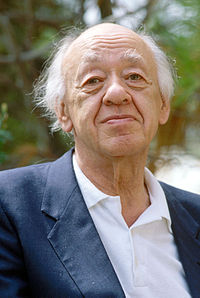

Eugène Ionesco

Eugène Ionesco ( ; born November 26, 1909 in Slatina , Romania as Eugen Ionescu; † March 28, 1994 in Paris ) was a Franco-Romanian author. He is considered the most important French playwright of the post-war period and a leading exponent of absurd theater . From the 1980s Ionesco also emerged as a painter.

Life and work

Childhood and youth

He was born in 1909 (and not, as is often found, in 1912) under the name Eugen Ionescu in what was then the Kingdom of Romania as the first child of a lawyer and administrative officer and the daughter of a French railway engineer who worked there. In 1913 the young family went to Paris because their father wanted to do a doctorate there . After Romania's entry into the war in August 1916, the father returned to his homeland, where he soon severed all ties to his family, applied for a divorce and married a second time.

Ionesco, now six, stayed in Paris with his younger sister and his mother, who laboriously supported themselves and the children with casual work and donations from their French relatives. He was placed in a children's home so that his mother could work, but he could not get used to it. From 1917 to 1919 he and his sister lived with a peasant family in a village, La Chapelle-Athenaise, near Laval (Mayenne) - in his memory a time of paradise.

In 1925 the siblings went to their father in Bucharest . Here, although they were born Romanian citizens, they had to learn Romanian almost like a foreign language and did not find a relationship with their stepmother (who remained childless). In 1926 Ionesco fell out with his apparently very authoritarian father, who had only contempt for the literary interests of his sixteen-year-old son, which had now become manifest, and wanted to turn him into an engineer.

Ionesco moved in with his mother, who had meanwhile come back to Romania and had found a decent post at the Romanian National Bank . In 1928 he began studying French at the University of Bucharest . Here he was a student of Nicolae C. Ionescu and came into contact with Emil Cioran and Mircea Eliade . He did not share their tendencies towards Nazism and Romanian fascism . He also met his future wife Rodica Burileanu, a philosophy and law student from an influential Romanian family. In addition, he read a lot and wrote (in Romanian ) poetry, columns and literary criticism . After graduating in 1934, he taught French in various schools and other educational institutions. In 1936 he married.

The years before, during and after World War II

In 1938, Ionesco obtained a doctoral scholarship for France through the Bucharest Institut Français , not least to avoid the pressure that weighed on left-wing intellectuals like him in increasingly totalitarian Romania. From Paris, which was decisive for all intellectual Romanians at the time, he supplied Romanian magazines with news from the Parisian literary scene.

After France's defeat by Germany in 1940, he and his wife went back to Romania, which was neutral and relatively calm at the time, where he was drafted as a soldier but not drafted.

In 1942 or 1943, after Romania joined Germany in the war against the Soviet Union in 1941 , the Ionescos managed to travel back to the now quieter France, where they stayed (first in Marseille , then in Paris ) for good. Their only child, daughter Marie-France, was born there in 1944. Financially they were doing bad, Ionesco worked as a galley proofs corrector in a Paris legal publishing house, where he remained employed until the 1955th

The slow climb

In 1948 Ionesco (initially still in Romanian) conceived his first piece, La Cantatrice chauve ( The Bald Singer ), which was performed in 1950 and, if not from the audience, at least received attention from a number of critics and writers. In 1950 he, whose mother tongue was French, took on French citizenship. He wrote the pieces La Leçon ( The Lesson , Performance 1951) and Jacques ou la Soumission (J. or Submission), which finally made him a French author.

In 1951 Les Chaises ( The Chairs ), Le Maître (The Teacher) and L'Avenir est dans les œufs (The future lies in the eggs) followed. In 1952 Victimes du devoir (sacrifice of duty) was created, at the same time La Cantatrice chauve and La Leçon were performed again.

1953 was a successful year: The Victimes were premiered, plus a series of seven sketches with success. A first anthology of pieces was printed. He also wrote Amédée ou comment s'en débarrasser (A. or How to get rid of him) and Le nouveau locataire (The new tenant).

After that he had established himself as an absurdly funny author who could almost make a living from his plays. In 1954 he wrote Le Tableau (Die Tafel) and the short story Oriflamme and made his first lecture tour abroad (to Heidelberg). In 1955 he wrote L'Impromptu de l'Alma (Das impromptu de l'Alma ) and saw the first performance of one of his pieces abroad ( Le nouveau locataire ). In 1957 La Cantatrice chauve and La Leçon were rehearsed by the small Parisian Théâtre de la Huchette , where they have been in the program without interruption until today (May 2019).

The years of success

In the autumn of 1957, the story Rhinocéros appeared , with which Ionesco reacted in a frightened manner to the epidemic outbreak of hurray patriotism and racism that attacked France during the " Battle of Algiers " (winter 1956/1957) with which France was inflamed by the media The military hoped to force a turning point in the Algerian War (1954–1962).

In the same year Ionesco received the honorary title Satrap of the quirky Collège de 'Pataphysique .

In the fall of 1958 the play Rhinocéros ( The Rhinos ) was created, which took over the plot and the person constellation of the story of the same name slightly changed and where Ionesco, apparently again frightened, reacted warningly to the "seizure of power" by General de Gaulle , many of whom are indeed different from him Supporters initially an authoritarian right-wing regime in the sense of z. B. Franco's hoped.

When the play, because it initially seemed too explosive for France, was premiered in Düsseldorf in 1959 , the German audience believed, however, that it was targeting National Socialism and its uncritical and all too willing followers - an interpretation that is only too popular in France took over when Rhinocéros was staged in 1960 in Paris, which was now quiet again. Ionesco himself later explained his play in the sense that it was not related to a specific ideology, but meant as a general critique of mass movements.

