Edward John Eyre

Edward John Eyre (born August 5, 1815 in Whipsnade , Bedfordshire , or Hornsea , Yorkshire , † November 30, 1901 in Walreddon Manor in Devon ) was a British explorer in Australia and politician. He became known for his expeditions north of Adelaide and his journey along the Australian south coast, as well as for his role as governor of Jamaica during the Morant Bay Uprising .

According to him, in South Australia of Lake Eyre , the Eyre Peninsula , the Eyre Creek and the Eyre Highway named, also to New Zealand the villages Eyreton and West Eyreton in the region Canterbury , and the Eyre Creek .

Childhood and Adolescence in England

Edward John Eyre was born on August 5, 1815, the third son of Sarah and Anthony William Eyre. The exact place of birth of Edward John Eyre is unknown. In the first biographies of Edward John Eyre, namely those of Hamilton Hume , Malcolm Uren and Robert Stephens , information about his date of birth can be found, but not the place of birth. Still, the Dictionary of National Biography indicates Hornsea in Yorkshire . But since he was baptized on August 17, 1815 in Whipsnade , Bedfordshire and his father worked there as a curator, it is likely that Eyre was also born in Whipsnade. Only later did the family move to Hornsea, where their father became vicar of Hornsea and Long Riston. Eyre comes from an educated family: one grandfather had a doctorate , the other canon in York and his wife was also the child of a priest.

Little is known about his childhood, but it can be said that Eyre enjoyed moving around outside, using his hands, and developing great determination and stubbornness. In return, he was a mediocre student whom his father sent to several schools in Thorparch , Rotherham , Grantham , Louth, and Sedbergh . When he was 16, he left Sedbergh school to join the army. However, his father persuaded him to go to Australia. Although Eyre knew nothing about Australia, he agreed, because he believed he could lead an independent and self-determined life there. At the age of 17, on October 19, 1832, he left for Australia with Ellen .

Australia

On March 2, 1833, his ship entered Hobart . Eyre enjoyed the stay there; he used the time for horse riding and hunting and also got to know William Broughton , who was Archdean of New South Wales at the time and later Bishop of Sydney . This meeting was the beginning of their long friendship. In Sydney, where he arrived on March 28th, he initially rented an Australian Hotel and began looking for work, but initially found nothing. His encounter with an old colonist, to whom he was supposed to deliver a letter, was formative for him. The latter advised him not to rely on the government, but to move into the wilderness and raise cattle. Nevertheless, he initially stayed in Sydney, was unemployed and was forced to sell some of his equipment. The situation changed when he was invited to his station on the Hunter River by Henry Dumaresq , a colonel in the British Army . After a three-day and arduous journey, Eyre was finally at Dumaresq 'Farm St. Helier’s on May 13th . Eyre was impressed with the standard of living of the Dumaresq family in the bush, and Henry Dumaresq placed Eyre on a farm 25 miles away run by a skilled colonist, William Bell. Eyre should first gain experience there before venturing into his own company. A few days later, Eyre returned to Sydney to pack his things and take convicts to work. It was not until June 21 that he left Sydney with a team of oxen and a driver.

In July he bought a flock of 400 sheep. In 1834 he bought 510 hectares of land in the Molonglo Plain near Queanbeyan . In 1835 he and Robert Campbell drove 3,000 sheep from the Liverpool Plains to the Molonglo Plains. After problems with sick sheep, however, he sold his land again and returned to Sydney in 1837, where he first met Charles Sturt . By the end of March 1837 he bought 78 cattle, 414 sheep and a few oxen and horses, which he wanted to drive south and sell in Melbourne. He used his former property in the Molonglo plain (Woodlands) as a collection point, from where he left on April 1st. Edward John Eyre arrived in Melbourne on August 2nd of that year and sold the cattle for a profit.

Expeditions

Overland expeditions to Adelaide

Back in Sydney, he wanted to be the first to travel overland to the colony of South Australia founded in 1836 . So he put together an expedition and bought 300 cattle, which he wanted to drive from the Limestone Plains to Adelaide. He set out on January 3, 1839, and a little later on January 15, his foreman John Baxter joined him. After a short stay in Adelaide he went back to Sydney and this time bought 1,000 cattle and 600 sheep, which he drove to Adelaide and sold there.

