Daniel Wilson (prehistoric)

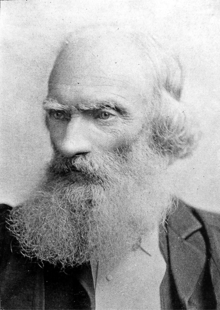

Daniel Wilson (born January 5, 1816 in Edinburgh , † August 6, 1892 ) was a Scottish prehistoric scientist , ethnologist , author and 3rd President of the Canadian University of Toronto .

life and work

Scotland and England: Artists and Prehistorians (1835-1853)

Daniel Wilson was the son of the wine merchant Archibald Wilson and Janet Aitken. Daniel was raised as a Baptist, attended Edinburgh High School , then from 1834 the University of Edinburgh , but he preferred to study as an engraver with William Miller the next year . In 1837 he went to London to become a self-employed illustrator . There he worked for the painter William Turner . In both London and Edinburgh, where he returned in 1842, he tried to live as a writer , writing reviews , but also popular books on the Pilgrim Fathers , on Oliver Cromwell , as well as articles for magazines and art reviews for the Edinburgh Scotsman . He had married Margaret Mackay († 1885) on October 28, 1840, with whom he had two daughters.

Wilson's Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Time , based in part on works from his youth, primarily woodcuts and engravings of architectural details and cityscapes, contained a rather unscientific history of the city. The third edition was published in 1875.

Inspired by Walter Scott and by the pre-British peculiarities of Scottish culture, he came across archaeological sources such as bone finds. As honorary secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland , he visited archaeological sites from 1847 and corresponded with collectors.

In 1849 he put the holdings of the Society of Antiquaries together in a compendium, for which the museum enabled him to write The archeology and prehistoric annals of Scotland . This created the first coherent overview of all known Scottish artifacts. His system distanced itself from the compilation of curiosities and rarities that had been in use up until then. He considered the archaeological remains to be the equivalent of the geologists' fossils. Wilson first introduced the word prehistory to the sciences in 1851 . He believed not only to be able to establish epochs following the example of geologists, but to be able to reconstruct inferences about attitudes and attitudes, beliefs and rites of cultures long past. In doing so, he adopted the three-part division into the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages, which had been developed in Denmark. At the same time he tried to relate this division of epochs to Christianization in order to interlink history and prehistory. Using skull measurements, he believed he could see that other peoples had lived in Scotland before the Scots. He resisted the assumption of his contemporaries that every highly developed culture goes back to Roman or Scandinavian influence, but everything that has an original effect on the British. In order to establish archeology as a science, he believed in a close connection with ethnology.

In 1851, Wilson received his only degree, an honorary lld from the University of St Andrews . In 1853 he received the Chair of History and English Literature at University College in Toronto in Canada, which was still British at the time. He was assisted by Lord Elgin , the governor of Canada, who was also a member of the Society of Antiquaries .

Canada: archeology, ethnology, anthropology, college management (1853-1892)

With the move to Canada, Wilson's interests shifted, especially since he was separated from artifacts and colleagues. On the other hand, his ethnological interest increased. This is likely to have developed through the opportunities offered by research into Indian cultures and strengthened by colleagues. Wilson joined the Canadian Institute in 1853 and published its periodical, the Canadian Journal: a Repertory of Industry, Science, and Art between 1856 and 1859 . From 1859 to 1860 he was President of the Society, a function in which he directed its focus even more strongly to geology and archeology, but also to literary criticism. Some of the members of society, such as the painter Paul Kane , the explorer Henry Youle Hind or Captain John Henry Lefroy of the Royal Engineers, had traveled far in this vast country. Wilson particularly supported Paul Kane and George William Allan , collectors of indigenous artifacts. What they had in common was that they did not recognize the intrinsic value of indigenous cultures so much as their alleged analogy to the life of the original Europeans in prehistoric times.

Measurements of the skull became Wilson's passion, and he was concerned with the question of whether the races had different origins or whether they had developed from a common race, i.e. whether there was a polygenesis or a monogenesis .