In the winter of 1958/1959 he developed the play Tueur sans gages (The murderer without payment) from his story La Photo du Colonel , which was premiered in Paris on February 19, 1959.

In 1961/1962 Le Roi se meurt (The King dies) was created, an encrypted swan song for France's ending role as a once proud colonial power . In 1962 he wrote Délire à deux (Delirium for two) and Le Piéton de l'air (Pedestrians of the Air; the latter in turn first as a story and only then as a play). Also in 1962, Ionesco published a collection of articles and lectures on his theater under the title Notes et contre-notes .

In 1964 there was another Ionesco premiere with La Soif et la faim (Hunger and Thirst). In the same year, Rhinocéros , a piece by him was performed for the first time in his native Romania.

The last few decades

Somewhat reluctantly, but unstoppable, Ionesco has now advanced to an established author who has been invited to give lectures, received prizes and honors, and in 1970 was also accepted into the Académie française . He finally tried his hand at the genre Roman and completed Le Solitaire (The Loner) in 1973 , where a kind of dropout and man without qualities recalls his meaningless past and present.

As a genuine playwright, he turned the novel into a play, Ce formidable bordel! (Such a mad house !, 1973), in which he lets the same man as the main character play a completely passive, almost mute and yet impressive role. Since he sarcastically mocked the 1968 “revolutionaries” en passant, he, who was once thoroughly leftist, was insulted by them as a fascist author.

In 1973 he received the Jerusalem Prize for the freedom of the individual in society .

In 1975 L'Homme aux valises (The Man with the Suitcases) came out and in 1980 his last play Voyages chez les morts (Journeys to the Dead). Thereafter, Ionesco retired to his position as the undisputed recognized author and enjoyed and administered his fame. He still wrote and published diligently, but in other genres, e.g. B. Autobiographical .

In the 1980s and 1990s he fell increasingly into severe depression and began painting as a therapy .

When Ionesco died in Paris at the age of 84 and was buried on the Cimetière Montparnasse , he was not only uncrowned king of the so-called "Theater of the Absurd", but was also considered one of the great French dramatists. The political messages that are often present in his plays are hardly noticed today, but rather understood as a criticism of all too human weaknesses. In the socially critical aspect of his work and in his pronounced linguistic humor, u. a. the influence of the Romanian writer Ion Luca Caragiale (1852–1912) can be seen. Ionesco wrote about him in Notes et contre-notes : "IL Caragiale is perhaps the greatest unknown dramatic author." Ionesco was also able to recognize himself in the personal fate of Caragiale, who had spent the last years of his life in voluntary exile in Berlin.

According to Le Monde of December 21, 2007, Ionesco was by far the most frequently performed French playwright outside of France.

In 1969 Ionesco was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

Personal exhibitions (selection)

- 1981: Erker-Galerie St. Gallen

- 1982: Studio d'Arte Contemporanea Dabbeni , Lugano

- 1982: Voyage chez les morts, Theater Basel

- February 17 to March 11, 1984: Kestnergesellschaft Hannover

- March 18 to April 17, 1984: Kommunale Galerie Berlin

- June 1 to July 7, 1984: Wallgraben Theater Freiburg

- May 17 to June 15, 1986: Saarland Museum Saarbrücken

List of works

Work edition

|

|

Dramas

|

Essays, diary

Poetry

Novels, short stories and short stories

Children's books

art

|

literature

To life and work

- Klaus Bahners: Eugène Ionesco: “The bald singer; The lesson; The rhinos ”. Interpretations. Königs Explanations and Materials , 392. C. Bange, Hollfeld 1997, ISBN 978-3-8044-1643-7

- François Bondy : Eugène Ionesco in self-testimonies and image documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1975, ISBN 3-499-50223-2

- Eugène Ionesco, Carl Albrecht Haenlein: Eugène Ionesco - Gouaches. Publisher The Society. 1984

- Alexandra Laignel-Lavastine: Cioran , Eliade , Ionesco. L'oubli du fascisme. Trois intellectuels dans la tourmente du siècle. Presses universitaires de France PUF, Paris 2002

- Carol Petersen: Eugène Ionesco . Colloquium, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-7678-0407-7

- Gert Pinkernell : Interpretations . Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 1992 (therein an interpretation of Rhinocéros as a politically motivated piece)

- Theo Rommerskirchen: Eugène Ionesco . In: viva signature si! Remagen-Rolandseck 2005, ISBN 3-926943-85-8

- Martin Esslin: The theater of the absurd from Beckett to Pinter . Hamburg 1965, ISBN 978-3-499-55684-5

Interviews and discussions

- Gero von Boehm : Eugène Ionesco. October 28, 1985 . Interview in: Encounters. Images of man from three decades . Collection Rolf Heyne, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-89910-443-1 , pp. 87-94

Web links

- Literature by and about Eugène Ionesco in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Eugène Ionesco in the German Digital Library

- Short biography and list of works of the Académie française (French)

- Eugène Ionesco in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Article "Ionesco" in the names, titles and dates of French literature , T.2 (main source for the biographical section "Life and Creation")

Individual evidence

- ↑ www.theatre-huchette.com , last accessed on June 15, 2019

- ↑ fatrazie.com: Histoire de Collège - Le 23. clinamen 84 (French, accessed on July 29, 2014)

- ^ Gallimard, Collection Idées, no 107, 1962, p. 117.

- ^ American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Book of Members ( PDF ). Retrieved April 18, 2016

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ionesco, Eugène |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ionescu, Eugen (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French playwright of Romanian origin, representative of the theater of the absurd |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 26, 1909 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Slatina , Romania |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 28, 1994 |

| Place of death | Paris |