Eilean Donan Castle

| Eilean Donan Castle | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Eilean Donan Castle in Loch Duich |

||

| Creation time : | around 1220 | |

| Castle type : | Niederungsburg | |

| Conservation status: | restored or reconstructed | |

| Place: | Dornie | |

| Geographical location | 57 ° 16 '26.5 " N , 5 ° 30' 58" W | |

|

|

||

Eilean Donan Castle ( Scottish Gaelic : Eilean Donnain ) is a lowland castle near Dornie , a small village in Scotland . The name itself means "Donan's Island" and refers to St. Donnán von Eigg, a Celtic martyr from the 6th century. Eilean Donan Castle is located on Loch Duich in the western Scottish Highlands . The castle is located on a small headland that turns into a tiny tidal island at high tide . It can then only be reached via a stone pedestrian bridge. The castle is the ancestral home of the Scottish clans of Macrae .

history

Archaeological finds of slag that can not be precisely dated prove that the island was settled in the late Iron Age or early medieval period. A small monastery built on the island and attributed to St. Donnán von Eigg († 617) has not yet been proven by finds.

The origins of the castle

The construction of the castle began around 1220 during the reign of Alexander II as a defense against Viking raids. The castle wall (no longer preserved today) and the residential tower originated from this time. Contradicting documents from this period give the Earl of Ross and the clans Mackenzies of Kintail , Macrae and Maclennan as lords of the castle; the clan Mackenzies of Kintail is occupied from 1266.

In the winter of 1307/08, Eilean Donan Castle served Robert the Bruce as a refuge when he was on the run from the English during the First Scottish War of Independence . The support he received from the Clan Mackenzies of Kintail, however, was rather low.

The Macrae clan settled in the Eilean Donan Castle area from the early 14th century .

Turbulent years

To pacify the rebellious Highlands, King James I traveled to Inverness in 1427 . He invited all Clan Chiefs to do so under the assurance of safe conduct, but had them either imprisoned or executed immediately upon their arrival. Among the Clan Chiefs was the young Alexander Mackenzie, nominally the 6th Chief of Kintail. He was convicted of attending school in Perth as a punishment. During his absence, Eilean Donan Castle was held by Duncan Macaulay, in the interests of Alexander and against the opposition of various relatives of the Mackenzie clan. In his active time as Clan Chief, Alexander supported the monarchy, also against the Lords of the Isles of Clan MacDonald . For this he was confirmed in his position by the king in 1463.

Unlawful acts by Hector Roy Mackenzie led to the ostracism of Clan Mackenzie as rebels in 1497. In 1503 the Earl of Huntly agreed to conquer Eilean Donan Castle, hand it over to the Crown and keep it occupied in their interests. Jacob IV provided a ship for this purpose. The castle was cleared and handed over after a short siege.

In a deed from 1509, John of Killin was awarded the territory of Kintail and Eilean Donan Castle. In 1511 Christopher Macrae was appointed keeper of the castle.

In 1539 the castle was attacked by Donald Gorm Macdonald of Sleat. Although defended by only three people, the attack was repulsed after the accidental killing of Donald Gorm Macdonald.

In 1580 a feud began between Clan Mackenzie and Clan MacDonalds of Glengarry. In the following years, Eilean Donan Castle became the basis and target of this dispute, which only ended in 1602 with the death of Angus MacDonald of Glengarry.

Farquhar Macrae was born at the castle in 1580. After studying in Edinburgh and being ordained a priest, he was appointed administrator of the castle in 1618. Colin Mackenzie of Kintail , Earl of Seaforth from 1623 , visited the castle regularly. He was entertained by the administrator with his entourage (about 300 to 500 men) and the neighboring lairds. In 1635, George Mackenzie, 2nd Earl of Seaforth, appointed Farquhar Macrae as tutor to his six-year-old son, Kenneth, who was then educated at Eilean Donan Castle.

During the English Civil Wars of the mid-17th century, the Earl of Seaforth sided with Charles I. After the king's execution in 1649, the Parliament of Scotland ordered an occupation of Eilean Donan Castle. However, the occupiers were not welcome and were forced to withdraw due to popular resistance.

The following year, Simon Mackenzie of Lochslin, brother of the Earl of Seaforth, gathered troops around Eilean Donan Castle to support the royalist cause. However, he fell out with Farquhar Macrae, which in turn caused him to vacate the castle. Farquhar was the last caretaker who lived at the castle until the restoration of Eilean Donan Castle.

