Scottish clan

A Scottish clan is a traditional large social association of people in Scotland who are generally at least distantly related . The English word clan (from Scottish Gaelic clann "children, descendants, tribe, family") originally referred to a group of families who inhabited a narrowly defined geographical unit, for example a mountain valley (glen) or an island, and which were located on one proclaimed common descent and origin from an ancestor (mostly of mythical or legendary origin). They all recognized the clan chief as their lord and judge, in return he was obliged to defend the interests of his followers with a weapon. Today the state Lord Lyon King of Arms watches over the rights of clan chiefs, clans and families.

The Scottish clans have their origins in the north-west of Europe . Scotland consists of the northern part of the largest European island Great Britain and several archipelagos. Until 1707 it was the independent Kingdom of Scotland , then it was united with the Kingdom of England , with which it had been ruled in personal union since 1603 .

Inner structure of a Scottish clan

Chief

The head of a clan is the chief . This office, combined with the titles, was passed on to the oldest male descendants . The chief was the chief judge in disputes within the clan and its chief military leader . He distributed the land that originally belonged to the clan as a whole, but was seen as the chief's land with the advent of the royal feudal system , and was responsible for the poorest members of the clan.

Today the title of chief is a legal asset guarded by Scottish law and the Lord Lyon King of Arms . The Chief is the owner of the rights, such as a clan badge ( badge ) and a special weave pattern for fabrics ( tartan ) . For example, he is free to regulate the wearing of a tartan. As a sign of his dignity, the clan chief wears three feathers on his tartan cap ( bonnet ) .

Chieftain

The chieftain is the head of an important family within a clan. He used to settle disputes within his family and was responsible for serving his family to the clan chief. He led his family's warriors in combat. The chieftain of the oldest family unit within the clan commanded the right flank in the war. Today, many chieftains, like the chiefs of their clan, hold the rights to coats of arms, tartans, badges, etc. As a token of their dignity, the chieftain wears two feathers on the bonnet.

bard

Every chief and every major chieftain had a bard at his court who was the chief's narrator and entertainer in peacetime. He wrote poems on special occasions, such as B. Weddings, births, etc. In times of war he got the clan in the mood for the fight, in which, among other things, he presented the glorious history of the respective clan.

Piper

Like the bard, the office of piper was divided into two parts. Responsible for entertainment at festivals in peacetime and gathering point for own troops in wartime. Often times, one person held the post of bard and piper at the same time.

Structure of the Scottish Clans

A distinction is made between three categories of clans:

- The most important group includes clans such as the Stewart of Appin, Campbells , the MacDonalds , the MacLeods , the Gordons and perhaps even Clan Chattan and the MacKenzies , who ruled over large areas. They all smashed smaller clans or took over these and their lands with power, through marriage or skillful political action. In addition, they often had great political influence at the national level.

- The second category with a little less influence were the McGregors, Frasers , Gunns , MacPhersons, MacLachlans , and MacLeans . This also included small family groups such as the Kennedy clan.

- Finally, there were clans that had titles or names such as "Clan of the Night" (the Morrisons of Mull), "Clan of the British" (the Galbraith family of Gigha) or the "Clan of the children of Raigns" (the Rankins).

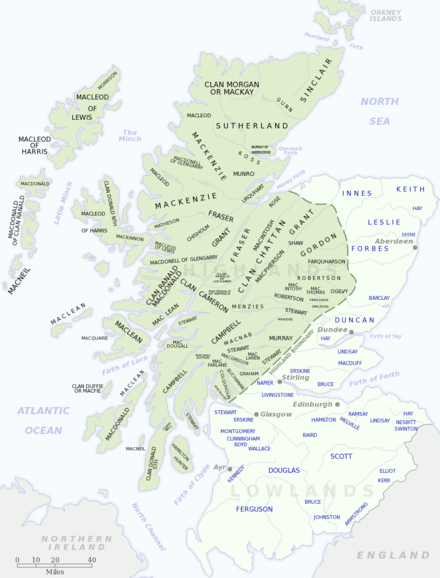

Geography of the clans

In general, the clans are connected to the highlands and the islands and only to a lesser extent are native to the peripheral areas such as the Borders and Galloway . In the central area of Scotland and in most of the plains , such kin groups were displaced very early by the feudal system . However, there were also some clans in other regions.

