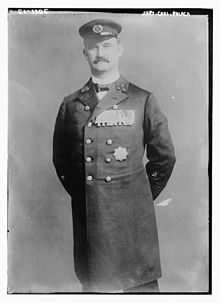

Charles August Polack

Charles August Polack (born January 29, 1860 in Grimma ; † November 17, 1934 in Bremerhaven ) was a navigator and captain of the North German Lloyd (NDL) and was responsible for operating some of the most important transatlantic passenger steamers before the First World War . At that time he was one of the most famous and respected German merchant ship masters.

biography

Origin, education and first years

Polack was born in Grimma, Saxony, as the son of Captain Peter Andreas Polack. His family soon moved to Cuxhaven , as his father worked there as a harbor master and water schout after an active life as a captain . A professional publication in the international Nautical Magazine in 1863 made him famous. Polack left his parents' house at the age of 15 and went to sea. He hired on various Hamburg merchant sailing ships and came to East Asia and South America. After completing his nautical training, Polack applied as a young officer at North German Lloyd in 1886 , as he saw the best opportunities for a successful future with this shipping company. For him, the decisive factor in this choice was the successful conclusion of the Reichspoststampfervertrag (Reich Mail Steamship Agreement) of 1885 for Lloyd. With this, the company was awarded the contract for important long-distance mail steamship routes. This also included government subsidies . He got the job he wanted and was second mate of the express steamer Ems when, at the risk of his life , he was able to save four survivors of the British sailor Hebe , which was sinking in heavy seas . For this he received a high distinction from Queen Victoria in 1890 . On December 18, 1891 he was the second mate of the steamer Spree involved in the rescue of the 149 passengers and crews of the British mail steamer Abyssinia , which sank on fire off Newfoundland , and was subsequently awarded by the Liverpool Shipwreck & Humane Society . He also put out a fire on the Spree itself, which might have broken out due to a short circuit next to the cabins of the passengers in a sideboard. Later he saved two people who were floating in an open boat and was honored for this too. Polack, who was described as a humorous, jovial personality, received further awards from the Spanish King, the Emperor of Japan, the Emperor of China and several German kings and princes. He spoke excellent German and was fluent in English, French and Italian. This talent opened many doors for him on the international stage.

Captain since 1900

In July 1900 he received his captain's license and was entrusted with the management of Aachen . His first mission was to transfer troops to China . During his stay on land in his home country, he lived in the then still independent market town of Lehe.In October 1907, he accomplished the nautical masterpiece, the twin-screw express mail steamer Kaiser Wilhelm der Große , steered only with the two screws after losing the rudder in stormy seas, safely from New York via Plymouth and Cherbourg to Bremerhaven. The ship was only one day late with an average speed of 18 knots and around 2300 nautical miles . For this achievement he received the Prussian Order of the Crown, third class, from Kaiser Wilhelm II in the same year . When the Mayor of New York , William Jay Gaynor, was shot on August 9, 1910 on the Kaiser Wilhelm the Great lying in the harbor of Hoboken, Polack, who was almost standing by, prevented a mass panic on the ship. In December of the same year, Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, traveling to New York, lost her port propeller on the Newfoundland Bank. Repairing the ship in Hoboken would have delayed the return trip by Christmas mail, which Polack wanted to prevent. After the port technicians had not found any immediate danger to the ship despite the missing screw, the return journey was started. The express mail steamer reached Bremerhaven punctually, with Polack maneuvering at the intermediate stations in Plymouth and Cherbourg without the help of the delayed tugs in order not to lose any more time. At the end of 1912 he was awarded the honorary title of Vice Admiral in the Lloyd fleet by his employer . As captain, Polack was responsible for the Aachen , Werra , King Albert , Princess Irene , Kaiser Wilhelm the Great and George Washington before he was given command of the Crown Princess Cecilie , a sister ship of the Kaiser Wilhelm the Great , in 1913 .

1914 to 1917

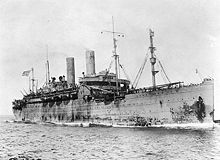

When the Crown Princess Cecilie arrived in Hoboken on March 19, 1914, Polack had completed his hundredth voyage as captain and was honored in both Hoboken and Bremen. On July 28, 1914, Crown Princess Cecilie left New York on schedule under the command of Polack for Bremerhaven. There were 1216 passengers on board, as well as gold bars and coins valued at 15 million US dollars. The gold was intended for Parisian and British banks. On the high seas, the captain received news of the impending start of the war. His shipping company also asked him to turn back immediately. Since the situation that follows was part of several judicial investigations, it is well documented. The ship ran into the small port of Bar Harbor in the state of Maine on the night of August 4, 1914 and anchored in the bay there. The reason for not heading for New York or Boston , Polack stated that he had intercepted the communications link from the British cruiser Essex to Halifax and had thus been forewarned that the British were planning to monitor the major American ports. The Crown Princess Cecilie and her crew remained at anchor in the bay until the morning of November 6, 1914. Polack had the ends of the chimneys tied with a black ribbon as temporary protection against British attacks in order to simulate a ship of the English White Star Line . Only after a US protection guarantee to Captain Polack that Crown Princess Cecilie would not be attacked by any enemy warship, did the steamer leave Bar Harbor in escort with the US destroyer Warrington and a coastal defense cutter and was confiscated in the port of Boston in Massachusetts , because the Cecilie should be secured for the plaintiffs in the following legal proceedings for the non-fulfillment of the gold transport to Europe. This happened even though the American government had declared that, in principle, no ship of the German merchant navy would be confiscated and that the Germans could dispose of their fleet at will.

