Description de l'Égypte

Description de l'Égypte ( French : Description of Egypt ) is the title of a famous collection of texts and images that was created as a result of the Egyptian expedition of Napoléon Bonaparte (1798–1801). It is considered to be an essential impetus for the emergence of Egyptology as a science. The full title is: “Description de l'Égypte ou recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expedition de l'Armée Française publié par les ordres de Sa Majesté l'empereur Napoléon le Grand”. ( French : description of Egypt or collection of the observations and researches carried out in Egypt during the expedition of the French army, published on the orders of His Majesty, Emperor Napoleon the Great.)

Egypt as a destination

Officially, the campaign served the goal of liberating the Egyptian people from the rule of the Mamluks and Ottoman suzerainty and making the achievements of Western civilization accessible to them. The political motive behind this was to transform Egypt into a French province, to increase and stabilize France's influence in the Mediterranean region and thus indirectly hit the more successful colonial power England . Napoléon's personal motivation was to avoid his opponents in Paris for a while and to increase his own fame by conquering legendary Africa .

Napoléon not only had political and military ambitions, but was also a mathematician and was interested in science and the arts. From the beginning he combined his military planning for the campaign in Egypt with scientific and cultural goals. The “Description de l'Égypte” is largely due to his initiative. This part of his company was linked to a number of earlier activities: In 1787 the comprehensive travelogue “Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie” by the Comte de Volney was published (the author was later one of Napoléon's civilian companions in Egypt). Throughout the 18th century, scholars had gained new knowledge about the Orient , which resulted in the establishment of an Ecole Publique in the National Library in 1793 , where Arabic , Turkish and Persian were taught. In 1795 the Institut National de France was established , at which oriental studies should also be carried out.

The research company

In addition to the war costs for Napoléon's company, the Directory - at that time the decisive authority of the French Revolution - finally approved considerable sums for non-military activities: 215,000 livres for scientific equipment and over 25,000 livres for the purchase and transport of a special library, including 550 Volumes personally selected by Napoleon.

The campaign began in May 1798 and around 35,000 soldiers took part. There were also around 500 civilians, including 21 mathematicians, 3 astronomers , 17 engineers , 13 naturalists and mining engineers, 4 architects, 8 draftsmen, 10 humanities scholars, and 22 typesetters who could use Latin , Greek and Arabic letters. After a battle at the pyramids of Giza , which was extremely costly for the Mamluks , Cairo was captured. Napoleon believed the campaign had already been won. In 1798 he founded an Egyptological institute ( Institut d'Égypte ) in Cairo . The researchers working here were given the task of examining every imaginable aspect of life in Egypt, both historical and current.

The climatic conditions were extremely unfavorable, the everyday living conditions unusually harsh. Nevertheless, the mostly young scientists and students did their work effectively and with sustained enthusiasm for their commander-in-chief Bonaparte. Vivant Denon , previously director of the Louvre in Paris and now responsible for the Egyptological Institute, wrote: " A single word from the hero ... was enough for my decision to go with him " and apparently also set the mood of his staff. About the situation on the ground, in the rear of an army in a state of war, Denon reported that they had crossed a country “ which, apart from its name, was practically unknown to the Europeans; consequently, it was all worth recording. Most of the time I made my drawings on my knees. Some I had to do standing up, and others even on my horse ... ”. Archaeological finds were systematically registered and restored if possible, but irrigation systems , agriculture and handicrafts were also examined . The French orientalists in the expedition tried to establish a trusting relationship between the representatives of the two different cultures by exchanging ideas with the inhabitants in their everyday language. In the confrontation with the real living conditions, the idealizing idea of Egypt as a paradise on earth, widespread in Europe, was quickly lost.

After the turbulent course of the war in various locations in the region, most recently decisively defeated by a British army, the French had to leave Egypt again in the late summer of 1801. Napoleon had already withdrawn from the expeditionary force two years earlier in a secret operation in order to continue his career in France. The French scientists refused to leave their work in Egypt, even though they were temporarily threatened with death. Eventually the English left them the written material, but confiscated the art objects, including the Rosetta Stone . It had been found in the Nile Delta and, with its triple inscription - hieroglyphics , demotic symbols and Greek letters - seemed to provide the key to deciphering the ancient Egyptian picture writing. The stone went to the British Museum in London as spoils of war , copies of the inscription also made it to Paris. After a long scientific competition, the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion was the first to decipher the system of hieroglyphics in 1822 .

The publication

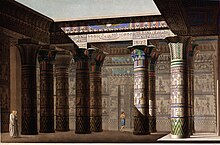

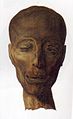

In February 1802 Napoléon arranged for the extensive scientific and artistic results of his militarily failed expedition to be published. The result was a complete description of Egypt at the time of the campaign - its antiquities, but also its everyday life and its flora and fauna. The work of 400 engravers over almost 20 years resulted in 837 engraved plates with a total of more than 3000 illustrations, divided into eleven sections: five for antiquities, three for natural history, two for contemporary and one for maps. The first edition of the "Description de l'Égypte" under the direction of Francois Jomard appeared in several parts between 1809 and 1828, it comprised nine quarto volumes and 11 photo books in oversized format as well as two photo books and one volume with maps in very large format ( mammoth portfolio ) , thus a total of 23 volumes. The entire work has the character of an encyclopedia and has often been compared with Diderot's Encyclopédie . Louis XVIII , King of France since 1814, had 100,000 francs distributed to 70 employees of the plant as a token of his appreciation . The political and strategic disaster of the campaign gradually disappeared in the public consciousness behind the scope and importance of its cultural output, and in France a veritable Egyptomania developed.