Expeditions of 1839

With the £ 2,000 profit he had left, he bought a plot of land in Adelaide to farm. It did not last long there, however, because in May 1839 he led an expedition to the north. He advanced into the Flinders Range from the northern tip of the Spencer Gulf in search of fertile pastureland . He also sighted Lake Torrens , but it was a dry salt lake at this time of year. Eyre returned to Adelaide without success, but in August he led an expedition on the Eyre Peninsula . On August 5, 1839, he took a ship to Port Lincoln on the southern tip of the peninsula and followed the west coast to Streaky Bay , where he changed direction and now more or less directly across the Gawler Ranges and south to Lake Torrens Moved east and returned to Adelaide over the tip of the Spencer Gulf.

Expedition in Western Australia

In January Eyre took two other people and sheep and cattle to King George Sound and drove the herd of cattle to the Swan River Colony , today's Perth . On the way back he brought Wylie with him to Adelaide. The Aborigine accompanied Eyre as a friend on his later expeditions.

Expedition from 1840 to 1841

During Eyre's absence, a committee had been set up in Adelaide to organize an expedition along the west coast. Eyre heard about it and applied to lead the expedition, but managed to get the expedition to explore the lakes in the north again. The group was put together within a few weeks and consisted of five other men in addition to Eyre, including John Baxter. They took 13 horses, 40 sheep and food with them for an initial three months. Further provisions were brought by ship to the northern tip of the Spencer Gulf. From Mount Arden he made his way north through the Flinders Ranges. With several advances he was able to reach Lake Torrens in the west, the southern tip of Lake Eyre in the north and Mount Hopeless in the east. Eyre was disappointed with the results of this trip, but still determined to finally find fertile land. His plan was to look further west and ultimately carry out the expedition that the committee originally intended.

Baxter was sent to Streaky Bay with two whites and one Aboriginal, while Eyre himself went with the rest of the force to Port Lincoln on the southern tip of the Eyre Peninsula. From there he sent one of his men to Adelaide with a request for more provisions. He was also supposed to pick up Wylie from Adelaide.

On November 3rd, Eyres and Baxter's groups met at Streaky Bay, from where they moved to Fowler's Bay to set up camp. It was only on the third attempt that the group managed to reach the top of this bay. In view of the considerable difficulties the group had up to then, Eyre preferred to send the other participants back except for Baxter, Wylie and two other Aborigines. On February 25, 1841, he and the rest of his troop began the 1,300-mile journey to King George Sound. The journey was very hard, they moved through the desert and only encountered good water for the first time after 217 kilometers on March 12 at today's Eucla . They had to struggle with the unfavorable terrain and the lack of water in the Australian summer during the entire trip.

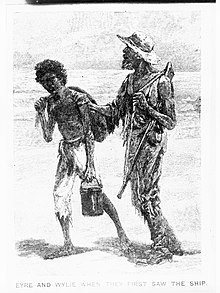

However, on April 29, the two Aborigines murdered Baxter and fled with some of the supplies and all working firearms. Wylie and Edward John Eyre continued on the trail for over a month until they discovered a French whaler at Esperance on June 2 and took them in for the next few days. Eyre insisted on continuing his voyage as far as Albany and was supplied with provisions by the ship's captain, Rossiter. In his honor, Eyre named the bay Rossiter Bay . On July 7th, Eyre finally reached Albany. For this expedition he was awarded the “Founder's gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society” in 1847 .

Protector of Aborigines

On the way back from Albany Eyre wrote a petition to the Governor of South Australia, in which he asked to lead an expedition from Moreton Bay (the bay of today's Brisbane ) to Port Essington in today's Northern Territory . This he was denied, instead he was assigned an administrative position: as Resident magistrate and Protector of Aborigines , he was responsible for dealing with the local Aborigines in Moorundie on the Murray River from October 1841. Previously, there had been repeated clashes between the local population and passing cattle drovers. During his tenure, the number of attacks and violent clashes had decreased noticeably, although the settlement by European immigrants increased sharply.