With Margaret, the wife of Malcolm Canmore , and especially her son David , feudal law, which is the exact opposite of clanism, found its way into Celtic Scotland. Originally the land belonged to the clan community and was administered by the chief; but under feudal law the whole country became royal property.

The clan's loyalty traditionally belonged to their chief; they did not see themselves as direct subordinates of the king. The determination of a number of kings to replace this clan system with feudalism drove a wedge between the Celtic highlands and the Anglo-Saxon lowlands, which remained stuck until the turn of Culloden , which marked the end of the Jacobite uprisings .

History and Decline of the Scottish Clans

The clans' feeling of togetherness was primarily created by the Wars of Independence (1296–1314). The 21 clans that gathered around Robert the Bruce on the battlefield of Bannockburn had a common goal: the freedom of the Scottish people from any foreign rule. But the winners could also be sure of the generous distribution of lands and titles; the vanquished were driven out.

Most of the clans had established themselves by the end of the 14th century. The clan chiefs lived Sometimes very princely on handsome fortresses . Like feudal lords, they leased lands to their subordinates. Belonging to a clan did not only mean to be integrated into a social network, but also included the obligation to do military service for the master.

This social fabric revealed its weak points when the clans began to form their own administrative structures. Smaller families sought protection from their powerful neighbors through alliances and counter-alliances. For a wide variety of reasons, there were clashes from minor feuds to bloody battles - yes, real clan wars that sometimes lasted for decades.

When Scotland and England had long been united under one crown and the Lowlands pacified, the clans were still entrenched in the impassable bulwark of the highlands . Given the geography of the Scottish Highlands, it is no wonder the kings found it very difficult to exercise their authority over the people who lived in the remote and inaccessible mountains. The highland line extends diagonally from the Clyde to Stonehaven on the North Sea, south of Aberdeen . To the north of it, the clans felt bound to the respective areas that they claimed as family land. The deep valleys and wide highlands were populated by clans such as the Campbells in Argyll , the Camerons in Lochaber , the Robertsons in Rannoch , the Mackays in Sutherland and the islands to the west were the domain of the MacDonalds in Islay , the Macleans in Mull , Tiree and Coll , while Skye was split between the MacDonalds, MacLeods, and Mackinnons.

Despite the barren soil, all clans were almost self-sufficient and lived on the small cattle that grazed in the mountains. The clan members fished on the islands and on the coast and exported the surplus catch to the lowlands. In the valleys they had their barley for brewing whiskey (mainly for the edification of the chief and his immediate subordinates) and oats as a staple food. It was a meager life for the members of the clan. Because the cattle had to be protected, these Celtic mountain people developed perseverance and gained martial experience. On suitable occasions, the Lowlanders and the British were equally appalled by their fury.

12th Century

The first prominent figure named in clan history was Somerled , the ancestor of Clan Donald. He was the leader in the resistance against the Norwegians, who controlled the Western Isles , Orkney and Shetland Islands . Somerled was an exceptional warrior of Pictish Norwegian descent. After a terrible naval battle in 1156, he won the Kingdom of Man . He controlled the western islands from Bute in the Clyde to Ardnamurchan .

In return for Somerled's promise of loyalty, King Malcolm IV recognized his rule there. In this context, however, there was a significant misunderstanding for the first time. While Malcolm thought that Somerled received his lands as a fiefdom from the Crown, the latter regarded himself as a conqueror and an autonomous ruler.

Somerled had three children from his politically adventurous marriage to Ranghildis, daughter of the Norwegian King of the Isle of Man, two of whom continued his line. Dougall, who founded the MacDougalls of Argyll and Lorn, and Reginald, whose son was named Donald, the MacDonalds of Islay. These descendants of Somerleds - the MacDonalds - became the " Lords of the Isles ".

13th Century

The clans didn't work together. Even after the end of the Norwegian occupation in 1266, they fought against each other in the highlands, and the crown desperate to secure its loyalty and pacify the highlands.

A prime example was the MacDougalls by Lorne and MacDonalds by Islay. They opposed King Robert the Bruce . John Comyn , murdered by Robert's companion, Roger de Kirkpatrick , had been related to them.