A second edition, commonly referred to as édition Panckoucke , was published by Charles Louis Fleury Panckoucke in a smaller format between 1821 and 1830 and divided into 37 volumes, with many of the larger images folded into the smaller format. Most of the digital copies reproduce this second edition.

Second edition (édition Panckoucke)

- Volume 01 (1821): Tome Premier, Antiquités-Descriptions.

- Volume 02 (1821): Tome Deuxième, Antiquités-Descriptions. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 03 (1821): Tome Troisième, Antiquités-Descriptions. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 04 (1822): Tome Quatrième, Antiquités-Descriptions.

- Volume 05 (1824): Tome Cinquième, Antiquités-Descriptions. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 06 (1822): Tome Sixième, Antiquités-Mémoires. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 07 (1822): Tome Septième, Antiquités-Mémoires.

- Volume 08 (1822): Tome Huitième, Antiquités-Mémoires.

- Volume 09 (1829): Tome Neuvième, Antiquités-Mémoires et Descriptions.

- Volume 10 (1826): Tome Dixième, Explication Des Planches, D'Antiquités. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 11 (1822): Tome Onzième, Etat Moderne. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 12 (1822): Tome Douzième, Etat Moderne. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 13 (1823): Tome Treizième, Etat Moderne.

- Volume 14 (1826): Tome Quatorzième, Etat Moderne.

- Volume 15 (1826): Tome Quinzième, Etat Moderne.

- Volume 16 (1825): Tome Seizième, Etat Moderne. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 17 (1824): Tome Dix-Septième, Etat Moderne.

- Volume 18.1 (1826): Tome Dix-Huitième, Etat Moderne. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 18.2 (1829): Tome Dix-Huitième (2´ Partie), Etat Moderne. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 18.3 (1830): Tome Dix-Huitième (3´ Partie), Etat Moderne. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 19 (1824): Tome Dix-Neuvième, Histoire Naturelle, Botanique-Météorologie. ( Digitized on Google Books ).

- Volume 20 (1825): Tome Vingtième, Histoire Naturelle.

- Volume 21 (1826): Tome Vingt-Unième, Histoire Naturelle, Minieralogie - Zoologie.

- Volume 22 (1827): Tome Vingt-Deuxième, Histoire Naturelle, Zoologie. Animaux Invertébrés (suite).

- Volume 23 (1828): Tome Vingt-Troisième, Histoire Naturelle, Zoologie. Animaux Invertébrés (suite). Animaux Venteures.

- Volume 24 (1829): Tome Vingt-Quatrième, Histoire Naturelle, Zoologie.

- Volume 25 (1820): Planches: Antiquités.

- Volume 28 (182x): Planches: Antiquités.

- Volume 29 (182x): Planches: Antiquités.

- Volume 30 (182x): Planches: Antiquités.

- Volume 31 (1823): Planches: Antiquités.

- Volume 32 (1822): Planches: Etat Moderne.

- Volume 33 (1823): Planches: Etat Moderne.

- Volume 34 (1826): Planches: Histoire Naturelle.

- Volume 35 (1826): Planches: Histoire Naturelle.

- Volume 36 (1826): Planches: Histoire Naturelle.

- Volume 37 (1826): Planches: Atlas geographique.

Whereabouts of the originals

Of the 1000 sentences in the first edition in 23 volumes, around half were distributed to employees of the expedition, only 150 were freely sold. At least eleven of this first edition have survived worldwide. This includes the edition of the Institut d'Égypte founded by Napoleon in Cairo, which was destroyed in December 2011 as part of the revolutionary protests after an arson attack. In contrast to the thousands of historical documents in the institute's library, which were destroyed in the fire, the Description de l'Égypte was saved with almost no damage. In view of numerous media reports about the alleged loss of the work, the Egyptian minister of culture made it clear shortly after the fire that there were two more complete and one incomplete set of the first edition in Egypt. In 2015 it became known that since 1958 a set of the same first edition, which had been forgotten for decades, was being kept in a building of the Egyptian Embassy in Madrid, which was apparently intended as a state gift from Egypt to Spain.

gallery

literature

- Description de l'Égypte. Taschen, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3775-7 .

Web links

- Official website with the complete digitization of the work, on descegy.bibalex.org ( requires Macromedia Flash)

- Description de l'Egypte. on gallica.bnf

- Digital copies of Heidelberg University Library , 18 volumes

- Numerous blackboards and sheets, including a number of maps , reproduced on description-egypte.org

- Volume 1, 1st edition, 1809 ( digitized on archive.org ).

- Volume 1, 1st edition, 1809 ( digitized on google books ).

- Description of the work, on travellersinegypt.org (English).

credentials

- ↑ Un monument éditorial, la Description de l'Égypte, website of the École Normale Supérieure, accessed on March 7, 2017 (French)

- ↑ Christelle di Pietro: Premier bilan de l'incendie de l'Institut d'Egypte au Caire ( Memento of March 4, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Reported on the website of the École Nationale Supérieure des Sciences de l'Information et des Bibliothèques (ENSSIB ) at the University of Lyon on December 22, 2011, accessed on March 7, 2017 (French)

- ↑ Minister: Egypt still has 3 copies of Napoleon's 'Déscription de l'Egypte', in: Egypt Independent of December 19, 2011, accessed on March 7, 2017 (English)

- ↑ Javier Sierra: El libro tesoro de Napoleón escondido en España, in: El Mundo of May 3, 2015, accessed on March 7, 2017 (Spanish)