One of Wilson's acquaintances, a doctor from Philadelphia named Samuel George Morton , attributed spiritual and moral qualities to the peculiarities of the skulls or their former carriers. He claimed that races were actually different kinds . The conclusions drawn from this type of polygenesis, and the justification for slavery derived from it, repelled Wilson, and they offended his scientific skills. He was appalled by the widespread notion that it was ridiculous that blacks should come from the same root. For him, who grew up in a family who rejected slavery and felt obliged to the Enlightenment, the cultural forms were an expression of the respective traditions and living conditions, not a "racial character". In several articles he attacked Morton's thesis that the North American Indians all had the same skull proportions by showing that, on the contrary, there was enormous diversity. He also realized that numerous skulls had been altered by diet, skull deformation, and certain burial rituals.

Furthermore, Wilson's activity determined the assumption of a monogenesis, a unity of mankind and the great importance of American indigenous cultures for prehistoric mankind. On this basis his work Prehistoric Man was created. Researches into the Origin of Civilization in the Old and the New World . He dealt with water transport, metallurgy , architecture and fortress construction, ceramics, but also intoxicants and superstitions, in order to show that various forms of expression could arise from a general inspiration. Despite all differences, he believed that all human beings were capable of progress and that this ability did not depend on a biological predestination, but on social learning and the environment. At the same time, progress is not an absolutely necessary process, because people are free in their actions and can fall back into wildness. In discussions about the mounds , he compared the tomb of a chief of the Omaha , who was buried with his horse, with the tomb of a Saxon with his chariot (p. 357): “For man in all ages and in both hemispheres is the same; and, amid the darkest shadows of Pagan night, he still reveals the strivings of his nature after that immortality, wherein also he dimly recognizes a state of retribution. "(For man is the same at all times and in both hemispheres; and even in the midst In the darkest shadow of pagan night he shows his nature's striving for immortality, in which he at the same time darkly recognizes a state of retribution.).

Wilson dealt with the fate of the inferior nations, whereby North America seemed to him to be a gigantic laboratory for racial intermingling: this intermingling had long taken place in Canada to a much greater extent than is generally believed. For the polygenists, the fact that they assigned the races to different species meant that their mixed cultures must by definition be sterile. But precisely the mixed French-Indian population that arose in Canada, the Métis , seemed to Wilson in some respects to be superior to both original races. In addition, the Métis seemed to him to be an indication of the fate of the Indians, that all indigenous peoples would become extinct. Therefore he opposed the isolation of tribes in the so-called Indian Reserves , because this would prevent them from being absorbed into a new human race. For him, the isolation of individuals and the end of the tribes were the prerequisites for the ability to compete with the whites as individuals. This pattern of thought later became a major part of American Indian policy .

In contrast to Charles Darwin , whose theory of evolution through natural selection implied a continuity between animal and human intelligence, Wilson pointedly contrasted morality, reason, the ability to accumulate and pass on experience with what he believed to be the fixed, mechanical instincts of animals. This in turn contrasted with the fact that he partially accepted human evolution and a very old human culture.

Henry Youle Hind discredited Wilson as an armchair anthropologist who had worked without field work. In fact, Wilson had only made one trip to Lake Superior in 1855 to study natural copper deposits. Instead, he went to museums in Philadelphia , New York, and Boston to examine skulls. In view of the mounds , he also believed that the huge earthworks were due to a race of moundbuilders that had been driven away by the Indians. He also corresponded very intensively with Indian agents . He made European ethnology known in North America. Given that Wilson was skeptical of Darwin's theses, one of Wilson's students, William Wilfred Campbell , said his teacher was too old and conservative to be bothered by the growth of the science in the last decades of the century.

Wilson continued to write about migration and intermingling, the artistic skills of indigenous peoples, the relationship between brain size and intellectual skills. He began to doubt that the size of the brain would be anything to say about this. Wilson, who was left-handed and retrained as a child, looked at the question of why the majority of people were right-handed, whether it was a social habit or an expression of physiology. He concluded that the left hemisphere , which controls the right hand, developed earlier.