Nevertheless, Clan Donald followed the chief's brother - Angus Og - and fought on Bruce's right side in the Battle of Bannockburn . This act of loyalty to the flag strengthened the MacDonald's position and saved the disloyal members of the clan from punitive action. Splintering and falling out, of which there are countless examples and reports, were the rule within the clan groupings.

15th and 16th centuries

James IV finally managed to finally enforce the Norman feudal concept of the lowlands in the highlands as well. For many chiefs, he confirmed their land claims with a royal parchment - the so-called sheepskin deed.

He thereby emphasized that these vassal clans received their lands directly through the crown. James also gave Campbell of Argyll a three year contract over several lands previously ruled by the Lords of the Isles. The Campbells wisely supported anyone who gave them advantages. In addition, they began to dominate the adjacent lands as well.

In Argyll and the northwest, they took every opportunity to expand their land holdings - the fate of the MacGregors is an eloquent example.

17th and 18th centuries

The MacGregors (a later descendant known as Rob Roy, whose name is likely derived from the Scottish Gaelic "Raibert Ruaidh", Robert the Red) owned ancient clan land in both Argyll and Perthshire .

Without documentary proof of ownership and without this sheepskin certificate, they could only refer to tradition. With the seizure of more and more MacGregor land, this clan gradually despaired - and in order to be able to survive at all, the MacGregors became cattle thieves.

After 1603 the Campbells were determined to put an end to them for good. The Earl of Argyll , chief of Clan Campbell, stirred up a dispute between the MacGregors and the Colquhouns of Luss on Loch Lomond . This dispute, like many others, ended in a terrible battle that took place in Glen Truim . Although the MacGregors won despite the overwhelming power of their opponents, it was a Pyrrhic victory . The battle was so bloody and terrible that James VI. , just also crowned James I of England, had a law passed through his Privy Council, which made the MacGregors outlaws and should erase their name.

After that, this clan was an outlaw clan for 139 years (in between the order was temporarily lifted). Nevertheless, in 1775 - 30 years after the Battle of Culloden - 826 people still admitted to membership in the MacGregor clan, thereby demonstrating the remarkable traditional emotional bond that the old clan principle created.

James was tired of always hearing about blood feuds and arguments. So he finally commissioned Lord Ochiltree to bring law and order to the islands under all circumstances. This man was assisted in his difficult task by Andrew Knox , the Bishop of the Isles.

The chiefs of the MacLean of Duart , Donald Gorm of Sleat (Skye), Clanranald, MacLeod and Maclean of Ardgour were obviously not in a hurry and together they first dined at Duart Castle (Mull) before accepting the invitation to the sermon followed by Bishop Knox on the flagship Lord Ochiltrees. Once on board, the ship lifted anchor and took them to Edinburgh , where they were imprisoned and not released until they agreed to help Bishop Knox reform the islands.

At the end of the 17th century Britain gradually turned to a new commercially prosperous era with no more room for clans. At least that was William III's point of view . who had cemented his power with the Battle of the Boyne .

He decided that something more drastic had to be done with the Highlands, since they were obviously still on the side of the Stuart dynasty. The Scottish Sir John Dalrymple , Earl of Stair, Undersecretary of State for Scotland, planned a solution to the highlands problem. He was supported in his endeavors by William and found a willing helper in John Campbell , the Earl of Breadalbane.

Initially, Campbell received £ 12,000 from the king. With that he was supposed to buy the loyalty of the clan bosses. This of King William III. Secretary of State appointed for Scotland and responsible for it, however, announced in a confidential conversation to Campbell that the Donnel and Lochiel clans should be exterminated.

So it was decided that all chiefs had to take an oath of loyalty to the king by January 1, 1692. Those who opposed, would "be met with fire and sword and all kinds of hostilities" . The date had obviously been chosen very carefully, because the harsh highland winter would partially paralyze the highlands. A point that Stair had calculated very well:

- “Winter is the only season in which we can be sure that the clan members will not be able to escape to the mountains with their wives, children and cattle. This is the right time to destroy them in the long, dark night ”.