After that, the castle was briefly occupied by the Earl of Balcarres, who at the time supported the royalist Glencairn uprising . In June 1654 General Monck, the military governor of Oliver Cromwell in Scotland, marched during the suppression of the uprising by Kintail.

Destruction in the First Jacobite Rising

In April 1719, 300 soldiers under the command of George Keith, 9th Earl Marischal , landed at Loch Duich and occupied Eilean Donan Castle as part of the Spanish support for the Jacobites . However, because the promised main support from Spain failed to materialize, the expected uprising of the Jacobite Highlanders did not take place. The Royal Navy then sent three frigates to the region, which reached the castle on May 10th. The Spanish soldiers shot muskets at the negotiator who was approaching in a dinghy; then the frigates opened fire on the castle. The bombardment lasted a day and a half until a crew from the frigates stormed the castle and captured the 44 survivors. The supplies found contained over 300 barrels of gunpowder which were then used to blow up Eilean Donan Castle.

The restoration

In 1912 Lt. Col. John MacRae-Gilstrap removed the ruins and began the first restoration work. He was supported by a resident stonemason, Farquhar MacRae, who shared the dream with MacRae-Gilstrap: "claimed to have had a dream in which he saw, in the most vivid detail, exactly the way the castle originally looked". The complete restoration was carried out between 1920 and 1932, deviating from the original plans, the stone access bridge and a war memorial for the soldiers of the Macrae clan who died in World War I were also created. The cost of the restoration is now estimated at £ 250,000.

After MacRae-Gilstrap's death in 1937, the castle remained uninhabited and opened to the public as a museum in 1955.

Eilean Donan Castle today

Eilean Donan Castle is now owned by the Conchra Foundation created by the Clan Macrae and is used as a museum. It is conveniently located for tourists directly on the A87 on the way from Glasgow to Kyle of Lochalsh and the Isle of Skye and is one of the most photographed subjects in Scotland. In 2009, well over 310,000 visitors were counted, making Eilean Donan Castle the third most visited castle in Scotland.

Construction phases

Early attachment

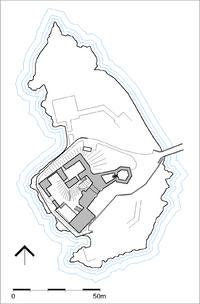

In the 13th century a curtain wall was built that covered most of the area of the island above the flood line. The enclosed area was approximately 3000 m². Remains of this wall can still be found in the northern part of the island, other parts were built over by later extensions of the castle. In the northern part of the wall there are foundations of a keep of about 12 * 13 m, and the remains of the foundations indicate two further defense towers on both the northeast and southwest corners of the curtain wall. Nothing is known about the original height of these towers. Access to the facility was probably via a lake-side gate in the northwest of the curtain wall; in the southwest, another access is conceivable on a small beach.

In the 14th century, a tower house was built on the highest point of the island, leaning against the curtain wall. The tower measured 16.5 * 12.4 m and had 3 m thick walls. The vaulted ground floor was divided into two rooms and had a staircase to the north that gave access to the (probably two) floors above.

Archaeological excavations in 2008 and 2009 confirmed much of these assumptions and found evidence that metalworking also took place in the northern part of the castle.

The reduced castle

Probably in the late 14th or early 15th century, the curtain wall was abandoned in favor of a smaller defensive structure. This now only enclosed about 25 meters square, the entrance was in the east. The reasons for this change are unknown.

Two buildings were added during the 16th century. A small house was built in the southeast corner of the new curtain wall. It had access to the battlement via a spiral staircase and probably served as an apartment for the castle administrator. An L-shaped building was added in the south-west corner of the curtain wall, but possibly not until the beginning of the 17th century. The southern part of the building is outside the curtain wall, but the northern wing (possibly as a later addition) inside.

The hornwork

With the increasing importance of cannons in warfare, the castle was expanded in the late 16th century to include a bastion or hornwork facing east . This consisted of an irregular hexagonal structure with a maximum size of 11.5 m. This hornwork was connected to the eastern part of the castle by a triangular courtyard enclosed by walls. Inside the hexagonal structure was a well over 10 m deep and about 5 m in diameter.

After its completion, the hornwork served as an entrance to the castle. The well was covered with a movable bridge and thus formed a further defense. In the course of the 17th century this easily defensible access was given up in favor of a more conveniently located and more convenient entrance in the south wall.

Drawings by Lewis Petit from 1714 showed that the castle was largely destroyed; only the house in the southeast corner still had a roof. Four years later it was completely demolished.