England, New Zealand and West Indies

In December 1844 Eyre returned to England. He took two young Aborigines with him, who were to be trained and educated there at his own expense. In 1846 he became Lieutenant Governor of New Zealand , but fell out with Governor George Gray and returned to England in 1853. To compensate, he became lieutenant governor of St. Vincent in the Caribbean in 1854 . 1860 he was appointed as acting governor of the Leeward Islands were added. There he proved himself and therefore came to Jamaica in 1861 as acting governor , where he was promoted to Governor-in-chief in 1864 .

Morant Bay Riot

When the Morant Bay Uprising began on October 11, 1865 , Eyre considered this to be the start of a major revolt and imposed martial law on Jamaica, with the exception of the capital Kingston . By the end of the war on November 13th, the use of the army resulted in 608 deaths, 600 flogging and over 1000 burned down homes. Eyre also had an African-born member of the legislature, George William Gordon , arrested in Kingston (where martial law did not apply) because he and many others viewed William Gordon as the instigator of the uprising. Gordon was then removed from Kingston to be sentenced to death by a court-martial.

The governor's actions were welcomed in Jamaica, but sharply condemned in England, with Eyre being described as a murderer. A royal commission concluded that Eyre had reacted quickly but inappropriately harshly to the uprising, so that he was removed from office and ordered back to England. There was still arguments about his role as governor, a total of three complaints against Eyre, but rejected each time.

Last years and death

In 1874 Eyre officially retired and he moved to Walreddon Manor near Tavistock , where he died on November 30, 1901. His wife and five children survived. In 1901 the Royal Society of New South Wales awarded him the Clarke Medal .

Works

He reported on his travels in Australia in his

- Journal of expeditions of discovery into Central Australia and overland from Adelaide to King George's Sound in the years 1840-1: Sent by the colonists of South Australia, with the sanction and support of the Government: including an account of the manners and customs of the Aborigines and the state of their relations with Europeans. T&W Boone, London 1845 online

- An account of the manners and customs of the Aborigines and the state of their relations with Europeans online , accessed December 8, 2010

literature

- Michael Wordsworth Standish: Eyre, Edward John . In: Alexander Hare McLintock (Ed.): An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand . Wellington 1966 ( online [accessed December 15, 2015]).

- Geoffrey Dutton: The Hero as Murderer. The life of Edward John Eyre, Australian Explorer and Governor of Jamaica 1815–1901 Collins / Cheshire, Sydney 1967.

- Hamilton Hume: The Life of Edward John Eyre. In: The Times. 3rd and 5th December 1901

- Sydney Haldane Olivier : The Myth of Governor Eyre . - Leonard & Virginia Woolf, Hogarth Press, London 1933

- William Law Mathieson: The Sugar Colonies and Governor Eyre, 1849-1856 . Longmans, London 1936

- Eyre, Edward John (1815-1901). In: Perceval Serle (Ed.): Dictionary of Australian Biography . Angus and Robertson, 1949 online at gutenberg.net.au (English)

- Gad Heuman: Eyre, Edward John (1815-1901). In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), as of January 2008

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. P. 402.

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. P. 16.

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. P. 17.

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. P. 18.

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. P. 19.

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. Pp. 20, 21.

- ↑ Dutton: Hero as Murderer. P. 21.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Geoffrey Dutton: Eyre, Edward John (1815–1901) . In: Douglas Pike (Ed.): Australian Dictionary of Biography . Volume 1. Melbourne University Press, Carlton (Victoria) 1966. 2nd revised edition 1977, ISBN 0-522-84121-X (English).

Remarks

- ↑ At that time it was customary to bring prisoners from England to Australia and use them there for work. Any settler could apply for prisoners to be assigned to him.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Eyre, Edward John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 5, 1815 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Whipsnade , Bedfordshire |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 30, 1901 |

| Place of death | Walreddon Manor, Devon |