Most clan chiefs swore this oath immediately. Only the mighty MacDonnel of Glengarry and old MacIan MacDonald of Glencoe hadn't done this by January 1st. After much deliberation, MacIan tried to take his oath of allegiance on December 31st in Fort William . But since the magistrate was not present, he was forced to move through the snow to Inveraray . That terrible winter, MacIan didn't arrive in Inveraray until January 2nd. Since there was only one deputy to the commandant, his oath did not reach Edinburgh until January 6th.

Wilhelm finally had his scapegoat. Dalrymple wrote to the commandant at Fort William:

- "If MacIan of Glencoe and his tribe behave so differently from the rest, we have a clear justification in public justice for this thieving clan to be exterminated with stem and stem."

120 men from the Regiment of the Earl of Argyll were marched to Glen Coe under the command of Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon to take up quarters in the huts. The soldiers were received with the usual highland hospitality. The MacDonalds shared the meager food and drink with them for over 15 days. Captain Campbell even played cards with old MacIan MacDonald and his sons.

But on February 12, 1693 the captain received the order:

- “You are hereby ordered to attack the rebels, the MacDonalds of Glencoe, and bring everyone under 70 to the sword. You have to make sure that the old fox and his sons cannot escape your hands under any circumstances ”.

The killing was due to begin at five the following morning. The evening before, Captain Campbell is said to have played cards with MacDonald's sons, as he had done in the previous days, and also mentioned how much he was looking forward to dinner the following day with the Chief. When morning approached after a long and stormy night, the soldiers began their cruel task. The result was that more than 30 MacDonalds were murdered. Many members of the clan who had managed to escape the still raging blizzard froze to death in it. But quite a few survived and made the slaughter known. Not only was it an utterly pointless crime, but also a total and deliberate mockery of the centuries-old highland tradition that offered hospitality to even the worst enemy.

Jacobite uprisings

Wilhelm may have demonstrated his power and determination, but achieved the exact opposite of what was intended. After Glencoe, the Stuarts looked more auspicious than ever. Shortly after the parliamentary unification of Scotland and England, it was clear to the clans that they only had minority status in North Britain , as Scotland was now mostly called on the English side. They turned their hopes more and more to "the king across the water", James, and after his death on his son Francis Edward, the Old Pretender .

In 1714 George I came to the throne of the United Kingdom. He was unattractive, poorly intellectually endowed, and had little knowledge of his new kingdom. The Jacobites believed that this was an ideal opportunity for the Stewarts to be reinstated.

After the Jacobite Rising of 1715, General Wade, the general commander of Scotland, opened up the highlands with a network of roads and bridges, some of which are still preserved today. He reorganized the six independent highland companies from clan membership and let them control the highlands. These Black Watch , as the regiments were called, wore the dark blue and green pattern in their kilt that is still popular today .

In 1724 Wade estimated that around 22,000 men in the highlands could carry weapons. Of these, more than half would be willing to support another Stuart rebellion. According to these figures, the highland population at that time can very well be estimated at around 150,000. The government feared not so much the number of opposition activists, but rather the force that these clan men could develop in battle. Most feared was a preemptive strike by the highlands. This was based solely on the fact that momentum and onslaught, paired with the absolute ruthlessness both towards oneself and towards the enemy, paralyzed the enemy in fear. With the small shield on the left arm, a dagger in the left fist and the short broadsword in the right, the highlanders were able to penetrate far into the opposing troops and then divide into small units fighting under the leadership of their chief. This technique was much feared later - especially during the '45 uprising - so much that it was used again and again by Bonnie Prince Charlie as a kind of "secret weapon". The only time when a really significant number of clans cooperated was during the support of the Stewart dynasty in the 18th century.

The big exception in this time of the civil war - lowlands against large parts of the highlands - was the Campbell clan, who sided with the Hanoverians . The Catholic clans and many of the Protestant clans have always believed that the Stuart monarch was the chief of chiefs , although the Stuarts had never been particularly friendly towards the other clans. If they were ever interested in her at all, it was only when it came to making the highlands conform to the norms of the lowlands.

The time for the overthrow seemed well chosen - the British government was in financial distress and had an army of just 3,000 men, mostly recruits, under General John Cope.

