Peace of bread

The peace of bread was a greg on February 9, 1918 . Separate peace concluded between the Central Powers ( German Empire , Austria-Hungary , Bulgaria and Ottoman Empire ) on the one hand and the Ukrainian People's Republic on the other during the First World War . The treaty was concluded in Brest-Litovsk against the background of the peace negotiations taking place there between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers. He brought urgently needed food deliveries to Germany and Austria-Hungary, but not to the extent originally hoped for.

Starting position

Immediately after the October Revolution of 1917, the new government of Soviet Russia proclaimed the “ Decree on Peace ” on November 8th . The Bolsheviks wanted by a withdrawal from the First World War, a foreign policy respite and thus time to prepare for the impending civil war in the interior win. On December 3, Soviet Russia and the German Empire began armistice negotiations, on December 7, the Soviet government ordered the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Caucasus Front against the Ottoman Empire and Persia, on December 15, an armistice was concluded, and peace negotiations began on December 22 the front city of Brest-Litovsk .

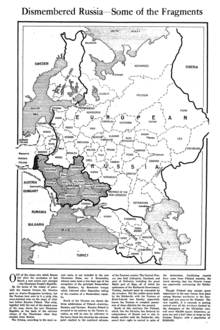

Troops of the German Reich and Austria-Hungary were already militarily occupying large parts of the west of the former Russian Empire ( Poland , Baltic States), and in some unoccupied regions counter-governments had already emerged that no longer followed the Soviet Russian government in Petrograd (Ukraine, Finland, Caucasus).

In the fight against the Soviet Republic ( Soviet Ukraine ) formed in December 1917 by the Bolshevik People's Committee of Ukraine in Kharkov , Donetsk , Poltava , Yekaterinoslav and Krivoy Rog , the Ukrainian Central Rada in Kiev had proclaimed a Ukrainian People's Republic . Against this in turn, a Soviet republic was formed by Rumcherod in Odessa in January 1918 , which allied itself with Kharkov and Petrograd. The Central Powers hoped to take advantage of this conflict to put pressure on Soviet Russia on the one hand to agree to a disadvantageous peace dictate, but on the other hand also to make Ukraine itself dependent.

However, German and Austro-Hungarian interests vis-à-vis the Ukraine were not congruent, which in turn was due to German-Austro-Hungarian differences on the Polish question. Austria-Hungary favored the trialist Austropolitan solution with the inclusion of Galicia, but the German Empire had its own annexation intentions towards Poland. In order to put pressure on Austria-Hungary, the chief of staff of the German Eastern Front, Max Hoffmann , began preliminary negotiations with the Central Rada on January 2, 1918 without Austria-Hungary. In exchange for German arms aid, the Ukrainian diplomats offered food, but asked Austria-Hungary to connect the Polish district of Cholm as well as Bukovina and Eastern Galicia to the Ukraine. Austria-Hungary and his army, in turn, urgently needed the food deliveries from Ukraine, the food situation was desperate. Hunger riots have already broken out in Vienna and other cities, followed by the January strike . Hoffmann only seemingly opposed the Ukrainian demands. He promised the cession of Cholm, but advised the Ukrainians with regard to Bukovina and Eastern Galicia to “only” demand their autonomy as a newly formed crown land within Austria-Hungary, but to insist on it. For the Austrian Foreign Minister Ottokar Czernin , who joined on January 4th but had to take Polish and Hungarian interests and irritations contrary to the Ukrainian demands into consideration, the preliminary negotiations are therefore extremely complicated. The peace conference could not begin until January 9th.

negotiations

After joint talks had started on January 9, 1918, the chairman of the Central Rada delegation, Vsevolod Golubovich , declared on January 10 that the Soviet government in Petrograd could not make peace on behalf of Ukraine. The Soviet Russian negotiator Leon Trotsky then initially agreed to an independent Ukrainian delegation on January 12, although the Central Rada had already lost power to the Bolsheviks in large parts of Ukraine by that time.

After German demands had been submitted, on January 18, 1918, the Soviet Russian side initially asked for an interruption. The Ukrainian Central Rada delegation also traveled back to Kiev on January 20 and proclaimed the independence of Ukraine there, which led to the Ukrainian-Soviet war and a Soviet-Russian intervention in the Ukrainian civil war.