But Wilson also dealt with completely different subjects in his publications. In Though Caliban. The missing link , he dealt with Shakespeare's creation, a being between brute and human, and the imaginative inventions of evolutionary science of his time. In Chatterton. A Biographical Study , Wilson described the life of the young poet Thomas Chatterton who, like himself, had tried his luck in London, but who desperately chose to commit suicide. In 1881 Wilson said that Chatterton was his favorite work, even before Caliban and the third edition of the Prehistoric man from 1876.

But Wilson increasingly took over tasks of university administration and science policy . As early as 1860, it was not University College President John McCaul who defended the house, but Wilson. He himself became president of the college on October 1, 1880, and of the university from 1887 to 1892.

Since 1853 the college was responsible for teaching, the university for exams and awarding of titles. With the construction of the gothic building of the University College , built from 1856 to 1859 , to which Wilson had contributed designs for gargoyles and carvings, the financial resources were exhausted. This is how the Wesleyan Methodist Church came to the fore, which in 1859 prompted the Legislative Assembly , Parliament, to investigate college mismanagement. Wilson and Langton had to appear before the committee, Egerton Ryerson, the Superintendent of Education for Upper Canada , spoke out against the unjust income monopoly, because in his opinion the income should actually be distributed among all colleges. Instead, a “temple of privilege” has developed, led by a “family compact of gentlemen”; he sharply criticized the unnecessarily cluttered building and the waste of public funds. He presented Cambridge and Oxford as role models for classical subjects and mathematics, as opposed to University College, which offered far too many options in science, history and modern languages. He also doubted that Christian education could thrive in a “godless” institution.

Wilson, in his reply of April 21, 1860, strengthened the Scottish model of higher education with its wide range of offerings, which is able to prepare students for a variety of fields. The exemplary English universities listed, however, are only accessible to a privileged class. Wilson's own brother George (1818-1859), a chemist, who died the previous year, had been kept away from university for years because he had refused to sign the Creed and Submission to the Church of Scotland . Wilson rejected the sectarianism of colonial society and discussed that public funding of this kind would only perpetuate class and religious disputes, whereas in a non-denominational system religious beliefs would not be an obstacle to scientific collaboration. In his eyes, on the other hand, the sciences support scripture and ecclesiastical interference hinders the search for truth. He thought his opponent Ryerson was an unscrupulous and Jesuit-false intriguer ("the most unscrupulous and jesuitically untruthful intriguer I ever had to do with"). Wilson fought against the integration of Victoria College into the university by all means . For him it was a Methodist conspiracy, backed by politicians hoping for Methodist voters. Only after his death did the universities take on teaching functions.

Particularly difficult issues during Wilson's tenure were the employment of Canadian-born residents and the right to have a say in politics. This proved to be particularly complicated when it came to admitting women to college. Although they were allowed to take an exam from 1877 onwards, they were not allowed to attend classes. In 1883, Wilson turned down requests from five women to attend University College. Emily Howard Stowe and the Women's Suffrage Association took over her case through William Houston, Parliamentary Librarian and Member of the University Senate, and through the two MPs John Morison Gibson and Richard Harcourt , who were also members of the Senate. Wilson intervened on March 12, 1883 with Education Secretary George William Ross against a corresponding draft resolution. Wilson advocated higher education for women and stressed that he himself had helped found the Toronto Ladies' Educational Association in 1869 . He gave the same readings there as at college, but believed that learning together young men and women distracted too much from the subject matter. He preferred a women's college along the lines of Vassar or Smith in the United States. Wilson later admitted that sexual innuendos in Shakespeare's works were of major concern to a mixed class. He informed Prime Minister Oliver Mowat that he would not do anything about the matter unless he was forced to do so, which in fact happened on October 2, 1884.

Wilson was facing increasing pressure from all sides. In 1886 he prevented the union leader Alfred F. Jury from speaking in the Political Science Club because he not only disapproved of the "communists" and "infidels", but because he feared criticism from the Methodists. He also turned against politically motivated appointments and appointments.

