vecchia , was inscribed. The law of March 10, 1396 finally obliged any branch of the profession to register all training contracts with the court.

In the first period, the garzone was instructed in the basic knowledge of the chosen profession; the age of the members of the garzonato varied according to the type of professional association. After the level of the garzone one reached the one of the lavoranza , which lasted two to three years and during which one was confronted with all the problems of the profession. At the end of the apprenticeship, after passing a practical exam la Prova d'Arte , you got the status of Capo Maestro .

In Venice, however, the brotherhoods of the individual orders and national groups were also named as scuoles .

Each profession was under the protection of a saint , whose feast day was celebrated very solemnly. The professional statutes , the so-called Mariegole (from madre and regola ) give precise insights into the nature of the school, the caring purpose and the rules that were used to maintain, develop and carry out the same. The rules, which were initially passed down orally, were recorded by the Ufficio della giustizia vecchia from the 13th century onwards and in 1278 40 professional statutes were summarized in a register, which was preserved and published with additions extending up to 1330. Two copies of this set of rules were created, one was deposited with the court, the second remained at the school. Most of the Mariegole have disappeared; the specimens that have survived to our day are kept in the Biblioteca Correr.

The schools were under the direct supervision of a jurisdiction created for this purpose at the end of the 12th century. On November 22nd, 1261, the Great Council created a new department, which was called Giustizia Nuova to distinguish it from the previous one . It became necessary because of the increasingly complex structure of the individual professions and the impossibility of comprehensive control by just one authority. The previous court, the Giustizia Vecchia, was responsible for large-scale business, while the Giustizia Nuova took care of the concerns of small businesses and local suppliers.

Some of the schools had their own buildings, but for the most part they were located in the various churches, where they had their own altar and could use separate rooms. There was a communal grave for the members of the profession. In their archives they kept documents, the constantly renewed Mariegola and the penelo , their flag, which was carried in the processions. All schools had an insegna , an emblem painted on fabric or a wooden board , which indicated the trade they were engaged in. This emblem was kept in the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi near Rialto, today there are around forty copies in the Museo Correr .

List of professional groups (selection)

| Scuola di | Profession or activity | Seat in |

| Acquaroli | Transport of drinking water from the Brenta to the city | Campo San Basilio |

| Acquavitieri | Brandy seller | San Stin Church (from 1601) |

| Barbieri | Beard trimmers, but also surgical interventions | from 1465 at Campo Santa Maria dei Servi, building demolished |

| Barcaroli | Ferry traffic with gondola across the Grand Canal | at different churches, depending on the place of practice |

| Barileri e Mastelleri | Bucket and barrel producers | |

| Bastazi della Dogana da Terra | Load carriers for the customs stations | Sant'Aponal Church |

| Batti e Tiro Oro | Gold and silver rackets | Building next to the San Stae Church |

| Beccheri | butcher | Cà Grande Querini, altar in the Church of San Matteo |

| Beretteri | Cap makers and hat makers | San Biagio Church |

| Boccaleri | Producers of pots, pans and cups | Church Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari |

| Burchieri da Legna | Transports on wooden boats | |

| Burchieri da Cavafanghi | Garbage collection on boats | Church of Sant'Andrea della Zirada |

| Calafatti | Ship carpenters | Santo Stefano Church |

| Caldereri | Foundry workers, bell casting, hearth casting | from 1294 Church of San Marcuola , then San Luca |

| Calegheri | Shoemaker, processing of new leather | Scoletta dei Calegheri |

| Zavateri | Shoemaker, processing of used leather | Scoletta dei Calegheri |

| Calzeri | Producer and trade in and in silk stockings | Church of San Fantin |

| Carboneri | Coal traders, coal carriers | San Salvador Church |

| Carteri | Playing card maker | |

| Casaroli | Cheese producers | |

| Casselleri | Chest Maker | |

| Castelletti | Servants in lottery records | |

| Cerchieri da botte | Barrel hoop manufacturer, cooper | from 1259 San Trovaso |

| Cesterei | Basket weaver | Church of San Biagio |

| Filacanevi alla tana | Hemp rope processing for the arsenal | from 1488 San Giovanni in Bragora |

| Luganegheri | Sausage seller | Altar in San Salvador |

| Medici fisici | doctors | from 1671 Teatro Anatomico at Campo San Giacomo dall'Orio |

| Mercanti | Merchants | from 1374 Madonna dell'Orto |

| Mercanti di vino | Wine merchant | Altar in Madonna dell'Orto |

| Sabioneri | Sand and stone carriers | |

| Saoneri | Soap boiler | |

| Sartori | cutter | |

| Squeraroli | Gondola shipyard workers, formerly all private shipbuilding workers | |

| Tagiapiera | Stone cutters, stonecutters | Building next to the Sant'Aponal church, 2nd floor |

| Strazzarolli | Resellers of used fabrics, scrap dealers | |

| Travasadori de ogio | Refill of oil in bottles | San Giacomo di Rialto |

| Naranzieri | Seller of citrus | |

| Osti e Locandai | Osteria host (limited to 20 throughout the city) | Church of SS. Filippo e Giacomo (but also others) |

| Pescatori | Fisherman | Church of S.Nicolò dei Mendigoli |

| Pistori | Bakers, only confectioners, no contract bakers | |

| Salumieri | Seller of salted meat and fish | |

| Tintori | Dye (wool, silk) | from 1581 Church of Santa Maria dei Servi |

See also

Remarks

- ^ Scuole Scuole grandi e piccole: English Italian .

- ↑ The name Scuole grande is first recorded for 1467. See also Gabriele Köster: Artists and their brothers. Berlin 2008 p. 16, footnote 28, with further references.

- ↑ See Richard Mackenney: Tradesman and Traders. The World of the Guilds in Venice and Europe, c.1250-c. 1650 . London 1987.

- ↑ Enrico Besta , Giovanni Monticolo (ed.): I capitolari delle Arti veneziane sottoposte alle "Giustizia" e poi alla "Giustizia vecchia" dalle origini al 1330 . 3 vols. Rome 1896–1914.

- ↑ Even though they were very poor, the fishermen were very much respected, because none other than the fishermen, who were practically out and about day and night in the lagoon, knew it very well. Only at this school was the elected board of directors called the Doge, who also had a place of honor next to the Doge of Venice at official ceremonies . The Doge of S. Nicolò was assigned twelve councilors and a chancellor who managed the fishermen's guild. On September 5, 1536, the Savi alle acque decided to create a book made of expensive parchment paper in which all the fishermen's information had to be entered "in order to better understand the development and movements in the lagoon." The fishermen's lay brotherhood selected eight experts, who had to report regularly under oath on the condition and changes in the lagoon.

swell

- Marino Sanudo : Venice, Cità Excelentissima: Selections from the Renaissance Diaries of Marin Sanudo . Ed. by Patricia H. Labalme, Laura Sanguineti White. JHU Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-80188765-9

literature

- Silvia Gramigna, Annalisa Perissa: Scuole grandi e piccole a Venezia tra arte e storia. Confraternite di Mestieri e devozione in sei itinerari. Grafiche 2am, Venezia 2008, ISBN 978-88-904285-0-0 .

- Gabriele Köster: Artists and their brothers. Painter, sculptor and architect in the Venetian Scuole Grandi (until about 1600). Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-78612548-8 (also: Berlin, Free University, dissertation, 2003).

- Cesare Zangirolami: Storia delle chiese, dei monasteri, delle scuole di Venezia rapinate e distrutte da Napoleone Bonaparte. G. Zanetti, Venezia 1962.