After the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, Polack and his remaining crew were taken prisoner of war . This had no effect on the trials against the captain and North German Lloyd. On May 7, 1917, the suits of the two New York financial services providers Guaranty Trust Co and National City Bank, as well as two passengers from New York and Brussels, were dismissed by the Supreme Court. All lawyers had based their charges on breach of contract. However, the court found that the master had dutifully safeguarded the safety of all interests and correctly assessed the dangers when he turned the ship in the Atlantic.

It took until May 7th, the day the trial against Norddeutscher Lloyd ended, before the American authorities were able to give their consent to the seizure of Crown Princess Cecilie by the United States Shipping Board . It was planned to repair the damaged machinery of the passenger steamer after it had been established in early February 1917 that the crew had destroyed the machinery in order to make it more difficult for the Americans to take it over. The damage determined by a US marine engineer affected all cylinders of the quadruple expansion machines. The Germans had cut out a large piece of steel there and also knocked off the mountings for the cylinder heads. Since it was not possible in the USA to produce the components manufactured in Germany from scratch, the installation of a new machine system was advocated. According to Captain Polack, he had received the sabotage order from an official of the German embassy in Washington and had it carried out on the night of January 31, 1917. With the reactivation, the ship was renamed USS Mount Vernon and converted into an American troop transport.

1920 to 1934

After the end of his captivity, the NDL appointed Captain Polack director of the company's own spa facilities on the East Frisian island of Norderney . After the loss of its ocean fleet in the First World War, the shipping company endeavored to reduce the number of older captains and officers that were now in excess and to entrust them with new tasks. Polack took his retirement as an opportunity to work again as an active seaman. The US shipping company United States Lines made use of his above-average nautical knowledge as a sea pilot.

One of the first officers Polack had trained was Leopold Ziegenbein , whom he held in high esteem and always visited when he was anchored in Bremerhaven. Ziegenbein was the captain of the Bremen on November 16, 1934 and lay at the Columbuskaje in Bremerhaven the day before his departure . As usual, Polack was there. After a long farewell drink, he said goodbye at midnight, fell into the sea on the way home and drowned. Polack was buried in the Bremerhaven cemetery in Wulsdorf .

literature

- Reinhold Thiel: The history of the North German Lloyd 1857-1970 . Hauschild, Bremen 2004, ISBN 3-89757-166-8 .

- Hartmut Bickelmann : Bremerhaven personalities from four centuries. A biographical lexicon . Bremerhaven City Archives, Bremerhaven 2003, ISBN 3923851251 .

- Tilo Wahl / Bernhard Wenning: Paul Wiehr and Charles Polack. Two captains of the German shipping companies HAPAG (Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft) and NDL (Norddeutscher Lloyd) . In: Orders and Medals. The magazine for friends of phaleristics , publisher: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ordenskunde , issue 105, 18th year, Gäufelden 2016. ISSN 1438-3772.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The New York Times, December 17, 1934, p. 19.

- ↑ a b c Hartmut Bickelmann: Bremerhaven personalities from four centuries . A biographical lexicon . Bremerhaven City Archives, 2003, ISBN 3923851251 , p. 248.

- ^ Official Journal of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg , 112, 1891, p. 401.

- ^ Peter Andreas Polack: The Eastern Route to China or Japan, in the Western Pacific . In: Nautical Magazine XXXII, 1863, pp. 113-115.

- ^ A b The New York Times, March 15, 1914, p. 4.

- ↑ a b c Hartmut Bickelmann: Bremerhaven personalities from four centuries. A biographical lexicon . Bremerhaven City Archives, 2003, ISBN 3923851251 , p. 249.

- ^ Edwin Drechsel: North German Lloyd Bremen, 1857-1970; History, Fleet, Ship Mails , Volume 1, Cordillera Pub. Co., 1995, ISBN 1895590086 . P. 27.

- ↑ a b c Hartmut Bickelmann: Bremerhaven personalities from four centuries. A biographical lexicon . Bremerhaven City Archives, 2003, ISBN 3923851251 . P. 223.

- ^ Fritz Gansberg (Ed.): Maritime accidents from recent times. Decisions of the Oberseeamt and the Maritime Offices (= Scientific People's Books for School and House 18), Alfred Jansen, Hamburg / Berlin 1913. pp. 79–86; Hartmut Bickelmann: Bremerhaven personalities from four centuries. A biographical lexicon , Bremerhaven City Archives, 2003, ISBN 3923851251 . P. 223.

- ↑ Reinhold Thiel: The history of the North German Lloyd 1857-1970 . Volume 3, Hauschild, 2004, ISBN 3-89757-166-8 , p. 128.

- ↑ Mertens, Eberhard (Ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975, ISBN 3487081105 . P. 65.

- ↑ The New York Times, April 2, 1915, p. 4.

- ↑ Mertens, Eberhard (Ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975, ISBN 3487081105 . P. 75.

- ^ Arnold Kludas : The history of the German passenger shipping. Destruction and rebirth 1914 to 1930. Ernst Kabel Verlag, Munich 1989. ISBN 382250047X . P. 36

- ↑ Mertens, Eberhard (Ed.): The Lloyd Schnelldampfer. Kaiser Wilhelm the Great, Crown Prince Wilhelm, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Crown Princess Cecilie. Olms Presse, Hildesheim 1975, ISBN 3487081105 . P. 78 (newspaper clippings).

- ↑ The New York Times, December 2, 1914, p. 4.

- ↑ a b The New York Times, May 7, 19174, p. 5.

- ^ The New York Times, February 7, 1917, p. 1.

- ^ The New York Times, February 18, 1917, p. 1.

- ↑ Ekhart Berckenhagen: Shipping in the world literature: a panorama from five millennia . Ernst Kabel Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 382250338X . P. 216.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Polack, Charles August |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German navigator, captain of the North German Lloyd |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 29, 1860 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Grimma |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 17, 1934 |

| Place of death | Bremerhaven |