After the Kiev arsenal revolt broke out on January 29th, representatives of Soviet Ukraine also appeared in Brest-Litovsk on January 30th and demanded a right to participate. However, referring to Trotsky's decision, the Central Powers declared that they had only recognized the Central Rada as a partner in dialogue and would continue to negotiate only with it. Golubovich, meanwhile Prime Minister of the People's Republic, which was in the process of dissolution, only managed to make his way from Kiev to Brest-Litovsk on January 31.

With the help of the Sitscher riflemen set up by Austria-Hungary in Galicia , the Central Rada was able to put down the revolt in Kiev by February 4, but had to flee the Ukrainian capital on February 8, 1918 before the Bolsheviks advancing again.

The powerless Ukrainian Central Rada delegation agreed more indulgently, but time was of the essence for the exhausted German western front and the starving Austrian army. In Berlin on February 6, the German Foreign Minister Richard von Kühlmann , OHL boss Erich Ludendorff , Czernin and representatives of the Austro-Hungarian Army High Command had agreed that, 24 hours after the conclusion of a separate peace with Ukraine, the delegation of Soviet Russia would ultimately also conclude a treaty to request or break off negotiations.

Terms of contract and the term "peace of bread"

It was finally contractually stipulated that the German Reich and Austria-Hungary should receive almost 1 million tons (60 million poods ) of grain, 400 million eggs and 50,000 tons of cattle (live weight) from the Ukrainian People's Republic by July 31, 1918 , as well as bacon, Sugar, flax, hemp, manganese ores etc. In return, German and Austro-Hungarian troops were to provide military assistance to the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Kholm district was assigned to Ukraine.

The agreement that Eastern Galicia should receive autonomy within Austria-Hungary as a Ukrainian state (crown land) by July 31, 1918, was packaged in a secret additional article.

The term "peace of bread" coined by Czernin goes back to a speech given by the Viennese mayor Richard Weiskirchner when Czernin returned from Brest on February 13, 1918: "They bring us the peace of bread of the East ...". The term "bread peace" used today is misleading in that it suggests that it was a matter of extorting Ukrainian grain for the home front of the Central Powers. In reality, it was a bilateral treaty that can be seen as a major success for the existentially threatened Central Na Rada in the fragile Ukrainian state.

consequences

Although Czernin had assured the delegation of Soviet Russia that the separate peace concluded with Ukraine was not a hostile act against Soviet Russia, the agreed German-Austrian ultimatum was presented to it on February 10, 1918. After its lapse, the Central Powers began an offensive known as Operation Faustschlag on February 18 with 500,000 men. German-Austrian troops occupied the Ukraine. In the north, German troops advanced against Petrograd. It was only on February 23 that the Red Army, which was hastily deployed after the breakup of the Russian Army, was able to stop the German advance at Pskov to a limited extent. After the fall of Zhytomyr in Ukraine, the Soviet government finally accepted the ultimatum the following day. In the Ukraine, however, German-Austrian troops continued their offensive and German troops captured Kiev on March 1, 1918. On the same day, negotiations between the Central Powers and Soviet Russia were resumed and on March 3, 1918, the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaty was finally concluded. With this treaty, Soviet Russia also had to officially recognize the Ukrainian People's Republic and stop supporting Soviet Ukraine. Austrian troops were able to conquer Odessa on March 12 and Yekaterinoslav on April 4, German troops Donetsk and Krivoy Rog on March 19, Poltava on March 30 and finally Kharkov on April 8.

Austria hoped not to be pushed aside completely by Germany in Ukraine, so that it would be able to pursue its goals in the east. After all, 250,000 men of the Austro-Hungarian Eastern Army had moved into the Ukraine to carry out the "peace of bread".

Immediately after the conclusion of the treaty, the Council of Ministers of the Regency Kingdom of Poland resigned in protest against Cholm's resignation, and a general political strike against the Central Powers broke out in Warsaw. The "peace of bread" with Ukraine thus contributed significantly to the alienation of the Poles from the Central Powers, with whom they had previously fought together against Russia and the Entente. In the Ukraine, too, the resistance against the German-Austrian occupation, organized by partisans, grew.