The reconstructed castle

The current castle buildings are the result of reconstruction at the beginning of the 20th century. Although the reconstruction followed the existing layout, the details of the current castle differ from its original exterior. Lewis Petit's drawings were only found shortly before the restoration was completed, so plans by MacGibbon and Ross from the 19th century were used as a guide.

The castle is entered today from the south through a portal that can be secured with a portcullis. Above the portal is the coat of arms of John Macrae-Gilstrap and a Gaelic inscription “Cho fad 'sa bhios MacRath a-stigh cha bhi Frisealach a-muigh.” The translation is: “As long as there is a Macrae inside, there is none Fraser outside ”. Through the portal you enter the courtyard, the level of which has been lowered to be level with the entrance to the tower house.

The current buildings in the southeast reflect the shape of the earlier structures, including the circular stair tower, but are larger in size. A small tower was also built in the northwest corner of the curtain wall. In the southwest, only the southern part of the L-shaped building was rebuilt as a simple three-story house, while the square of the northern part serves as an open platform with a view over Loch Duich.

The division of the house follows the original dimensions, although the ground floor, which was previously divided, now only contains one room: the billeting room with barrel vaults . The first floor houses the dining room decorated with coats of arms with an oak ceiling and a fireplace in the style of the 15th century.

Trivia

The castle has often been used as a backdrop for films and television series; including in an episode of the television series Das Blaue Palais by Rainer Erler and in films such as Highlander - There can only be one , Elizabeth - The golden kingdom , Braveheart , Prince Iron Heart , Tempting Trap , In love with the bride and Rob Roy . For the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough , some scenes were shot on location.

literature

- James Brichan et al. a .: Origines Parochiales Scotiae. the Antiquities Ecclesiastical and Territorial of the Parishes of Scotland . WH Lizars, Edinburgh 1855 ( online at archive.org [accessed January 15, 2015]).

- David Hugh Farmer: The Oxford Dictionary of Saints . University Press, Oxford 1992, ISBN 0-19-283069-4 .

- Alexander Mackenzie: History of the Mackenzies . A. & W. Mackenzie, Inverness 1894 ( online at archive.org [accessed January 15, 2015]).

- John MacRae: Eilean Donan Castle . Dixon, Newport (Wight) 1978.

- Roger Miket, David L. Roberts: The Medieval Castles of Skye and Lochalsh . Birlinn, Edinburgh 2007, ISBN 978-1-84158-613-7 .

- Paula Milburn: Discovery and Excavation in Scotland . Archeology Scotland, Vol. 9. University of York, Archeology Data Service, 2008, ISSN 0419-411X ( Online (PDF; 16.5 MB) [accessed January 15, 2015]).

- Paula Milburn: Discovery and Excavation in Scotland . Archeology Scotland, Vol. 10. University of York, Archeology Data Service, 2009, ISSN 0419-411X ( Online (PDF; 21.1 MB) [accessed January 15, 2015]).

Web links

- Eilean Donan Castle as a 3D model in SketchUp's 3D warehouse

- Welcome to Eilean Donan Castle. Eilean Donan Castle, accessed January 15, 2015 .

- Eilean Donan Castle on the road to Skye, Scotland. Camvista.com, accessed January 15, 2015 (English, webcam).

Individual evidence

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Saints , p. 135

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 83f.

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 87.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1894 , p. 47ff.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1894 , p. 74

- ↑ Brichan 1855 , p. 394

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , p. 22ff.

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , p. 28

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , pp. 40ff.

- ↑ Macrae 1910, pp. 58ff.

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , pp. 195f.

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , p. 61ff.

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , p. 65

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , p. 70

- ↑ Macrae 1910 , pp. 63f., 354

- ↑ Ships' Logs 1719: Hms Worcester and Hms Flamborough. Clan Macrae, 2013, accessed January 15, 2015 .

- ^ Marigold MacRae: Historic Places: Eilean Donan. (No longer available online.) Clan Macrae Society of North America, 2013, archived from the original on May 11, 2002 ; accessed on January 15, 2015 .

- ↑ Timeline. Eilean Donan Castle, 2013, accessed January 15, 2015 .

- ↑ Marina Martinolli, Claire Bereziat: The 2009 Visitor Attraction Monitor. (No longer available online.) VisitScotland, archived from the original on April 21, 2014 ; accessed on January 15, 2015 (English, PDF; 1.3 MB; p. 79).

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , pp. 95f.

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 100ff.

- ↑ Milburn; 2008 , p. 110

- ↑ Milburn; 2009 , p. 104

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 107

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 103f.

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 105f.

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 109

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 100

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 110

- ↑ Miket; Roberts; 2007 , p. 105f.