On February 14, 1890, a fire destroyed the eastern half of the controversial University College building, including the library and Wilson's lecture notes. Most of the time he was out of college from mid-July to September, traveled back and forth to Edinburgh and spent many summers with his daughter Jane (Janie) Sybil in New Hampshire . When he died, he left an inheritance of $ 76,000, half of which was in stocks and bonds. According to her father's instructions, Jane Sybil destroyed all of her father's papers, except for a diary.

Raised a Baptist, Wilson became an Anglican Evangelical. In Toronto he supported the Church of England Evangelical Association . In 1877 he was one of the founders of the Protestant Episcopal Divinity School , later Wycliffe College . He was also associated with the Young Men's Christian Association in Toronto, of which he was president from 1865 to 1870.

In 1875 he was elected a member ( Fellow ) of the Royal Society of Edinburgh .

reception

In Great Britain, Wilson was remembered as a scientist and man of letters, as well as a pioneer of Scottish prehistory, but in Canada his career as a science organizer who fought against religious influences as well as political influence was paramount. In addition, its importance in history, anthropology and ethnology was considered secondary.

It was not until after 1960 that historians who followed Darwin's influence in Canada and ethnologists who studied the Canadian roots of their discipline began to revive Wilson's scientific opus.

Works (selection)

- Memorials of Edinburgh in the Olden Times , 2 vols., Edinburg 1848, 3rd ed., Edinburgh 1875 ( digitized ).

- The Archeology and Prehistoric Annals of Scotland , Edinburgh, London 1851. ( digitized version ), 2nd edition in 2 volumes, 1863.

- Prehistoric Man. Researches into the Origin of Civilization in the Old and the New World , London 1863, 2nd edition 1865 ( digitized ), 3rd greatly expanded edition 1876.

- Chatterton. A Biographical Study , MacMillan, London 1869.

- Caliban, the Missing Link , London 1873 ( digitized ).

- Spring wildflowers , London 1875, 2nd ed.

- Reminiscences of Old Edinburgh , David Douglas, Edinburgh 1878 (an extension of his earliest work) ( digitized ).

- Coeducation. A letter to the Hon. GW Ross, MPP, minister of education , Toronto 1884 ( https://archive.org/stream/coeducationlette00wils#page/n1/mode/2up Digitalisat).

- William Nelson. A Memoir , Edinburgh 1889 ( digitized version ).

- The Right Hand: Left-handedness , MacMillan, London 1891 ( digitized ).

literature

- Calr Berger: WILSON, Sir DANIEL , in: Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- Bennett McCardle: The Life and Anthropological Works of Daniel Wilson (1816-1892) , thesis, University of Toronto, 1980 (Wilson's works, pp. 173-191).

- Gale Avrith: Science at the margins: the British Association and the foundations of Canadian anthropology, 1884-1910 , phd thesis, University of Philadelphia, 1986.

- William Stewart Wallace: A History of the University of Toronto, 1827-1927 , Toronto 1927.

- Douglas Cole: The origins of Canadian anthropology, 1850-1910 , in: Journal of Canadian Studies 8.1 (1973) 33-45.

Remarks

- ^ The Canadian album. Men of Canada; or, Success by example, in religion, patriotism, business, law, medicine, education and agriculture; containing portraits of some of Canada's chief business men, statesmen, farmers, men of the learned professions, and others; also, an authentic sketch of their lives; object lessons for the present generation and examples to posterity (Volume 1) (1891-1896) p. 13.

- ↑ The archæology and prehistoric annals of Scotland , Edinburgh,. 1851

- ^ Prehistoric Man. Researches into the origin of civilization in the Old and the New World , 2 vols., Cambridge and Edinburgh 1862.

- ↑ Though Caliban. The missing link , London 1873.

- ↑ Chatterton. A Biographical Study , London 1869.

- ^ Martin L. Friedland: The University of Toronto. A History , 2nd ed., University of Toronto Press, Toronto 2013 (1st ed. 2002), p. 69.

- ^ Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. (PDF file) Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed April 24, 2020 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wilson, Daniel |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Scottish prehistoric, ethnologist, author and 3rd President of the Canadian University of Toronto |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 5, 1816 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Edinburgh |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 6, 1892 |