On April 28, 1918, the German military administration in Kiev arrested Prime Minister Golubowitsch, dissolved the Central Rada and thus the Ukrainian People's Republic and installed Pavlo Skoropadskyj as the hetman of the Ukrainian state . Nevertheless, the occupation forces and their Ukrainian allies failed to collect the agreed deliveries of food. Up to November 1918 only about 120,000 tons of grain had been delivered to the Central Powers. The reasons for the inadequate deliveries were the too high estimates of the Central Powers and the chaotic internal conditions in Ukraine.

The agreed autonomous Ukrainian crown land East Galicia-Bukovina was therefore not established. At the same time, the agreement on the partition of Galicia was not granted reluctantly on the Austrian side and only in an effort to conclude the "peace of bread", but corresponded to the Austrian solution that Prime Minister Stürgkh had been striving for for years. Under Polish pressure and with reference to the non-compliance with the delivery quantities of food, Austria-Hungary canceled the corresponding secret article on July 4, 1918. Instead, after the fall of the Habsburg monarchy in November 1918, the West Ukrainian People's Republic was founded in East Galicia , but by May 1919 East Galicia was also in Polish hands, and in the Paris Peace Treaty of 1919 all of Galicia was assigned to Poland. In order to win the Poles as allies against the Bolsheviks, the Ukrainian People's Republic renounced Eastern Galicia in 1920, whereupon the Ukrainian population of Galicia rose against Kiev and joined the Ukrainian Soviet Republic newly founded by the Bolsheviks in Charkow . However, in the Peace of Riga in 1921, Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine had to cede eastern Galicia to Poland.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Potjomkin, p. 411 f.

- ↑ a b Potjomkin, pp. 392-395.

- ↑ All in all, Poles formed a small majority of the population in Galicia compared to Ukrainians, Germans and Jews. From a regional point of view, however, the Poles were in the majority only in western Galicia (between Krakow and Lemberg), and to the east of Lemberg mainly Ukrainians lived.

- ↑ Potjomkin, pp. 395, 401 and 403.

- ↑ Potjomkin, p. 397 f.

- ↑ a b c d e Potjomkin, p. 402 f.

- ↑ Frank Grelka: The Ukrainian national movement under German occupation rule in 1918 and 1941-42. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-447-05259-7 , p. 260; and Peter Broucek (Ed.): A General in Twilight. The memories of Edmund Glaise von Horstenau. Volume 1: Kuk General Staff Officer and Historian. Böhlau, Vienna 1980, ISBN 3-205-08740-2 , p. 458.

- ↑ Frank Grelka: The Ukrainian national movement under German occupation rule in 1918 and 1941-42. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-447-05259-7 , p. 94.

- ^ Potjomkin, pp. 405 and 425.

- ↑ Oleh S. Fedyshyn: Germany's Drive to the East and the Ukrainian Revolution 1917-1918 . New Brunswick / New Jersey 1971, p. 163.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner : The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Graz / Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-222-12454-X , p. 543.

- ↑ Potjomkin, p. 425 f.

- ^ Wolfdieter Bihl: Austria-Hungary and the peace treaties of Brest-Litovsk. Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1970, ISBN 3-205-08577-9 , p. 124.

- ^ Heinz Lemke: Alliance and rivalry. The Central Powers and Poland in the First World War. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1977, ISBN 3-205-00527-9 , p. 282.

literature

- The Hetman Charter for the whole of Ukraine based on the decision of the Council of Ministers on the ratification of the peace treaty between Ukraine and Germany. (Ukrainian: . Грамота Гетьмана Всієї України видана на підставі ухвали Ради Міністрів про ратифікацію Мирового Договору України з Німеччиною ) Київ: Видання "Державного Вісника" 1918 року.- 32 с.

- Vladimir Petrovich Potemkin : History of Diplomacy. Volume 2: The Diplomacy of Modern Times (1872-1919). SWA-Verlag Berlin 1948, pp. 379-412 and 425-432.

- Erhard Stölting : A world power is breaking up. Nationalities and Religions of the USSR. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-8218-1132-3 , p. 81.