On August 2nd, 1745, 30 years after the defeat of his father, the prince landed on Eriskay , an island in the Outer Hebrides , from France .

On his trip he had lost almost all material, only seven faithful with him and no more weapons or support. He came to a country that he hardly knew anything about and that he did not know. In the beginning, the Scottish Jacobites were reluctant to support Bonnie Prince Charlie. Because of the "king across the water", as his grandfather was romantically called, the clans had suffered greatly in the past.

The MacDonalds of Clanranald, MacDonalds of Sleat and MacLeods of Dunvegan - all refused to stand up for the prince. In spite of this, and in naive and complete trust in the legitimacy of his claim to the throne, Charles won the cunning Cameron of Lochiel at his side. On August 19, 1745, he hoisted his standard in Glenfinnan in front of around 1200 clan men. From then on, the highland clans formed his main support.

After 1745

After the last Jacobite revolt of 1745/46 and the Battle of Culloden , the highlands were destroyed and their courage was finally broken with the new disarmament law. In addition to the defeat, the highland culture, the social structure and the clan system were smashed with legal means. The Scottish lowlands were relieved to see the highland resistance eradicated.

Scotland was divided into two nations: one was commercially oriented and endeavored to adopt English customs, the other was agriculturally oriented, largely against its southern neighbors and made no secret of its Celtic temperament. The clans now only live in historical dimensions. At the time of their ultimate defeat, they had long been an economic and social anachronism from the perspective of the lowlands. But for the people of the highlands this abolition of the old order meant the tragic and irreversible loss of their own language and culture.

Military paths and roads had to be built by the government in the 18th century, and castles had to be besieged and occupied.

After the Battle of Culloden, many clan chiefs and families fled abroad. The consequences of the resulting redistribution of the lands to non-highlanders were the lack of interest of the new masters in the social structure of the respective local clans and instead the enforcement of their own economic interests; the proliferation of grazing by sheep on a large scale and the resulting expulsion of the rural population from large parts of the highlands in the notorious clearances .

The greatest problem was now the responsibility of the landlords for the people on their land. The old clan system had died, and even where the chiefs still owned the land, they could no longer feed the vastly increased population. The first country studies recorded 1,608,420 people in Scotland in 1801, but in 1831, just 30 years later, there were 2,364,386. That was an increase of almost 50% in such a short time. In the highlands the land quickly became scarce: 200,000 people lived on the not very productive soil of the highlands and could only poorly subsist on it. The remaining old clan chiefs and heads of families still felt responsible for the people living on their property and were thus in a bind.

New insights into land use and division were acquired from the continent and the Lowlands and implemented in the situation of the highlands. The little usable land could only properly feed a very thin population. So the simple inhabitants of the Scottish Highlands were once again among the losers. On the huge pastures, which were once bearable enough to fatten cattle and grow grain, the all-consuming sheep were soon kept, which brought the landlords quick and better profits.

The clan members were often forcibly evicted from their lease. The caretaker set fire to huts that were not voluntarily cleared, sometimes regardless of whether they were old or sick. In the course of the displacements , from which the highlands have not yet recovered, hundreds of thousands have been displaced and much of the highlands have literally been depopulated.

Some small farmers were given a small piece of land by their landlord in the coastal regions as compensation, but hardly any of the displaced farmers knew the sea or could handle a fishing boat; many perished. Tens of thousands emigrated to the continent or to Canada , America , New Zealand and Australia , or were resettled there with paid passage. What remained was what was once fertile homeland, at least in parts - today it is often deserted wasteland with a few overgrown foundation walls.

See also

literature

- The History of the Province of Moray . Edinburgh, William Auld, 1775.

- Robert Bain: The Clans and Tartans of Scotland. Collins, London / Glasgow 1938 (various reprints 1939–1984)

- Alexander Conrady: History of the Clan Constitution in the Scottish Highlands. Leipzig studies in the field of history 5.1; Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1898 ( digitized version )

- Hubert Gebele: The Scottish Clans in the 18th Century. About the change and end of a highland society on the edge of Europe. A Personal Passion Play in Scottish History and Bibliography, 2nd edition, Regensburg 2012 (comprehensive references up to 2012).

- Ian Grimble: Scottish Clans & Tartans . London 1984.